Abstract

Immunotherapy is a novel clinical approach that has shown clinical efficacy in multiple cancers. However, only a fraction of patients respond well to immunotherapy. Immuno-oncological studies have identified the type of tumors that are sensitive to immunotherapy, the so-called hot tumors, while unresponsive tumors, known as “cold tumors,” have the potential to turn into hot ones. Therefore, the mechanisms underlying cold tumor formation must be elucidated, and efforts should be made to turn cold tumors into hot tumors. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA modification affects the maturation and function of immune cells by controlling mRNA immunogenicity and innate immune components in the tumor microenvironment (TME), suggesting its predominant role in the development of tumors and its potential use as a target to improve cancer immunotherapy. In this review, we first describe the TME, cold and hot tumors, and m6A RNA modification. Then, we focus on the role of m6A RNA modification in cold tumor formation and regulation. Finally, we discuss the potential clinical implications and immunotherapeutic approaches of m6A RNA modification in cancer patients. In conclusion, m6A RNA modification is involved in cold tumor formation by regulating immunity, tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways, soluble inhibitory mediators in the TME, increasing metabolic competition, and affecting the tumor mutational burden. Furthermore, m6A RNA modification regulators may potentially be used as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for different types of cancer. In addition, targeting m6A RNA modification may sensitize cancers to immunotherapy, making it a promising immunotherapeutic approach for turning cold tumors into hot ones.

Keywords: N6-methyladenosine RNA modification, tumor microenvironment, cold tumors, hot tumors, biomarker, prognosis, immunotherapy

Introduction

Cancer currently ranks as one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and the latest reports indicate that the number of cancer patients is expected to rise by 70% in the next two decades (World Health Organization, 2014). Tumor development depends on the sophisticated tumor microenvironment (TME), which includes tumor, stromal, and immune cells as well as non-cellular components, such as vascular structure (Duan et al., 2020). Traditional chemoradiotherapy focuses on targeting tumor cells; in contrast, immunotherapy aims to activate immune cells and has emerged as an approach capable of achieving remarkable advances in cancer treatment (Lohmueller and Finn, 2017; Simone, 2020). Currently, immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), and the ligand PD-L1 have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Rotte, 2019; Aggen et al., 2020; Vaddepally et al., 2020). Furthermore, other kinds of immune checkpoint inhibitors are currently under investigation, such as lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), and V-domain Ig suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA) (Qin et al., 2019). Nevertheless, a large fraction of patients do not respond to immunotherapy. Importantly, studies exploring the TME have identified the kind of patients that are more sensitive to immunotherapy (Galon and Bruni, 2019). Briefly, depending on the response rates to immunotherapy, tumors are commonly divided into “hot tumors,” whose TME is characterized by the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and molecular signatures of immune activation, and “cold tumors,” whose TME is characterized by the absence of TILs and neoantigens (Galon et al., 2007; Camus et al., 2009; Van Allen et al., 2015; Gajewski et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2017). Consequently, numerous studies have aimed to turn cold tumors into hot ones (Rosenberg and Restifo, 2015; Sharma and Allison, 2015). For instance, recruitment of CD8+ T cells into cold tumors by rescuing interferon γ (IFN-γ) improves the immunopotentiating effect of dendritic cells (DCs) (Li X. et al., 2021). Several strategies have been proposed to turn cold tumors into hot tumors: enhancing inflammation in the TME of cold tumors, inhibiting the peritumoral immunosuppressive state, targeting aberrant tumor vasculature, attenuating tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways, and increasing TILs (Ochoa et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms whereby cold tumors are formed have yet to be determined.

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) modification, which was first discovered in the 1970s, has gained increasing attention for its important role in eukaryotic epigenetic regulation (Desrosiers et al., 1974; Huang et al., 2020a). Indeed, eukaryotic m6A messenger RNA (mRNA) modification is intimately related with almost all cellular and biological processes (Roignant and Soller, 2017). Recently, it was shown that m6A RNA modification has a close relationship with the immune response in the TME, suggesting its potential molecular role in the formation of cold tumors and use as a target to improve anticancer immunotherapy (Han D. et al., 2019). However, the researches focus on m6A RNA modification in tumor immunology is a novel frontier in cancer research, which not only reveals a new layer of epigenetic regulation in cancer by regulating immune response but can also lead to the development of effective novel therapeutics. In this review, we first describe the TME, cold and hot tumors, and m6A RNA modification. Then, we focus on the underlying mechanisms whereby m6A RNA modification may be implicated in cold tumor formation. Finally, we discuss the potential clinical implications of m6A RNA modification in cancer, and the immunotherapeutic strategies available for its targeting.

TME in Hot and Cold Tumors

Hot, Altered, and Cold Tumors

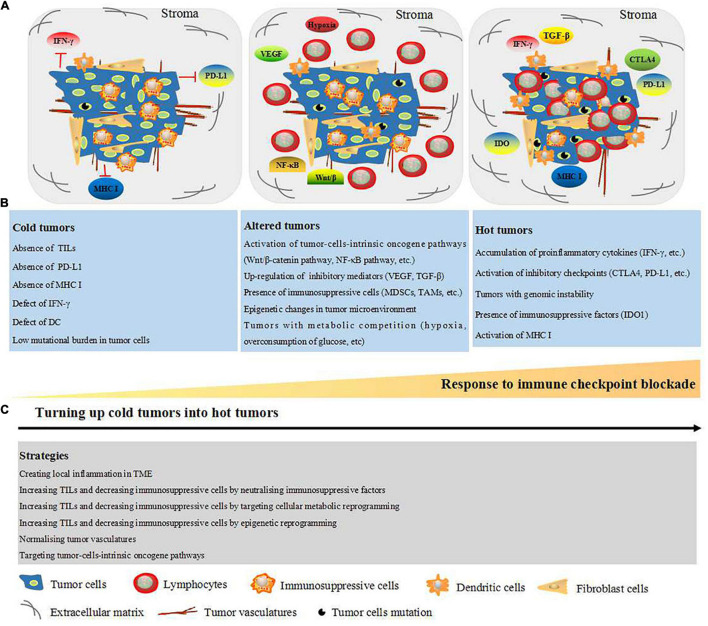

In 1863, Rudolf Virchow first observed that tumor tissues contain leukocytes, indicating an intimate correlation between inflammation and cancer (Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001). Over the past decades, studies involved in elucidating cancer-associated mechanisms have increased our understanding of the complex TME, which is composed of cellular and non-cellular components. The cellular components include fibroblasts and tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, and immunosuppressive and antitumor immune cells; extracellular matrix (ECM), oxygen, and metabolites constitute the non-cellular components (Binnewies et al., 2018). The composition of the TME explains why traditional chemoradiotherapeutic approaches directly targeting tumor cells are often non-effective. Immunotherapy is an emerging clinical therapeutic approach that focuses on targeting immune cells. It is worth noting that a wide range of tumor patients exhibit resistance to immunotherapy. It is generally accepted that the efficacy of immunotherapeutic approaches and prognosis depend on the density and diversity of immune cells within the tumor site (Fridman et al., 2012). Accordingly, tumors are classified into hot (highly infiltrated) and cold (non-infiltrated) tumors based on the presence and absence of TILs, respectively. Hot tumors appear to have an effective response to anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1, and anti-PD-L1 immunotherapies, while cold tumors do not respond to these immunotherapies (Gajewski, 2015). Hot tumors are characterized by high levels of TILs, accumulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, activation of inhibitory checkpoints (CTLA-4, PD-L1, etc.), genomic instability, presence of immunosuppressive factors such as indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), and the activation of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I). In contrast, cold tumors are characterized by poor lymphocyte infiltration inside the tumor and tumor stroma, absence of PD-L1, low mutational burden, and poor antigen presentation (loss of MHC I, IFN-γ defects, etc.) (Hegde et al., 2016). In 2009, Camus et al. (2009) described another type of tumors known as “altered tumors,” which contain stromal T cells, prevent T-cell infiltration inside of tumors, and present phenotypes that are between those of hot and cold tumors. Altered tumors are characterized by the activation of tumor-cell-intrinsic oncogene pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB); presence of tumor-soluble inhibitory mediators such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β); increased levels of immunosuppressive cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs); epigenetic changes in the TME; and metabolic competition (hypoxia, overconsumption of glucose, etc.) (Galon and Bruni, 2019). Both cold and altered tumors are derived from tumor-cell-intrinsic immunosuppression and impede effective antitumor immunity. Thus, in order for immunotherapies to have more impact, cold/altered tumors must be turned into hot tumors (Galon and Bruni, 2019; Ochoa et al., 2020).

Strategies to Turn Cold Tumors Into Hot Tumors

Based on the classification into hot, altered, and cold tumors, researchers have explored different strategies to turn cold tumors into hot tumors. For example, the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) is an attractive combination immunotherapeutic agent for tumor treatment by targeting TAMs (Mok et al., 2014; Cannarile et al., 2017; Razak et al., 2020). Furthermore, combined intratumoral interleukin (IL)-12 application with CTLA-4 was shown to lead to glioblastoma eradication through the elevation of CD4+ T-cell counts and Treg attenuation (Vom et al., 2013). As our understanding of cold and hot tumors expanded, strategies to turn cold tumors into hot tumors have been reported including creating local inflammation in the TME, increasing the levels of TILs, and decreasing levels of immunosuppressive cells by neutralizing immunosuppressive factors, targeting cellular metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming, normalizing tumor vasculature, and targeting tumor-cell-intrinsic oncogene pathways (Duan et al., 2020; Ochoa et al., 2020). An overview of the characteristics of hot, altered, and cold tumors as well as the strategies to turn cold tumors into hot ones is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of TME-dependent hot, altered, and cold tumors and strategies to turn up cold tumors into hot tumors. (A) TME consist of cellular components: tumor cells, fibroblast cells, DC, immunosuppressive cells [MDSCs, regulatory T cells (TAMs)], and lymphocyte (mainly T cell). Non-cellular components: tumor vasculature, ECM, oxygen, and metabolites. (B) Based on the TILs within the tumor site and response to immune checkpoint blockade, the tumors are classified into cold, altered, and cold tumors. Cold tumors are non-effective to immune checkpoint blockade and characterized with absence of TILs, PD-L1, MHC I, IFN-γ, and DC, which are all essential for neoantigen presentation. Furthermore, cold tumors are presented as low mutational burden in tumor cells. Altered tumors are represented with stromal T cells as well as the factors which prevent infiltration of T cells into the tumors, such as activation of tumor-cell-intrinsic oncogene pathways, upregulation of soluble inhibitory mediators (VEGF and TGF-β), and presence of immunosuppressive cells (MDSCs, TAMs, and regulator T cell). Moreover, epigenetic changes and metabolic competition (hypoxia and overconsumption of glucose) in tumor microenvironment are presented in the altered tumors. Hot tumors are represented with high degree of TILs and sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade. Additionally, hot tumors are characterized with accumulation of proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, etc.), inhibitory checkpoints (CTLA-4, PD-L1, etc.), IDO1, MHC I, and genomic instability (high tumors mutation burden). (C) Strategies to turn up cold tumors into hot tumors including creating local inflammation in TME, increasing TILs, and decreasing immunosuppressive cells by neutralizing immunosuppressive factors, targeting cellular metabolic reprogramming, targeting epigenetic reprogramming, targeting tumor-cell-intrinsic oncogene pathways, and normalizing tumor vasculature. CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; DC, dendritic cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; IDO1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; TME, tumor microenvironment; MDSCs, myeloid derived suppressor cells; MHC I, major histocompatibility complex class I; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophage; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

m6A RNA Modification

Discovery and Characteristics of m6A RNA Modification

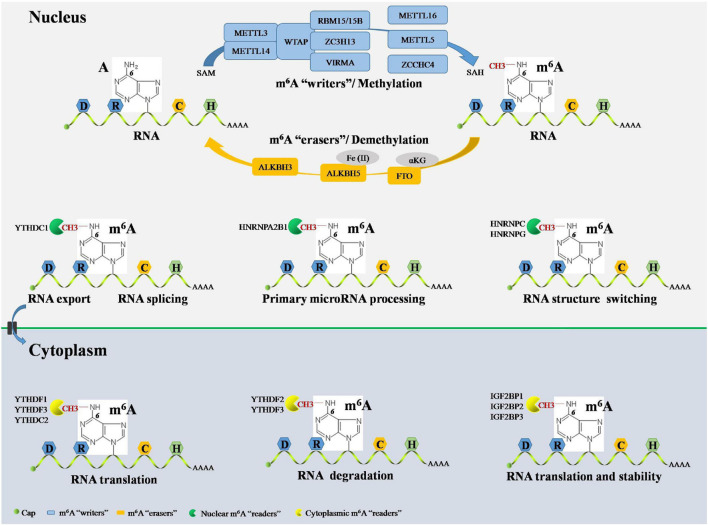

Epigenetic events are implicated in almost all major bioprocesses. These epigenetic events, which consist of DNA methylation, histone modification, and RNA-mediated processes, are reversible and dynamic chemical modifications (Ling and Ronn, 2019). These modifications are cooperatively interpreted by a multitude of guiding enzymes that can be classified into “writer,” “eraser,” and “reader” proteins. Disruption of any of these proteins contributes to disease development, including cancer (Dawson, 2017). DNA methylation and histone modification are essential for controlling chromatin remodeling and gene expression epigenetically. Nevertheless, the field of RNA-mediated processes has not moved forward very much (Deng et al., 2018; Jung et al., 2020). There is still a lot to uncover in terms of RNA-mediated processes, their regulation, and effects, etc., but more than 160 chemical RNA modifications have been identified since the 1950s, advancing our understanding of the biogenesis and function of RNA (Saletore et al., 2012). m6A, the methylation of adenosine (A) at the N6 position, was the first identified RNA modification and has been defined as the most widespread internal chemical modification in eukaryotic mRNA. Furthermore, m6A has also been identified in non-coding RNAs, such as ribosomal (rRNAs), small nuclear (snRNAs), small nucleolar (snoRNAs), micro- (microRNAs), long non-coding (lncRNAs), and circular (circRNAs) RNAs (Dominissini et al., 2012). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) studies have shown that m6A RNA modification sites in mRNA, microRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs are non-randomly distributed but have the DRACH consensus sequence (D = G/A/U; R = G/A; H = A/C/U; G/C/U: guanosine/cytidine/uridine) and are highly enriched in the coding sequence, 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR), and around stop codons (Meyer et al., 2012). Notably, the development of NGS-based approaches for m6A sequencing promises to delineate the landscape of the m6A epitranscriptome in various cellular contexts (Garcia-Campos et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020b). In line with DNA methylation and histone modification, m6A RNA modification is a reversible and dynamic process that can be installed, removed, and recognized by its writers, erasers, and readers, respectively (Wang et al., 2020d; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Overview RNA m6A modification by its “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers.” The RNA m6A have a consensus sequence DRACH sites and methylated A at the N6 position. In nucleus, m6A methylation in RNA can be installed by m6A writers complex, including METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, RBM15, RBM15B, and ZC3H13. RNA m6A methylation also can be installed by several writers independently, including METTL16, METTL5, and ZCCHC4. The initiate of RNA m6A modification is dependent on methyl donor SAM and terminate in SAH production. The RNA m6A can be reversibly and dynamically removed by m6A erasers in nucleus composed of FTO, ALKBH5, and ALKBH3. FTO-mediated RNA m6A demethylation is αKG dependent, and ALKBH5-mediated RNA m6A demethylation is Fe(II) dependent. The RNA m6A can be recognized by m6A readers both in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic m6A readers include YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, and YTHDC2. YTHDF1 and YTHDC2 promote RNA translation. YTHDF2 facilitates RNA degradation. YTHDF3 cooperates with YTHDF1 to promote RNA translation and synergy with YTHDF2 to facilitate RNA degradation. IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, and IGF2BP3 are essential for promoting the stability and translation of RNA. Nuclear m6A readers consist of YTHDC1, HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, and HNRNPG. YTHDC1 contributes to RNA splicing and RNA export from nucleus to cytoplasm. HNRNPA2B1 causes primary microRNA processing. HNRNPC and HNRNPG RNA end with structure switching. m6A, N6-methyladenosine; A, adenosine; C, cytidine; METTL, methyltransferase-like; WTAP, Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein; RBM, RNA-binding motif; ZC3H13, zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13; ZCCHC4, zinc finger CCHC-type containing 4; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosyl homocysteine; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; ALKBH, ALKB homolog; αKG, α-ketoglutarate; YTHDF, YT521-B homology domain-containing family; YTHDC, YT521-B homology domain-containing protein; IGF2BP, insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding protein; HNRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein.

m6A Writers

m6A writers install m6A through a methyltransferase complex (MTC) composed of several components. Methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL14, and Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein (WTAP) are core components of the m6A MTC (Bokar et al., 1997). METTL3 is the only catalytic subunit, which installs m6A by binding to the methyl donor, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), and transferring the methyl groups to adenine in the RNA molecule, producing S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH). METTL3 and METTL14 are co-localized in nuclear speckles and form METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer complexes in a 1:1 ratio. METTL14 also contains the catalytic donor; however, METTL14 itself is not a catalytic subunit but maintains METTL3 conformation and identifies catalytic substrates (Wang P. et al., 2016; Wang X. et al., 2016). Moreover, METTL14 cooperates with the histone mark, histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation (H3K36me3), to carry out m6A RNA methylation, suggesting a co-transcriptional mechanism underlying histone modification and RNA methylation in mammalian transcriptomes (Huang et al., 2019). WTAP does not have catalytic function but facilitates m6A deposition through recruitment of METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer complexes as well as localization to nuclear speckles (Ping et al., 2014). RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15) and RBM15B, which have no catalytic function, interacts with METTL3 and WTAP and assists these two core components to reach their target RNA sites for m6A RNA modification in nuclear speckles (Knuckles et al., 2018). Zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13) controls the MTC by binding to WTAP and is required for the nuclear localization of the ZC3H13-WTAP-Virilizer-Hakai complex, which is essential for facilitating m6A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency (Wen et al., 2018). Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA), also called KIAA1429, mediates preferential m6A mRNA methylation in the 3′-UTR and near stop codon (Yue et al., 2018). Furthermore, the MTC contains other components, such as METTL16 and METTL5. METTL16 has been suggested to function alone in catalyzing m6A modification on the U6 snRNA (Warda et al., 2017), whereas METTL5 acts as an independent RNA methyltransferase and is required for 18S rRNA m6A modification (Leismann et al., 2020). Moreover, zinc finger CCHC-type containing 4 (ZCCHC4) was identified as an RNA methyltransferase in 2019 and is essential for the independent methylation of 28S rRNA (Ma et al., 2019).

m6A Erasers

m6A RNA modification can be removed by a handful of specific demethylases known as erasers. The fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) was identified as the first m6A demethylase in 2011 (Jia et al., 2011). FTO is an α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent demethylase located in both the cell nucleus and cytoplasm (Gulati et al., 2014). FTO first oxidizes m6A to form N6-hydroxymethyladenosine (hm6A). Then, hm6A is converted to N6-formyladenosine (f6A). Lastly, f6A is converted to adenosine, thus removing the m6A RNA modification in the nucleus (Wang et al., 2020d). Furthermore, FTO also demethylates N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) in snRNA and N1-methyladenosine (m1A) in tRNA in the nucleus (Wei et al., 2018). It is worth mentioning that FTO can mediate mRNA and cap m6Am demethylation as well as tRNA m1A demethylation in the cytoplasm (Wei et al., 2018). Moreover, ALKB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) is another vital m6A eraser, which is Fe(II) dependent, locates in the nucleus, and seems to be an m6A-specific demethylase involved in m6A RNA modification (Zheng et al., 2013). Moreover, Ueda et al. (2017) recently identified ALKBH3, an m6A eraser suggested to be present in both, in the cytoplasm and nucleus, promoting the demethylation of target mammalian tRNA.

m6A Readers

The reversible processes of m6A RNA installation and removal occur through the alteration of the RNA structure. RNA-mediated biological functions are also regulated by m6A-binding proteins, which are called m6A readers (Li A. et al., 2017). On the one hand, cytoplasmic mRNA is decoded in the ribosome to produce a protein. On the other hand, messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) foci are essential for the storage or degradation of cytoplasmic RNA. The YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing proteins (YTHDFs) and insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs) play crucial roles in RNA-mediated biological functions by binding to m6A domains in the cytoplasm. YTHDFs include YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3. YTHDF1 selectively binds to m6A and recruits translation initiation factors, including the eukaryotic translation initiation factors (eIFs) 3/4E/4G, poly(A) binding protein (PABP), and 40S ribosomal subunit, to magnify RNA translation (Wang et al., 2015). The first identified m6A reader was YTHDF2, which recognizes m6A-modified RNA degradation sites via its C-terminal region and recruits the carbon catabolite repressor 4-negative on TATA (CCR4-NOT) deadenylase complex through its N-terminal region (Du et al., 2016; Zhang C. et al., 2020). YTHDF3 has overlapping roles in RNA fate through augmenting RNA translation in cooperation with YTHDF1 and promoting RNA degradation via synergy with YTHDF2 (Li A. et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017). Cytoplasmic IGF2BPs, including IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, and IGF2BP3, bind directly to m6A-modified RNA through its K homology domains and promote the stability and translation of RNA (Kataoka, 2019). Cytoplasmic YTH domain-containing protein 2 (YTHDC2) is another m6A reader that can recognize m6A and bind to meiosis-specific coiled-coil domain (MEIOC) and 5′-3′exoribonuclease 1, further increasing m6A-modified RNA translation (Hsu et al., 2017). Notably, m6A readers can also bind m6A in the nucleus. For example, YTHDC1 promotes exon inclusion in RNA by amplifying serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor 3 (SRSF3) or blocking serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor 10 (SRSF10) in the nucleus (Xiao et al., 2016). Furthermore, YTHDC1 plays a role in facilitating m6A-methylated RNA export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Roundtree et al., 2017). Additionally, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), including HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, and HNRNPG, recognize m6A and act as “m6A switches” that accelerate RNA and primary microRNA processing by changing the RNA structure (Alarcon et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2019).

In summary, studies have shown that m6A RNA modifications are implicated in a wide range of biological processes. Nevertheless, structural and biochemical data on m6A writers, erasers, and readers need to be further verified, and the detailed mechanisms regulated by these proteins remain undetermined. It is reasonable to believe that there are more m6A writer, eraser, and reader components, and that the mechanism underlying these protein-mediated RNA modifications will be elucidated with the development of quantification and sequencing methodologies (Bodi and Fray, 2017; Chen et al., 2019). A summary of the currently known m6A writers, erasers, and readers is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

The locations and mechanisms of RNA m6A modification regulators.

| Categories | Regulators | Locations | Mechanisms | References |

| m6A “writers” | METTL3 | Nucleus | The only catalytic subunit that installs m6A methylation by binding to SAM and producing SAH | Wang P. et al., 2016; Wang X. et al., 2016 |

| METTL14 | Nucleus | Forming METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer and steadies METTL3 conformation and identifies catalytic substrates; cooperates with the H3K36me3 to install RNA m6A methylation | Wang P. et al., 2016; Wang X. et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019 | |

| WTAP | Nucleus | Facilitating m6A deposition by recruiting METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer complex localization to nuclear speckles | Ping et al., 2014 | |

| RBM15/15B | Nucleus | Assisting METTL3 and WTAP to their target RNA sites for RNA m6A modification in nuclear speckles | Knuckles et al., 2018 | |

| ZC3H13 | Nucleus | Binding to WTAP and induces the nuclear localization of ZC3H13-WTAP-Virilizer-Hakai complex | Wen et al., 2018 | |

| VIRMA | Nucleus | Guiding region-selective mRNA m6A modification in 3′-UTR and near stop codon | Yue et al., 2018 | |

| METTL16 | Nucleus | Functioning alone in catalyzing m6A modification on U6 snRNA | Warda et al., 2017 | |

| METTL5 | Nucleus | Acting alone in catalyzing 18S rRNA m6A modification | Leismann et al., 2020 | |

| ZCCHC4 | Nucleus | Functioning alone in catalyzing 28S rRNA m6A modification | Ma et al., 2019 | |

| m6A “erasers” | FTO | Nucleus | Promoting m6A modification in RNA removed dependent on αKG; inducing RNA demethylation of m6Am in snRNA and m1A in tRNA | Gulati et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2018 |

| FTO | Cytoplasm | Promoting m6Am demethylation as well as tRNA m1A demethylation | Wei et al., 2018 | |

| ALKBH5 | Nucleus | Inducing m6A demethylation dependent on Fe (II) | Zheng et al., 2013 | |

| ALKBH3 | Nucleus/cytoplasm | Promoting demethylation of target mammalian tRNA | Ueda et al., 2017 | |

| m6A “readers” | YTHDF1 | Cytoplasm | Recruiting eIF3/4E/4G, PABP, and 40S ribosomal subunit to magnify RNA translation | Wang et al., 2015 |

| YTHDF2 | Cytoplasm | Recognizing m6A-modified RNA degradation sites by its C-terminal region, and recruiting carbon CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex by its N-terminal region | Du et al., 2016; Zhang C. et al., 2020 | |

| YTHDF3 | Cytoplasm | Increasing RNA translation in cooperation with YTHDF1 and promoting RNA degradation by synergy with YTHDF2 | Li A. et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017 | |

| IGF2BP1/ 2/ 3 | Cytoplasm | Promoting the stability and translation of RNA by binding to m6A-modified RNA through its K homology domains | Kataoka, 2019 | |

| YTHDC2 | Cytoplasm | Increasing m6A-modified RNA translation by binding to MEIOC and 5′-3′exoribonuclease 1 | Hsu et al., 2017 | |

| YTHDC1 | Nucleus | Promoting RNA splicing and facilitating m6A-methylated RNA exportation from nucleus to cytoplasm | Xiao et al., 2016; Roundtree et al., 2017 | |

| HNRNPA2B1 | Nucleus | Acting as “m6A switch” to accelerate primary microRNA processing | Alarcon et al., 2015 | |

| HNRNPC/ G | Nucleus | Acting as “m6A switch” to change the structure of RNA | Liu et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2019 |

Abbreviations: 3′-UTR: 3′ untranslated region; αKG: α-ketoglutarate; ALKBH: ALKB homolog; CCR4-NOT: carbon catabolite repressor 4-negative on TATA; eIF: eukaryotic translation initiation factor; FTO: fat mass and obesity-associated protein; H3K36me3: histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation; HNRNP: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; IGF2BP: insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding protein; m1A: N1-methyladenosine; m6A: N6-methyladenosine; m6Am: N6, 2′-O-dimethyladenosine; METTL: methyltransferase-like; MEIOC: meiosis-specific coiled-coil domain; PABP: poly(A) binding protein; PD-1: programmed death receptor 1; RBM: RNA-binding motif; rRNA: ribosomal RNAs; SAH: S-adenosyl homocysteine; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; SnRNA: small nuclear RNAs; tRNA: transfer RNA; VIRMA: vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated; WTAP: Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein; YTHDC: YTH domain-containing protein; YTHDF: YTH domain-containing family; ZC3H13: zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13; ZCCHC4: zinc finger CCHC-type containing 4.

Aberrant m6A RNA Modification in Cold Tumors

With the breakthrough in the field of m6A RNA modification research during the past decade, reversible and dynamic m6A RNA modifications have been reported in almost all normal physiological processes. Comprehensive studies have shown that the regulators of m6A RNA modification are systematically implicated in the formation of complex TMEs, affecting the immune microenvironment, tumor mutational burden, neoantigen load, immunotherapy response, and even survival (Zhang B. et al., 2020; He et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021b). Recently, studies have demonstrated that the aberration/imbalance of m6A RNA modification has a close relationship with immune disorders in cancer (Li H. B. et al., 2017; Su et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021). These findings suggest a role of m6A RNA modification in cold tumors.

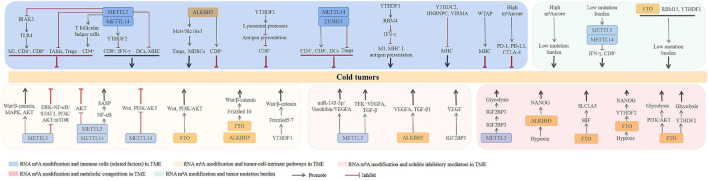

m6A RNA Modification and Immunity in the TME

In colorectal cancers with low mutational burden, which are resistant to immunotherapy, depletion of METTL3 and METTL14 increases the expression of CD8+ T cells and the secretion of IFN-γ via the m6A reader YTHDF2 (Wang et al., 2020b). Another study showed that tumors with decreased levels of METTL3 have increased DC infiltration, MHC expression, and levels of costimulatory and adhesion molecules in the TME (Shen et al., 2021a). On the contrary, loss of METTL3 has also been shown to promote tumor growth and metastasis. For example, METTL3-deficient mice show increased immunosuppressive cell (TAMs, Tregs) infiltration into tumors (Yin et al., 2021). Yao et al. (2021) showed that METTL3 is responsible for the expression of T follicular helper cells, which are specialized effector CD4+ T cells. Loss of METTL3 results in inactivation of T follicular helper cell differentiation by promoting the decay of T follicular helper cell signature genes, including Tcf7 transcripts. Using CRISPR-Cas9 screening, Tong et al. (2021) demonstrated that loss of METTL3 leads to the removal of m6A RNA modification on Irakm IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 3 (IRAK3) mRNA, slowing down its degradation and ultimately attenuating toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling-mediated macrophage activation. Particularly, the authors suggested that METTL3 augments the tumoricidal ability of macrophages by promoting the polarization bias of TAMs toward the M1 macrophage phenotype and rescuing infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Tong et al., 2021). Recently, mechanistic investigations found a positive role of ALKBH5 in Tregs and MDSCs by targeting Mct4/Slc16a3. Notably, low levels of ALKBH5 in clinical settings are correlated with low Treg cell numbers (Li et al., 2020c). However, another study by Tang et al. (2020) showed that deletion of ALKBH5 decreases the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Lysosomal proteases are responsible for antigen degradation in DCs (Cebrian et al., 2011). In a study by Han D. et al. (2019), YTHDF1 was shown to have a negative correlation with CD8+ T-cell infiltration in colon cancer patients. Mechanistically, YTHDF1 in DCs can recognize lysosomal proteases, leading to the inactivation of cross-presentation. Loss of YTHDF1 promotes DC-mediated cross-presentation of tumor antigens and cross-priming of CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo (Han D. et al., 2019). Additionally, other m6A RNA modification regulators have also been found to have a close relationship with immune cells in tumors. For instance, the expression of METTL14 and ZC3H13 is positively correlated with infiltrating levels of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and DCs, but negatively correlated with those of Tregs in breast cancer (Gong et al., 2020). In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, low expression of YTHDC2 is positively correlated with the low levels of B cells, CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, neutrophils, and infiltrating DCs (Li et al., 2020d). IFN-γ is the main proinflammatory cytokine produced by cytotoxic T cells, enhancing antigen presentation to cytotoxic T cells by facilitating MHC I and immunoproteasome expression in tumor cells (Cheon et al., 2014). YTHDF2 is responsible for RNA-binding motif 4 (RBM4)-mediated suppression of IFN-γ-induced M1 macrophage polarization and glycolysis (Huangfu et al., 2020). In a recent study by Shen et al. (2021a), downregulation of METTL3 was shown to contribute to increasing the levels of MHC molecules (Shen et al., 2021a). More recently, the levels of YTHDC2, HNRNPC, and VIRMA were suggested to be negatively correlated, whereas WTAP was positively correlated, with MHC molecules in endometrial cancer (Zhao et al., 2021). A comprehensive study showed that a low risk score of m6A signature is significantly correlated with a high expression of immune cell checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 (Mo et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the mechanisms whereby m6A RNA modification regulators exert their action in immune cells of the TME remain unclear.

m6A RNA Modification and Tumor-Cell-Intrinsic Pathways

Several studies have shown that METTL3 acts as an oncogenic regulator by activating tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways in tumors. For example, in hepatoblastoma, upregulation of METTL3 promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of hepatoblastoma cells by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Liu et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020). In colorectal cancer, METTL3 promotes tumor metastasis, stemness, and chemoresistance through activation of MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Peng et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2021b). Furthermore, METTL3 facilitates the proliferation and invasion of esophageal cancer cells via activation of Wnt/β-catenin and AKT signaling (Hou et al., 2020). In contrast, Yin et al. (2021) recently showed that ablation of METTL3 orchestrates tumor growth and metastasis by facilitating ERK-NF-κB/STAT3 signaling. Liu et al. (2018) showed that METTL14 mutation and loss of METTL3 expression contribute to increased proliferation and tumorigenicity of endometrial cancer cells by activating AKT signaling. Moreover, METTL3 knockdown in a multiplicity of tumor cell lines leads to the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling (Zhao et al., 2020). Wang Y. et al. (2021) indicated that METTL14 may be a favorable prognostic factor for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Mechanistically, loss of METTL14 increases gastric cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness by promoting the activation of Wnt and PI3K/AKT signaling. In contrast, knockdown of FTO restricts the activation of Wnt and PI3K/AKT signaling (Zhang et al., 2019). Recently, Liu et al. (2021a) showed that METTL3 and METTL14 are required for senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)-mediated tumor-promoting and immune-surveillance functions of senescent cells through the activation of NF-κB signaling. Frizzled proteins are key Wnt receptors whose activation contributes to the stabilization of cytoplasmic β-catenin (MacDonald and He, 2012). The activity of FTO and ALKBH5 lead to PARP inhibitor resistance in BRCA-deficient epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) cells by upregulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway through stabilization of Frizzled 10 protein (Fukumoto et al., 2019). YTHDF1 has been shown to promote stemness, tumor cell proliferation, and metastasis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway through the stabilization of Frizzled 5 and 7 (Bai et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Pi et al., 2021).

m6A RNA Modification and Soluble Inhibitory Mediators in the TME

As mentioned earlier, altered tumors are characterized by the presence of tumor angiogenesis. METTL3 has been shown to facilitate miR-143-3p biogenesis, promoting the brain metastasis in lung cancer patient samples through the miR-143-3p/Vasohibin/VEGFA axis (Wang et al., 2019). In line therewith, Wang G. et al. (2021) showed that METTL3 is responsible for the activation of tyrosine kinase endothelial (TEK)-VEGFA-mediated tumor progression and angiogenesis in bladder cancer. In colon cancer, the m6A RNA modification reader, IGF2BP3, can bind to the VEGF mRNA to promote its expression and stability. Thus, loss of IGF2BP3 restricts angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGF (Yang et al., 2020). Upregulation of TGF-β in the TME also contributes to altered tumor formation by suppressing T-cell proliferation and stimulating Treg development (Chen and Ten Dijke, 2016). In TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of lung cancer cell lines, the level of METTL3 was found to be upregulated. Loss of METTL3 attenuates TGF-β-induced morphological conversion of lung cancer cells, their cell migration potential, and EMT progression (Wanna-Udom et al., 2020). Mechanistic investigations found that METTL3 increases TGF-β1 mRNA decay and impairs TGF-β1 translation progress. Furthermore, ablation of METTL3 disrupts the autocrine action of TGF-β1 by interrupting TGF-β1 dimer formation and TGF-β1-induced EMT in cancer cells (Li et al., 2020a). Importantly, the level of VEGFA and content of TGF-β1 in the TME are decreased in ALKBH5-deficient melanoma cells (Li et al., 2020c).

m6A RNA Modification and Metabolic Competition in the TME

Recently, m6A RNA modification was recognized to be responsible for metabolic competition-mediated tumorigenesis. Cancer cells with metabolic competition contribute to tumorigenesis through inhibiting T-cell responses and increasing T-cell depletion (Kedia-Mehta and Finlay, 2019). Upregulation of ALKBH5 was shown to contribute to breast cancer initiation by attenuating NANOG mRNA methylation and thereby increasing NANOG expression under hypoxia (Zhang et al., 2016). FTO was found upregulated in tumor suppressor von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)-deficient ccRCC. Mechanistically, FTO increases metabolic reprogramming and survival of VHL-deficient ccRCC cells by targeting SLC1A5 in a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-independent way (Xiao et al., 2020). Furthermore, Niu et al. (2021) recently showed that the posttranscriptional regulation of the abnormal expression of aldolase A (ALDOA) under hypoxia was positively modulated by FTO-mediated m6A RNA modification in a YTHDF2-dependent manner in liver cancer cells, and hypoxia-mediated high level of ALDOA contributed to liver cancer development by promoting glycolysis metabolism and its terminal product lactate expression. Additionally, FTO promotes tumor cell glycolysis by activating PI3K/AKT signaling or in a YTHDF2-dependent manner (Liu et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021d). In addition, upregulation of METTL3 in gastric cancer promotes tumor angiogenesis and glycolysis by promoting IGF2BP3-dependent hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) mRNA stability, which is essential for increasing in glycolysis by activating GLUT4 and ENO2 in gastric cancer cells (Wang et al., 2020c).

m6A RNA Modification and Tumor Mutational Burden

Tumors with high mutational burden carry neoantigens that are sensitive to immune cells and immune checkpoint blockade (Samstein et al., 2019). Recently, numerous systematic and comprehensive studies have suggested a close relationship between m6A RNA modification and mutational burden. m6A RNA modification patterns are quantified as m6Ascore by a specific procedure (Zeng et al., 2019). Zhang B. et al. (2020) comprehensively investigated the m6A RNA modification patterns of 1,938 gastric cancer samples based on 21 m6A regulators and systematically analyzed the correlation between the m6Ascore and TME cell-infiltrating characteristics. They found that a low m6Ascore is markedly correlated with increased mutational burden and activation of immunity and correlated with increased neoantigen load and enhanced response to anti-PD-1/L1 treatment (Zhang B. et al., 2020). Another study showed a wide range of FTO, RBM15, and YTHDF1 inter-group expression differences between high- and low- tumor mutational burden cancer tissues (Liu et al., 2021c). Consistently, a recent study indicated that there is a positive correlation between the m6A signature and tumor mutational burden scores in 16 cancer types (Shen et al., 2021b). Furthermore, in colon cancer patients, a low m6Ascore is associated with high tumor mutational burden, PD-L1 expression, and mutation rates in significantly mutated genes (Chong et al., 2021). It is also noteworthy that colorectal cancers with low mutational burden were suggested to be resistant to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy through the inhibition of IFN-γ-mediated CD8+ T-cell secretion by METTL3 and METTL14 (Wang et al., 2020b). Nevertheless, the mechanisms whereby m6A RNA modification regulates the tumor mutational burden require further investigation.

Collectively, the mechanisms underlying m6A RNA modification-mediated cold tumor formation include immune cell regulation in the TME, targeting of tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways, facilitation of soluble inhibitory mediators in the TME, increase of metabolic competition in the TME, and effect on tumor mutational burden. Notably, several specific m6A regulators play dual roles in cold tumor formation, such as METTL3, METTL14, and YTHDF1, suggesting the exact role m6A RNA modification-mediated cold tumor formation is tumor-type dependent. Furthermore, the abnormal expression of m6A regulators contribute to cold tumor formation is not through one mechanism alone, they always play roles in cold tumor formation by several mechanisms. For example, METTL3 is involved in cold tumor formation via regulating immune cell expression, targeting of tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways, facilitating soluble inhibitory mediators, increasing metabolic competition, and affecting tumor mutational burden together, which indicated the extensive role of m6A RNA modification in cold tumor formation. In addition, some different m6A regulators are implicated in cold tumor formation by the same mechanism, such as METTL3 and ALKBH5, they both lead to cold tumor formation through VEGFA expression, indicating they may play a role in the cold tumor formation synergistically, which needs to be validated in the future. The studies involved in m6A RNA modification in cold tumor are just getting started; the related mechanism is still unclear and needs to be illustrated in the future. An overview of the uncovered mechanisms till now is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

The potential roles of RNA m6A modification in cold tumors. The mechanisms underlying RNA m6A modification-mediated cold tumors include regulating the immune cells in TME, targeting tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways, facilitating soluble inhibitory mediators in TME, increasing metabolic competition in TME, and affecting tumor mutation burden. ALKBH5, ALKB homolog 5; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DCs, dendritic cells; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; HNRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; M1, M1 macrophages; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; METTL, methyltransferase-like; MHC, major histocompatibility complex class; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; IFN-γ, interferon γ; IRAK3, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 3; IGF2BP, insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding protein; PD-1, programmed death receptor 1; PD-L1, programmed death receptor ligand 1; RBM, RNA-binding motif; SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TLR4, toll-like receptors 4; Tregs, regulatory T cells; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VIRMA, vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated; WTAP, Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein; YTHDC2, YT521-B homology domain-containing protein 2; YTHDFs, YT521-B homology domain-containing family; ZC3H13: zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13.

Potential Clinical Implications of m6A RNA Modification in Cancers

Considering the widespread role of m6A RNA modification in tumorigenesis, it is reasonable to assume that the expression of m6A writers, erasers, and readers might be used as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for cancer patients. Recent studies using Kaplan-Meier analysis and receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) have illustrated that METTL3 has potential clinical implications in cancer. For instance, compared with adjacent non-tumor tissues, METTL3 expression is upregulated in hepatoblastomas. High METTL3 levels are associated with continual recurrence and poor prognosis of hepatoblastoma patients, suggesting that METTL3 could be used as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for hepatoblastoma patients (Liu et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020). Furthermore, in bladder cancer, gastric cancer, and colorectal cancer, increased expression of METTL3 correlated with poor prognosis (Han J. et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020c). Since METTL3 plays overlapping roles in tumors (Zheng et al., 2019), its high expression was shown to be positively correlated with better survival in colorectal cancer (Deng et al., 2019). Compared with normal samples, the expression of METTL14 and ZC3H13 is decreased in invasive breast cancer stroma, invasive ductal breast cancer stroma, invasive mixed breast cancer, and ductal carcinoma in situ. These low levels of METTL14 and ZC3H13 are negatively correlated with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in luminal type A, luminal type B, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-enriched type, and triple-negative-type breast cancer, indicating that the reduced expression of METTL14 and ZC3H13 leads to poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (Gong et al., 2020). Additionally, overexpression of ALKBH5 is correlated with poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia patients (Shen et al., 2020). Upregulation of YTHDF1 is intimately associated with poor OS in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and gastric cancer patients (Liu et al., 2020; Pi et al., 2021). YTHDF2 is significantly overexpressed in hepatoblastoma and HCC when compared with their adjacent non-cancerous tissues, and overexpression of YTHDF2 is closely connected with poor prognostic clinical outcomes (Cui et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2020). Recently, Li et al. (2020d) showed that head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients with lower YTHDC2 levels have poorer OS and PFS than those with higher expression. Like METTL3, FTO also plays pro- and antitumor roles in cancer (Wang et al., 2020a). Cui et al. (2020) found that the upregulation of FTO in hepatoblastoma patients is correlated with poor clinical outcomes. However, Zhuang et al. (2019) suggested that low FTO expression is correlated with poor prognosis in endometrial cancer, lung cancer, rectum adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic cancer.

Furthermore, a genome metacohort analysis showed that low FTO and METTL14 levels and high METTL3, HNRNPA2B1, and YTHDF3 levels are correlated with poor prognosis in osteosarcoma patients (Li et al., 2020b). In endometrial cancer patients, higher HNRNPC, YTHDC2, WTAP, VIRMA, IGF2BP3, and HNRNPA2B1 expression is closely associated with worse outcomes and advanced stage (Zhao et al., 2021). Furthermore, high ALKBH5 levels in colon cancer indicates poor prognosis (Huang et al., 2021). In addition, numerous studies used the m6Ascore to investigate the potential clinical implications of m6A RNA modification patterns in cancer (Zhang B. et al., 2020; Du et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021a; Xu et al., 2021b). For example, Zhang C. et al. (2020) indicated that the m6Ascore can act as an independent prognostic biomarker in gastric cancer. In HCC patients, the OS of the low m6Ascore group was better than that of the high m6Ascore group (Shen et al., 2021a). Importantly, the OS of low-grade glioma patients who received chemotherapy was higher in the low-m6Ascore group than in the high-m6Ascore group (Du et al., 2021). These results suggest that m6A RNA modification has potential clinical implications in cancer patients, indicating their promising implications in improving cancer patient treatment outcomes. Nevertheless, the dual role of m6A RNA modification in cancers limited their clinical implications in cancers which needs to be solved in the future. Some of the significant studies examining the potential clinical implications of m6A RNA modification in cancers are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

The potential clinical implications of RNA m6A modification in cancers.

| Tumor types | Regulators | Expressions | Clinical implications | References |

| Hepatoblastoma | METTL3 | Up | High level of METTL3 is associated with continual recurrence and poor prognosis | Liu et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020 |

| Bladder cancer Gastric cancer Colorectal cancer | METTL3 | Up | Increased expression of METTL3 correlated with poor prognosis | Wang et al., 2020c; Liu et al., 2021b |

| Colorectal cancer | METTL3 | Up | High expression of METTL3 in colorectal cancer is positively correlated with better survival | Deng et al., 2019 |

| Osteosarcoma | METTL3 HNRNPA2B1 | Up | High level of METTL3 and HNRNPA2B1 are correlated with poor prognosis | Li et al., 2020b |

| Osteosarcoma | METTL14 | Down | Low level of METTL14 is correlated with poor prognosis | Li et al., 2020b |

| Breast cancer | METTL14 | Down | Low level of METTL14 is negatively correlated with the OS and RFS | Gong et al., 2020 |

| ccRCC | METTL14 | Down | High level of METTL14 exhibits as a favorable prognostic factor | Wang Y. et al., 2021 |

| Breast cancer | ZC3H13 | Down | Low levels of ZC3H13 is negatively correlated with the OS and PFS | Gong et al., 2020 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia Colon cancer | ALKBH5 | Up | Over-expressed ALKBH5 is correlates with poor prognosis | Shen et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2021 |

| HCC Gastric cancer | YTHDF1 | Up | Up-regulated YTHDF1 is associated with poor OS | Liu et al., 2020; Pi et al., 2021 |

| Hepatoblastoma HCC | YTHDF2 | Up | Over-expressed YTHDF2 is connection with poor prognostic clinical outcomes | Liu et al., 2019; Shao et al., 2020 |

| Osteosarcoma | YTHDF3 | Up | High level of YTHDF3 is correlated with poor prognosis | Li et al., 2020b |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | YTHDC2 | Down | Lower level of YTHDC2 indicates poorer OS and PFS | Li et al., 2020d |

| Endometrial cancer | YTHDC2 | Up | Higher expressions of YTHDC2 is closely associated with worse outcomes and advanced stage | Zhao et al., 2021 |

| Hepatoblastoma | FTO | Up | Up-regulated FTO is correlated with poor clinical outcomes | Liu et al., 2019 |

| Endometrial cancer Lung cancer Rectum adenocarcinoma Pancreatic cancer Osteosarcoma | FTO | Down | Low expression of FTO is correlated with poor prognosis | Zhuang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020b |

| Endometrial cancer | HNRNPA2B1 WTAP VIRMA IGF2BP3 HNRNPC | Up | Higher expressions of HNRNPA2B1, WTAP, VIRMA, IGF2BP3, and HNRNPC are closely associated with worse outcomes and advanced stage | Zhao et al., 2021 |

| Gastric cancer HCC | m6Ascore | Up | OS for the low m6Ascore group was better than the high m6Ascore group | He et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021a |

| Glioma | m6Ascore | Up | OS of low-grade glioma patients who received chemotherapy in the low-m6Ascore group is higher than those in the high-m6Ascore group | Du et al., 2021 |

Abbreviations: ALKBH: ALKB homolog; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; FTO: fat mass and obesity-associated protein; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HNRNP: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; IGF2BP: insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding protein; m6A: N6-methyladenosine; METTL: methyltransferase-like; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; VIRMA: vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated; WTAP: Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein; YTHDC: YTH domain-containing protein; YTHDF: YTH domain-containing family; ZC3H13: zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13.

Targeting m6A RNA Modification as Cancer Immunotherapy

The critical role of m6A RNA modification in the immune response in the TME and its confirmed clinical implications in cancer make m6A RNA modification an attractive immunotherapy in cancer. Studies have shown that lung adenocarcinomas and lung squamous cell carcinomas with lower expression of METTL3, RBM15, ALKBH5, YTHDC1, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, HNRNPC, and VIRMA are significantly more sensitive to immunotherapy and chemotherapy (Xu et al., 2020a,b). Furthermore, studies indicate that reversing the dysregulation of m6A RNA modification could promote the effectiveness of immunotherapy in cancer. For example, loss of METTL3 and METTL14 expression increases the response to anti-PD-1 treatment in colorectal cancer with low mutational burden (Wang et al., 2020b). Ablation of METTL3 expression in myeloid cell impairs anti-PD-1 therapeutic efficacy in B16 melanoma (Yin et al., 2021). Deletion of ALKBH5 can sensitize tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy, reduce tumor growth, and prolong mouse survival during GVAX/anti-PD-1 treatment by inhibiting the composition of tumor-infiltrating Tregs and MDSCs in vitro and in vivo, while melanoma patients harboring ALKBH5 deletion/mutation are more sensitive to anti-PD-1 therapy (Li et al., 2020c). Moreover, the therapeutic effect of anti-PD-L1 is elevated in YTHDF1-deficient mice, suggesting that YTHDF1 is a promising therapeutic target for immunotherapy in combination with checkpoint inhibitors (Han D. et al., 2019). The knockdown of FTO was shown to inhibit the metabolic barrier for CD8+ T-cell activation, promoted CD8+ T-cell infiltration in tumors, and synergized with anti-PD-L1 treatment (Samstein et al., 2019). In keeping with this, FTO knockdown sensitized melanoma cells to IFN-γ and anti-PD-1 treatment by increasing YTHDF2-dependent PD-1, CXCR4, and SOX10 RNA decay in mice (Yang et al., 2019).

Recently, it was suggested that quantification of the m6Ascore could predict the clinical response of cancer patients to immunotherapy. For instance, in colon cancer, Chong et al. (2021) found that cancers with a lower m6Ascore show better clinical responses to anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4, and anti-PD-L1 therapies. ccRCC patients receiving anti-PD-1, the low m6Ascore group presented an apparently prolonged survival (Zhong et al., 2021). Li H. et al. (2021) further validated that a low m6Ascore in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma patients indicates an inflammatory phenotype and higher sensitivity to anticancer immunotherapy. Zhou et al. (2021) also confirmed that m6Ascore-low pancreatic cancer patients have higher response rates to anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 treatments. Of note, an RNA modification writer score model was constructed by Chen et al. (2021) recently, which is based on differentially expressed genes responsible for RNA modification patterns and quantifies the RNA modification-related subtypes of individual tumors. The authors found that colorectal cancer patients with a low writer score in an anti-PD-L1 cohort presented significant clinical benefits and had a dramatically prolonged OS (Chen et al., 2021). Notably, we found that in some m6A regulators, such as YTHDF1 and YTHDF2, their lower expressions are both more sensitive to immunotherapy, suggesting a possible cooperative role in tumor immunotherapy, which needs to be explored in future studies. Some of the most important studies examining m6A RNA modification as a potential target for cancer immunotherapy are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Targeting RNA m6A modification as cancer immunotherapy.

| Tumor types | Regulators | Immunotherapy | References |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | METTL3 | Lower expressions of METTL3 is more sensitive to immunotherapy | Xu et al., 2020a |

| Low mutation burden of colorectal cancer | METTL3 METTL14 | Loss of METTL3 and METTL14 increase response to anti-PD-1 treatment | Wang et al., 2020b |

| Melanoma | METTL3 | Ablation of METTL3 in myeloid cells impairs anti-PD-1 therapeutic efficacy | Yin et al., 2021 |

| Melanoma Non-small cell lung cancer | FTO | Knockdown of FTO synergizes with anti-PD-L1 treatment | Samstein et al., 2019 |

| Melanoma | FTO | Knockdown of FTO sensitizes melanoma to anti-PD-1 | Yang et al., 2019 |

| Melanoma | ALKBH5 | Melanoma patients harboring ALKBH5 deletion/mutation are correlated with more sensitive to anti-PD-1 therapy | Li et al., 2020c |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | ALKBH5 RBM15 YTHDC1 YTHDF1 YTHDF2 | Lower expressions of ALKBH5, RBM15, YTHDC1, YTHDF1, and YTHDF2 are more sensitive to immunotherapy | Xu et al., 2020a |

| Melanoma Colon cancer | YTHDF1 | The therapeutic effect of anti-PD-L1 is elevated in YTHDF1 deficient mice | Han D. et al., 2019 |

| Lung squamous cell carcinoma | HNRNPC | Lower expressions of HNRNPC and VIRMA are more sensitive to immunotherapy and chemotherapy | Xu et al., 2020b |

| Colon cancer | m6Ascore | Lower m6Ascore showed a better clinical benefits to anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4, and anti-PD-L1 therapies | Chong et al., 2021 |

| ccRCC | m6Ascore | Low m6Ascore group presents a apparently prolonged survival in the anti-PD-1ccRCC patient | Zhong et al., 2021 |

| Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma | m6Ascore | Low m6Ascore indicates an inflammatory phenotype and more sensitive to anticancer immunotherapy | Li H. et al., 2021 |

| Pancreatic cancer | m6Ascore | m6Ascore-low pancreatic cancer patients have higher response rates to anti-PD-1and anti-CTLA-4 treatments | Zhou et al., 2021 |

| Colorectal cancer | “Writer” score | Low “writer” score present significant clinical benefits and have a dramatically prolonged OS in anti-PD-L1 cohort | Chen et al., 2021 |

Abbreviations: ALKBH: ALKB homolog; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4; FTO: fat mass and obesity-associated protein; HNRNP: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; m6A: N6-methyladenosine; METTL: methyltransferase-like; OS: overall survival; PD-1: programmed death receptor 1; PD-L1: programmed death receptor ligand 1; RBM: RNA-binding motif; VIRMA: vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated; YTHDC: YTH domain-containing protein; YTHDF: YTH domain-containing family.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Within the past decade, m6A RNA modification has been identified as a novel emerging layer of posttranscriptional regulation controlling gene expression in eukaryotes. Currently, it is clear that m6A RNA modification exhibits essential roles in almost all bioprocesses, including the immune response in cancers. In our present review, we have focused on discussing the underlying mechanisms whereby m6A RNA modification is implicated in cold tumor formation. We have also discussed the potential clinical implications and immunotherapeutic strategies of targeting m6A RNA modification in cancer. Indeed, m6A RNA modification is involved in cold tumor formation by regulating the immune cells in the TME, targeting tumor-cell-intrinsic pathways, facilitating the action of soluble inhibitory mediators in the TME, increasing metabolic competition in the TME, and affecting the tumor mutational burden. Furthermore, many m6A RNA modification regulators (m6A writers, erasers, and readers) have potential clinical applications as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for different types of cancer. In addition, targeting m6A RNA modification regulators could sensitize cancers to immunotherapy. Thus, targeting m6A RNA modification is a promising immunotherapeutic approach for turning cold tumors into hot ones.

Although tremendous progress has been achieved on understanding m6A RNA modification and their role in diseases, a complete understanding of the mechanisms is far away, and especially, their implications in cancers is our concern. The present researches show that the abnormal level of m6A regulators are intimately associated with the prognosis of tumors, indicating their promising implications in improving cancer patient treatment outcomes, although it has been demonstrated that targeting RNA m6A modification could be the optional combination therapy in cancer immunotherapy, the limitation is that except for the role of RNA m6A modification in immune response, their functions in tumor development should be taken into consideration, which could be a cause of immunotherapeutic resistance or insensitivity. For example, PD-1/PD-L1 acts as a tumor suppressor and mediates resistance to PD-1 blockade therapy in tumor (Wang et al., 2020e). Therefore, we believe that future research on m6A RNA modification should focus on several aspects. First, some specific m6A RNA modification regulators play opposite roles in different cancers, indicating that the exact role of m6A RNA modification regulators is cell or tissue dependent (Deng et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2020). Consequently, defining the context-specific role of m6A RNA modification regulators in cancers and their mechanisms will be crucial to direct specific m6A RNA modification regulator-based therapeutic interventions in the future. Second, we know that m6A RNA modification is found not only in mRNAs but also in non-coding RNAs, and that non-coding RNAs play critical roles in the immune response and immunotherapy in cancers (Atianand et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2020a); therefore, future studies focused on m6A-related non-coding RNAs in cancer will contribute toward the development of more effective and novel cancer immunotherapies (Chen et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021a). Third, studies evaluating the use of m6A RNA modification as cancer immunotherapy have mainly focused on regulating m6A RNA modification regulators through transfection experiments, which are difficult to translate to clinical trials or clinical practice; therefore, m6A RNA modification regulator agonists or antagonists should be searched in the future (Su et al., 2018). Lastly, considering the toxic side effects of cancer immunotherapy, target carrier material should be developed to carry immunotherapeutics including m6A modification RNA regulators that augment antitumor immune responses with reduced toxicity and side effects (Zeng et al., 2021).

Author Contributions

LZ and JuZ collected the data, finished the manuscript, and prepared the figures and tables. YC and BW gave constructive guidance. SZ, XL, JiZ, WW, YF, and SS participated in the design of this review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

- 3′ -UTR

3′ -untranslated region

- α KG

α-ketoglutarate

- A

adenosine

- ALDOA

abnormal expression of aldolase A

- ALKBH5

ALKB homolog 5

- C

cytidine

- CCR4-NOT

carbon catabolite repressor 4-negative on TATA

- circRNAs

circular RNAs

- CSF-1R

colony stimulating factor-1 receptor

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- DCs

dendritic cells

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- eIF

eukaryotic translation initiation factor

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- f6A

N6-formyladenosine

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FTO

fat mass and obesity-associated protein

- G

guanosine

- H3K36me3

histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HDGF

hepatoma-derived growth factor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- hm6A

N6-hydroxymethyladenosine

- HNRNP

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- IDO1

indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase 1

- IFN- γ

interferon γ

- IGF2BP

insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding protein

- IL

interleukin

- IRAK3

IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 3

- LAG-3

lymphocyte activation gene-3

- lncRNAs

long non-coding RNAs

- m1A

N1-methyladenosine

- m6A

N6-methyladenosine

- m6Am

N6 2′ -O-dimethyladenosine

- MDSCs

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MEIOC

meiosis-specific coiled-coil domain

- METTL

methyltransferase-like

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MHC I

major histocompatibility complex class I

- mRNP

messenger ribonucleoprotein

- MTC

methyltransferase complex

- NF- κ B

nuclear factor kappa-B

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- OS

overall survival

- PABP

poly(A) binding protein

- PD-1

programmed death receptor 1

- PD-L1

programmed death receptor ligand 1

- RBM 4

RNA-binding motif 4

- PFS

progression-free survival

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic curve

- rRNAs

ribosomal RNAs

- SAH

S-adenosyl homocysteine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- snRNAs

small nuclear RNAs

- snoRNAs

small nucleolar RNAs

- SRSF

splicing factor serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor

- TAMs

tumor-associated macrophages

- TEK

tyrosine kinase endothelial

- TGF- β

transforming growth factor- β

- TIGIT

T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain

- TILs

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TIM-3

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

- TLR4

toll-like receptors 4

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- U

uridine

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau

- VIRMA

vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated

- VISTA

V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation

- WTAP

Wilms’ tumor 1-associated protein

- YTH

YT521-B homology

- YTHDC2

YTH domain-containing protein 2

- YTHDFs

YTH domain-containing family

- ZC3H13

zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13

- ZCCHC4

zinc finger CCHC-type containing 4.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81802586 and 81871216), Research Fund of Anhui Institute of Translational Medicine (ZHYX2020A001), and Natural Science Foundation of Colleges and Universities (KJ2017A197).

References

- Aggen D. H., Drake C. G., Rini B. I. (2020). Targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 in metastatic kidney cancer: combination therapy in the first-line setting. Clin. Cancer Res. 26 2087–2095. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon C. R., Goodarzi H., Lee H., Liu X., Tavazoie S., Tavazoie S. F. (2015). HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m(6)A-Dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell 162 1299–1308. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atianand M. K., Caffrey D. R., Fitzgerald K. A. (2017). Immunobiology of long noncoding RNAs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35 177–198. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Yang C., Wu R., Huang L., Song S., Li W., et al. (2019). YTHDF1 regulates tumorigenicity and cancer stem cell-Like activity in human colorectal carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 9:332. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F., Mantovani A. (2001). Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357 539–545. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies M., Roberts E. W., Kersten K., Chan V., Fearon D. F., Merad M., et al. (2018). Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 24 541–550. 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodi Z., Fray R. G. (2017). Detection and quantification of n (6)-methyladenosine in messenger RNA by TLC. Methods Mol. Biol. 1562 79–87. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6807-7_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokar J. A., Shambaugh M. E., Polayes D., Matera A. G., Rottman F. M. (1997). Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA 3 1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus M., Tosolini M., Mlecnik B., Pages F., Kirilovsky A., Berger A., et al. (2009). Coordination of intratumoral immune reaction and human colorectal cancer recurrence. Cancer Res. 69 2685–2693. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannarile M. A., Weisser M., Jacob W., Jegg A. M., Ries C. H., Ruttinger D. (2017). Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors in cancer therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 5:53. 10.1186/s40425-017-0257-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebrian I., Visentin G., Blanchard N., Jouve M., Bobard A., Moita C., et al. (2011). Sec22b regulates phagosomal maturation and antigen crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell 147 1355–1368. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Yao J., Bao R., Dong Y., Zhang T., Du Y., et al. (2021). Cross-talk of four types of RNA modification writers defines tumor microenvironment and pharmacogenomic landscape in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 20:29. 10.1186/s12943-021-01322-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wei Z., Zhang Q., Wu X., Rong R., Lu Z., et al. (2019). WHISTLE: a high-accuracy map of the human N6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome predicted using a machine learning approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:e41. 10.1093/nar/gkz074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Ten Dijke P. (2016). Immunoregulation by members of the TGFbeta superfamily. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16 723–740. 10.1038/nri.2016.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Lin Y., Shu Y., He J., Gao W. (2020). Interaction between N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) modification and noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol. Cancer 19:94. 10.1186/s12943-020-01207-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon H., Borden E. C., Stark G. R. (2014). Interferons and their stimulated genes in the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Oncol. 41 156–173. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong W., Shang L., Liu J., Fang Z., Du F., Wu H., et al. (2021). M(6)A regulator-based methylation modification patterns characterized by distinct tumor microenvironment immune profiles in colon cancer. Theranostics 11 2201–2217. 10.7150/thno.52717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., Wang Z., Li J., Zhu J., Ren Z., Zhang D., et al. (2020). Cross talk between RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase-like 3 and miR-186 regulates hepatoblastoma progression through Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway. Cell Prolif. 53:e12768. 10.1111/cpr.12768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. A. (2017). The cancer epigenome: concepts, challenges, and therapeutic opportunities. Science 355 1147–1152. 10.1126/science.aam7304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng R., Cheng Y., Ye S., Zhang J., Huang R., Li P., et al. (2019). M(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 suppresses colorectal cancer proliferation and migration through p38/ERK pathways. Onco Targets Ther. 12 4391–4402. 10.2147/OTT.S201052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Su R., Weng H., Huang H., Li Z., Chen J. (2018). RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 28 507–517. 10.1038/s41422-018-0034-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers R., Friderici K., Rottman F. (1974). Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71 3971–3975. 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., et al. (2012). Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485 201–206. 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Zhao Y., He J., Zhang Y., Xi H., Liu M., et al. (2016). YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 7:12626. 10.1038/ncomms12626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Ji H., Ma S., Jin J., Mi S., Hou K., et al. (2021). M6A regulator-mediated methylation modification patterns and characteristics of immunity and stemness in low-grade glioma. Brief. Bioinform. bbab013. 10.1093/bib/bbab013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q., Zhang H., Zheng J., Zhang L. (2020). Turning cold into hot: firing up the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cancer 6 605–618. 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman W. H., Pages F., Sautes-Fridman C., Galon J. (2012). The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 298–306. 10.1038/nrc3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto T., Zhu H., Nacarelli T., Karakashev S., Fatkhutdinov N., Wu S., et al. (2019). N(6)-Methylation of adenosine of FZD10 mRNA contributes to PARP inhibitor resistance. Cancer Res. 79 2812–2820. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski T. F. (2015). The next hurdle in cancer immunotherapy: overcoming the non-T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment. Semin. Oncol. 42 663–671. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski T. F., Corrales L., Williams J., Horton B., Sivan A., Spranger S. (2017). Cancer immunotherapy targets based on understanding the T cell-inflamed versus non-T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1036 19–31. 10.1007/978-3-319-67577-0_2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J., Bruni D. (2019). Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18 197–218. 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J., Fridman W. H., Pages F. (2007). The adaptive immunologic microenvironment in colorectal cancer: a novel perspective. Cancer Res. 67 1883–1886. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Campos M. A., Edelheit S., Toth U., Safra M., Shachar R., Viukov S., et al. (2019). Deciphering the “m(6)A Code” via antibody-independent quantitative profiling. Cell 178 731–747. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong P. J., Shao Y. C., Yang Y., Song W. J., He X., Zeng Y. F., et al. (2020). Analysis of N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase reveals METTL14 and ZC3H13 as tumor suppressor genes in breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 10:578963. 10.3389/fonc.2020.578963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati P., Avezov E., Ma M., Antrobus R., Lehner P., O’Rahilly S., et al. (2014). Fat mass and obesity-related (FTO) shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Biosci. Rep. 34:e00144. 10.1042/BSR20140111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B., Yan S., Wei S., Xiang J., Liu K., Chen Z., et al. (2020). YTHDF1-mediated translation amplifies Wnt-driven intestinal stemness. EMBO Rep. 21:e49229. 10.15252/embr.201949229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D., Liu J., Chen C., Dong L., Liu Y., Chang R., et al. (2019). Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m(6)A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature 566 270–274. 10.1038/s41586-019-0916-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Wang J. Z., Yang X., Yu H., Zhou R., Lu H. C., et al. (2019). METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol. Cancer 18:110. 10.1186/s12943-019-1036-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Tan L., Ni J., Shen G. (2021). Expression pattern of m(6)A regulators is significantly correlated with malignancy and antitumor immune response of breast cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 28 188–196. 10.1038/s41417-020-00208-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde P. S., Karanikas V., Evers S. (2016). The where, the when, and the how of immune monitoring for cancer immunotherapies in the era of checkpoint inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 22 1865–1874. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou H., Zhao H., Yu X., Cong P., Zhou Y., Jiang Y., et al. (2020). METTL3 promotes the proliferation and invasion of esophageal cancer cells partly through AKT signaling pathway. Pathol. Res. Pract. 216:153087. 10.1016/j.prp.2020.153087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. J., Zhu Y., Ma H., Guo Y., Shi X., Liu Y., et al. (2017). Ythdc2 is an N(6)-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 27 1115–1127. 10.1038/cr.2017.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A. C., Postow M. A., Orlowski R. J., Mick R., Bengsch B., Manne S., et al. (2017). T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 545 60–65. 10.1038/nature22079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Weng H., Chen J. (2020a). M(6)A modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: Roles and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cancer Cell 37, 270–288. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Weng H., Chen J. (2020b). The biogenesis and precise control of RNA m(6)A methylation. Trends Genet. 36 44–52. 10.1016/j.tig.2019.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Weng H., Zhou K., Wu T., Zhao B. S., Sun M., et al. (2019). Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m(6)A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature 567 414–419. 10.1038/s41586-019-1016-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Zhu J., Kong W., Li P., Zhu S. (2021). Expression and prognostic characteristics of m6A RNA methylation regulators in colon cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:2134. 10.3390/ijms22042134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]