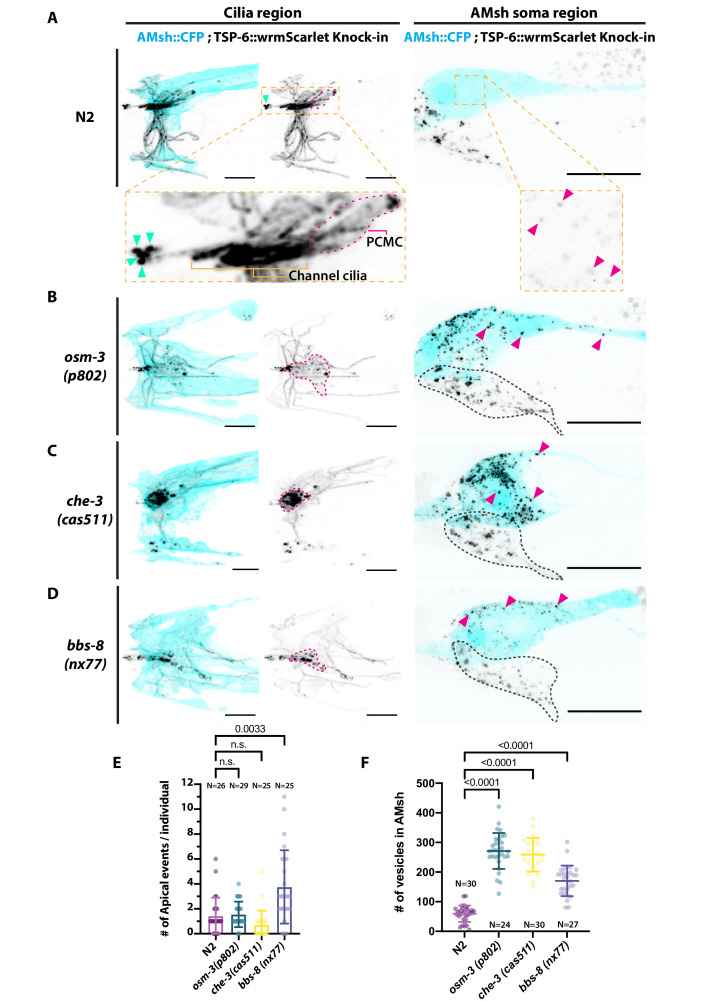

Figure 5. Ectocytosis of TSP-6-wrmScarlet to AMsh is increased in osm-3, che-3, and bbs-8 while ectocytosis of TSP-6-wrmScarlet to the amphid pore and outside is increased in bbs-8.

(A) In TSP-6-wrmScarlet knocked in strain in N2 background, TSP-6-wrmScarlet accumulated in the cilium and periciliary membrane compartment (PCMC) of the channel amphid neurons (Inset) as well as in AWC and AWA cilia. Several extracellular vesicles (EVs) were observed in amphid channel (cyan arrowheads). Left panel, scale bar: 5 μm. TSP-6-wrmScarlet was also observed in EVs located within the AMsh cytoplasm (magenta arrowheads). Right panel, scale bar: 20 μm. (B) In osm-3, TSP-6-wrmScarlet accumulated in PCMCs area (delimited by dashed magenta line). We observed more EVs in AMsh cell body (magenta arrowhead). The location of amphid neurons cell bodies is delimited by a black dashed line. (C) In che-3, TSP-6-wrmScarlet strongly accumulated in PCMCs. We observed more EVs in AMsh cell body (magenta arrowhead). (D) In bbs-8 mutants, we observed more EVs in the amphid pore (cyan arrowheads) and in the AMsh cell body (magenta arrowheads). (E) The number of apical EVs observed in each animals shows that apical release occurs in N2, osm-3, and che-3. Apical release is potentiated in bbs-8 mutants. Brown–Forsythe ANOVA, multiple comparisons corrected by Dunnett´s test. (F) The number of EVs observed in AMsh for each animals shows that TSP-6-wrmScarlet export to AMsh occurs in N2. This number of EVs observed AMsh is increased in osm-3, che-3, and bbs-8 mutants. Brown–Forsythe ANOVA, multiple comparisons corrected by Dunnett´s test.