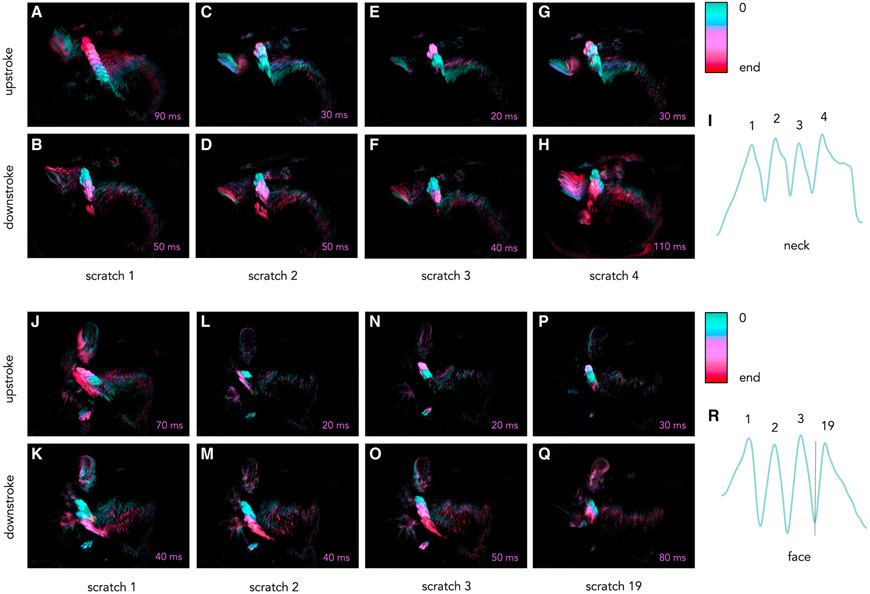

Figure 5. High-speed video allows for dissection of individual scratches within bouts of neck and face scratching.

Still frames at 10-millisecond increments were extracted from a high-speed video, and consecutive images were subtracted in ImageJ. The resulting subtracted images were overlayed, and a color scale was applied to represent time (first frame in green, middle frames in purple, and last in red; see color bar). Each image segment represents 10 milliseconds, and the total time represented in each image is shown in the bottom right corner of each image.

(A–H) A single bout of neck scratching. Shown are the upstroke (top row) and downstroke (bottom row) of all (four) individual neck scratches within a single bout.

(J–Q) A single bout of face scratching. Shown are the upstroke (top row) and downstroke (bottom row) of four individual face scratches within a single bout. Images show the first three and last (19th) scratches of the bout. A trace of the y position of the paw over time extracted from neck (I) and face (R) scratching bouts is shown on the right, with each labeled peak corresponding to the images of the same scratch.

(A and J) First scratches of a given bout have unique trajectories. In neck and face scratching, the upstroke of the first scratch is larger and more prolonged than subsequent upstrokes.

(H and Q) The downstroke of the final scratch is longer in duration in neck and face scratching, as the animal adjusts its posture to bring the paw to the mouth to lick.

(B–F and K–P) Scratches between the first and last scratch are highly stereotyped and follow a similar trajectory during a given bout.

(B, H, and I) Scratches making prolonged contact with the skin show humped peaks in the y position trace (I); this is also reflected in the rapid paw movement away from the skin (B and H).