Abstract

Introduction

In March 2020, South Wales experienced the most significant COVID-19 outbreak in the UK outside of London. We share our experience of the rapid redesign and subsequent change in activity in one of the busiest supra-regional burns and plastic surgery services in the UK.

Methods

A time-matched retrospective service evaluation was completed for a 7-week “COVID-19” study period and the equivalent weeks in 2018 and 2019. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate plastic surgery theatre use and the impact of service redesign. Comparison between study periods was tested for statistical significance using two-tailed t-tests.

Results

Operation numbers reduced by 64% and total operating time by 70%. General anaesthetic cases reduced from 41% to 7% (p<0.0001), and surgery was mainly carried out in ringfenced daycase theatres. Emergency surgery decreased by 84% and elective surgery by 46%. Cancer surgery as a proportion of total elective operating increased from 51% to 96% (p<0.0001). The absolute number of cancer-related surgeries undertaken was maintained despite the pandemic.

Conclusion

Rapid development of COVID-19 SOPs minimised inpatient admissions. There was a significant decrease in operating while maintaining emergency and cancer surgery. Our ringfenced local anaesthetic Plastic Surgery Treatment Centre was essential in delivering a service. COVID-19 acted as a catalyst for service innovations and the uptake of activities such as telemedicine, virtual MDTs, and online webinars. Our experiences support the need for a core burns and plastic service during a pandemic, and show that the service can be effectively redesigned at speed.

Keywords: COVID-19, Service reconfiguration, Plastic surgery, Service, Burns, Telemedicine

Introduction

The outbreak of a novel coronavirus, now termed SARS-CoV-2, was first reported in November 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Provence, China.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic in March 2020.2 Since then, COVID-19 has become the greatest current threat to global healthcare. UK hospitals have made significant changes related to workforce planning and the delivery of clinical services to prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Similarly, our service and hospital has adapted to mitigate the impact. In this manuscript, we share our experience of the rapid redesign and subsequent change in activity of our supra-regional burns and plastic surgery service, in the hope it will add to the growing body of evidence that will inform future healthcare resource planning.

Service background

The vast majority of plastic surgery operations relate to wound management and neoplasia, with a significant health economic impact.4 During 2013–2014 alone, over 1 million patients were treated in NHS England by plastic surgeons,5 and recent evidence supports an increasing workload.6 As the rate of major trauma and neoplasia continues to increase, so too does the workload for plastic surgeons. In addition, internet and media savvy patients have high expectations relating to the treatment and subsequent reconstruction.7

The Welsh Centre for Burns and Plastic Surgery has one of the busiest elective and trauma workloads in the UK, accepting referrals from thirteen hospitals covering a population of 2.3 million for plastic surgery in Central and South Wales, and 10 million for burns (the South West UK Burns Network). The workload encompasses treatment of a wide range of elective and trauma including lower limb reconstruction, upper limb reconstruction (peripheral nerve, brachial plexus and congenital hand surgery), major burns, skin cancer, head and neck, perineal and breast reconstruction, sarcoma, paediatric plastic surgery, ear reconstruction, vascular anomalies, hypospadias, laser and lymphoedema surgery. Pre-COVID-19, the unit at Morriston Hospital consisted of forty inpatient Plastic Surgery Beds, a four-bed flap monitoring unit, ten inpatient burns beds and an eight bedded burns ICU. There is additional elective operating capacity in regional hospitals within Swansea Bay University Health Board, in Neath Port Talbot Hospital and Singleton Hospital. The Clinical Service is complemented by the largest plastic surgery research group in the UK, The Reconstructive Surgery & Regenerative Medicine Research Group. The unit includes 46 clinical staff; 21 Consultants (one Professor and two Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturers), two Fellows (hand & skin cancer), 14 Registrars (five Clinical Lecturers, seven speciality Trainees and two non-training posts), seven core surgical trainees and four foundation doctors.

Response to the COVID-19 pandemic

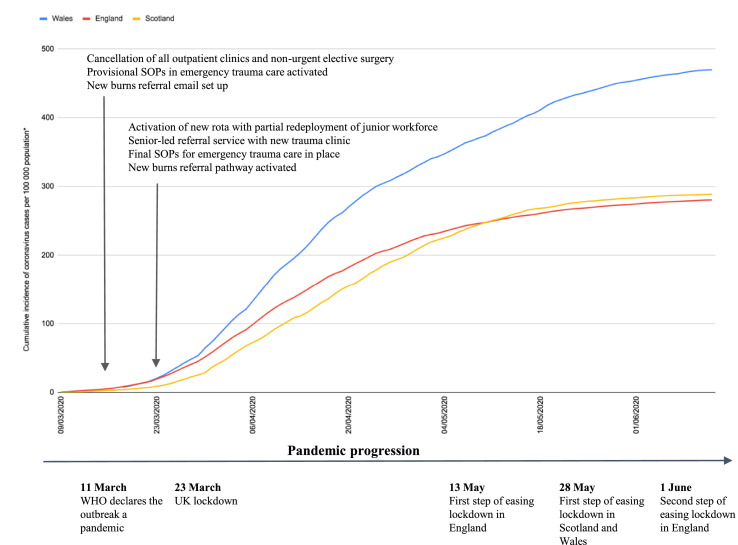

The incidence of COVID-19 in the UK began to rapidly increase in March, following trends experienced in Italy. Live government collected health data at COVID-live.co.uk showed that during March–April 2020, South Wales experienced the most significant coronavirus outbreak in the UK outside of London.8 Emergency national and local responses to the escalating threat are illustrated alongside the cumulative number of cases per 100,000 population in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of coronavirus cases per 100,000 population for England, Scotland and Wales, with a timeline of governmental and departmental pandemic measures31, 32, 33, 34

*Northern Ireland was excluded as insufficient data published on the cumulative incidence of coronavirus cases. Case rates calculated using population estimates mid-2019 sourced from the Office for National Statistics.

Service redesign was aimed at minimising transmission of COVID-19 and maximising surge capacity alongside a core service for life-saving cancer treatment, emergency burns and trauma care. Core principles were efficiency and safety while balancing the speciality-specific aerosol-generating procedural risks with the global and regional shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE).9

Trauma care

We aimed to limit the number of patient attendances and inter-hospital transfers to minimise patient-staff transmission of COVID-19. In line with speciality guidance10 , 11 and in collaboration with local stakeholders, we developed local standard operating procedures (SOPs) for common trauma presentations. SOPs were disseminated to local referring units at all levels by the clinical director, supplemented with discussions to manage trauma in-house where possible. Our tertiary service catering to facial and limb soft tissue injuries was decentralised to local orthopaedics, maxillofacial surgery and ear, nose and throat services. Senior-led triage provided specialist advice at the point of referral and expedited decision-making.

We used the transfer of clinical photographs and videos to augment patient histories and enable virtual patient management. New guidance from NHS Wales and NHSX approving the use of mobile messaging, videoconferencing and the use of clinical photographs between clinicians further augmented our emerging telemedicine service.12 , 13 A Trust email for trauma referrals and an encrypted tablet and mobile device were used for the secure transfer of confidential electronic referrals and clinical photographs. All referrals, including telephone advice to referring clinicians, and assessments were recorded in a database to ensure patient safety, safe transfer of information and long-term follow-up. All trauma referrals were discussed with the on-call consultant, and any ambiguous or complex cases were put to a collaborative consultant group forum.

A trauma clinic was introduced, with 1-h time slots, allowing staggered patient assessments and appropriate social distancing. A “see and treat” approach was adopted, with most minor operations performed under local anaesthesia in our specialised trauma clinic, the Emergency Department or minor operations suite. The creation of a “mobile procedures backpack”14 with single-use surgical instruments, local anaesthetic agents, sutures, head-torch, sterile drapes and dressings significantly expedited treatment time in less well-equipped clinical areas.

Minor procedures performed included wound debridement, nailbed repair, extensor tendon repair, digit terminalisation as well as flexor sheath washout, all of which were done under WALANT.15 More complex cases were performed in our on-site Plastic Surgery Treatment Centre (PSTC) or a peripheral day surgery unit, developed at Singleton Hospital. The latter was established as stand-alone ‘clean’ site for additional operating capacity within our regional network for the pandemic (Table 1 ). Cases requiring regional anaesthesia and consultant-led operating were booked into the peripheral hub. Patients were allocated to theatre slots at the time of referral via a virtual trauma board, reducing inefficiencies and multiple attendances. The patients were re-examined on the day of surgery to ensure the findings were consistent.

Table 1.

Service provision before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Pre-COVID-19 service provision | COVID-19 service provision |

|---|---|

| Dedicated 12-h plastic surgery trauma theatre with overnight CEPOD provision for a 24-h trauma service | Two emergency CEPOD theatres shared with other surgical specialties |

| Three dedicated plastic surgery theatres; one paediatric and two adult elective lists | One main theatre list two to three times per week for mixed case load of trauma and urgent cancer early in the pandemic |

| Two local anaesthetic day-case theatres located in a Plastic Surgery Treatment Centre (PSTC) | Continued provision of both day case lists in PSTC |

| A burns intensive care unit with two integrated burns theatres | Continued provision of burns intensive care with integrated burns theatres |

| Regional outreach clinics for burns and plastics. | All non-urgent clinics cancelled |

| Elective operating lists in regional hospitals | All elective lists in regional hospitals cancelled. Additional operating capacity in day surgery unit at Singleton Hospital established for trauma and cancer |

All referrals were screened for COVID-19 based on their early warning scores (EWS) and patient symptoms. Follow-up was minimised where possible, with those requiring it arranged locally or virtually. Hand therapy clinic was supplemented by online resources. The use of dissolvable sutures and removable splints were encouraged. Patients were trained in the self-care of wounds to reduce the burden of wound review follow-up at the hospital or general practice. Primary prevention was encouraged via public health messages using social media and reiterated through the local news. This was reinforced by national campaigns by the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) & the British Society for Surgery of the Hand (BSSH) advising the public to abstain from DIY and household renovation activities where possible.

Elective work

All non-cancer elective outpatient clinics and theatre lists were cancelled as per government guidance.3 Consultants reviewed their waiting lists and screened urgent cancers, in concordance with guidance from the NHS and speciality peer-reviewed policy recommendations.16, 17, 18, 19 Theatre capacity was reserved for life-extending or life-saving surgery. Incompletely excised or rapidly growing lesions were prioritised with risk-mitigation strategies taken, as per speciality guidance. During the initial stages of the lockdown, the existing waiting list of melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma was completely cleared in anticipation of the coming COVID-19 surge. Patients dated for SLNB and those on the SLNB waiting list at this time were all contacted by the SLNB surgeons. The BAPRAS COVID-19 guidance for melanoma was used to aid decision making; truncal melanoma patients were converted to wide local excision only and where possible this was handed back to local dermatology teams to reduce footfall through multiple hospital sites. Patients with limb melanoma, in whom it was possible to take a 1 cm margin with direct closure were listed for surgery in the Plastic Surgery Treatment Centre and listed for delayed SLNB. In those whom direct closure was not possible, wide local excision only was performed. A database for delayed SLNBs on the limbs was established to facilitate future prognostic testing for those meeting the stipulated national guidelines. When capacity in the private sector was secured, patients were listed for surgery. Initially, the lower limb delayed SLNB list was cleared with surgery taking place under spinal anaesthesia, followed by axillary SLNB under regional blocks. Patients were dated according to melanoma stage with the highest stage lesions (stage 2c/2b) listed before the stage 2a and 1b lesions.

The bulk of elective cancer operating was performed in our two dedicated local anaesthetic theatres. A skeleton crew of surgeon, scrub assistant and runner performed daily trauma and cancer lists in each theatre with staggered patient slots and temperature screening to minimise transmission risks. Full PPE was used for head and neck cases and aerosol-generating procedures such as dermatome use for split-thickness skin grafting (STSG). Where appropriate, full-thickness grafts and local flaps were chosen for reconstruction over STSG to minimise the risk of aerosols. Patients underwent pre-operative COVID-19 questionnaire assessment and a temperature test on admission.

We introduced telemedicine in the outpatient setting, using telephone consultations for new and follow-up patients. Patients were triaged remotely based on the history and clinical photographs of the lesion and booked straight onto a theatre list to minimise the number of hospital attendances. Regional lymph node status for skin cancers and sarcomas were documented on the day of surgery and any further investigations organised thereafter. Multi-disciplinary team meetings for sarcoma, head and neck cancer, and skin oncology continued via virtual teleconferencing using the Microsoft Teams platform.

Burns care

During the initial phases of the crisis, our centre was one of two in the UK alongside Chelmsford with an independent burns ITU. As such, we were not subjected to the same pressures as centres where ITUs were filled with COVID-19 patients, limiting their ability to admit ITU-level burns. The National Burns Operational Delivery Network Group published a contingency plan in which our centre was one of the ‘centres of last resort’ for referral of ITU burn patients from areas where ITUs were full. Thankfully the pandemic coincided with low numbers of burns admissions nationally, and admissions to our centre from the South West Burns Network (SWBN) have not been necessary. There was an increased focus on telemedicine. All external referrals required an email, which included clinical photographs and senior triage. Patients with small burns were discharged with patient-led wound care advice to minimise hospital attendances. Those requiring clinician-led burn follow-up were discharged to practices, district nurses, and wound management hubs. We continued to operate a virtual burns outreach service for those requiring outpatient specialist-led burn care. Intensive care burns inpatients underwent COVID-19 screening due to the anticipated need for multiple procedures and interventions, many of which are aerosol generating, i.e. bronchoalveolar lavage, intubation, tracheostomy, dermatome for STSG. Full PPE was used in theatre for staff protection given most cases necessitated the generation of aerosols.

Workforce planning

The cancellation of most elective work reduced departmental staffing needs enabling us to support surge capacity through workforce redeployment. Staff safety and well-being was designated as a priority in our reconfiguration. We ensured staff attended PPE training and upskilling, and our clinical leaders were at the forefront of lobbying for and securing high levels of PPE for all staff. Departmental teleconferences were held weekly with all doctors, senior nurses and management to provide updates, raise emerging issues and facilitate appropriate service responses. Junior doctors and the wider multidisciplinary team were included in directorate meetings to ensure their voices were heard and concerns identified.

Rota contingency planning addressed uncertainties around redeployment dates and staff COVID-19-related absence. A new rota with standby allocations at all tiers was created to ensure adequate rest and restriction of on-site attendance. Alternative rotas were planned should an entire tier be required for redeployment. This was actioned following redeployment of foundation and core trainees to the general medical COVID rota. There has been an impact on plastic surgery training nationally,20 and many of the registrars changed their research focus and increased their managerial duties to contribute support to efforts relating to the COVID pandemic.

Method of service evaluation

We performed a time-matched retrospective service evaluation for a 7-week “COVID-19″ study period, between 23 March to 10 May 2020, and the equivalent weeks in 2018 and 2019. The primary aim was to evaluate plastic surgery theatre utilisation and overall workload with secondary aims to evaluate and discuss the reasons for and implications of service redesign. All plastic surgery operations undertaken during the study periods were identified via the theatre operating management system (TOMS). Procedure, surgeon, and duration of procedure were collected. Data analysis was carried out with Microsoft Excel. Mean values were calculated for data from 2018 to 2019 and designated as “pre-COVID-19″ results. Comparison between “pre-COVID-19″ and “COVID-19″ data was tested for statistical significance using two-tailed t-tests.

Results

Operating within plastic surgery reduced by 64% overall (853.5 mean number of cases pre-COVID-19 vs. 309 cases COVID-19) (Table 2 ). Total operating time in a 7-week period reduced by 70% (1012 h mean operating hours pre-COVID-19 vs. 299 operating hours COVID-19), and the mean number of cases per day reduced from 17.4 to 6.3.

Table 2.

A comparison of theatre utilisation during pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 study periods.

| Pre-COVID-19 |

COVID-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | Mean | 2020 | |

| Operative cases | 803 | 904 | 853.5 | 309 |

| Mean cases per day | 16.4 | 18.4 | 17.4 | 6.3 |

| Total operating time (h) | 981.3 | 1043.4 | 1012.4 | 299 |

| Mean duration of operation (min) | 73.5 | 69.3 | 71.4 | 59.2 |

| Pre-COVID-19 |

COVID-19 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | Mean | Percentage of total operative cases (%) | 2020 | Percentage of total operative cases (%) | |

| Type of surgery | ||||||

| Elective surgery | 415 | 483 | 449 | 53 | 234 | 76 |

| Emergency surgery | 388 | 421 | 404.5 | 47 | 75 | 24 |

| Total cases | 803 | 904 | 853.5 | 100 | 309 | 100 |

| Elective surgery breakdown | ||||||

| Cancer-related | 208 | 254 | 231 | 51 | 225 | 96 |

| Non-cancer related | 207 | 229 | 218 | 49 | 9 | 4 |

| Total elective cases | 415 | 483 | 449 | 100 | 234 | 100 |

| Operating site | ||||||

| Main theatres (total) | 791 | 893 | 842 | 99 | 27 | 9 |

| Morriston Hospital | 734 | 773 | 27 | |||

| Neath Port Talbot Hospital | 51 | 105 | 0 | |||

| Singleton Hospital | 6 | 15 | 0 | |||

| Day case theatres (total) | 12 | 11 | 11.5 | 1 | 282 | 91 |

| Morriston Hospital Plastic Surgery Treatment Centre | 0 | 0 | 225 | |||

| Singleton Hospital | 12 | 11 | 57 | |||

| Anaesthesia | ||||||

| General anaesthesia | 347 | 346 | 346.5 | 40.6 | 23 | 7.4 |

| Local anaesthesia | 433 | 535 | 484 | 56.7 | 257 | 83.2 |

| Nerve block | 15 | 15 | 15 | 1.8 | 24 | 7.8 |

| Spinal anaesthesia | 7 | 5 | 6 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Other or not known | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Total operative cases | 803 | 904 | 853.5 | 100 | 309 | 100 |

| Primary operating surgeon | ||||||

| Consultant | 309 | 323 | 316 | 37 | 104 | 34 |

| Registrar | 455 | 533 | 494 | 58 | 134 | 43 |

| Senior house officer (core or foundation trainee) | 38 | 44 | 41 | 5 | 71 | 23 |

| Unknown | 1 | 4 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

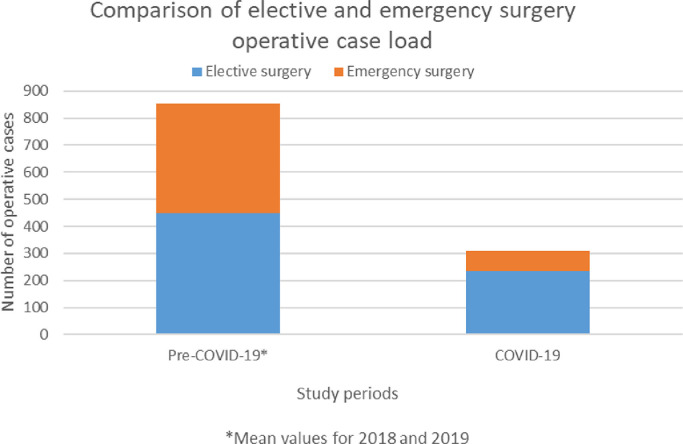

Emergency surgery decreased by 84% (404.5 mean number of cases pre-COVID-19 vs. 65 cases COVID-19), and elective surgery decreased by 46% (449 mean number of cases vs. 244 cases) (Table 2, Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

A comparison of surgical case load between the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 study periods.

Cancer-related surgery as a proportion of total elective operating significantly increased from 51% to 96% (p<0.0001). The absolute number of cancer-related surgeries undertaken was maintained despite the pandemic (231 vs. 225) (Table 3 , Figure 3 ).

Table 3.

Breakdown of operative case loads.

| Pre-COVID-19 |

COVID-19 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | Mean | Percentage of total operative cases (%) | 2020 | Percentage of total operative cases (%) | |

| Cancer surgery by sub-speciality area | ||||||

| Skin Cancer | 126 | 171 | 148.5 | 64.3 | 148 | 65.8 |

| General (Other – including diagnostic excisions) | 39 | 33 | 36 | 15.6 | 32 | 14.3 |

| Sarcoma | 10 | 13 | 11.5 | 5.0 | 14 | 6.2 |

| Head & Neck | 10 | 14 | 12 | 5.2 | 10 | 4.5 |

| Nasal Reconstruction | 6 | 14 | 10 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Occuloplastics | 8 | 5 | 6.5 | 2.8 | 14 | 6.2 |

| Breast | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Ear Reconstruction | 2 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Upper Limb | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Peripheral Nerve | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Laser | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Total cancer surgery operative cases | 208 | 254 | 231 | 100 | 225 | 100 |

Figure 3.

A comparison of elective surgery operative case load between the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 study periods.

The proportion of cases undertaken with general anaesthesia reduced from 41% to 7% (p<0.0001), local anaesthesia increased from 57% to 83% (p<0.0001) and the use of nerve blocks from 2% to 8% (p = 0.0001). Spinal anaesthesia remained the same at 1%.

Main theatre usage reduced from 99% of all operative work to 9% during COVID-19 (p<0.0001). The use of day case theatres increased from 1% to 91% (p<0.0001).

There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of operations carried out with a consultant as primary surgeon (37% vs. 34%, p = 0.252). There was an increase in senior house officer operating (5% vs. 23%, p<0.0001) and a reduction in registrar-led operating (58% vs. 43%, p<0.0001). Average duration of procedure reduced from 71.4 min to 59.2 min (p = 0.280).

Discussion

A window of opportunity, following the lessons learned in Italy and London enabled our department and hospital to evolve in order to provide the necessary surge capacity in a pandemic while maintaining a core burns and plastic surgery service. Adoption of COVID-19 SOPs minimised inpatient admissions and streamlined patient flow through our see-and-treat approach. Senior-led telemedicine enhanced the quality of our remote support to peripheral units in trauma and burn care and proved invaluable in maintaining outpatient services and MDTs during the pandemic. There was a significant reduction in operative caseload, particularly pronounced in emergency surgery (84%) (Figure 2). This was a cumulative effect of more cases being treated peripherally by local surgeons, see and treat operating by registrars in trauma clinic and the Emergency Department (not logged on TOMS) and reduced access to GA emergency theatres on the main site due to staffing and theatre redesignation as extended ITU facilities. All microsurgical equipment was available if required; however, during the study period no microsurgical cases were performed.

In line with NHS guidance emphasising the ‘equitable treatment of patients with life-threatening cancer who need access to surgical and critical care capacity, in relation to COVID-19 patients’,21 life-saving or prolonging cancer surgery as a proportion of total elective work significantly increased from 51% to 96% with the unit maintaining its absolute numbers of cancer-related surgeries (Figure 3). Unit activity was largely supported by our ringfenced local anaesthetic Plastic Surgery Treatment Centre (PTSC), a separate dedicated operating hub with two theatres, patient waiting area and recovery. We were able to maintain this hub as a “clean site” with patient screening questionnaires and observations. The drive to encourage conservative management and reduce general anaesthetic usage due to emerging evidence of high postoperative mortality rates in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection22 saw a significant reduction in GA use to 7% of all surgeries in the COVID-19 period, with enhanced uptake of local and regional block anaesthesia. The increased proportion of SHO-led operating can be explained by a shift in the complexity in the trauma. With a senior-led approach running the service & approving referrals, core surgical trainees with a plastic theme were permitted to perform routine procedures. More complex cases were performed by either a consultant or a registrar with consultant support.

The long-term impact on our patients remains a key concern. It is unknown how long this pandemic will last, and the duration of public health strategies may result in a long-lasting impact on surgical capacity. Development of ‘clean sites’ to reduce the risk of COVID-19 is likely to increase operating capacity, and guidance is evolving as research outcomes are published.23, 24, 25, 26

The reduction in outpatient clinics and elective surgeries is generating a backlog of patients.27, 28, 29 This ‘second and third wave’ of patients will have worse outcomes as a result of delay in treatment.28 , 30 Oncology patients will experience disease progression, trauma patients with delayed definitive treatment will develop more complex morbidity requiring multistage reconstruction. Collateral effects of the pandemic extend to patients who are apprehensive in seeking medical help due to the risks of contracting COVID-19 in health centres. Delayed presentations will likely lead to greater morbidity and mortality.

Conclusions

Although this represents a ‘snapshot’ of activity, our findings support the need for a core burns and plastic service during a pandemic, and show that the service can be redesigned at speed to ensure effective and safe delivery. Team spirit and compassion have been essential during the pandemic, allowing the service to adapt to changing circumstances. Junior leadership was nurtured by the service leads, with many innovations instigated by our registrar group and swiftly integrated by the consultant body. Consultants expanded remote teaching sessions for all juniors to ensure ‘standby’ periods were spent upskilling. The involvement of junior doctors in remote directorate meetings was essential in boosting morale amidst junior redeployment and staff sickness.

Although we have given patients the best possible care based on personnel & resources, we await with interest the worldwide longitudinal research studies evaluating the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient populations. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the resilience and plasticity of the department who have risen to the challenge, and the pandemic has acted as a catalyst for service innovations and activities such as telemedicine, virtual MDTs and online teaching provision. Many of these innovations have continued in practice, such as telemedicine for referrals and outpatient appointments, and ongoing use of green pathway operating sites. The primary focus is to prepare for further waves, optimise patient care in the ‘return to a new normal’, and integrate lessons learnt from shared experiences to act as a springboard for further service development.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This study did not have study sponsors.

ISW is supported by a EURAPS/AAPS Academic Scholarship. ZMJ & TD are supported by Welsh Clinical Academic Track Fellowships.

Ethics

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Writing assistance

No writing assistance was used for this study.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the BAPRAS Winter Meeting 2020.

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. Mar 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 3.Stevens S., Pritchard A. Next steps on NHS response to COVID-19. NHS Engl Lett. 2020 https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/20200317-NHS-COVID-letter-FINAL.pdf [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason L., Whitaker I., Boyce D. Dismissing the myths: an analysis of 12,483 procedures. All in a years work for a plastic surgical unit. Internet J World Health Soc Polit. 2008;6(2) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hospital Episode Statistics, Admitted Patient Care, England - 2012-13. NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity/hospital-episode-statistics-admitted-patient-care-england-2012-13 [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020 ]

- 6.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Surgical Workforce Report 2011. Available from: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/library-and-publications/non-journal-publications/rcs_workforce_report_2011.pdf [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 7.Jessop Z.M., Al-Himdani S., Clement M., Whitaker I.S. The challenge for reconstructive surgeons in the twenty-first century: manufacturing tissue-engineered solutions. Front Surg. 16 October 2015 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2015.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacMath J. COVID-19 map shows worst outbreak in mainland UK outside London is in Wales. https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/uk-news/coronavirus-map-wales-uk-COVID19-17969655 [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 9.Jessop Z.M., Dobbs T.D., Ali S.R., et al. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for surgeons during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of availability, usage, and rationing. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NHS England and NHS Improvement. Clinical guide for the management of patients requiring plastics treatment during the Coronavirus pandemic. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/specialty-guide-management-of-patients-requiring-plastics-treatment-v1.pdf [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 11.British Orthopaedic Association. Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic. Version 1 24 March 2020. https://www.boa.ac.uk/uploads/assets/ee39d8a8-9457-4533-9774e973c835246d/4e3170c2-d85f-4162-a32500f54b1e3b1f/COVID-19-BOASTs-Combined-FINAL.pdf [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 12.NHS Wales Informatics Service. COVID-19 NHS Wales Information Governance Joint Statement. https://nwis.nhs.wales/coronavirus/digital-support-updates-for-healthcare-professionals/information-governance/[Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 13.NHSX. COVID-19 Information Governance advice for staff working in health and care organisations https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/covid-19-response/data-and-information-governance/information-governance/covid-19-information-governance-advice-health-and-care-professionals/[Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 14.Ali S.R., Jovic T., Gibson J.A., Rich H., Jessop Z.M., Whitaker I.S. Evolution of plastic surgery provision due to COVID-19 – the role of the ‘pandemic pack. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lalonde D. Wide awake local anaesthesia no tourniquet technique (WALANT) BMC Proc. 2015;9(Suppl 3):A81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.NHS England and NHS Improvement. Clinical guide for the management of noncoronavirus patients requiring acute treatment: cancer. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/specialty-guide-acute-treatment-cancer-23-march-2020.pdf [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 17.British Association of Dermatologists and British Society for Dermatological Surgery. COVID-19 – Skin cancer surgery guidance Ver 1.2 30 March 2020. https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?itemtype=document&id=6670 [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 18.British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. Advice for managing BCC & SCC patients during Coronavirus pandemic. 25 March 2020. http://www.bapras.org.uk/docs/default-source/COVID-19-docs/coronavirus—skin-cancer.pdf?sfvrsn=2 [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 19.British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. Advice for managing Melanoma patients during Coronavirus pandemic. 17 March 2020. http://www.bapras.org.uk/docs/default-source/COVID-19-docs/corona-virus—melanoma—final-version-2.pdf?sfvrsn=2 [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 20.Ibrahim N., Rich H., Ali S., Whitaker I.S., Prof The effect of COVID-19 on higher plastic surgery training in the UK: a national survey of impact and damage limitation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. Jul 2021;74(7):1633–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS England and NHS Improvement. Clinical guide for the management of essential cancer surgery for adults during the coronavirus pandemic. Version 1. 7 April 2020 https://www.asgbi.org.uk/userfiles/file/covid19/c0239-specialty-guide-essential-cancer-surgery-coronavirus-v1-70420.pdf [Accessibility verified June 12, 2020]

- 22.COVIDsurg collaborative Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spinelli A., Pellino G. COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives on an unfolding crisis. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mowbray N.G., Ansell J., Horwood J., et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdelrahman T., Ansell J., Brown C., et al. Systematic review of recommended operating room practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJS Open. 2021 doi: 10.1002/bjs5.50304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdelrahman T., Beamish A.J., Brown C., et al. Surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: operating room suggestions from an international Delphi process. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nepogodiev D., Bhangu A. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Søreide K., Hallet J., Matthews J.B., Schnitzbauer A.A., et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.COVIDSurg Collaborative Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayol J., Pérez C.F. Elective surgery after the pandemic: waves beyond the horizon. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Office for National Statistics. Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, provisional: mid-2019 Statistical Bulletin. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2019 [Accessibility verified June 14, 2020]

- 32.Public Health Wales. Rapid COVID-19 surveillance confirmed case data. https://public.tableau.com/profile/public.health.wales.health.protection#!/vizhome/RapidCOVID-19virology-Public/Headlinesummary [Accessibility verified June 14, 2020]

- 33.Scottish Government. Coronavirus (COVID-19): trends in daily data. https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-trends-in-daily-data/[Accessibility verified June 14, 2020]

- 34.Public Health England. Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/[Accessibility verified June 14, 2020]