Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic caused high uncertainty regarding appropriate treatments and public policy reactions. This uncertainty provided a perfect breeding ground for spreading conspiratorial anti-science narratives based on disinformation. Disinformation on public health may alter the population’s hesitance to vaccinations, counted among the ten most severe threats to global public health by the United Nations. We understand conspiracy narratives as a combination of disinformation, misinformation, and rumour that are especially effective in drawing people to believe in post-factual claims and form disinformed social movements. Conspiracy narratives provide a pseudo-epistemic background for disinformed social movements that allow for self-identification and cognitive certainty in a rapidly changing information environment. This study monitors two established conspiracy narratives and their communities on Twitter, the anti-vaccination and anti-5G communities, before and during the first UK lockdown. The study finds that, despite content moderation efforts by Twitter, conspiracy groups were able to proliferate their networks and influence broader public discourses on Twitter, such as #Lockdown in the United Kingdom.

Keywords: Disinformation, Conspiracy theory, Anti-vaccination, Anti-5G, Social network analysis, COVID-19, Social movements, Twitter, Public health, Trust in government

1. Introduction

Throughout 2020 and well into 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic dominated news headlines and public conversation, resulting in a communication environment with high uncertainty. In this context, social media platforms host alternative and competing modes of online participation in civil discourse, from honest engagement in debate to disruptive or subversive communication. As governments and public health bodies battle a growing ‘infodemic’ while simultaneously dealing with the actual epidemiological emergency, conspiracy theories threaten to disrupt the effective transfer of information and erode trust in public institutions. Conspiracy narratives or theories have a long pedigree in the psychological, sociological and philosophical disciplines. Common to most interpretations is an emphasis on the pursuit, possession and denial of knowledge in the face of an epistemic adversary, usually in a position of power [1]. Combined with a perception of “nefarious intent”, the result is often an intense scepticism towards figures of authority [2]. Recent concern about conspiracy theory is pressing for two main reasons. First, it seems to be enjoying a favourable tailwind. A mainstreaming effect is edging conspiracy theories further into the public domain on the current of celebrity gossip, academic opinion and foreign state interference. Second, this phenomenon is taking place at an opportune moment. Various opinion polls indicate a general crisis of trust in governments and official institutions exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.2 3 Trust, especially in communication, has direct implications for the perceived legitimacy of institutions, which can deteriorate rapidly in times of pressure [3]. Conspiracy communities mobilising to disrupt the digital landscape may be in a position to benefit from this momentum and accelerate the effect, and therefore present a significant challenge to policymakers and communications professionals with an interest in public trust.

The purpose of this study is to explore the principles of social movement theory which is applied to conspiracy narratives. In order to do so, our research design builds on methods from social network analysis to examine the structure of relevant conspiracy communities online. Understanding the scale, density and interconnectedness of these communities will allow us to investigate our hypothesis that conspiracy groups are mobilising and increasingly interwoven during the pandemic. To facilitate that understanding and frame our analysis in a wider discussion around government intervention, we compare two time periods before and after the introduction of so-called lockdown measures in the UK on March 23, 2020. The following pages explore a conceptual framework, rooted in social movement theory, before reviewing some of the relevant empirical literature. After a description of our methodology, we present our results and discuss the findings. The evolving situation threatens to make the practice of public communication during the time of COVID-19 an altogether more complex and difficult task. With this understanding, the study concludes with a theoretical reflection of disinformed social movements and a discussion of policy implications for public institutions and governments.

2. Social movement theory & existing research

In the case of COVID-19, an existing lack of trust in governments’ and public health bodies’ handling of the pandemic appears to have become localised in the expression of specific misinformation and disinformation narratives, notably around anti-5G activism and the vaccine resistance movement. An anecdotal observation of these groups suggests a surge in activity, with existing communities being rejuvenated by increasing attention during the ‘infodemic’. In finding new avenues to express dissent, these communities are increasingly adopting a style of engagement that is characterised by militancy, which is antithetical to the norms of civil society discourse.

2.1. Theoretical framework

Given this recent mobilisation of conspiracy communities evident in their offline protest action, the comparison with more traditional social movements is becoming harder to ignore. While the theoretical concept often has positive connotations driven by a tendency to work for progressive social goals, conspiracy theory communities have been interpreted as the ’dark side of social movements’ [4], an understanding that we have found insightful in our analysis. For Touraine [5], social movements involve the combination of a principle of identity, a principle of opposition and a principle of totality — mapping these three characteristics onto the conspiracy theory literature is a useful exercise.

Community identity: In the case of conspiracy theory, community identity depends upon the pursuit, possession and denial of knowledge. Acting as membership criteria, a shared belief in specific truth claims helps to build a kind of imagined community that is united in disposition if not in history or tradition [6]. Common accusations of paranoia or delusion also help define the community, as conspiracy belief – understood as ’stigmatised knowledge’ – can lead to a minority status that consolidates a sense of belonging, even as it satisfies a narcissistic desire for uniqueness [7].

The principle of opposition: Reflecting the principle of opposition, this feeling of stigma or persecution is compounded by the perception of ’nefarious intent’ that describes the motivation for the architects of any given conspiracy [2], [5]. Trust is a fundamental component in the infrastructure of knowledge production in modern societies, which depends on things like thorough peer-review in the academic discipline, a reliable free press, and the integrity of a just government; where these institutions are perceived to have a malign agenda, trust naturally deteriorates [8], [9], [10].

The principle of totality: Well-wrought findings in empirical research show that people who follow one conspiracy theory are highly likely to believe in others and that conspiracy theorists are generally resistant to evidence that contradicts their truth claims [4], [11]. Indicating how conspiracy thinking can grow to be all-encompassing in a person’s worldview, this speaks to Touraine’s principle of totality.

While this all-encompassing effect is persuasive, we share the view that conspiracy theory belief can be accelerated in times of uncertainty when the volume and velocity of information increase significantly [12]. Our framing of conspiracy theory communities as a type of social movement resonates with recent insights from social psychology that indicate early conspiracy belief (until a certain threshold) may positively affect political engagement [13]. During the COVID-19 emergency, this clouding of the information space has been characterised as an ‘infodemic’,4 which allows misinformation and disinformation to penetrate social discourse more effectively than in ordinary circumstances. One concerning symptom of this phenomenon has been the increasing visibility of the anti-vaccination and anti-5G movements, which have generated heightened attention following their vocal participation in the global counter-lockdown movement. Since these conspiracy narratives are much talked about, but rarely explained, the following section briefly summarises their formation in recent decades.

2.2. The anti-5G and anti-vaccination movements

To give readers that are unfamiliar with the particular conspiracy theories some background we summarise the evolution of the narratives and the respective movements.

2.2.1. The anti-vaccination movement

Popular resistance to vaccination against disease has a long pedigree. Almost immediately after the introduction of vaccination acts passed in Victorian Britain, anti-vaccination leagues began to challenge the laws on legal, ethical and religious grounds [14]. These prejudices and the concomitant belief that vaccines cause more harm than good – especially in children – have persisted to the present day. The modern ‘antivax’ movement is commonly said to have been reanimated by former British physician, Andrew Wakefield, who in 1998 published an article in the medical journal The Lancet claiming to draw a connection between the Measles, Mumps & Rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism. The study – since retracted and disproved – was later declared “utterly false” by the journal editor and Wakefield was barred from practising medicine in the UK,5 but not without energising a new generation of anti-vaxxers [15].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine resistance has had a peculiar focus on Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates, whose Foundation aspires to “advance public goods for global health through technological innovation…by accelerating the development and commercialisation of novel vaccines” (among other goals).6 Seemingly provoked by Gates’ comments on the relationship between vaccinology and world population, and motivated by a surging interest in vaccines during the current epidemiological emergency, anti-vaccination activists have mobilised in protest action the world over. Significantly, the movement has developed an even more conspiratorial character, expressing a visceral reaction to the perceived financial/knowledge elite represented by Bill Gates, and “branching out into various crazy tributaries”7 including fears of embedded microchips, thought manipulation and population control.8

2.2.2. The anti-5G movement

Given its emphasis on a more modern technology, anti-5G activism has followed a much shorter timeline than that of the vaccine resistance community, although the development of these two conspiracy theories appear to follow a similar structure. While anti-vaccination sentiment resurfaces as new vaccines are made available, recurring waves of technological advances that have produced microwaves, mobile phones, WiFi, and now 5G bring new impetus to fear and scepticism for those who worry about the risks of electromagnetic radiation.9 Depending on who you ask, 5G technology is part of a plan to weaken the immune system, making people more susceptible to the virus; is an actual tool of disease transmission; or is causing direct harm through electromagnetic radiation that has required the creation of a COVID-19 hoax to cover up the real threat to human life. Claims that 5G poses a threat to human well-being have been disregarded by the World Health Organisation, and yet there continues to be serious resistance among certain communities, with anti-5G activism accelerating during the COVID-19 emergency. Arson attacks against telecoms masts and verbal and physical confrontations with telecoms engineers have been reported throughout the UK and internationally. As with vaccine resistance, anti-5G activism is extremely hostile to elites, who are often said to be pursuing a malevolent agenda that threatens the wellbeing of the general population. The assumption of “nefarious intent” in the role of various actors including the Chinese government, Chinese telecoms firm Huawei, and the World Health Organisation10 is often extreme in nature — a clear expression of the “principle of opposition” that characterises conspiracy theories and social movements more broadly.

2.3. Prior empirical research & knowledge gap

Regarding the prominence in the popular conversation, the academic literature around specific conspiracy theories is further developing in the time of COVID-19. Researchers in the field of communication studies have conducted necessary early analyses of the virality of misinformation and the associated implications for public health, while others have begun the important work of outlining the rise in xenophobic and racist attitudes apparently motivated by the origins of COVID-19 [16], [17], [18], [19]. On specific conspiracy theories, some have explored the link between the anti-5G worldview and recent violence and the apparent resilience of the anti-vaccination movement during this time of heightened attention to the necessity of vaccines [20], [21]. With the surge of conspiracy narratives and adjacent mis- and disinformation during the Coronavirus pandemic, there has been work investigating the proliferation of messages, communities and narratives on online social networks and media [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. Bruns et al. [23], for instance, focus on the proliferation of the 5G conspiracy in relation to the Coronavirus pandemic and examine Facebook data collected via Crowdtangle,11 underlining the importance of investigating the dynamics on other social platforms, such as the micro-blogging platform Twitter. Using data from Twitter, Ahmed et al. [27] analysed social networks of 5G activists, identifying the lack of a clear authority contradicting anti-5G truth claims by examining profiles using the “5GCoronavirus” keyword and #5GCoronavirus. However, limiting the analysis to only these keywords makes it difficult to draw conclusions about how conspiracy narratives and their communities might affect broader Twitter discussions such as on the so-called lockdown measures. Moreover, existing literature has not examined the intersections between different conspiracy narrative communities and the principles of social movements, which we relate to our theoretical background of conspiracy narrative communities as disinformed social movements. Given the centrality of political figures and public health bodies in active social networks contemplating COVID-19 and our chief concern with trust in public institutions, we have instead opted for wider selection criteria when building our network for analysis, including a greater variety of relevant hashtags [28]. In this way, we hope to posit a broader set of claims about the changing structure of conspiracy theories, the implications for institutions that place a high value on public trust, and the ultimate potency of conspiracy narratives and disinformation during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methodology

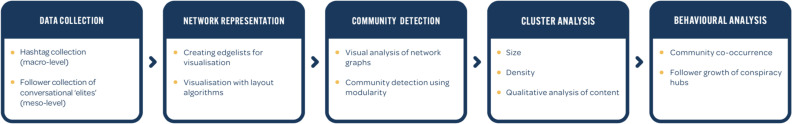

Twitter has become a crucial tool in public and political communication since it is used globally by politicians, journalists and citizens who interact in open and direct conversation; however, it is also recognised as a major forum for health misinformation with regards to conspiracy theory during COVID-19 [22], [24], [25], [26], [29], [30]. Given this two-sided characteristic and our interest in the congruence of misinformation and public health communication, our analysis will focus on Twitter as a major platform for public communication by government institutions and international organisations. Our approach combines quantitative assessments based on message frequencies and network properties with qualitative content analysis to get a qualified impression of content shared in the examined networks. We also introduce material such as screenshots of content to give the reader an impression of the characteristics of different content types and messages referring to broader conspiracy narratives. Our research benefits from prior studies that analysed the networked architecture of social platforms to determine political polarisation strategies [31] or the dynamics of conspiracy narratives and the communities that are active in spreading misinformation [22], [23], [25]. Social network analysis provides a tool kit to visualise and analyse the connections between social media users that allow to inspect to the formation of network clusters as online communities [32], [33], [34]. Working from this perspective, we explore the scale, density and interconnection between communities before (T1) and after (T2) the lockdown policy measures that were communicated by the UK government on March 23, 2020. We aim to draw conclusions about the evolution of the target conspiracy narratives on Twitter and the potential threat that these pose in the current communication environment. Our methodological approach is similar to [23] who use a mixed methods approach based on qualitative and quantitative analysis such as time series analysis, network analysis and a qualitative in-depth reading of messages and profiles to determine content differences between network clusters. While their approach examines the evolution of the 5G conspiracy only, our analysis assesses the growth of the 5G and anti-vaccination conversations in relation to COVID-19 and the relation to broader discourses on UK policy measures referred to as ‘lockdown’ (#lockdown). Fig. 1 summarises our research design, which is further elaborated in the following paragraphs.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the research design.

3.1. Data collection

In order to properly frame our research in the current health crisis and in the hope of drawing conclusions about the impact of COVID-19 on the structure of sceptic communities and conspiracy theories, we focused our analysis on a set of hashtags relevant to our research objective. Widely reproduced on Twitter, the performative function of slogans such as “5G Kills” and “Plandemic” is most notable where they circulate as hashtags, signalling identification with a particular sentiment or community. Since it takes considerably less effort to retweet a post than it does to paint a sign and attend a demonstration, these digital placards lower the barrier of participation in protest action. Table 1 gives an overview of the samples of our chosen hashtags collected during the observation period between 1st January and 10th June 2020. These seven hashtags were selected because of their varying emphases, covering the broad discourse around lockdown as a public health intervention (#Lockdown); targeted discussion topics around technologies that form a core part of notable conspiracy theories (#Vaccines and #5G); specific references to individuals and institutions that are prolific in international efforts to combat COVID-19 and consequently subject to allegations that resonate with our chosen conspiracy theories (#WHO and #BillGates); and two narrower examples with a direct connotation of conspiracy theory (#Plandemic and #DavidIcke) for comparison.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for the selected hashtag discourses.

| Datasets | Unique accounts | Total Tweets | Avg. Tweets | Avg. RTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Lockdown | 676,059 | 1,606,908 | 2.377 | 0.643 |

| #5G | 34,777 | 79,558 | 2.288 | 0.764 |

| #Vaccines | 29,354 | 50,540 | 1.554 | 0.784 |

| #WHO | 25,848 | 45,607 | 1.764 | 0.936 |

| #BillGates | 15,105 | 28,997 | 1.920 | 0.937 |

| #Plandemic | 13,001 | 18,845 | 1.450 | 0.641 |

| #DavidIcke | 4,810 | 7,137 | 1.484 | 0.811 |

For the operationalisation of the data collection we accessed Twitter’s application programming interfaces (API), mainly with the commercial media listening software Meltwater that also allows the retrospective collection of hashtag discourses. We also used rtweet12 and twitteR13 packages for the programming software/language R to collect the followers of selected accounts by accessing Twitter’s free REST API access.14

3.2. Network representation

Many processes and connections can be modelled as networks and in particular, the growth of internet-based communication technologies during the past two decades produces vast amounts of networked data. Our methodology, for instance, makes use of the fact that communication on Twitter is networked by design, since features like retweeting or mentioning or following a profile creates a link between two users. In social network analysis this link is called an edge, while the individuals are called nodes, which when aggregated enables graphical visualisation and statistical analysis of the emerging networks [33], [34].

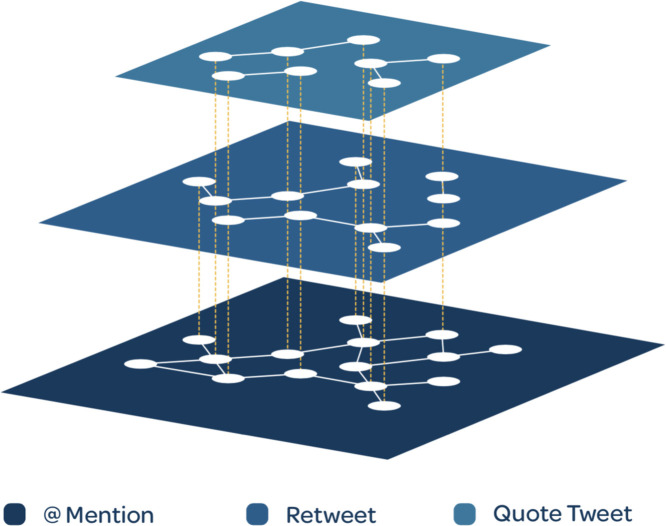

To answer our research questions the collection approach focuses on the retweet networks illustrated as the middle level in Fig. 2. Despite a trend for proclaiming “RT =/= endorsement” in Twitter bios, a RT is more likely to represent support or advocacy than an @mention or QT, both of which may express criticism, and we focus on RTs as these often indicate agreement and, thus, in aggregate illustrate a hierarchy of information diffusion and ideological support [32], [35]. Consequently, the network representation enables an analysis of discourse changes after the initiation of the lockdown measures and facilitates the automated detection of communities that will be introduced in the following section.

Fig. 2.

Conversational network types on Twitter.

3.3. Steps of analysis

3.3.1. Community detection in network graphs

In networked communication on social platforms such as Twitter, communities form due to different retweeting or mentioning behaviour of users, since not everybody retweets everybody [36]. Recent research has underlined the importance of conducting disaggregated analysis of different message types and we decide to focus on retweeting, as the most commonly used messaging type on Twitter [37]. Distinct communities in hashtag discourses – and in particular retweet networks – can represent ideological alignment or at least shared opinions on a political topic such as the so-called lockdown measures designed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 [32]. The networked structure of the data allows the interpretation and visualisation of centrality measures such as indegree and outdegree [38]. The number of times an account is retweeted is represented as incoming edges and measured by weighted indegree, whereas the opposite, outgoing edges are the number of times an account retweeted others [39]. For the visualisation we use Gephi to apply a network graph layout algorithm, ForceAtlas2, and the modularity-based Louvain algorithm for community detection, that assigns each node to a community [39], [40], [41]. We select modularity-based community detection, since the method is computationally inexpensive and integrated in Gephi [42], [43]. We also opt for a resolution of 5.0 to highlight larger communities in our network visualisation [44]. This modularity group assignment is used to colour nodes based on their community membership in the network graphs and to visualise and investigate the clustering in more detail for the next steps of analysis.

3.3.2. Qualitative content analysis of detected communities

After the automated detection of communities based on the modularity algorithm, we apply qualitative content analysis [45], [46], [47], [48]. In conversational networks from social media data, activity is often unevenly distributed, thus, we focus on the network hubs that others most often engage with to get an impression of the content and ideological alignment of different clusters. To give the reader an impression of the sort of content shared in conspiracy communities we include screenshots of messages and describe our observation of differences between communities that are visualised in the network graphs.

3.4. Co-occurrence between hashtag discourses

While some accounts might only appear in one hashtag discourse, others can appear in multiple debates and sometimes even in very similar communities, which can be an indication of strategic behaviour and a high level of ideological alignment in these groups [31], [32], [49]. This co-occurrence in retweet network clusters can happen when accounts are retweeting the same account or accounts from the same cluster. We investigate the co-following behaviour of hubs that act as conspiracy theory influencers or super-spreaders and assess whether some groups are likely to appear in multiple conspiracy communities in the selected hashtags, which would strongly indicate an involvement in supporting the propagation of these trust-undermining narratives. The evolution of this “hard core” of overlapping interests forms a central part of our hypothesis that the communications challenge posed by conspiracy theories online is increasing.

3.5. Assessing follower growth of network hubs

In order to retrospectively assess the following behaviour of accounts on Twitter we partly adapted an innovative research method that makes use of the chronological order of lists of followers and friends on Twitter [50]. Using this approach, we were able to determine the absolute and relative follower growth of the identified network hubs not just during the complete observation period, but also before and after the introduction of the UK lockdown on March 23, 2020.

4. Analysis and findings

In our literature review, we began to frame our understanding of conspiracy theory from the existing literature in a broader conversation around social movements (specifically on social networking sites) to reflect a concern about the disruptive influence of these networks in the current communication environment. This section presents the results and findings of our analysis in the context of this theoretical framework.

4.1. Exploring a spectrum

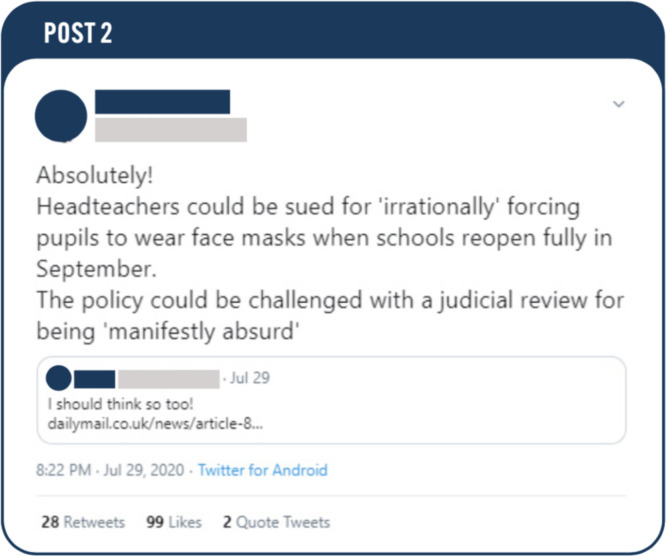

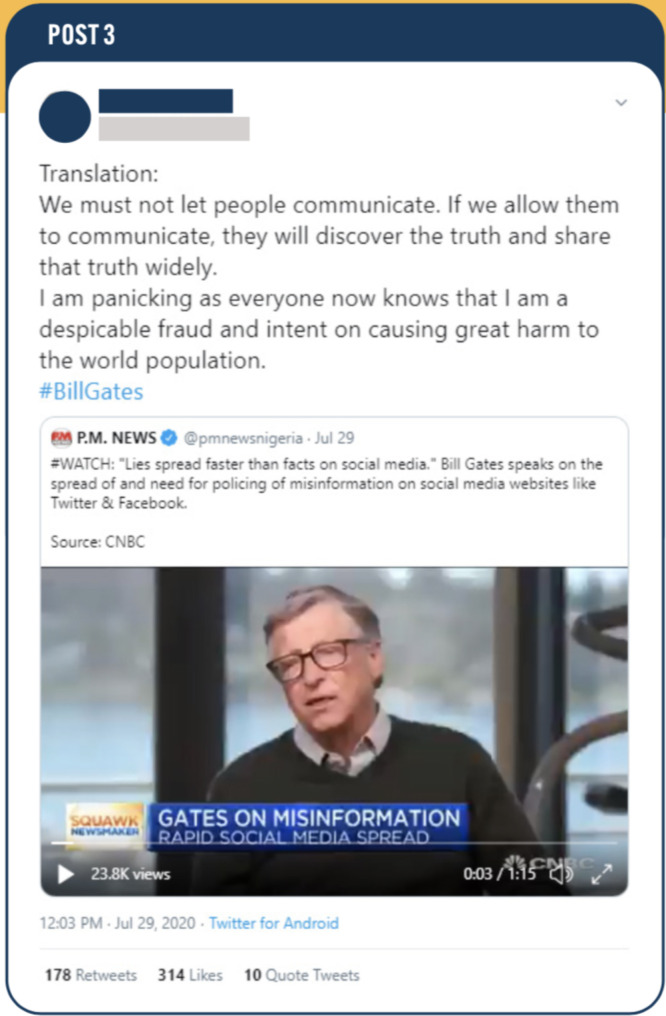

While a social movement is a neutral theoretical description, the notion is often taken to be inherently positive due to the progressive impetus that many social movements express in their efforts to change society. The line between scepticism and conspiracy thinking is admittedly unclear and accusations against elites, public health organisations and other public institutions run to varying degrees arranged on a spectrum, from contrarian opinion or dissent to more radical, and in our view more dangerous, truth claims. At one end of the spectrum, we find that many social media users endorse and promote the theory of alleged WHO complicity in a cover up of COVID-19 in the virus’ early stages, which is representative of a broad narrative circulating online Fig. A.1. Further, many of the top profiles in the various networks often publish content that contains reasonable criticism of, for example, the update to UK guidelines on mandatory face masks Fig. A.2. However, this kind of libertarian reflex is often framed alongside more outlandish claims about “nefarious intent” on the part of global financial and knowledge elites, such as Bill Gates Fig. A.3. Highlighting the principle of totality in the conspiracy theory belief system, the connections drawn between various conspiracy theories can run to an impressive degree: Fig. A.4 covers New World Order, Bill Gates, 5G, George Soros, and the Epstein scandal, all under the cover of concerns regarding chemtrails. Similarly, Fig. A.5 combines anti-5G and anti-vaccination rhetoric with an extra layer of anti-elite or “deep state” style conspiracy as expressed in mentions of WHO, Bill Gates and George Soros. We recognise this potential “dark side of social movements”, of which conspiracy theory is one example, and work from the principle that entering particular belief systems may lead to an increased intolerance towards epistemic adversaries, naturally undermining trust in the public institutions that represent the consensus view. The following section outlines an interpretation of the data, drawing on qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods to locate our findings from multiple perspectives and building to a discussion in which the implications of this research is considered in a wider context of policy and strategic communications during the time of COVID-19.

Fig. A.1.

Example Post 1.

Fig. A.2.

Example Post 2.

Fig. A.3.

Example Post 3.

Fig. A.4.

Example Post 4.

Fig. A.5.

Example Post 5.

4.2. Mapping networks before (T1) and after (T2) the introduction of the 2020 UK lockdown

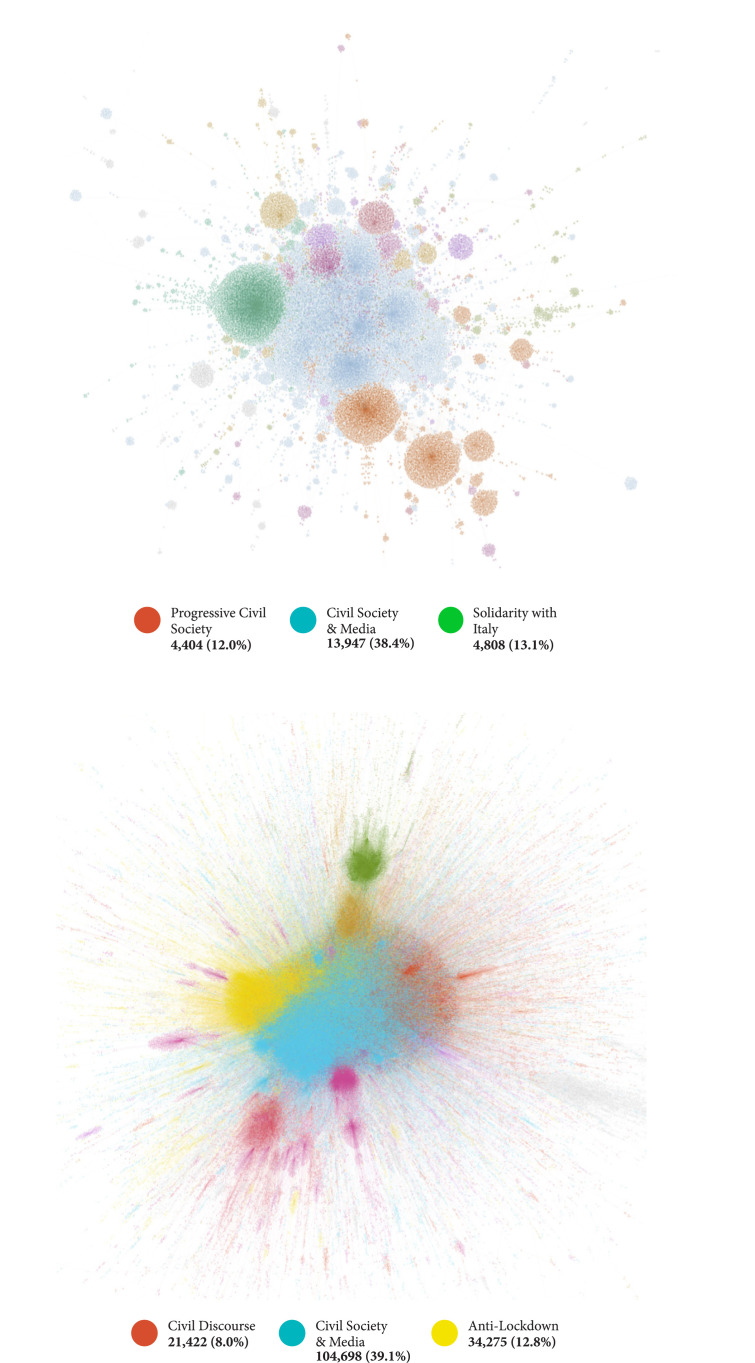

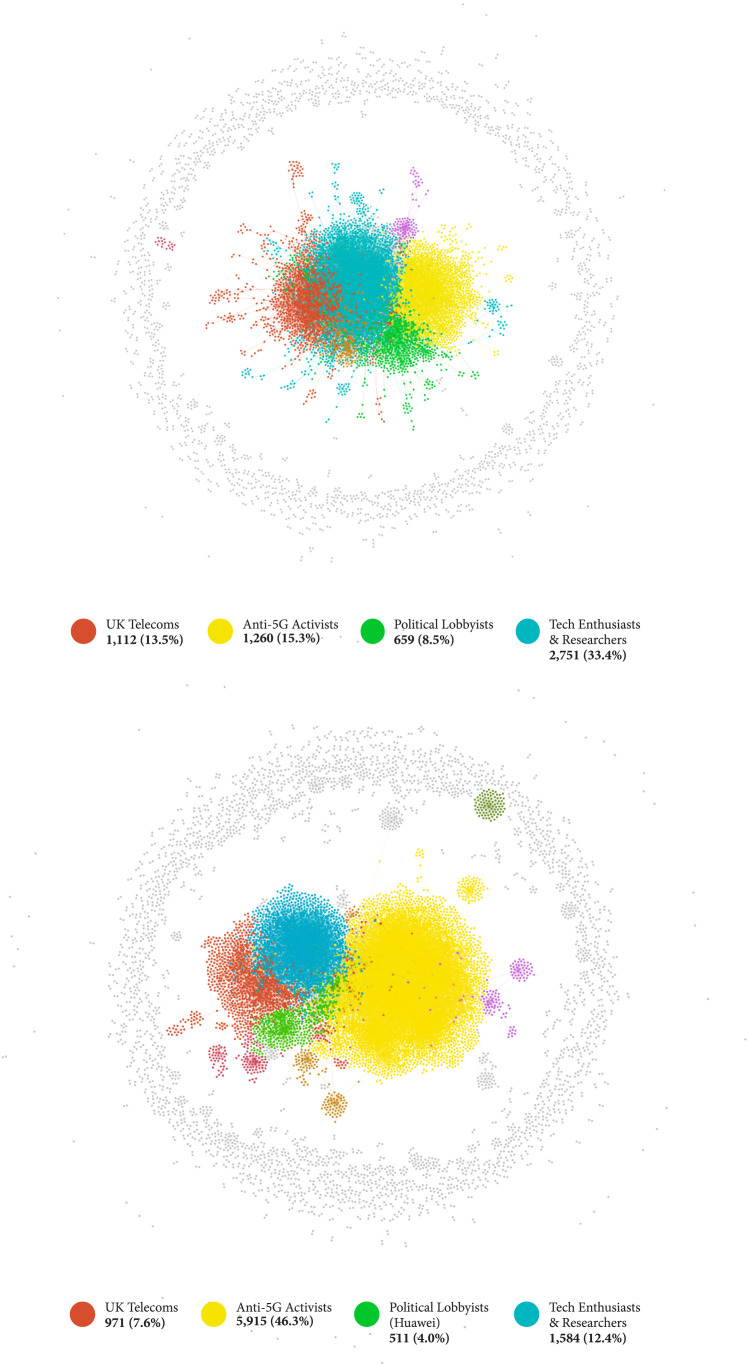

Due to the rapidly changing context following the UK government lockdown, we decided to compare data sets before and after 23rd March, giving us Time 1 (T1) of 1st January to 22nd March 2020, and Time 2 (T2) of 23rd March to 10th June 2020. We found a dramatic acceleration in the activity around our selected hashtags. Fig. A.6 illustrates the very large-scale Lockdown retweet networks that represent the conversation in T1 and T2. The RT network grew from 36,702 to 267,770 nodes representing individual accounts using the hashtag during the observation period. We also observed that the average activity of users increased, rising from 1.07 tweets per account in T1, to 2.94 tweets per account in T2. Moreover, we named the clusters based on a qualitative content assessment of most retweeted messages and accounts in each of the network clusters. Comparing the time periods before and after the UK lockdown was announced on 23rd March yields further interesting results about the changing proportion of conspiracy theory clusters relative to the wider hashtag discourse in which they sit. In T1, the #5G network displayed at the top in Fig. 3 was largely controlled by a coalition of two dominant clusters. The largest community, accounting for 33.4% of the RT network and highlighted in teal, contained mostly tech enthusiasts and researchers and showed some intermingling with a cluster (13.5% and highlighted in red) labelled UK Telecoms.

Fig. A.6.

#Lockdown RT networks with cluster names, relative proportion of the whole network and absolute number of nodes show the increase of the overall network and emergence of a large anti-lockdown community (yellow). Top: T1 (January 1, 2020 - March 22, 2020). Bottom: T2 (March 23, 2020 - June 10, 2020).

Fig. 3.

5G RT networks with cluster names, relative proportion of the whole network and absolute number of nodes show the increase of the overall network. Moreover, the disproportionate increase and isolation of the anti-5G community (yellow) is remarkable and outnumbers the rest of the network in absolute terms. Top: T1 (January 1, 2020 – March 22, 2020). Bottom: T2 (March 23, 2020 – June 10, 2020).

Together, these formed a professional community that appeared to be relatively coherent and organised in the network visualisation. These prominent civil society voices promise to be able to develop a credible response to misinformation and disinformation. The clusters characterised by a professional interest in 5G included active Twitter profiles that have been playing that role with some degree of success, acting as network hubs around which a lively community has developed.

However, while we expected to find that the absolute volume of profiles advocating conspiracy theory may have grown, it was surprising to find that conspiracy clusters also grew as a proportion of their respective networks. This suggests that representatives of the civil society discourse that opposes controversial truth claims have been less successful in articulating their position, which has resulted in both #Vaccines and #5G being further penetrated and increasingly characterised by conspiracy theory. This metric can only serve as a proxy, but the fact that conspiracy theory communities are growing at this rate suggests that widespread trust in the official narrative has been lacking, otherwise we would expect to see a similar effect within civil society clusters, such as the pro-vaccine lobby. That being said, an influx of new participants in the conversation are unlikely to have strong connections to any one group. As we show later, community cohesion within conspiracy groups tended to deteriorate later in the period, implying that while controversial truth claims may be an attractive ‘hook’ for social media users engaging in new topics, they may not be sufficient to build a lasting affiliation.

4.3. Network hubs & follower growth

We speculated that one potential reason for this growth in relative size was the significant increase in public attention to these discussion topics, but also that key network hubs in the conspiracy theory clusters have been adept in reaching new audiences. Earlier in this section we have seen that most selected debates and hashtags emerging during the pandemic increased in activity after the UK lockdown was introduced; it was also interesting to assess how many followers the identified conspiracy hubs gained during that period. When a new hashtag related to a socio-political issue emerges on Twitter, accounts of all sizes seek to capitalise on the momentum derived from increased popular attention and try to link to the discourse to get attention and increase their follower numbers.

The results of our analysis are displayed in Table 2 and underline the increased attention to these accounts, or conspiracy hubs, after the introduction of the lockdown on 23rd March. For key conspiracy theory hubs, the follower growth rate increased by 313% after the initiation of the lockdown, significantly more so than the comparable acceleration for civil society representatives. For both groups we saw quite large differences between the average and median, indicating the presence of outliers such as large news outlets; we therefore focused on accounts with fewer than 100,000 followers at the beginning of 2020. Consequently, the increased visibility of conspiracy theory and scale of the conspiracy clusters can partially be explained by a growth in supporters/followers of conspiracy content creators. These findings are in line with our expectations and contribute to the overall impression that conspiracy theories have significantly gained momentum on Twitter, and potentially other social platforms, during the Coronavirus pandemic.

Table 2.

Mean follower numbers and increase of conspiracy and civil society network hubs () with less then 100,000 followers between T1 (January 1, 2020 – March 22, 2020) and T2 (March 23, 2020 – June 10, 2020).

| Cluster | Mean in T1 (Median) | Mean in T2 (Median) | Mean increase in T2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conspiracy | 3,877 (2,034) | 12,133 (5,007) | 313% |

| Civil Society | 2,905 (1,118) | 7,214 (4,085) | 248% |

4.4. Network interaction & community building

One of our central research objectives was to assess the strength of the relationships within relevant conspiracy groups. Since community cohesion naturally amplifies content by building a pseudo-echo chamber and simultaneously increasing the opportunity for ideas to circulate, this contributes to a broader picture about the evolution and potency of target conspiracy theories online. The same holds true for the civil society response: an interactive approach to sharing and promoting content is a necessary means of constructing a community which can offer a strong foundation for coherent, impactful messaging campaigns. After running a community detection algorithm to differentiate between clusters of individual profiles in the RT network for each relevant hashtag, we used average weighted indegree to assess the density of each cluster. A higher average indegree – a proxy for density that represents rate of incoming RTs – indicates stronger or more frequent connections between individual accounts; conversely a lower average indegree points to weaker ties binding each cluster together. The results for the full reporting period are shown in Table 3. The #5G network stood out as being the only monitored hashtag discourse in which the main civil society community was more cohesive than the conspiracy cluster. As discussed above, #5G includes notable representation from professionals working in the telecoms industry and tech enthusiasts with an observable passion for new technologies, such as 5G. Crucially, these groups of accounts appear to have been successful in generating community cohesion, a likely result of the high degree of interaction that occurs between individuals with a shared interest online.

Table 3.

Average weighted indegree for main pro-conspiracy and civil society clusters in the RT networks.

| Hashtag | Conspiracy | Civil Society |

|---|---|---|

| #Lockdown | 4.8 | 3.2 |

| #5G | 2.3 | 4.2 |

| #Vaccines | 3.9 | 1.4 |

| #BillGates | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| #WHO | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| #Plandemic | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| #DavidIcke | 1.6 | 1.1 |

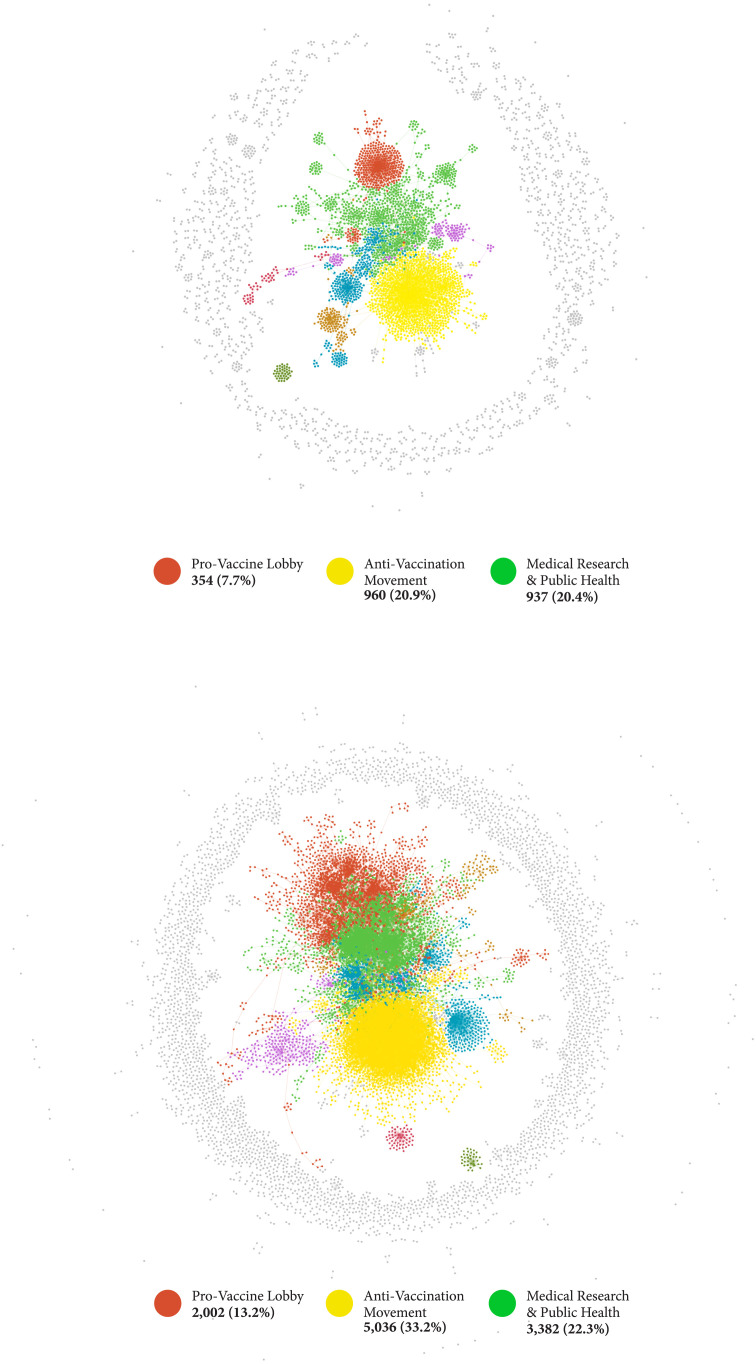

However, the standout trend shows that most of the pro-conspiracy clusters recorded a higher average indegree than their respective civil society clusters, meaning that pro-conspiracy communities tend to be more tightly linked than the communities of researchers and civil society representatives offering a viable information response. The largest anti-vaccination community in the #Vaccines discourse, for example, was just under three times more densely connected than the pro-vaccination opposition. This is further illustrated in the T1 #Vaccines RT network, shown in Fig. A.7. The largest clusters representing the anti-vaccination movement (in yellow) and the main pro-vaccine lobby (in green) are almost identical in terms of the proportion of the RT network, accounting for 20.9% and 20.4%, respectively. However, note that the anti-vaccination cluster is dense and tightly organised, whereas the main pro-vaccine group is comparatively sparse and disconnected.

Fig. A.7.

#Vaccines RT networks with cluster names, relative proportion of the whole network and absolute number of nodes show the increase of the overall network and the disproportionate increase of the anti-vaccination community (yellow). Top: T1 (January 1, 2020 - March 22, 2020). Bottom: T2 (March 23, 2020 - June 10, 2020).

Examining the change between T1 and T2, we found that density often decreased in the conspiracy communities as a large influx of new participants in the conversation resulted in a diluting effect on cohesion within clusters. This is in stark contrast to the effect on civil society clusters, most of which recorded a slight increase in density. Without a full qualitative assessment of content it is difficult to be certain about the reasons for these trends. However, an ad hoc reading of the posts in our data sets suggests that the increasing volume and proportion of the conspiracy element had something of a mobilising effect among researchers, politicians, policymakers and public health officials. It appears that these network hubs in the civil society clusters rallied to promote the scientific consensus and rebut the conspiracy theory truth claims that had begun to benefit from surging public attention.

When exploring the relevant hashtag discourses and analysing the network clusters, we had the impression of a high level of interconnectedness and interaction, especially since some key accounts were recorded among the most retweeted profiles across several networks. Consequently, we next examined the actual overlap between the networks to expose the proportion of users that co-occur in the conspiracy or civil society clusters, which would indicate a polarisation of the observed debates on the pandemic and policy measures. Key profiles across the target networks retweet and interact with one another regularly, undergirding a community of advocates across various conspiracy theories and hashtag networks. One of the main discussion topics which acts as a vector linking various discourse is Bill Gates’ work in developing vaccine technology. Bill Gates’ designation as the “voodoo doll” of conspiracy theorists during COVID-19 has been well-documented and while the proportion of the RT network using #BillGates in a conspiratorial sense is surprisingly large, this particular hashtag seems likely to attract a specific category of truth claim that features across various different discourses in a kind of cross-pollination driven by network hubs, or profiles that amplify material within the wider network. This kind of interaction and cross-pollination of ideas between different hashtag discourses represents a quantitative relationship between various communities that we explored by establishing the degree of overlap, or the proportion of accounts that feature in two or more of our target RT networks. In order to maintain focus on profiles that are proponents of conspiracy theory, we contained this portion of the analysis to RT networks on the assumption that these would be more likely to elicit support (whereas mentions and QTs allow the possibility to express criticism).

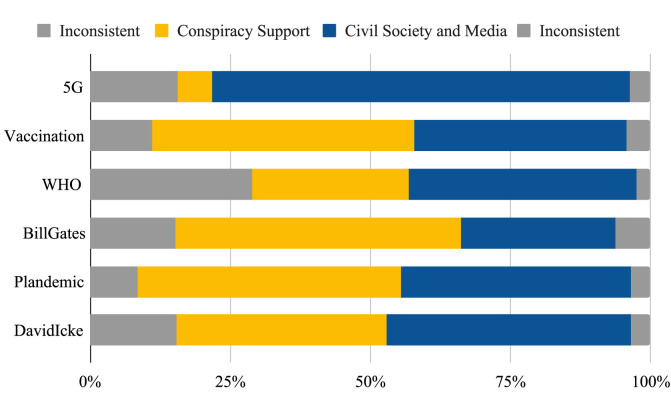

Fig. 4 shows the proportion of Twitter users in the conspiracy-adjacent cluster or the largest civil society cluster of each hashtag discourse that co-occur in the #Lockdown discourse. In other words, it represents the degree of overlap and consistency between the discussion around lockdown and the narrower conversations we tracked alongside. Since we already identified and labelled clear communities in the networks, we were able to use this information on cluster membership to determine whether an account appears consistently in the conspiracy cluster across various hashtags. We see in Fig. 4 that the consistent assignments far outweighed the inconsistent assignments, which means that the Twitter profiles captured in our data set tended to be ideologically coherent in their hashtag use. This holds true both for profiles belonging to a conspiracy theory community and to a civil society community online. We began this report with the expectation that the anti-5G and anti vaccination communities have become more connected during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has dominated public discourse in the first half of 2020. For this to be proved true, we would have to have found a higher proportion of co-occurrence between the conspiracy theory clusters the #5G and #Vaccines networks in T2.

Fig. 4.

Proportion of individual cluster nodes that co-occur in a Lockdown network cluster and the respective network cluster of another hashtag. Colours indicate the consistency of co-occurrence in a conspiracy or the largest civil society cluster of each network.

Table 4 displays that the overlapping portion between the in T2 larger conspiracy clusters in the #5G and #Vaccines networks increased by 8 percentage points. By comparison, the overlap in the civil society clusters grew by just 1pp, suggesting that new hashtag users of both hashtags in the observation period were far more likely to participate in the conversation from a conspiratorial perspective than they were to promote the scientific or civil society consensus.

Table 4.

Proportion (in %) of conspiracy and civil society cluster members that used #5G and #Vaccines between T1 (January 1, 2020 – March 22, 2020) and T2 (March 23, 2020 – June 10, 2020).

| #5G#Vaccines | T1 | T2 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conspiracy | 23.48 | 31.57 | 8.09 |

| Civil Society | 0.57 | 1.67 | 1.10 |

The data outlined above shows a notable increase in the proportion of profiles engaging in both anti-5G and anti-vaccination discussion on Twitter. The analysis also indicated that this overlap is growing at a faster rate than the comparable civil society element in these networks. Together, these findings are representative of the mobilising front of conspiracy theory belief that we recognised in anecdotal terms in our motivation to conduct this research. It is problematic to find that the natural dynamics involved here tend towards a growing and synthesising conspiracy theory community characterised by a fundamental mistrust, rather than a united civil society promoting to find a scientific consensus. In the concluding section that follows, we summarise our report, link our findings to the theoretical framework, and posit a strategy for consolidating a civil society response that may help to undermine controversial truth claims and shore up trust in public institutions as a result.

5. Discussion

This section discusses our main results, limitations and avenues for further research. We were careful in our analysis not to project too much agency onto these developments. Highlighting the evolution of various conspiracy theory communities on Twitter is not to say that recent developments have been orchestrated or that the resulting community is ideologically coherent. Rather, the changes we have described in scale, density and interconnectedness are likely to be an organic response to the uncertainty that characterises much of public discourse in relation to COVID-19. However, it is problematic to find that the natural dynamics involved here tend towards a growing and synthesising conspiracy theory community characterised by a fundamental mistrust, rather than a united civil society promoting fact-based arguments. This section discusses our main findings, limitations and avenues for further research.

5.1. Discussion of the results

One of the main research objectives guiding this study was to explore how the scale of relevant conversation has changed since the start of 2020. This covers various specific metrics, but the main takeaway suggests that the problem has indeed grown significantly, and has accelerated since the announcement of a UK lockdown on 23rd March. Part of this growth was to be expected, as for example the dramatic increase in activity around the broad hashtag discourse of #Lockdown. In some cases, the proportion of key hashtags that is controlled by communities of conspiracy theory believers was troublesome. In #BillGates, for example, the vast majority of profiles in the network belonged to a single large conspiracy theory cluster pushing material that asserted the existence of a deep state, elite agenda designed to promote vaccine technology at all costs. In terms of the evolving scale of the problem, the proportion of each network classified as conspiracy theory increased significantly after the 23rd March: the relative size of the anti-5G activist group, for example, grew to almost half of the entire #5G network. Meanwhile, the rate at which key conspiracy theory accounts accumulated new followers also increased, at an even faster rate than many of the profiles offering a response to extravagant truth claims. All of the above points to the evolution of various conspiracy communities during the time of COVID-19 and suggests a kind of organic mobilisation in response to the pandemic. On the question of density, we found that conspiracy theory communities on Twitter are likely to be far more cohesive than their respective opponent groups. A significant cluster of anti-vaccination activists, for example, was found to be 3 times more likely to engage in interactive behaviour within their cluster than the pro-vaccination lobby against which they have mobilised during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the density of the conspiracy theory clusters in both the #5G and #Vaccines networks decreased following the implementation of a UK lockdown, this is to be expected given the influx of new users engaging in these discussion topics. Reason for more concern is the apparent sparseness of groups of researchers and other representatives of civil society, which are best placed to form a united response to misinformation and disinformation on social media channels. The key learning from the professional network of 5G advocates and researchers is to build a culture of interaction and reciprocity to underline and amplify messaging that is more friendly to the pro-science, pro-evidence worldview. In our interpretation, generating a cohesive community response to questionable truth claims is an important strategy to help build trust in public health messaging online. Despite the overall disparity evident in our analysis, it has been encouraging to find that civil society communities were successful in maintaining and even increasing cohesion across the time period. An information frontier, composed of interactive relationships between a variety of actors including organisations and individual voices promoting ‘good information’, is necessary to counteract the ‘bad information’ that currently benefits from a high degree of cohesion. Lastly, we found that discourses are linked by network hubs who, on the conspiracy theory side, introduced conspiracy theory material to new audiences by transplanting hashtags into new conversations on Twitter. This tendency to penetrate new debates is representative of the potential for conspiracy clusters to polarise broader social and political discussion in charged or controversial communication environments, and is therefore an important insight and strategic consideration with regards to trust in public institutions. We also highlighted an increasing interconnectivity between the target groups of 5G and anti-vaccination activists. This development confirmed our hypothesis, which speculated the emergence or consolidation of a popular front of conspiracy theory, characterised by a fundamental mistrust in public institutions, uniting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.2. Discussion of conspiracy theories as disinformed social movements

Our conceptual framework started with the literature on social movements, working on theoretical contributions which suggest that there may be a “dark side” to some such movements. In the context of our research into digital conversations around COVID-19, we were keen to explore the different styles of online engagement that are expressed by conspiracy theory communities versus the civil society groups that contradict their truth claims. Throughout our analysis sections, we described how three key characteristics of social movements described by Touraine [5] are reflected in the behaviour of selected conspiracy theory communities:

Principle of identity: recasting this slightly as a measure of community identity, we found that 5G and anti-vaccination conspiracy groups have been adept at consolidating their ‘ingroup’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was evident as a measure of (a) scale, as conspiracy theory clusters grew over the reporting period, and (b) density, as these clusters were consistently more cohesive than their civil society counterparts, with the notable exception of an active professional network of tech enthusiasts and telecommunications industry representatives in the 5G network.

Principle of opposition: the RT networks explored in this report all contained a significant conspiracy theory element that was factually opposed to one or more civil society clusters. We interpreted this as being representative of epistemic polarisation, which in anecdotal terms was found to feed a sense among conspiracy theory elites that their truth claims were therefore validated. Where conspiracy theory elites were found to have breached community guidelines and were removed as a result, their supporters simply interpreted this as further evidence that they were ‘onto something’.

Principle of totality: this framing, or tendency to fit all new information to a very rigid worldview, shows that conspiracy theory belief can come to dominate an individual’s interpretation of the world around them. In our section on interconnectedness, we described how some profiles were highly likely to participate in multiple conspiracy theory discourses; this strength of connection between (as well as within) different conspiracy theories highlights the risk that this mode of thinking can overlap across various different discussion topics, with the potential to seed new dissent and mistrust.

Given these observations, we conclude that the conspiracy theory reaction to the COVID-19 emergency is emblematic of a broader epistemic crisis, in which normal contrarian opinion has been appropriated and accelerated by conspiracy communities. The civil society response to these developments has been inconsistent, partly because of the difficulty in coordinating such a response in an organic fashion. However, some of the key learnings from this analysis point to a central and necessary communication principle that should guide messaging strategy in relevant organisations.

5.3. Limitations and further research

Our methodological approach builds on modularity-based community detection and the qualitative assessment of the content to examine differences between the detected communities come as any method with a number of limitations. For instance, modularity values and respective cluster detection vary slightly when repeated. Due to this variation the reproducibility of the research has its limitations. However, we have publicised the edgelists of the analysed retweet networks on one of the authors’ GitHub account15 to allow for the replication of our approach and potentially a comparative analysis of the results for various community detection algorithms to test the limits of modularity maximisation for community detection [51], [52]. Regarding the qualitative assessment, the results of our interpretation could be biased by the authors’ opinions. Consequently, we integrated some content examples in the article, but due to resource restrictions and a relatively clear separation of community ideologies we refrained from having annotators double-check the community assessments. Moreover, a number of accounts and especially anti-vaccination influencers were deleted or deleted themselves during the observation period. This might be a result of Twitter’s actions against social bots and public health misinformation on their network as indicated by prior research [53], [54], [55]. The activity of social bots could be a confounder to our results or interpreting them as a representation of human behaviour. However, Twitter turned more active against inauthentic behaviour, especially with regards to health misinformation on vaccinations and the Coronavirus. While any approach comes with inherent limitations we would like to emphasise the benefit of our mixed methods approach.

More research needs to be conducted on links between large social platforms and messenger services, since after the deplatforming of influential figures their supporters have often transferred to messenger services like Telegram, Signal or Whatsapp as a reaction to the increased content moderation [56]. We hope our approach may support the identification of network hubs and conspiracy narrative communities in research and enable debunking conspiracy narratives directly and effectively in practice [57]. These direct debunking campaigns can help to foster trust into public and multilateral institutions and consequently strengthen the basis for effective public crisis communication.

5.4. Conclusions

As of end of October 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 244 million cases and upwards of 5 million fatalities worldwide.16 In these turbulent times, much emphasis has been rightly placed on the importance of clear and effective public health communication amidst surging levels of information. This article aimed to better understand one of the main factors disrupting this delicate information environment. Conspiracy theories or narratives as social movements – specifically the anti-5G and anti-vaccination movements – contradict official narratives with spurious truth claims, undermine public health messaging, and ultimately play a role in deteriorating public trust in the institutions whose role it is to safeguard citizens’ well-being and navigate our societies through the current epidemiological crisis. Anecdotally, this appeared to be driven by hostility to elites and the institutions they represent - a fundamental mistrust emerged as the key uniting factor in this particular community. Our analysis showed a notable increase in the proportion of profiles engaging in both anti-5G and anti-vaccination discussion on Twitter. The fact that this overlap is growing more than the comparable civil society element in these networks is concerning and might help to make sense of sometimes violent street protests against Coronavirus restrictions. Together, these findings illustrate the mobilising front of conspiracy theory belief that we recognised in anecdotal terms in our motivation to conduct this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Philipp Darius: Creation of the article, Conceptualisation to analysis and writing. Michael Urquhart: Creation of the article, conceptualisation to analysis and writing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

The research was funded by Media Measurement Limited. Moreover, Philipp Darius receives a Ph.D. stipend by the Hertie Foundation.

“COVID-19: government handling and confidence in health authorities”, YouGov, https://today.yougov.com/topics/international/articles-reports/2020/03/17/perception-government-handling-covid-19.

“Trust in UK government and news media COVID-19 information down, concerns over misinformation from government and politicians up”, Reuters, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/trust-uk-government-and-news-media-covid-19-information-down-concerns-over-misinformation.

1st WHO Infodemiology Conference, WHO, https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2020/06/30/default-calendar/1st-who-infodemiology-conference.

Bosely (2010), “Andrew Wakefield struck off register by General Medical Council, The Guardian.

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Strategy overview, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/what-we-do/global-health/vaccine-development-and-surveillance.

Lowe, (2020), “Vaccine Derangement”, Science Translational Medicine, https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2020/06/25/vaccine-derangement.

Evstatieva, M. (2020), “Anatomy of a COVID-19 Conspiracy Theory”, NPR, https://www.npr.org/2020/07/10/889037310/anatomy-of-a-covid-19-conspiracy-theory?t=1595434430326.

Tiffany (2020), “The Great 5G Conspiracy”, The Atlantic.

“5G mobile networks and health”, WHO, https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/radiation-5g-mobile-networks-and-health.

The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) - rtweet package, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rtweet/index.html.

The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) - twitteR package, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/twitteR/index.html.

Twitter Developer, https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api.

Johns Hopkins University, Coronavirus Resource Center, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

Appendix. Graphical appendix

See Fig. A.1, Fig. A.2, Fig. A.3, Fig. A.4, Fig. A.5, Fig. A.6, Fig. A.7.

References

- 1.Imhoff R., Lamberty P., Klein O. Using power as a negative cue: How conspiracy mentality affects epistemic trust in sources of historical knowledge. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018;44:1364–1379. doi: 10.1177/0146167218768779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewandowsky S., Cook J. 2020. The Conspiracy Theory Handbook; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidtke H. Elite legitimation and delegitimation of international organizations in the media: Patterns and explanations. Rev. Int. Organ. 2019;14:633–659. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9320-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sternisko A., Cichocka A., Van Bavel J.J. The dark side of social movements: social identity, non-conformity, and the lure of conspiracy theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020;35:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.02.007. URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352250X20300245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Touraine A. In: Social Movements: Critiques, Concepts, Case-Studies. Lyman S.M., editor. Main Trends of the Modern World; Palgrave Macmillan UK, London: 1995. Beyond social movements? pp. 371–393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson B. Verso Books; 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cichocka A., Marchlewska M., Golec de Zavala A., Olechowski M. ‘They will not control us’: Ingroup positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies. Br. J. Psychol. 2016;107:556–576. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeley B.L. Of conspiracy theories. J. Phil. 1999;96:109–126. doi: 10.2307/2564659. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2564659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aupers S. 2012. ‘Trust no one’: Modernization, paranoia and conspiracy culture - Stef Aupers, 2012. URL: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0267323111433566. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Einstein K.L., Glick D.M. Political Behavior, Vol. 37. Springer; Germany: 2015. Do I think BLS data are BS? The consequences of conspiracy theories; pp. 679–701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edy J.A., Risley-Baird E.E. Rumor communities: The social dimensions of internet political misperceptions*. Soc. Sci. Q. 2016;97:588–602. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12309. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ssqu.12309, URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ssqu.12309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchlewska M., Cichocka A., Kossowska M. Addicted to answers: Need for cognitive closure and the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs: Need for cognitive closure and conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018;48:109–117. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2308. URL: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ejsp.2308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imhoff R., Lamberty P. Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge Oxon; UK: 2020. Conspiracy theories as psycho-political reactions to perceived power; pp. 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe R.M., Sharp L.K. Anti-vaccinationists past and present. BMJ. 2002;325:430–432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7361.430. URL: https://www.bmj.com/content/325/7361/430, British Medical Journal Publishing Group, Education and debate. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussain A., Ali S., Ahmed M., Hussain S. The anti-vaccination movement: A regression in modern medicine. Cureus. 2018;10 doi: 10.7759/cureus.2919. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6122668/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budhwani H., Sun R. Creating COVID-19 stigma by referencing the novel coronavirus as the Chinese virus on Twitter: Quantitative analysis of social media data. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19301. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7205030/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kata A. A postmodern Pandora’s box: anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine. 2010;28:1709–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larson H.J. The biggest pandemic risk? Viral misinformation. Nature. 2018;562(7727):309. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07034-4. URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennycook G., McPhetres J., Zhang Y., Lu J.G., Rand D.G. 2020. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention; p. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jolley D., Paterson J.L. Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. B. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020;59:628–640. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12394. eprint: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/bjso.12394, URL: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjso.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Megget K. Even covid-19 can’t kill the anti-vaccination movement. BMJ. 2020;369:m2184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2184. URL: https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed W., Vidal-Alaball J., Downing J., López Seguí F. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of Twitter data. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruns A., Harrington S., Hurcombe E. ‘Corona? 5G? or both?’: the dynamics of COVID-19/5G conspiracy theories on Facebook. Media Inter. Aust. 2020;177:12–29. doi: 10.1177/1329878X20946113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen E., Lerman K., Ferrara E. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, Vol. 6. JMIR Publications Inc.; Toronto, Canada: 2020. Tracking social media discourse about the covid-19 pandemic: Development of a public coronavirus Twitter data set. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao A., Morstatter F., Hu M., Chen E., Burghardt K., Ferrara E., Lerman K. 2020. Political partisanship and anti-science attitudes in online discussions about covid-19. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.08498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahi G.K., Dirkson A., Majchrzak T.A. An exploratory study of COVID-19 misinformation on Twitter. Online Soc. Netw. Media. 2021;22 doi: 10.1016/j.osnem.2020.100104. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468696420300458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed W., Vidal-Alaball J., Downing J., Seguí F.L. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of Twitter data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19458. URL: https://www.jmir.org/2020/5/e19458, company: Journal of Medical Internet Research Distributor: Journal of Medical Internet Research Institution: Journal of Medical Internet Research Label: Journal of Medical Internet Research Publisher: JMIR Publications Inc. Toronto, Canada. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yum S. Social network analysis for coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 2020;101:1642–1647. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12808. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ssqu.12808, URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ssqu.12808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darius P., Stephany F. 2020. How the far-right polarises Twitter: ‘Highjacking’ hashtags in times of COVID-19. cs http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.05686. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kouzy . 2020. Cureus coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. URL: https://www.cureus.com/articles/28976-coronavirus-goes-viral-quantifying-the-covid-19-misinformation-epidemic-on-twitter. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darius P., Stephany F. 2019. Twitter “Hashjacked”: Online Polarisation Strategies of Germany’s Political Far-Right: Technical Report. SocArXiv. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/6gbc9/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conover M., Gonçalves B., Ratkiewicz J., Flammini A., Menczer F. 2011. Predicting the political alignment of Twitter users; pp. 192–199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang S., Keller F.B., Zheng L. 2016. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Examples. Google-Books-ID:2ZNlDQAAQBAJ. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott J. SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: 2017. Social Network Analysis. URL: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/social-network-analysis-4e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metaxas P. 2017. Retweets indicate agreement, endorsement, trust: A meta-analysis of published Twitter research; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.D. Boyd, S. Golder, G. Lotan, Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on twitter, in: 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2010, pp. 1–10. 10.1109/HICSS.2010.412. [DOI]

- 37.Shugars S., Gitomer A., McCabe S., Gallagher R.J., Joseph K., Grinberg N., Doroshenko L., Foucault Welles B., Lazer D. Pandemics, protests, and publics: Demographic activity and engagement on Twitter in 2020. J. Quant. Descr. Digit. Media 1. 2021 doi: 10.51685/jqd.2021.002. URL: https://journalqd.org/article/view/2570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasserman S., Faust K. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY, US: 1994. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; p. 825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.M. Bastian, S. Heymann, M. Jacomy, Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks, in: Third international AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 2009.

- 40.Blondel V.D., Guillaume J.L., Lambiotte R., Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008 doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008. arXiv:0803.0476, URL: http://arxiv.org/abs/0803.0476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacomy M., Venturini T., Heymann S., Bastian M. ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman M.E.J. Modularity and community structure in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:8577–8582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601602103. URL: https://www.pnas.org/content/103/23/8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bassett D.S., Porter M.A., Wymbs N.F., Grafton S.T., Carlson J.M., Mucha P.J. Robust detection of dynamic community structure in networks. Chaos. 2013;23 doi: 10.1063/1.4790830. URL: https://aip.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1063/1.4790830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen M., Kuzmin K., Szymanski B.K. Community detection via maximization of modularity and its variants. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2014;1:46–65. doi: 10.1109/TCSS.2014.2307458. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White M.D., Marsh E.E. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends. 2006;55:22–45. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krippendorff K. Sage Publications; 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayring P. 2014. Qualitative content analysis; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selvi A.F. The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Routledge; 2019. Qualitative content analysis; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knüpfer C., Hoffmann M., Voskresenskii V. Hijacking MeToo: transnational dynamics and networked frame contestation on the far right in the case of the ‘120 decibels’ campaign. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020:1–19. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1822904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garimella V.R.K., Weber I. 2017. A long-term analysis of polarization on Twitter; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lancichinetti A., Fortunato S. Community detection algorithms: A comparative analysis. Phys. Rev. E. 2009;80 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.056117. URL: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.80.056117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lancichinetti A., Fortunato S. Limits of modularity maximization in community detection. Phys. Rev. E. 2011;84 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.066122. URL: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.84.066122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.C.A. Davis, O. Varol, E. Ferrara, A. Flammini, F. Menczer, Botornot: A system to evaluate social bots, in: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web, 2016, pp. 273–274.

- 54.Ferrara E., Varol O., Davis C., Menczer F., Flammini A. The rise of social bots. Commun. ACM. 2016;59:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferrara E. 2020. What types of covid-19 conspiracies are populated by twitter bots? arxiv. Preprint posted April 20. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jhaver S., Boylston C., Yang D., Bruckman A. 2021. Evaluating the effectiveness of deplatforming as a moderation strategy on Twitter. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vijaykumar S., Jin Y., Rogerson D., Lu X., Sharma S., Maughan A., Fadel B., de Oliveira Costa M.S., Pagliari C., Morris D. How shades of truth and age affect responses to covid-19 (mis) information: randomized survey experiment among whatsapp users in UK and Brazil. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021;8:1–12. [Google Scholar]