Abstract

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia has emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen. Treatment of S. maltophilia infections is difficult due to increasing resistance to multiple antibacterial agents. In this 12-month cross-sectional study, from 2017 to 2018, 117 isolates were obtained from different clinical sources and identified by conventional biochemical methods. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed according to CLSI 2018. Minocycline disk (30 μg) and E-test strips for ceftazidime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and chloramphenicol were used. PCR confirmed isolates. The frequency of different classes of integrons (I, II) and resistance gene cassettes (sul1,sul2, dfrA1, dfrA5 and aadB) were determined by PCR. The results showed the highest frequency of resistance to chloramphenicol and ceftazidime with 32 cases (27.11%). Among strains, 12 cases (10.25%) were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (the lowest frequency of resistance), while 19 (16.1%) isolates were resistant to minocycline. Frequency of sul1, int1, aadB, sul2, dfrA5 genes were 64 (55.08%), 26 (22.3 %), 18 (15.25%) and 17 (14.4%), 14 (11.86%), respectively. int2 and dfrA1 were not detected. Although we have not yet reached a high level of resistance to effective antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, as these resistances can be carried by a plasmid, greater precision should be given to the administration of these antibiotics.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance genes; gene cassette, integrons; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Introduction

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is the third cause of nosocomial infections caused by nonfermented gram-negative bacilli. S. maltophilia is the most important genus of Stenotrophomonas that belongs to group V of the Pseudomonas family (16S rRNA based) [[1], [2], [3]]. This bacterium is colonized in toilets, water coolers, medical equipment, respiratory tract patients, intravascular catheters and ulcers [3,4]. This organism has emerged as an important opportunistic pathogen in humans worldwide. Although it has inadequate pathogenicity, S. maltophilia causes various types of hospital-acquired and community-acquired infections [1]. These bacterium’s diseases include endocarditis, wound infections, cellulitis, bacteremia, urinary tract infections, pneumonia and rarely meningitis [5,6]. Chronic pulmonary disease, immunodeficiency, history of overuse or inadequate antibiotic use, long hospital or ICU history, renal failure, prolonged diarrhoea, transplant rejection and catheterization are the most critical risk factors for infections [6]. Treatment of S. maltophilia infections is difficult due to increasing resistance to multiple antibacterial agents [7]. During the past years, S. maltophilia has been known as one of the principal multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms in hospital settings due to displaying high levels of acquired resistance and intrinsic to a broad array of antibacterial agents, including most common of β-lactam antibiotics, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. One of the important mechanisms in transferring resistance genes is an element called integron [12]. Integrons are conserved DNA sequences, which can efficiently acquire and transfer the resistant genes among bacteria and are usually located on mobile genetics elements [12]. It is important to identify these resistance genes [12,13]. Class I and subsequently, class 2 integrons are the most common classes of clinical isolates. Class 1 integrons carry more than 40 resistance genes associated with resistance to aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, macrolides, sulfonamides and disinfectants [13,14]. The low resistance of S. maltophilia to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) has led to its use in therapy. Unfortunately, with a rise in acquired resistance to this antibiotic, the management of S. maltophilia infections has become increasingly difficult. The sul genes have been found to relate to SXT resistance and interact with class 1 integron elements. In addition, dfrA genes in the class 1 integron gene cassettes have been shown to cause significant resistance to SXT [15]. The aadB gene cassette promotes resistance to aminoglycosides and is associated with class 1 integrons [16]. Given the importance of S. maltophilia as a multidrug-resistant opportunistic pathogen, investigating the role of various intrinsic and acquired factors in developing drug resistance is important [14].

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to determine the antibiotic resistance profile and the frequency of integron types and aadB, dfrA1, dfrA5, sul1, sul2 genes in S. maltophilia isolated from clinical specimens of patients admitted to several teaching hospitals in Tehran.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates

This study was performed from 2017 to 2018 as a cross-sectional study in three major teaching hospitals (Dr Ali Shariati, Imam Khomeini and Naft hospitals) in Tehran, Iran. This project was approved by the Iran University of Medical Sciences Ethics committee (Ethical code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC 1396.7973).

Various clinical specimens of hospitalized patients with suspected infections, such as urine, blood, respiratory secretions, etc., were collected based on the physician’s diagnosis and sent to the laboratory. According to standard instructions, the specimens were cultured on blood agar, MacConkey agar and chocolate agar and incubated for 24–72 hours at 37 ° C. Nonfermenter gram-negative rods suspected of S. maltophilia were identified by phenotypic methods such as fermentation reaction in TSI medium, oxidative consumption of sugars in OF medium, oxidase test, esculin hydrolysis, citrate consumption, lysine consumption and nitrate reduction.

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used to control mediums and other procedures.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The fresh culture was used to prepare the bacterial suspension for antimicrobial susceptibility on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) (all media from Merck, Germany). 0.5-McFarland standard was used to compare the bacterial suspension’s turbidity to achieve appropriate density to evaluate the effect of antimicrobial agents. Minocycline disk (30μg) was used to determine antibiotic susceptibility by disk diffusion method. ≤ 14 mm zone diameter for minocycline disk (30μg) considered resistant by the CLSI [7]. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ceftazidime and chloramphenicol for each isolate were determined by the E-test (Liofilchem, Italy) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline [7]. Isolates with MIC for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole ≤ 2/38 μg/mL, ceftazidime ≤8 μg/mL, chloramphenicol ≤8 μg/mL were characterized as susceptible isolates and isolates with MIC for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole ≥ 4/76 μg/mL, ceftazidime ≥32 μg/mL, chloramphenicol ≥32 μg/mL considered resistant. The isolates were stored at –80 °C for further tests.

DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The method used for genomic DNA extraction was boiling. For evaluating the extracted DNA’s quality, the concentration and relative uptake of A260/A280 in each isolate were determined by the Biophotometer apparatus (Thermo Scientific, USA). Then, DNA was electrophoresed on 0.7% agarose gel stained with Gel Red ™ (Biotium, Landing Pkwy, Fremont, CA, USA) in TBE buffer (0.5 ×) (Tris/Boric acid/EDTA) and the presence of DNA bands in the U.V. transilluminator were investigated.

Specific primers for the chitinase A gene were used to confirm the isolates. The presence of class 1, 2 integrons, sul1, sul2, dfrA1, dfrA5 and aadB genes in each isolate were evaluated using the primers presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

PCR primers

| Primer | Sequence | Target | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| int1-R | AAGCAGACTTGACCTGA | Class 1 Integron | [20] |

| int1-F | GGCATCCAAGCAGCAAG | ||

| hep51 | GATGCCATCGCAAGTACGAG | Class 2 Integron | [23] |

| hep74 | CGGGATCCCGGACGGCATGCAC | ||

| chiA - R | ACGCCGGTCCAGCCGCGCCCGTA | Chitinase A | [24] |

| chiA - F | CATCGACATCGACTGGGAATACCC | ||

| dfrA1- R | TTGTGAAACTATCACTAATGGTAG | dfrA1 | [20] |

| dfrA1- F | CTTGTTAACCCTTTTGCCAGA | ||

| dfrA5- R | TCCACACATACCCTGGTCCG | dfrA5 | [20] |

| dfrA5 - F | ATCGTCGATATATGGAGCGTA | ||

| Sul1 - R | ATTCAGAATGCCGAACACCG | sul1 | [20] |

| Sul1 - F | TAGCGAGGGCTTTACTAAGC | ||

| Sul2- R | GAAGCGCAGCCGCAATTCAT | sul2 | [20] |

| Sul2 - F | CCTGTTTCGTCCGACACAGA | ||

| aadB - R | AGGTTGAGGTCTTGCGT | aadB | [25] |

| aadB - F | CCGCAGCTAGAATTTTG |

Conditions of PCR cycling were set up as follows: 5 min at 95 °C as initial denaturation, 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 60 sec, annealing (the temperature depended on the primer sequence), extension at 72 °C for 50 sec and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min on a T100™ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels within TBE buffer (0.5x) (Tris/Boric acid/EDTA). DNA bands were detected by staining with Gel Red ™ (Biotium, Landing Pkwy, Fremont, CA, USA) and imaged under U.V. illumination. Some PCR products were purified and submitted for sequencing (Bioneer Co., South Korea), The sequences were checked by Chromas software, and the fastA sequences were compared using online BLAST software (https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/BLAST/).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze the results wherever needed.

Results

In this study, the highest S. maltophilia was observed in blood in 108 cases (92.3%) and the least in the wound (0.85%). The highest frequency was in the emergency ward and the least in the operating room ward and the general surgery and surgical ward (Chart 1, Chart 2).

Chart 1.

The frequency of S. maltophilia strains collected from different specimens.

Chart 2.

The frequency of S. maltophilia strains collected from different wards of the hospitals.

From 117 S. maltophilia, 58 (49.57%) isolates were obtained from males, and 59 (50.42%) isolates from females.

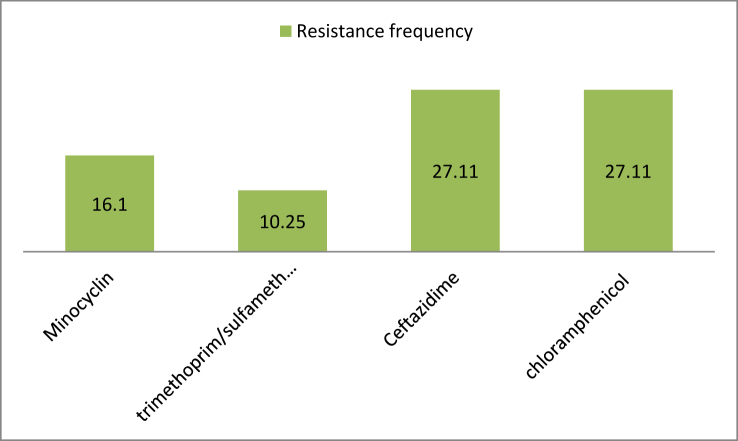

The antibiotic susceptibility test results showed the highest and the lowest frequency of resistance to chloramphenicol and ceftazidime were 32 cases (27.11%) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 12 cases (10.25%), respectively (Chart 3).

Chart 3.

Antibiotic resistance profile of S. maltophilia isolates (%).

In this study, all strains were examined for the presence of sul1, sul2, aadB, dfrA1, dfrA5, int1 and int2 genes. The most common resistance genes were sul1 and int1, respectively. The gene for class 1 integrons was detected in 26 (22.03%) of the 117 S. maltophilia isolates, and no class 2 integron gene was found. 55.08% (64 cases) carrying the sul1 gene. Frequency of aadB gene in S.maltophilia isolates was 18 (15.25%), while sul2 gene frequency was 17 (14.40%) and dfrA5 gene frequency 14 (11.86%). Interestingly, no dfrA1 gene was found in any of the isolates(Chart 4).

Chart 4.

The number of detected genes per specimen type.

Discussion

The extensive use of antibiotics that are widely used has contributed to resistance [17]. Transfer of class 1 integron-mediated antibiotic resistance genes has been widely stated in bacterial isolates from specific geographic regions. S. maltophilia is a species intrinsically obtaining an array of resistance elements; therefore, the influence of class 1 integron on the antimicrobial agent resistance should be more problematic than we can imagine [18]. It has been well-known that S. maltophilia acquires many chromosomal aminoglycoside resistance genes such as multidrug efflux pumps and aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs) genes [2,5,8,18]. The chromosome of S. maltophilia acquires many antimicrobial resistance genes, but few are involved in the SXT resistance reported so far [1,5,8]. In our study, class 1 integrase (intI) was detected in 26 (22.03%) of the 117 S. maltophilia isolates, and no class 2 integron was found. Inconsistent with our study, Huang et al. demonstrated a high prevalence of class 1 integron in the SXT-resistant isolates, which agrees with the previous studies. Also, Huang et al. reported that the most important significance of class 1 integron’s horizontal gaining should be related to SXT resistance in S.maltophilia [18]. In our study, most strains of S. maltophilia were susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Therefore, this antibiotic is still the best drug with a favourable antimicrobial effect in treating nosocomial infections caused by S. maltophilia strains. In another research in Iran, Nikpour et al. in Jahrom demonstrate that isolate had a high level of susceptibility to chloramphenicol (90.7%) and co-trimoxazole [19]. A similar study in China by Li-Fen Hu et al. showed that the rate of resistance to co-trimoxazole was 30.4%, and 64.7% of the isolates had class 1 integron. None of the co-trimoxazole susceptible strains had sul2 and dfrA genes. However, the sul1 gene was found in 27 co-trimoxazole-sensitive strains and 25 co-trimoxazole-resistant strains [20]. Contrary to this study, Sandra Abril Herrera-Heredia et al. conducted a study to evaluate the risk factors and mechanisms associated with resistance to SXT in S. maltophilia infections in Mexico in 2017. Resistance to ciprofloxacin (26%), co-trimoxazole (26%), chloramphenicol (14.3%) and levofloxacin (2.6%) were reported. There is no relationship between SXT resistances with sul genes. Due to the high resistance to SXT, it is not an effective treatment for patients; instead, levofloxacin can be used as an appropriate treatment option against S. maltophilia infection [21]. Our study’s finding demonstrates that 55.08% (64 cases) carry the sul1 gene. Koichi Tanimoto examined in Japan, reported that most strains were resistant to ciprofloxacin (84.8%), tetracycline (97%) and chloramphenicol (78.8%), although levofloxacin was effective against (77.3%) of the strains. SXT resistance is mediated by sul and dfrA genes, particularly class I integrons [22]. Some evidence has shown cross-transmission. It indicates the cross-transmission of antibiotic-resistant strains to the hospital and shows the need for effective control and prevention measures in hospitals.

Despite co-trimoxazole resistance genes in many of the strains (55.08%), some isolates did not demonstrate resistance to SXT in vitro.

According to the results, the finding of co-trimoxazole resistance genes in hospital centres, and the high level of intrinsic resistance, it is necessary to discuss the control and prevention of transmission of these strains and handwashing programs. In discussing the use of antibiotics effectively on this strain, although we have not yet reached a high level of resistance to effective antibiotics such as co-trimoxazole, as the plasmid carries this resistance, greater precision should be given to the administration of these antibiotics.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate a high prevalence of MDR among S.maltophilia isolates in Tehran hospital centres. A high prevalence of class I integron and the associated determinants, particularly sul1 and aadB, present in MDR strains isolated from hospitalized patients. Statistical analysis shows the relation of MDR isolates and integron class I, which needs continuous surveillance in health care centres, in this opportunistic pathogen. The main question is why the resistant genes are not express in some isolates. Many isolates carry co-trimoxazole resistance genes, which means that there is a potential risk of increased antibiotic resistance in ambush, which is of concern.

Credit author statement

Zohre Baseri and Shabnam Razavi conceived and designed the study. Zohre Baseri, Amin Dehghan, Sajad Yaghoubi, and Shabnam Razavi contributed to comprehensive research. Sajad Yaghoubi and Amin Dehghan wrote the paper. Amin Dehghan, Zohre Baseri, participated in manuscript editing. Zohre Baseri and Shabnam Razavi have done practical work.

Author contribution

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. They played an active role in drafting the article or revising it critically to achieve important intellectual content, gave the final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Transparency declaration

All of the authors declare that there are no commercial, personal, political any other potentially conflicting interests related to the submitted manuscript. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement

We want to thank the ‘Department of Microbiology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran’ for their kind cooperation.

References

- 1.Adegoke A.A., Stenström T.A., Okoh A.I. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as an emerging ubiquitous pathogen: looking beyond contemporary antibiotic therapy. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2276. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alqahtani J.M. Emergence of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia nosocomial isolates in a Saudi children’s hospital: risk factors and clinical characteristics. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(5):521–527. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.5.16375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooke J.S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(1):2–41. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyot A., Turton J.F., Garner D. Outbreak of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia on an intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2013;85(4):303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crum N.F., Utz G.C., Wallace M.R. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(12):925–927. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000026977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senol E. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: the significance and role as a nosocomial pathogen. J Hosp Infect. 2004;57(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 28th ed.. CLSI supplement M100.

- 8.Gajdács M., Urbán E. Epidemiological trends and resistance associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia: a 10-year retrospective cohort study in a tertiary-care hospital in Hungary. Diseases. 2019;7(2):41. doi: 10.3390/diseases7020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson L., Esterly J., Jensen A.O., Postelnick M., Aguirre A., McLaughlin M. Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim versus fluoroquinolones for the treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bloodstream infections. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;12:104–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nys C., Cherabuddi K., Venugopalan V., Klinker K.P. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients with monomicrobial Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(11):e00788–e00819. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00788-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko J.H., Kang C.I., Cornejo-Juárez P., Yeh K.M., Wang C.H., Cho S.Y. Fluoroquinolones versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(5):546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akrami F., Rajabnia M., Pournajaf A. Resistance integrons; A mini review. Caspian J Intern Med. 2019;10(4):370–376. doi: 10.22088/cjim.10.4.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorestani R.C., Akya A., Elahi A., Hamzavi Y. Gene cassettes of class I integron-associated with antimicrobial resistance in isolates of Citrobacter spp. with multidrug resistance. Iran J Microbiol. 2018;10(1):22–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bostanghadiri N., Ghalavand Z., Fallah F., Yadegar A., Ardebili A., Tarashi S. Characterization of phenotypic and genotypic diversity of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strains isolated from selected hospitals in Iran. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1191. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung H.S., Kim K., Hong S.S., Hong S.G., Lee K., Chong Y. The sul1 gene in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia with high-level resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35(2):246–249. doi: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones L.A., McIver C.J., Kim M.J., Rawlinson W.D., White P.A. The aadB gene cassette is associated with bla SHV genes in Klebsiella species producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(2):794–797. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.794-797.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehrabi M., Salehi B., Rassi H., Dehghan A. Evaluating the antibiotic resistance and frequency of adhesion markers among Escherichia coli isolated from type 2 diabetes patients with urinary tract infection and its association with common polymorphism of mannose-binding lectin gene. New Microbe. New Infect. 2020;38:100827. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y.W., Hu R.M., Lin Y.T., Huang H.H., Yang T.C. The contribution of class 1 integron to antimicrobial resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Microb Drug Resist. 2015;21(1):90–96. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikpour A., Shabani M., Kazemi A., Mohandesi M., Ershadpour R., Rezaei Yazdi H. Identification and determination of antibiotic resistance pattern of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolated form medical devices and clinical samples in jahrom hospitals by phenotype and molecular methods. Jmj. 2016;14(2):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu L.F., Chang X., Ye Y., Wang Z.X., Shao Y.B., Shi W. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole mediated by acquisition of sul and dfrA genes in a plasmid-mediated class 1 integron. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37(3):230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez-Noriega E., Paláu-Davila L., Maldonado-Garza H.J., Flores-Treviño S. Risk factors and molecular mechanisms associated with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in Mexico. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(8):1102–1109. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanimoto K. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strains isolated from a university hospital in Japan: genomic variability and antibiotic resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62(4):565–570. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.051151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu L.F., Chen G.S., Kong Q.X., Gao L.P., Chen X., Ye Y. Increase in the prevalence of resistance determinants to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in clinical Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates in China. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jankiewicz U., Brzezinska M.S., Saks E. Identification and characterization of a chitinase of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, a bacterium that is antagonistic towards fungal phytopathogens. J Biosci Bioeng. 2012;113(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plante I., Centrón D., Roy P.H. An integron cassette encoding erythromycin esterase, ere (A), from Providencia stuartii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(4):787–790. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]