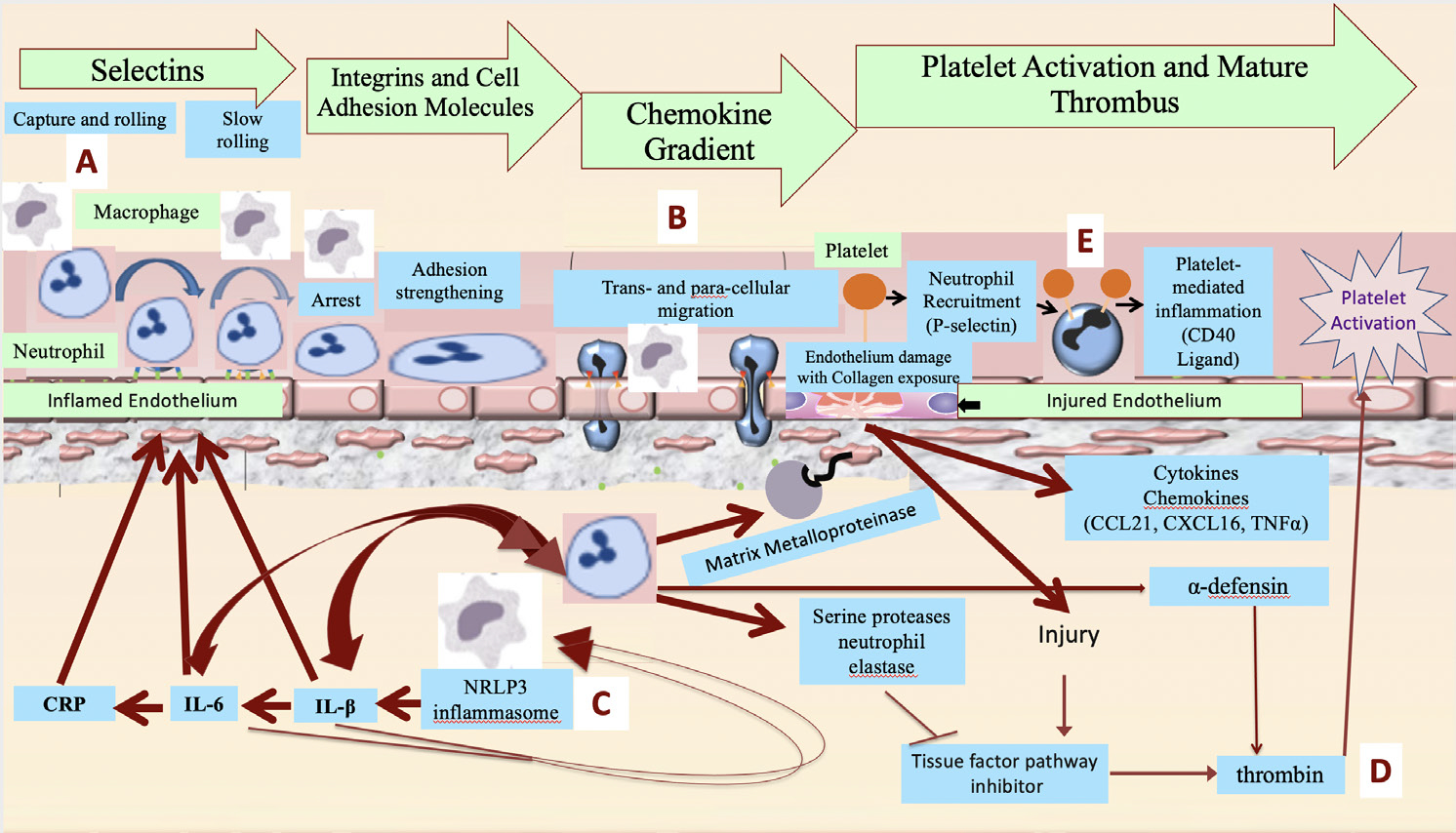

Figure 2.

Proposed pathophysiology of acute vascular inflammation in SARS-CoV-2 viral illness and potential therapeutic targets of colchicine. (A) Macrophage-driven inflammation leads to inflammasome activity, cytokine production and endothelial and neutrophil activation, with surface expression of selectins, integrins and intercellular adhesion molecules promoting neutrophil adhesion to the vasculature. Colchicine inhibits E-selectin and L-selectin expression on neutrophil and endothelial surfaces. (B) Neutrophils migrate through the endothelium following chemoattractant gradients. Colchicine impairs the rheologic properties of the neutrophil cytoskeleton, limiting theirability to transmigrate. (C) Inflammasome-generated cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6, drive additional macrophage activation and cytokine production, in an accelerating pattern known as a cytokine storm. Colchicine inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome, with the potential to prevent the development of cytokine storm. (D) Neutrophil activation releases neutrophil elastase, which inhibits tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Diminished tissue factor pathway inhibitor activity, along with endothelial injury, promote thrombin generation and platelet activation. In addition, neutrophils release α-defensin, associated with larger and more extensive thrombi. Colchicine inhibits neutrophil elastase and α-defensin release. (E) Neutrophils interact with platelets to form aggregates that are a feature of thrombosis. Colchicine decreases neutrophil-platelet aggregation. CRP, C reactive protein; IL, interleukin; NLRP3, nod-like receptor protein 3; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.