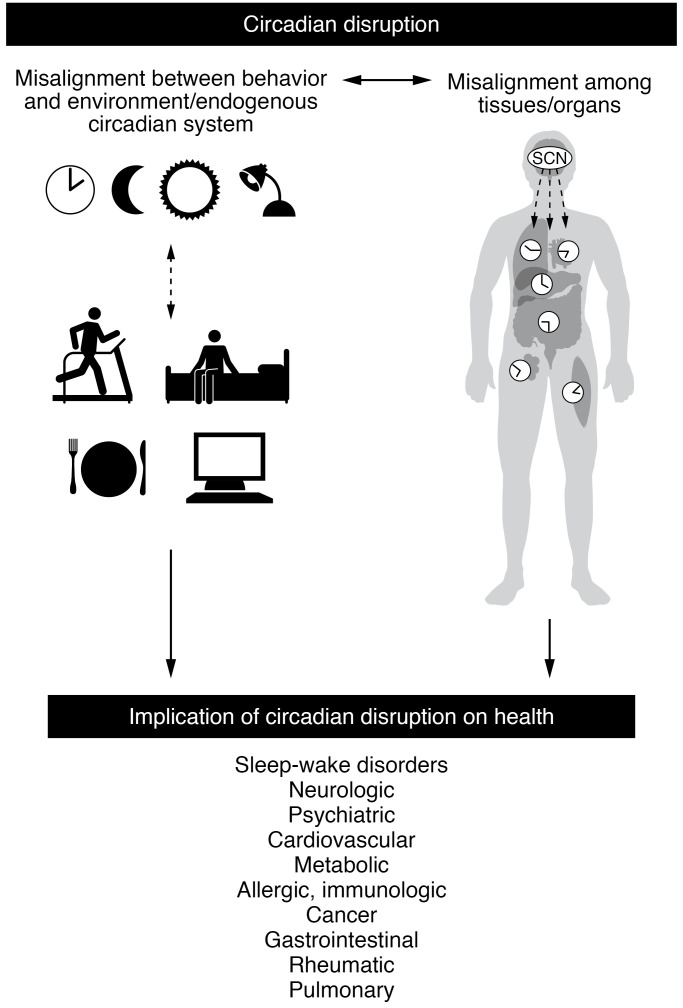

Figure 1. Schematic of the interrelationships between circadian disruption and human disease.

As depicted on the top left, circadian disruption can result from misalignment of external factors (such as the natural light/dark cycle, social and work requirements, and behaviors such as sleep and meal timing) with the master circadian clock located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), as well as with endogenous circadian clocks in other tissues. Common examples of chronic external-internal misalignment include social jet lag, shift work, and misalignment due to inappropriately timed light exposure (evening or night). The top right image depicts the SCN and the peripheral clocks throughout the body. The SCN integrates light and nonphotic stimuli to synchronize the timing of other brain and body clocks with the environment and behaviors. Disturbances at these various organizational levels result in circadian disruption. Disturbance in the phase and amplitude of circadian rhythms can occur at the molecular, cellular, and organismal levels. On the bottom are examples of the impact of circadian disruption and the bidirectionality between circadian disruption and the classical circadian sleep-wake disorders and other chronic medical disorders.