Abstract

Dynamic phosphorus MRS (31P-MRS) is a method used for in vivo studies of skeletal muscle energetics including measurements of phosphocreatine (PCr) resynthesis rate during recovery of submaximal exercise. However, the molecular events associated with the PCr resynthesis rate are still under debate. We assessed vastus lateralis PCr resynthesis rate from 31P-MRS spectra collected from healthy adults as part of the CALERIE II study (caloric restriction) and assessed associations between PCr resynthesis and muscle mitochondrial signature transcripts and proteins (NAMPT, NQO1, PGC-1α, and SIRT1). Regression analysis indicated that higher concentration of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) protein, a mitochondrial capacity marker, was associated with faster PCr resynthesis. However, PCr resynthesis was not associated with greater physical fitness (VO2 peak) or messenger ribonucleic acid levels of mitochondrial function markers such as NQO1, PGC-1α, and SIRT1, suggesting that the impact of these molecular signatures on PCr resynthesis may be minimal in the context of an acute exercise bout. Together, these findings suggest that 31P-MRS based PCr resynthesis may represent a valid non-invasive surrogate marker of mitochondrial NAMPT in human skeletal muscle.

Keywords: 31P-MRS, mitochondria, muscle, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

INTRODUCTION

Phosphorus MRS (31P-MRS) provides in vivo non-invasive measurements of skeletal muscle function in humans.1 Parametric 31P-MRS measurements reflecting the recovery time constant of phosphocreatine (PCr), also referred to as the PCr resynthesis rate, have been of interest in exercise science because they reflect mitochondrial capacity or maximum adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis via coupled creatine kinase reactions in skeletal muscle. These parametric measurements have shown physiological relevance in assessments of the skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity and/or function in athletes, sedentary individuals, and individuals with Type 2 diabetes2 under normoxic, hypoxic, or exercise conditions.3–7 Specifically, PCr resynthesis rate has been shown to decrease from endurance-trained athletes to lean sedentary individuals to obese sedentary subjects to individuals with Type 2 diabetes mellitus.2 In addition, exercise training can shorten the PCr resynthesis rate of sedentary individuals8 and enhancements in PCr resynthesis rate are associated with enhancements of insulin sensitivity.9,10 Together these findings have made skeletal muscle 31P-MRS based PCr resynthesis rate a promising biomarker for studies of skeletal muscle biochemistry.

However, the biological mechanisms underlying 31P-MRS based PCr resynthesis rate during recovery of submaximal muscle contraction are not fully understood. During exercise, PCr undergoes breakdown to maintain ATP concentration constant in the face of ATP hydrolysis, and the rate of replenishment is driven by several putative physiological and molecular factors. Muscle oxygen availability is one such factor: in exercise trained individuals, fractional inspired oxygen during plantar flexion modulates PCr resynthesis rate under normoxic and hypoxic conditions,7,11,12 although in untrained individuals only fairly severe hypoxia influences PCr resynthesis rate.6 PCr resynthesis rate is influenced by molecular factors as well. For example, greater ATPmax (maximum ATP resynthesis rate (mM/L) for measuring maximum phosphorylation capacity: a 31P-MRS readout closely related to PCr resynthesis rate) has been shown to be associated with greater nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) protein level in skeletal muscle in a combined sample of athletes and individuals with Type 2 diabetes or obesity before and after a 3-week exercise intervention.13 However, it is not clear whether this correlation still holds within any sub-group of this combined sample, or whether it holds in sedentary individuals who have not undergone exercise training. Recently, relationships between PCr resynthesis rate and molecular signatures of mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle (NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α), and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)) have been postulated, but not confirmed.14,15

We examined relationships between PCr resynthesis rate and protein or messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels of multiple mitochondrial genes (NAMPT, NQO1, PGC-1α, and SIRT1) in individuals enrolled in a clinical trial. We hypothesized that, because NAMPT protein is a key component of human skeletal muscle, which facilitates the fast recovery of PCr when it is depleted, greater NAMPT protein levels would be associated with faster PCr resynthesis rate.

2 |. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1 |. Study participants

The present study included 10 men and 18 women, ages 20–50 years, with body mass index (BMI) from 22 to 27.9 kg/m2 at the screening visit, all part of the CALERIE II study (clinical trials registration NCT00427193, NCT02695511) for investigating mitochondrial dysfunction with aging in metabolically healthy humans. The study was approved by the institutional review board (PBRC − 26039) at Pennington Biomedical Research Center and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to the study. This retrospective analysis involved 28 healthy participants measured at baseline for maximum oxygen intake (VO2 peak) during a cardiopulmonary fitness test, PCr resynthesis rate by 31P-MRS, and mRNA or proteins from muscle biopsies.

2.2 |. Cardiopulmonary fitness

Assessment of cardiopulmonary fitness was performed on a programmable treadmill (Trackmaster® TmX425C, CareFusion, Newton, KS). Participants were fitted with a flexible respiratory mask and gases were continuously measured with an integrated metabolic measurement system (Parvo Medics TrueOne® 2400, Sandy, UT). The test began with a walk at a zero-inclined level for 2 min, and gradually increased at a rate of 1_/min until the participant became exhausted. Weighted oxygen intake as VO2 peak was measured in mL/min/kg during the last two minutes of exercise.

2.3 |. MRS data acquisition and quantification

All magnetic resonance experiments were performed on a GE 3 T Signa HDxt scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). A single loop 31P-tuned surface coil, 6 cm in diameter, was used to acquire 31P-MRS data using a simple pulse and acquire sequence with non-selective excitation. Prior to the 31P-MRS measurements, a single shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) imaging sequence was acquired via the scanner’s body coil to determine the anatomical location of the vastus lateralis muscle and 31P surface coil (using a vitamin E pill as a phantom at the center of the 31P surface coil for localization). Magnetic field shimming was performed on muscle by monitoring the 127.73 MHz signal from the muscle water and fat protons. The position of the vastus lateralis muscle was well within the limit of depth of penetration of the surface coil. A (28 mM) 31P-labeled creatine phosphate phantom placed on the top of the surface coil was used for 31P RF calibration through transmit gain adjustment by nullifying/minimizing the signal for a reference 180° hard pulse. Two different 31P-MRS datasets were acquired: baseline and exercise. In a baseline dataset, a spectrum was acquired (repetition time (TR) 15 s, 16 time averages per spectra, 5 kHz spectral bandwidth,16 4096 points, nonselective RF pulse with nominal 90° flip angle; see Figure S1). The purpose of acquisition of the baseline spectrum is to obtain a high-fidelity estimate of the baseline PCr concentration prior to exercise. This high-fidelity estimate allowed us to determine whether the PCr concentration had fully recovered to the baseline value after exercise. Subsequently for the exercise dataset, a series of 75 partially saturated spectra were acquired (TR = 1.5 s, four dummy scans, four time averages per spectrum, 5 kHz spectral bandwidth,16 4096 points, non-selective RF excitation with nominal 90° flip angle). During exercise 31P-MRS dataset acquisition, the participant was instructed to begin isometric leg-kicking exercise13 against tight and rigid Velcro straps, during which sequential MRS spectra were collected. The relative height of the PCr peak was monitored in real time, and the participant was instructed to stop kicking when the PCr peak height was reduced to 40 ± 10% of baseline. This range has shown to provide adequate PCr depletion while maintaining physiological pH. However, we validated the pH levels by calculating the chemical shift differences between the Pi and PCr peaks in the time series data. This 31P-MRS pH measurement makes use of the fact that basic and acidic species of Pi are in rapid exchange at physiological pH.17 The post-processing of spectra was executed with jMRUI Version 5.218 and quantitation of metabolite peaks was performed in the time domain with the AMARES (Advanced Method for Accurate, Robust, and Efficient Spectral fitting) algorithm.19 Confirmed PCr resonance peak data was transferred into MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and fitted with a mono-exponential equation,

| (1) |

using a non-linear least squares method. P(t), the PCr peak at each moment in time t, is expressed as a function of the recovery time parameter (τ) and scaling parameters (P(0) and D). The parameter P(0) represents the PCr level at the end of exercise (ie the beginning of PCr recovery), whereas D is the difference between the PCr levels at the end of exercise and at the end of recovery. P(0), D, and τ are free parameters whose values are estimated from each 31P-MRS scan.

2.4 |. Human muscle tissue biopsy

The muscle biopsy was completed on the leg that was not used to collect 31P-MRS data. Participants provided approximately 600 mg of muscle using the Bergstrom technique20 in the vastus lateralis. Briefly, the skin surface area was disinfected with 7.5% povidone-iodine prep solution (Aplicare, Forest Hills, NY). A topical anesthesia was induced with a mixture of 2% lidocaine HCl (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) and 0.5% bupivacaine HCl (AUROMEDICS Pharma, Dayton, NJ) to produce local anesthetic effects at the location of muscle biopsy. A 0.75 cm incision was made into the skeletal muscle fascia, fascia fibers were teased apart with the blunt edge of the scalpel, the Bergstrom needle was inserted to remove muscle tissue, and the wound was closed using bandage. The tissue was further processed for mRNA and protein extractions.

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software Version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We studied the relationship between τ and a set of molecular mitochondrial signatures (NAMPT protein and mRNA levels of PGC-1α, NAMPT, SIRT1, and NQO1) as well as VO2 peak. We hypothesized that VO2 peak and the mitochondrial signatures would be associated with τ. To perform this analysis, we took an incremental model building approach to understand both the independent and joint effects of mitochondrial signatures on τ. Specifically, we implemented the regression model shown in Equation 2 to relate a dependent variable y to independent variables x1, …, xk:

| (2) |

where the dependent variable yi is the ith subject’s τ, α is the intercept of the regression line, βj is the regression coefficient for the jth independent variable, and ei is the additive error term. In the first stage of analysis, we estimated one such regression model for each mitochondrial signature as well as VO2 peak; i.e., each model had a single independent variable x1, representing the mitochondrial signature or VO2 peak. In the second stage of analysis, we estimated one regression model for each possible pair of mitochondrial signatures; i.e., each regression model had an independent variable x1 representing the first mitochondrial signature of the pair, and another independent variable x2 representing the second mitochondrial signature of the pair. We did this to determine which significant independent variables from the first stage of analysis were most strongly associated with τ. Finally, to understand which mitochondrial signatures were most strongly associated with τ when all are considered jointly as independent variables, we estimated a final model containing all mitochondrial signatures as joint independent predictors. In each case, we used the method of least squares to fit the model. The statistical analysis includes Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, and adjusted R2 is reported as a goodness of fit measure for each regression model.

ANCOVA analyses were conducted to investigate significant associations between the BMI or the depth of subcutaneous fat (fat layer between the 31P-surface coil and the target tissue) and the response variable (τ). Gender and age of subjects were also tested as significant confounder variables during multiple regression analysis. Details of the ANCOVA analysis can be found in supplemental information.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Variability in PCr resynthesis rate among healthy individuals

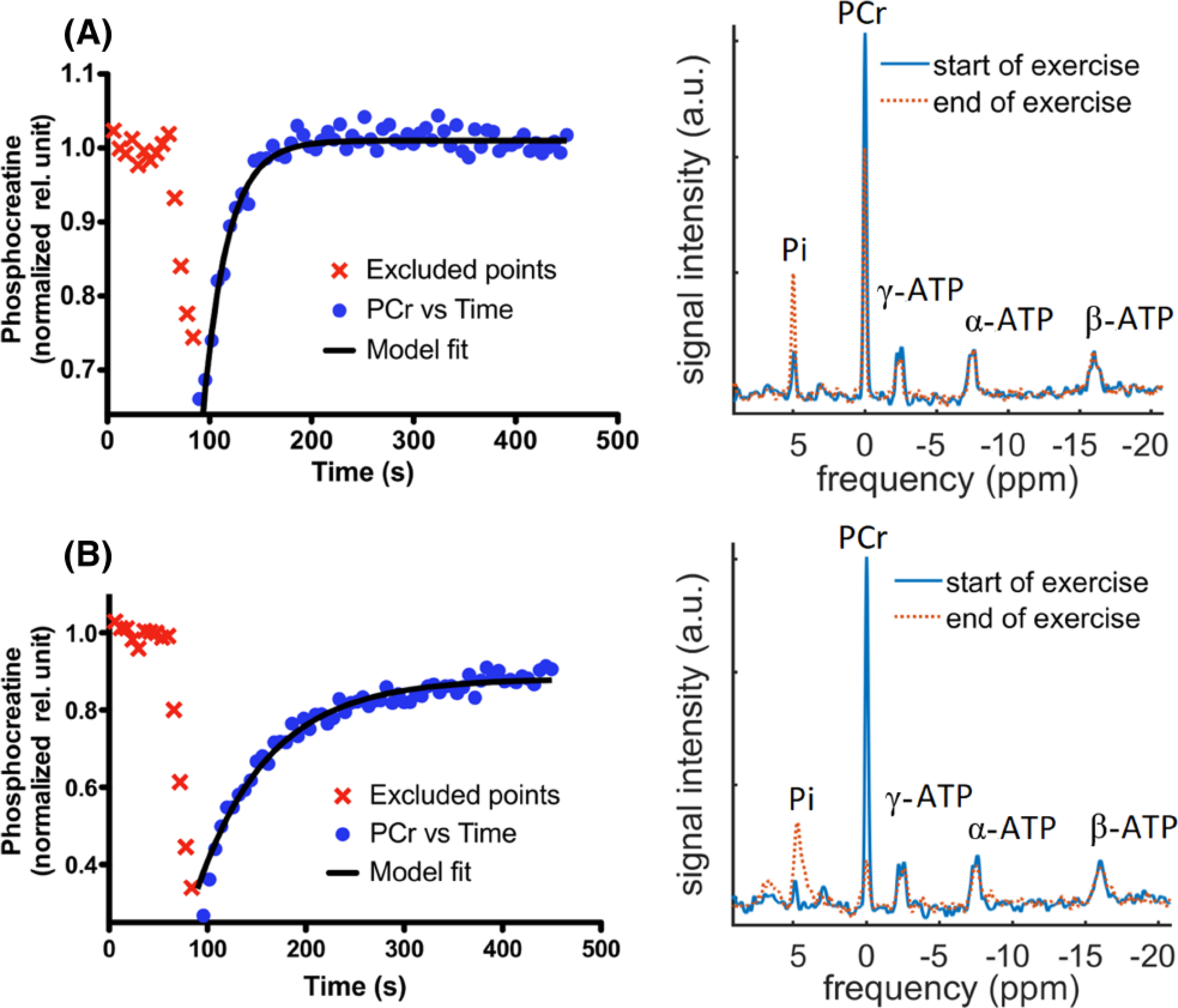

Representative time courses of submaximal exercise were analyzed for all subjects (see Table S2) and two representative curves representing individuals with fast and slow PCr resynthesis rate are illustrated in Figure 1. PCr resynthesis times calculated from mono-exponential model fits are indicated as relatively short (24.1 s) and long (73.3 s).

FIGURE 1.

Time series of PCr along with model fit of human vastus lateralis muscle (A) showing a faster PCr resynthesis rate (ie short τ = 24.12 s) and (B) showing a slower PCr resynthesis rate (ie long τ = 73.3 s) during the exercise bout. The corresponding 31P-MRS spectra are shown beside these curves

3.2 |. NAMPT is associated with variations in PCr resynthesis rates of human skeletal muscle

Parameters of linear regression were obtained in a systematic, incremental approach to regression from baseline group using “one,” “two,” or “multiple” independent variables (Tables 1 and S1). In the first stage of analysis considering only a single (“one”) independent variable, negative correlation was found between the dependent and the independent variables. NAMPT protein and mRNA levels were significantly associated with faster PCr resynthesis time at baseline (p < 0.0083) (Table 1 and Figure 2). In addition, VO2 and mRNA levels of PGC-1α, SIRT1, and NQO1 were not significantly associated with PCr resynthesis time (Table 1 and Figure 2). Subsequently, in another regression model involving the combined analysis of a pair of independent variables, NAMPT protein was found to be more strongly associated with the outcome variable than NAMPT mRNA levels (Table S1). Finally, NAMPT protein turned out to be the only significant predictor when all of the mitochondrial signatures were considered jointly in one multiple regression model. ANCOVA analyses in Table S3 suggest that BMI and the depth of subcutaneous fat in the exercised thigh were not significantly associated with the PCr recovery time constant. Moreover, neither gender nor age were significant predictors of the PCr recovery time constant. The inclusion of these variables in multiple regression models did not substantially modify any of the associations between our independent variables of primary interest and the PCr recovery time constant. The details have been discussed in the Supporting Information.

TABLE 1.

Parameters of the linear regression model (Equation 2) using data from the baseline study visit are presented for VO2 peak, NAMPT protein, and mRNA levels of NAMPT, NQO1, PGC-1α, and SIRT1. The time constant τ is the PCr recovery time estimated from 31P-MRS measurements using Equation 1. Adjusted R2 is a goodness of fit measure for the linear regression model. The linear regression outputs are the intercept alpha (α), regression coefficient beta (β), and standard error (E). The sign of β represents positive or negative correlation between the dependent and independent variables. The magnitude of coefficient β signifies the mean change in the dependent variable for a unit change in the value of the independent variable while keeping other independent variables constant. The p-value for each independent variable is the probability of the null hypothesis that the independent variable has no relationship with the dependent variable. p < 0.0083 is considered statistically significant after applying Bonferroni correction for múltiple comparisons. “No of obs.” represents how many data items were used in each regression analysis. This number is less than total number of participants in the study due to issues in collecting the measurements, such as inadequate muscle tissue available for assays.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | β | α | E | p > |t| | Adjusted R2 | No of obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ | VO2 peak | −6.47 | 58.19 | 3.13 | 0.049 | 0.1364 | 28 |

| τ | NAMPT protein | −369.88 | 54.28 | 124.77 | 0.007 | 0.253 | 23 |

| τ | NAMPT mRNA | −29.88 | 70.36 | 10.33 | 0.008 | 0.235 | 24 |

| τ | NQO1 mRNA | −82.96 | 47.68 | 132.10 | 0.536 | 0.0176 | 23 |

| τ | PGC1a mRNA | −1.70 | 59.44 | 0.94 | 0.083 | 0.0867 | 25 |

| τ | SIRT1 mRNA | −5.85 | 48.01 | 5.49 | 0.298 | 0.0056 | 24 |

Significant variables (p < 0.0083) in bold face type.

FIGURE 2.

Scatter plot of time constant, τ (s), versus VO2 peak (mL/min/kg) from participant’s fitness test at baseline (A) and versus relative NAMPT proteins (NAMPT arbitrary units/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase arbitrary units) (B), versus NAMPT mRNA (C), versus NQO1 mRNA (D), versus PGC1α mRNA (E), and versus SIRT1 mRNA (F) of participants’ muscle biopsies at baseline. A linear fit is indicated with a line including the 95% confidence interval (CI)

4 |. DISCUSSION

We identified a significant association between 31P-MRS based measurements of PCr resynthesis rate and NAMPT protein levels in the vastus lateralis. These findings advance our knowledge of physiological mechanisms related to PCr resynthesis rate measurements made in 31P-MRS studies of the skeletal muscle.

The association between NAMPT protein levels and PCr resynthesis rate is biologically relevant, given the role it plays in energy metabolism. In mammals, NAMPT is a rate-limiting enzyme that directly catalyzes the condensation of nicotinamide (NAM) with α-D-5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate to synthesize nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN).21,22 NMN is a pivotal precursor in the biosynthesis of nicotinamide dinucleotide (NAD+). However, mammals lack the capacity to directly convert NAM into NMN. Therefore, it is biologically important to salvage and recycle NAD+. Synthesized NAD+ becomes a key cofactor in oxidative phosphorylation within the inner mitochondrial membrane. Oxidative phosphorylation leads to ATP production,23 which in turn influences the coupled reactions of creatine kinase that are crucial for contraction and relaxation of the myocyte24 and therefore critically determines PCr resynthesis rate.

Two human studies have supported the importance of NAMPT as well. In a combined group of lean and obese metabolically healthy adults and individuals with Type 2 diabetes, exercise training increased NAMPT protein in the skeletal muscle in parallel with increased post-training maximum ATP synthesis and VO2max.13 In addition, a 12-week exercise-induced reduction of plasma NAMPT (possibly due to increased muscle sequestration of NAMPT) was associated with a corresponding improvement in an oral glucose tolerance test.25 We are however presenting the first confirmation that elevated NAMPT protein levels may be directly associated with faster PCr resynthesis rate in healthy adults who did not undergo exercise training.

We did not observe significant associations between PCr resynthesis rate and additional molecular markers associated with mitochondrial function, including SIRT1, PGC-1a, and NQO1 mRNA levels, which might reflect the fact that mRNA levels do not always predict the corresponding protein levels. Although NQO1 is utilized along with NAD+ in reductase reactions,26–28 and SIRT1 utilizes NAD+ as a cofactor for protein deacetylase reactions,29,30 mitochondrial NAD+ is mostly unaffected even when there is significant SIRT1 activity.31,32 This compartmentalized usage of NAD+ protects the mitochondrial NAD+ pool, which is critical to the oxidative production of ATP. Although important for skeletal muscle functioning, the specific usage of NAD+ in other compartments outside the mitochondrion by PGC-1α, SIRT1, and NQO1 may be one reason these factors have minimal association with PCr resynthesis rate.

Our study is not without limitations. Our study only included metabolically healthy, moderately fit individuals, and it is therefore not sure whether our findings extend to additional groups such as older adults, children, endurance-trained athletes, or individuals with Type 2 diabetes, some of whom may have differing levels of NAMPT protein13 as well as different PCr resynthesis rates.2 Additionally, our measurements were specific to a single skeletal muscle, the vastus lateralis. Future work should determine the generalizability of our finding to other settings.

The skeletal muscle NAMPT protein content is known to be positively correlated with mitochondrial mass and function during exercise intervention.13 In addition, the activities of skeletal muscle mitochondrial enzymes (citrate synthase, beta-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, and cytochrome C oxidase) remain unchanged in response to exercise.33 Since the muscle fiber typology substantially influences the time to recover from exercise,34 the relationships among NAMPT content and the muscle fiber typology or distribution are also important to address but are beyond the scope of the current paper.

In summary, we found that, in healthy and moderately fit adults’ human skeletal muscle, NAMPT protein is associated with PCr resynthesis rate. This finding supports the importance of mitochondrial NAD+ and helps clarify the biological correlates of the 31P-MRS based PCr resynthesis rate signal. Specifically, the relationship between NAMPT content and the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation supports the notion that NAMPT availability may be a key regulator of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity. NAMPT protein content and NADP(H) level are correlated,35 and thus measuring NAD+ concentrations should be a measurement target in future studies, using different measurement techniques than those described here.36

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support for this research provided by National Institute of Health and Pennington Biomedical Research Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. We very much appreciate the support and contribution of Lauren M. Sparks, Connie Murla, and clinical staff of the Pennington Biomedical Clinical Cores. Also, we appreciate the diligence of our research participants throughout the duration of the study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The research project described here was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AG030226 and U01 AG020478, and funded in part by P30 DK072476 and U54 GM104940. Additional support was provided by the Pennington Biomedical Research Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BMI

body mass index

- mRNA

messenger ribonucleic acid

- NAD

nicotinamide dinucleotide

- NAM

nicotinamide

- NAMPT

nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase

- NMN

nicotinamide mononucleotide

- NQO1

NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1

- PCr

phosphocreatine

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha

- SIRT1

sirtuin 1

- VO2

rate of oxygen intake (peak/maximum)

- 31P-MRS

phosphorus MRS

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have none to declare.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prompers JJ, Jeneson JA, Drost MR, Oomens CC, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K. Dynamic MRS and MRI of skeletal muscle function and biomechanics. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(7):927–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindeboom L, Nabuurs CI, Hoeks J, et al. Long-echo time MR spectroscopy for skeletal muscle acetylcarnitine detection. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(11):4915–4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conley KE, Amara CE, Bajpeyi S, et al. Higher mitochondrial respiration and uncoupling with reduced electron transport chain content in vivo in muscle of sedentary versus active subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conley KE, Amara CE, Jubrias SA, Marcinek DJ. Mitochondrial function, fibre types and ageing: new insights from human muscle in vivo. Exp Physiol. 2007;92(2):333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards LM, Kemp GJ, Dwyer RM, et al. Integrating muscle cell biochemistry and whole-body physiology in humans: 31P-MRS data from the InSight trial. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1182):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haseler LJ, Lin A, Hoff J, Richardson RS. Oxygen availability and PCr recovery rate in untrained human calf muscle: evidence of metabolic limitation in normoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293(5):R2046–R2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haseler LJ, Lin AP, Richardson RS. Skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism in sedentary humans: 31P-MRS assessment of O2 supply and demand limitations. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97(3):1077–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broskey NT, Greggio C, Boss A, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondria in the elderly: effects of physical fitness and exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1852–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Meo S, Iossa S, Venditti P. Improvement of obesity-linked skeletal muscle insulin resistance by strength and endurance training. J Endocrinol. 2017; 234(3):R159–R181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shakil-Ur-Rehman S, Karimi H, Gillani SA. Effects of supervised structured aerobic exercise training program on fasting blood glucose level, plasma insulin level, glycemic control, and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33(3):576–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan MC, Richardson RS, Haseler LJ. Human muscle performance and PCr hydrolysis with varied inspired oxygen fractions: a 31P-MRS study. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86(4):1367–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson RS, Grassi B, Gavin TP, et al. Evidence of O2 supply-dependent VO2max in the exercise-trained human quadriceps. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86 (3):1048–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costford SR, Bajpeyi S, Pasarica M, et al. Skeletal muscle NAMPT is induced by exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298(1):E117–E126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparks LM, Redman LM, Conley KE, et al. Differences in mitochondrial coupling reveal a novel signature of mitohormesis in muscle of healthy individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(12):4994–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sparks LM, Redman LM, Conley KE, et al. Effects of 12 months of caloric restriction on muscle mitochondrial function in healthy individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(1):111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordente AG, Lopez-Vinas E, Vazquez MI, et al. Redesign of carnitine acetyltransferase specificity by protein engineering. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(32):33899–33908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moon RB, Richards JH. Determination of intracellular pH by 31P magnetic resonance. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(20):7276–7278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanhamme L, van den Boogaart A, Van Huffel S. Improved method for accurate and efficient quantification of MRS data with use of prior knowledge. J Magn Reson. 1997;129(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefan D, Cesare FD, Andrasescu A, et al. Quantitation of magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals: the jMRUI software package. Meas Sci Technol. 2009;20(10):104035–104044. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergstrom J Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1975;35(7):609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgos ES, Schramm VL. Weak coupling of ATP hydrolysis to the chemical equilibrium of human nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. Biochemistry. 2008;47(42):11086–11096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Revollo JR, Grimm AA, Imai S. The NAD biosynthesis pathway mediated by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates Sir2 activity in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(49):50754–50763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Ko Y, Delannoy M, Ludtke SJ, Chiu W, Pedersen PL. Mitochondrial ATP synthasome. Three-dimensional structure by electron microscopy of the ATP synthase in complex formation with carriers for Pi and ADP/ATP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31761–31768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudsmith LE, Neubauer S. Detection of myocardial disorders by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5(Suppl 2):S49–S56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haus JM, Solomon TP, Marchetti CM, et al. Decreased visfatin after exercise training correlates with improved glucose tolerance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(6):1255–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darpolor MM, Yen YF, Chua MS, et al. In vivo MRSI of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate metabolism in rat hepatocellular carcinoma. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(5):506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CP, Simard-Duquesne N, Ernster L, Hoberman HD. Stereochemistry of hydrogen-transfer in the energy-linked pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase and related reactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;105(3):397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li R, Bianchet MA, Talalay P, Amzel LM. The three-dimensional structure of NAD(P)H:quinone reductase, a flavoprotein involved in cancer chemoprotection and chemotherapy: mechanism of the two-electron reduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(19):8846–8850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerhart-Hines Z, Rodgers JT, Bare O, et al. Metabolic control of muscle mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation through SIRT1/PGC-1alpha. EMBO J. 2007;26(7):1913–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koltai E, Szabo Z, Atalay M, et al. Exercise alters SIRT1, SIRT6, NAD and NAMPT levels in skeletal muscle of aged rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131(1):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frederick DW, Loro E, Liu L, et al. Loss of NAD homeostasis leads to progressive and reversible degeneration of skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2016;24 (2):269–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Revollo JR, Grimm AA, Imai S. The regulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis by Nampt/PBEF/visfatin in mammals. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23(2):164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, et al. Calorie restriction increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3): 0485–0494, e76. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lievens E, Klass M, Bex T, Derave W. Muscle fiber typology substantially influences time to recover from high-intensity exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2020; 128(3):648–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao Y, Kwong M, Daemen A, et al. Metabolic response to NAD depletion across cell lines is highly variable. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):1–17, e0164166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu M, Zhu XH, Chen W. In vivo31P MRS assessment of intracellular NAD metabolites and NAD+/NADH redox state in human brain at 4 T. NMR Biomed. 2016;29(7):1010–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.