Abstract

Cerebral white matter lesions (WML) represent a spectrum of age-related structural changes that are identified as areas of white matter high signal intensity on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Preservation of white matter requires proper functioning of both the cerebrovascular and glymphatic systems. The cerebrovascular safeguards adequate cerebral blood flow to supply oxygen, energy, and nutrients through a dynamic process of cerebral autoregulation and neurovascular coupling to keep up with global and regional demands of the brain. The glymphatic system maintains white matter integrity by preserving flow of interstitial fluid, exchanging metabolic waste and eventually its clearance into the venous circulation. Here, we argue that these two systems should not be considered separate entities but as one single physiologically integrated unit to preserve brain health. Due to the process of aging, damage to the neurovascular-glymphatic system accumulates over the life course. It is an insidious process that ultimately leads to the disruption of cerebral autoregulation, to the neurovascular uncoupling, and to the accumulation of metabolic waste products. As cerebral white matter is particularly vulnerable to hypoxic, inflammatory, and metabolic insults, WML are the first recognized pathologies of neurovascular-glymphatic dysfunction. A better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology will provide starting points for developing effective strategies to prevent a wide range of clinical disorders among which there are gait disturbances, functional dependence, cognitive impairment, and dementia.

Keywords: White matter, Neurovascular unit, Glymphatic system, Aging, Small vessel disease

Cerebral white matter lesions: normal aging or pathology?

With the widespread use of brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), more and more older adults are found to have cerebral white matter lesions (WML) [1]. WML are marked as areas of white matter high signal intensity using T2-weighted or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI which are due to an increased water content [2]. What we see on a regular MRI scan as WML are just the tip of an iceberg. More detailed brain MRI techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can demonstrate extensive microstructural alterations in these affected areas of white matter reflecting a whole spectrum of pathological changes [3, 4]. These pathologies do not represent a “new” disease as new diseases are rarely really new. Most new diseases have gone undiagnosed because they have escaped our recognition, such as WML until MRI arrived.

Prevalence of WML varies widely depending on the clinical setting and age of populations under study. WML can be found in as many as 90% of older adults with various forms of severity [5]. At the beginning, these changes in white matter were not yet recognized as signs and symptoms of disease and were thus ascribed to “normal” aging. Now we know that WML are closely related to gait disturbances, urinary incontinence, risk of cerebrovascular events, worse clinical outcomes after an acute medical condition, and cognitive impairment [6]. We and others have shown that the amount of WML builds up over time and an accelerated accumulation of WML is linked with poor prognosis [7]. WML are prototypical aging phenomena, the reflection of damage and not normal [8]. This accumulation of damage to proteins and cells leads to cerebrovascular dysfunction and culminates in brain dysfunction, disability, and an increased susceptibility to death. Therefore, the distinction between aging, pathologies, WML, and neurologic disease later in life seems in large part arbitrary [9].

The definition of a pathology is subject to current opinions and scientific understanding, and usually it is an act of intellectual creativity when the age-related changes are recognized as signs and symptoms of disease. Several studies have sought to characterize the neuropathological correlates of WML. Arteriosclerosis, morphologically dysfunctional small arteries, and stiffness of these vessels are abundantly found in the affected regions [3]. These pathologies are commonly seen in conjunction with (ischemic) degeneration of myelinated axons and neuronal damage. WML represent the process of damage accumulation of an aging brain in the absence and or failure of repair mechanisms. This accumulation of damage in white matter is an insidious process that ultimately leads to disruption of motor and sensory signal processing and, depending on individual brain vulnerability and reserve capacity, results in cognitive decline and dementia.

In this article, we discuss that an accumulated damage over the life course in two major physiologic processes in the brain, the neurovascular unit and glymphatic system, leads to the cerebrovascular dysregulations and metabolic waste products build up which directly harm the cerebral white matter. Here, we emphasize that these two systems play a complementary role in maintaining white matter homeostasis and need to be viewed as intertwined mechanisms for studying the etiologic factors underlying WML development and progression.

Neurovascular unit and brain health

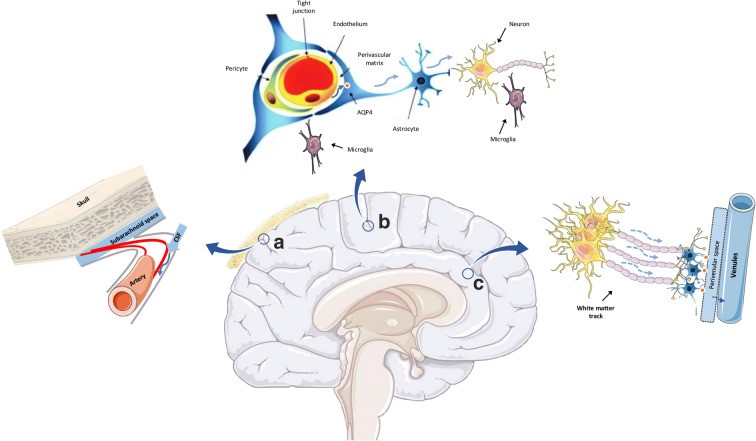

The brain is an intensely vascularized organ with an unparalleled metabolic demand. Its biological structure and functional capacity are closely tied with the integrity of its vascular bed and circulation [10]. Maintaining an adequate and efficient cerebral blood flow requires intact cardiac function, a patent vasculature over the whole heart-brain axis, and a well-regulated cerebrovascular circulation [11, 12]. Moreover, the regulation of cerebrovascular flow is dependent on the harmonized interactions between endothelium, smooth muscle cells, neurons, astrocytes, and pericytes which all together form a highly functional band named “neurovascular unit” (see Fig. 1) [15].

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the Neurovascular Unit interacting with the glymphatic system and white matter. a Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows from the subarachnoid space to the para-arterial space driven by CSF production and pulsatile arterial activity. b Movement of CSF from the perivascular space to brain parenchyma with the help of AQP-4 receptors on astrocytes. c Movement of the interstitial fluid (ISF) along the white matter tracks collecting waste products towards the perivenular and venous circulation [13, 14]

The neurovascular unit reflects the interface between the body and brain. Red blood cells carry oxygen, immune cells confer protection to pathogens, platelets provide coagulation homeostasis and a myriad of nutrients, and chemical and biochemical molecules meet and interact with the brain at this site [10, 16]. After the concept of the neurovascular unit was developed, a growing body of evidence has been produced suggesting that a proper function of this unit is closely linked with brain health [13]. The neurovascular unit is an active player in two key cerebrovascular physiologic phenomena: cerebral autoregulation and neurovascular coupling. Cerebral autoregulation ensures that the brain receives adequate and constant cerebral blood flow despite fluctuations in systemic perfusion pressure, whereas neurovascular coupling ensures that regional cerebral blood flow is adequately matched with metabolic activity [17, 18]. In brief, a flawless neurovascular unit preserves optimal flow through the macro- and micro-circulation to keep up with the necessary global and regional demands of the brain.

A well-functioning cerebrovascular system is also a prerequisite of white matter integrity. It is well-established that systemic risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking accelerate aging of the cerebrovascular system and are strongly associated with the occurrence of white matter lesions already beginning in young adulthood [19, 20]. At old age, the paucity of collateral blood vessels and insufficient blood flow reserve renders white matter extremely sensitive to hypoxic-ischemic derangements [21]. This is evident, for instance, in patients with border zone infarcts in the setting of impaired systemic perfusion pressure or upstream blood vessel stenosis/occlusion where it is mainly the subcortical white matter that is affected [22]. Oligodendrocytes are not a part of neurovascular unit; however, one of the key pathways linking the neurovascular dysfunction to WML is secondary insult to the oligodendrocytes due to ischemic, hypoxic-metabolic, and inflammatory derangements. Hypoxic-ischemic insults are particularly detrimental for oligodendrocytes, i.e., the myelin-sheath forming cells of the central nervous system (CNS) [23]. It is these oligodendrocytes that play an active role in the maintenance and repair of white matter. Damage to oligodendrocytes can incite a cascade of pathological processes that ultimately lead to neuronal apoptosis and axonal loss [24]. Of note, oligodendrocytes interact closely with various cell components in the neurovascular unit with which it constantly exchanges biological signals [25]. As an example, communications between oligodendrocytes, pericytes, and microglial cells are essential for angiogenesis, inflammatory response, repair, and remyelination of neural conduits [26].

A glymphatic system to clear the waste

The extraordinary metabolic activity of the brain requires a sophisticated system to clear metabolic waste products [27]. The lymphatic system serves as the main clearance path for most bodily organs, and as a general rule, the greater the metabolic activity, the greater is the lymphatic network in that organ [28]. For a long time, the brain seemed to lack such a clearance system as a conventional lymphatic architecture is missing. Instead, a unique structure called the “glymphatic system” has been identified and serves as the major mean to clear the brain from waste products [29]. The glymphatic system is a network of perivascular spaces in the brain that contributes to the flow of interstitial fluid exchanging waste products and ultimately the clearance of these interstitial solutes into the venous circulation (see Fig. 1). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space influxes to the brain through periarterial spaces, passes into the interstitial tissue via perivascular astrocytes, and drives the fluid and its solutes towards the perivenular space. The interstitial solutes are ultimately cleared into the sinus-associated cisternal compartments along which white matter tracks end in the deep parenchymal veins. The term glymphatic refers to the dependency of the system on the perivascular astroglial end-feet being lined up with aquaporin-4 water channels and their critical roles in response to brain tissue swelling [30].

Our understanding about the driving force behind the movement of fluids and solutes within the interstitium is evolving. Diffusion and bulk flow are likely to play major roles in movement of interstitial fluid, and it has been suggested that diffusion contributes to transport of smaller molecules over shorter distances, whereas bulk flow drives larger molecules, particularly along white matter tracks over longer distances [31]. Accumulating evidence suggests that various metabolic end-products and major pathological proteins in the brain are cleared via this pathway [14]. For instance, it has been shown that injection of fluorescently-tagged amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau are transported through the glymphatic system and drain along subcortical white matter tracts and large-caliber draining veins [32, 33]. This transport system is an active area of research, and future studies need to shed further light on the close links between (mal)function of the glymphatic system, the accumulation of pathological proteins, and brain health. Here, it should be noticed that white matter tracks are active conduits for functioning of the glymphatic system but are also maintained by the glymphatic system. This constellation implies that WML are both cause and consequence of glymphatic dysfunction. Intriguingly, WML often co-localize with another feature of cerebral small vessel disease, i.e., enlarged perivascular spaces [34]. This co-location may suggest that enlarged perivascular spaces, as WML, are not be innocent age-related bystanders but signs and symptoms of structural damage and functional impairment. Enlarged perivascular spaces are associated with abnormal collagenosis in the downstream venular system [35], and fluid stasis in the perivascular space is now interpreted as a sign of glymphatic dysfunction [36]. In addition, experimental studies have shown that dysfunction in certain components of the glymphatic system such as AQP4 water channels can have direct delirious effects on oligodendrocytes. As an example, Marigner and colleagues, using cell culture models, showed that the neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G/aquaporin-4 antibody impairs astrocytic function and secondarily leads to demyelination independent of complement activation [37]. In another experimental study, Vasas and colleagues studied the histological consequences of prolonged hydrostatic pressure injury by inducing a pathologically elevated intracranial pressure as a manifestation of glymphatic dysfunction. The intervention resulted in a prominent degree of reactive astrogliosis, a hallmark pathological feature of WML, and leads to glial scarring of perivascular, ependymal, and subependymal spaces in a neonatal feline model [38]. It has been shown that AQP4 proteins are not only involved in fluid balance regulation but also send key signals for astroglial cell migration, which occurs during glial scar formation [39].

Neurovascular-glymphatic dysfunction and white matter lesions

From the above, it becomes clear that the neurovascular unit and glymphatic system are closely related to provide the white matter with oxygen, energy, water, and nutrients; to preserve electrolyte balance; and to clean up (toxic) waste products from metabolic, maintenance, and repair activities. The cerebrovascular and glymphatic systems are complementary systems although they have distinct functional roles in nutrient supply and waste product removal. The neurovascular unit and glymphatic system closely interact at multiple levels. At a systemic level, the flow of CSF along the perivascular space is mainly driven by CSF production force and arterial pulsations [40]. Regulation of rhythmic arterial pulsation is determined by cardiac function and heart-brain axis vascular continuity. Hence, irregular cardiac function and loss of cerebrovascular vessel elasticity and compliance can both contribute to an impairment of CSF flow [41, 42]. Physiologic experiments have revealed how CSF flow along the perivascular space is synced with cardiac cycles and pulsatile wall motion of arterioles, both providing a drive force for CSF movement via the glymphatic system [43]. At the microvascular level, mediated by the structural interconnections of neurons and vessels, neural activities, regional blood flow, and clearance of metabolic byproducts are tightly matched, which again highlights the importance of proper glymphatic functioning for the neurovascular integrity and vice versa. In an experimental study, Venkat and colleagues studied white matter changes and glymphatic dysfunction in relation to multiple microinfarctions in retired breeder rats. The investigators showed that rats subjected to multiple microinfarctions developed significant degrees of white matter injuries manifested by decreased myelin thickness, oligodendrocyte progenitor cell numbers, axon density, as well as dilation of perivascular spaces and water channel dysfunction indicated by lower aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) expression around blood vessels. This study was based on an animal model of vascular dementia with no prior vascular pathologies. While the induction of vascular injury was an initiating event in this experiment, it is plausible that simultaneous dilation of the perivascular spaces and water channel dysfunction perpetuated axonal and oligodendrocyte injuries [44]. The regulation of brain homeostasis through sleep-awake cycles is a clear example how deep the structural and functional characteristics of the neurovascular unit and the glymphatic system are interwoven. The sleep-awake cycle has a major influence on the regulation of the cardiac cycle and vascular tone through activity of the autonomic nervous system [45]. Similarly, activity of the glymphatic system changes significantly during sleep-awake cycles. Experimental studies have demonstrated that the interstitial space expands considerably during sleep and this cooccurs with an increase of interstitial fluid flow and clearance of misfolded proteins [46, 47].

The neurovascular unit and glymphatic system form a structural and functional continuum for maintenance of the neuronal homeostasis, and both systems need to be taken into account to arrive at a comprehensive view on the pathophysiology of WML. Hypoperfusion at a systemic and/or local level induces oxidative stress and inflammation and is a major drive for the occurrence and progression of WML [48, 49]. Myelinated axons are particularly sensitive to ischemic and inflammatory insults as they lack a well-developed collateral vascular support system, whereas oligodendrocytes are especially vulnerable to waste metabolic product accumulation as compared to other brain cells [50, 51]. The vulnerability of white matter to those insults increases with advancing age as compensatory mechanisms progressively fail due to accumulating damage of brain structures and loss of neurovascular-glymphatic function [52, 53]. Long-lasting exposures to vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes thus accelerate brain aging and are among the most common risk factors for WML. Observations in older adults have shown that an impaired periodicity of cerebral blood flow during sleep is associated with WML [54]. Consistently, several observational studies have shown that less and lower quality of sleep is associated with both cerebrovascular dysregulation and WML [55, 56].

Implications for brain health and structural integrity

With a rapid rise in the number of old and very old individuals, the concept of healthy brain aging has received an increasing attention, and attempts have been made to determine the predictors such phenotype [57]. Age-related disorders such as dementia and stroke impose a great burden on patients, families, and healthcare systems [58]. The term “brain aging” denotes a constellation of morphological and neurophysiological alterations in the brain that ultimately leads to impairments in motor, cognitive, and social skills. Diminished neuronal activity and connectivity are among the key features in an aging brain [59]. This underscores the integral role of white matter health in maintenance of the brain function. WML are among the most common consequences of cerebral small vessel disease and are closely linked with the process of aging [60]. The occurrence of WML upon MRI examination of older adults should not be normalized in the diagnostic report as “this pattern is expected given the age of the patient.” First, it does not help when physicians convey the message that everything is “normal” when older adults themselves experience symptoms of a failing brain. The presence of WML indicates that their brain is vulnerable, identifies those at an increased risk of stroke, and is a harbinger of accelerated cognitive decline and dementia. Second, age-related presence of WML should guide scientists to unravel the complex root causes of these brain pathologies with an emphasis on the interrelation between a failure of neurovascular and glymphatic system of the brain. Third, a better understanding of this pathophysiology will provide starting points for developing effective strategies for prevention and therapy. Finally, as late-onset dementias have a long prodromal phase, there is an increasing need to define intermediate pathophysiological derangements before the brain damage becomes too extensive and irreversible. These will prove the necessary criteria when guiding preventive and therapeutic strategies to prevent cognitive disability.

In this article, we put forward a biological framework which explains how two key physiological systems act in concert to preserve the cerebral white matter integrity and dampen the adverse effects of ischemic, hypoxic, toxic, and metabolic derangements. WML are strongly related with adverse health outcomes, and understanding the pathophysiology of these pathologies is of paramount of importance for early recognition of high-risk individuals and development of preventive and therapeutic interventions. Maintenance of white matter structural and functional integrity requires a collective action of the neurovascular unit and glymphatic system in order to provide adequate energy and regulate intracellular and extracellular electrolytes and nutrient homeostasis and waste metabolic removal. This highlights the importance of developing strategies that take into account both systems as compared to the current fragmented pathophysiological models.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Behnam Sabayan declares no conflict of interest. Rudi Westendorp is supported by grants from Nordea Fonden [02–2017-1749] and Novo Nordisk Fonden Challenge Programme: Harnessing the Power of Big Data to Address the Societal Challenge of Aging [NNF17OC0027812]. These funding bodies had no influence on writing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ding T, Cohen AD, O'Connor EE, Karim HT, Crainiceanu A, Muschelli J, et al. An improved algorithm of white matter hyperintensity detection in elderly adults. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;25:102151. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merino JG. White matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging: What Is a Clinician to Do? Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:380–382. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarbu N, Shih RY, Jones RV, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Oleaga L, Smirniotopoulos JG. White matter diseases with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2016;36:1426–1447. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Groot M, Verhaaren BF, de Boer R, Klein S, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, et al. Changes in normal-appearing white matter precede development of white matter lesions. Stroke. 2013;44:1037–1042. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.680223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Achten E, Oudkerk M, Ramos LM, Heijboer R, et al. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:9–14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debette S, Schilling S, Duperron MG, Larsson SC, Markus HS. Clinical Significance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Markers of Vascular Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:81–94. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabayan B, van der Grond J, Westendorp RG, van Buchem MA, de Craen AJ. Accelerated progression of white matter hyperintensities and subsequent risk of mortality: a 12-year follow-up study. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2130–2135. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkwood TB. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell. 2005;120:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izaks GJ, Westendorp RG. Ill or just old? Towards a conceptual framework of the relation between ageing and disease. BMC Geriatr. 2003;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iadecola C. The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron. 2017;96:17–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Velpen IF, Yancy CW, Sorond FA, Sabayan B. Impaired cardiac function and cognitive brain aging. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1587–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabayan B, van Buchem MA, Sigurdsson S, Zhang Q, Meirelles O, Harris TB, Gudnason V, Arai AE, Launer LJ. Cardiac and carotid markers link with accelerated brain atrophy: the AGES-Reykjavik study (Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2246–2251. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo EH, Rosenberg GA. The neurovascular unit in health and disease: introduction. Stroke. 2009;40:S2–S3. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker EN, Bacskai BJ, Arbel-Ornath M, Aldea R, Bedussi B, Morris AW, et al. Lymphatic clearance of the brain: perivascular, paravascular and significance for neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36:181–194. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0273-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McConnell HL, Kersch CN, Woltjer RL, Neuwelt EA. The translational significance of the neurovascular unit. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:762–770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.760215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muoio V, Persson PB, Sendeski MM. The neurovascular unit - concept review. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2014;210:790–798. doi: 10.1111/apha.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Presa JL, Saravia F, Bagi Z, Filosa JA. Vasculo-neuronal coupling and neurovascular coupling at the neurovascular unit: impact of hypertension. Front Physiol. 2020;11:584135. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.584135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecrux C, Hamel E. The neurovascular unit in brain function and disease. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;203:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanimirovic DB, Friedman A. Pathophysiology of the neurovascular unit: disease cause or consequence? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1207–1221. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson W, Lewandowski AJ, Forkert ND, Griffanti L, Okell TW, Betts J, Boardman H, Siepmann T, McKean D, Huckstep O, Francis JM, Neubauer S, Phellan R, Jenkinson M, Doherty A, Dawes H, Frangou E, Malamateniou C, Foster C, Leeson P. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with MRI indices of cerebrovascular structure and function and white matter hyperintensities in young adults. JAMA. 2018;320:665–673. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernbaum M, Menon BK, Fick G, Smith EE, Goyal M, Frayne R, Coutts SB. Reduced blood flow in normal white matter predicts development of leukoaraiosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1610–1615. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momjian-Mayor I, Baron JC. The pathophysiology of watershed infarction in internal carotid artery disease: review of cerebral perfusion studies. Stroke. 2005;36:567–577. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155727.82242.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewar D, Underhill SM, Goldberg MP. Oligodendrocytes and ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:263–274. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000053472.41007.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caprariello AV, Batt CE, Zippe I, Romito-DiGiacomo RR, Karl M, Miller RH. Apoptosis of oligodendrocytes during early development delays myelination and impairs subsequent responses to demyelination. J Neurosci. 2015;35:14031–14041. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamanaka G, Ohtomo R, Takase H, Lok J, Arai K. Role of oligodendrocyte-neurovascular unit in white matter repair. Neurosci Lett. 2018;684:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamanaka G, Ohtomo R, Takase H, Lok J, Arai K. White-matter repair: Interaction between oligodendrocytes and the neurovascular unit. Brain Circ. 2018;4:118–123. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_15_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lord LD, Expert P, Huckins JF, Turkheimer FE. Cerebral energy metabolism and the brain's functional network architecture: an integrative review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1347–1354. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslin JW, Yang Y, Scallan JP, Sweat RS, Adderley SP, Murfee WL. LymphaticvVessel network structure and physiology. Compr Physiol. 2018;9:207–299. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c180015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jessen NA, Munk AS, Lundgaard I, Nedergaard M. The Glymphatic System: A Beginner's Guide. Neurochem Res. 2015;40:2583–2599. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1581-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitchen P, Salman MM, Halsey AM, Clarke-Bland C, MacDonald JA, Ishida H, et al. Targeting aquaporin-4 subcellular localization to treat central nervous system edema. Cell. 2020;181:784–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: evaluation of the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014;11:26. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg PA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ringstad G, Vatnehol SA, Eide PK. Glymphatic MRI in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain. 2017;140:2691–2705. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483–497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown WR, Moody DM, Challa VR, Thore CR, Anstrom JA. Venous collagenosis and arteriolar tortuosity in leukoaraiosis. J Neurol Sci. 2002;203-204:159–163. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(02)00283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mestre H, Kostrikov S, Mehta RI, Nedergaard M. Perivascular spaces, glymphatic dysfunction, and small vessel disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017;131:2257–2274. doi: 10.1042/CS20160381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marignier R, Nicolle A, Watrin C, Touret M, Cavagna S, Varrin-Doyer M, Cavillon G, Rogemond V, Confavreux C, Honnorat J, Giraudon P. Oligodendrocytes are damaged by neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G via astrocyte injury. Brain. 2010;133:2578–2591. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasas JT, McAllister JP, Eskandari R. Glial associated impairment of the glymphatic system in experimental neonatal hydrocephalus. Researchsquare. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-139923/v1.

- 39.Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Watanabe H, Yan D, Manley GT, Verkman AS. Involvement of aquaporin-4 in astroglial cell migration and glial scar formation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5691–5698. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kedarasetti RT, Drew PJ, Costanzo F. Arterial pulsations drive oscillatory flow of CSF but not directional pumping. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10102. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66887-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dombrowski SM, Schenk S, Leichliter A, Leibson Z, Fukamachi K, Luciano MG. Chronic hydrocephalus-induced changes in cerebral blood flow: mediation through cardiac effects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1298–1310. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mestre H, Tithof J, Du T, Song W, Peng W, Sweeney AM, et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4878. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bedussi B, Almasian M, de Vos J, VanBavel E, Bakker EN. Paravascular spaces at the brain surface: Low resistance pathways for cerebrospinal fluid flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:719–726. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17737984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkat P, Chopp M, Zacharek A, Cui C, Zhang L, Li Q, et al. Neurobiol aging. 2017;50:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgess HJ, Trinder J, Kim Y, Luke D. Sleep and circadian influences on cardiac autonomic nervous system activity. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1761–H1768. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O'Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hablitz LM, Pla V, Giannetto M, Vinitsky HS, Staeger FF, Metcalfe T, et al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4411. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18115-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernando MS, Simpson JE, Matthews F, Brayne C, Lewis CE, Barber R, Kalaria RN, Forster G, Esteves F, Wharton SB, Shaw PJ, O’Brien JT, Ince PG. White matter lesions in an unselected cohort of the elderly: molecular pathology suggests origin from chronic hypoperfusion injury. Stroke. 2006;37:1391–1398. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221308.94473.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hase Y, Horsburgh K, Ihara M, Kalaria RN. White matter degeneration in vascular and other ageing-related dementias. J Neurochem. 2018;144:617–633. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhan X, Cox C, Ander BP, Liu D, Stamova B, Jin LW, Jickling GC, Sharp FR. Inflammation combined with ischemia produces myelin injury and plaque-like aggregates of myelin, amyloid-beta and AbetaPP in adult rat brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:507–523. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosko L, Smith VN, Yamazaki R, Huang JK. Oligodendrocyte bioenergetics in health and disease. Neuroscientist. 2019;25:334–343. doi: 10.1177/1073858418793077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cox SR, Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM, Liewald DC, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Wardlaw JM, Gale CR, Bastin ME, Deary IJ. Ageing and brain white matter structure in 3,513 UK Biobank participants. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13629. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baltan S, Besancon EF, Mbow B, Ye Z, Hamner MA, Ransom BR. White matter vulnerability to ischemic injury increases with age because of enhanced excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1479–1489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5137-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee WJ, Jung KH, Park HM, Sohn CH, Lee ST, Park KI, Chu K, Jung KY, Kim M, Lee SK, Roh JK. Periodicity of cerebral flow velocity during sleep and its association with white-matter hyperintensity volume. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15510. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yaffe K, Nasrallah I, Hoang TD, Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Carnethon MR, Launer LJ, Lewis CE, Sidney S. Sleep duration and white matter quality in middle-aged adults. Sleep. 2016;39:1743–1747. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sexton CE, Zsoldos E, Filippini N, Griffanti L, Winkler A, Mahmood A, Allan CL, Topiwala A, Kyle SD, Spiegelhalder K, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, Mackay CE, Johansen-Berg H, Ebmeier KP. Associations between self-reported sleep quality and white matter in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38:5465–5473. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzales McNeal M, Zareparsi S, Camicioli R, Dame A, Howieson D, Quinn J, et al. Predictors of healthy brain aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:B294–B301. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.B294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.GBD 2017 US Neurological Disorders Collaborators. Feigin VL, Vos T, Alahdab F, Maever L, Amit A, Winfried Bärnighausen T, Beghi E, et al. Burden of neurological disorders across the US from 1990 to 2017: a global burden of disease study. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:165–176. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bishop NA, Lu T, Yankner BA. Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature. 2010;464:529–535. doi: 10.1038/nature08983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alber J, Alladi S, Bae HJ, Barton DA, Beckett LA, Bell JM, Berman SE, Biessels GJ, Black SE, Bos I, Bowman GL, Brai E, Brickman AM, Callahan BL, Corriveau RA, Fossati S, Gottesman RF, Gustafson DR, Hachinski V, Hayden KM, Helman AM, Hughes TM, Isaacs JD, Jefferson AL, Johnson SC, Kapasi A, Kern S, Kwon JC, Kukolja J, Lee A, Lockhart SN, Murray A, Osborn KE, Power MC, Price BR, Rhodius-Meester HFM, Rondeau JA, Rosen AC, Rosene DL, Schneider JA, Scholtzova H, Shaaban CE, Silva NCBS, Snyder HM, Swardfager W, Troen AM, Veluw SJ, Vemuri P, Wallin A, Wellington C, Wilcock DM, Xie SX, Hainsworth AH. White matter hyperintensities in vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID): Knowledge gaps and opportunities. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]