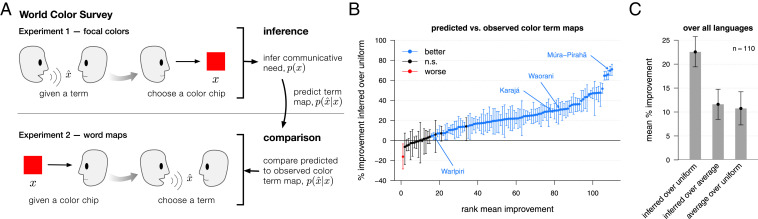

Fig. 3.

Inference and prediction within the WCS. (A) WCS (2) included two separate experiments with native speakers of each language. In this study, we used only the WCS focal color experiment to infer the communicative needs of colors, , and to predict a language’s mapping from colors to terms, . Without any additional fitting, we then compared the predicted term maps to the empirical term maps observed in the second WCS experiment. (B) Predicted term maps tend to agree with the observed term maps (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Moreover, the predicted term maps show better agreement with the empirical data than would predictions assuming a uniform distribution of communicative needs. Shown are the rank ordered mean percentage improvement in predicted versus observed term maps using the inferred communicative need compared to a uniform communicative need, with 95% CIs (bootstrap resampling; see Measuring Distance between Distributions over Colors). Languages (points) colored black have 95% CIs overlapping 0%; blue indicates significant improvement. Languages that do worse under the inferred distribution of needs (red points) violate model assumptions. (C) Over all languages, the mean percentage improvement (and 95% CIs) in predicted vocabularies when using language-specific commutative needs compared to uniform needs (“inferred over uniform”), language-specific versus average needs over all languages (“inferred over average”), and average versus uniform needs (“average over uniform”). Some improvement in predictive accuracy is attributable to commonalities in communicative needs across languages (third comparison), and yet more improvement is attributable to variation in needs among languages (second comparison).