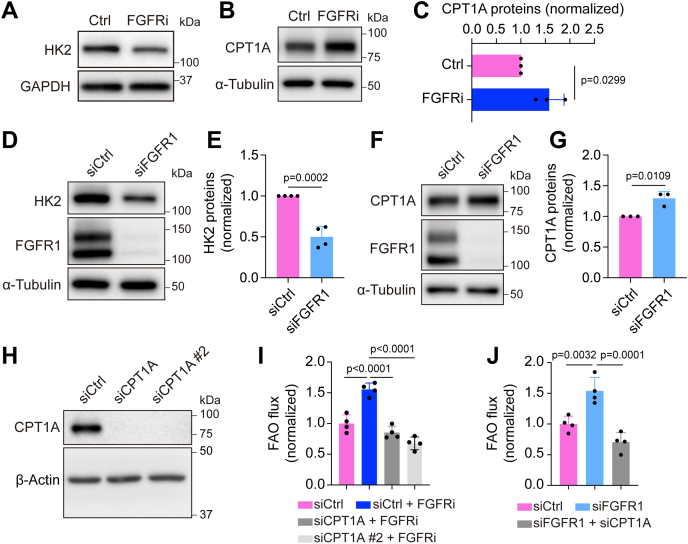

Figure 2.

FGFR blockade increases CPT1A expression for promoting FAO in HDLECs.A, Western blot analysis of HK2 and GAPDH (loading control) in HDLECs treated with vehicle or the FGFR inhibitor ASP5878 for 2 days (representative of three independent experiments). B and C, Western blot analysis (B) and densitometric quantification (n = 3 independent experiments) (C) of CPT1A proteins in HDLECs treated with vehicle or the FGFR inhibitor ASP5878 for 2 days, nd α-tubulin served as a loading control. D and E, Western blot analysis (D) and densitometric quantification (n = 4 independent experiments) of HK2 proteins in HDLECs treated with nontargeting (control) or FGFR1 siRNA. F and G, Western blot analysis (F) and densitometric quantification (n = 3 independent experiments) (G) of CPT1A proteins in HDLECs treated with nontargeting (control) or FGFR1 siRNA. FGFR1 proteins were examined to confirm knockdown efficiency, and α-tubulin served as a loading control. H, Western blot analysis of CPT1A and α-tubulin (loading control) in HDLECs treated with nontargeting (control) or CPT1A siRNA (representative of two independent experiments). I and J, 9,10-3H-palmitic acid–based measurement of FAO flux in HDLECs with the indicated treatments (n = 4 biological replicates). Note that CPT1A silencing normalized FAO flux increase caused by FGFR inhibition (I) or FGFR1 knockdown (J). Data represent mean ± SD; p values were calculated by unpaired t test (C, E, and G) or one-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test (I and J). CPT1A, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A; FAO, fatty acid β-oxidation; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HDLEC, human dermal lymphatic endothelial cell; HK2, hexokinase 2.