Abstract

Introduction

In clinical consultations, men with erectile dysfunction do not always express personal, sexual, and interpersonal concerns.

Aim

We explore whether the attenuated impact of erectile dysfunction may be explained by a regulation of negative affect that causes activation of the attachment system.

Methods

The study sample consisted of 69 men diagnosed with erectile dysfunction, mean (SD) age 56 (10.83) years. Participants completed self-reported questionnaires to assess erectile dysfunction severity, attachment style, sexual satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and psychological symptoms.

Main Outcome Measure

The moderating role of attachment between erectile dysfunction and sexual satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and psychological distress was evaluated using multiple linear regression and moderation analysis.

Results

All men in the sample had high attachment avoidance, distributed between the dismissive-avoidant (69.6%) and fearful-avoidant (30.4%) substyles, but low levels of psychological symptoms. Despite their erectile dysfunction, 27 patients (39.1%) rated their sexual life as satisfactory, and 46 (66.7%) rated their relationship with their partner as satisfactory. Men with fearful-avoidant attachment reported feeling more sexual desire and less sexual satisfaction than men with dismissive-avoidant attachment. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that sexual satisfaction variance was explained by erectile dysfunction severity, attachment anxiety, and relationship satisfaction scores. Moderation analysis showed that attachment anxiety, but not relationship satisfaction, moderated the impact of erectile dysfunction on sexual satisfaction.

Conclusion

The avoidance dimension of attachment, which tends to be high in patients with erectile dysfunction, involves deactivation of the sexual system in an effort to minimize the emotional distress associated with erectile dysfunction, which damages sexual and relationship intimacy and delays the decision to obtain professional help. The presence of high attachment avoidance and the moderating value of attachment anxiety allow us to propose specific treatments for these men.

Maestre-Lorén F, Castillo-Garayoa JA, López-i-Martín X, et al. Psychological Distress in Erectile Dysfunction: The Moderating Role of Attachment. Sex Med 2021;9:100436.

Key Words: Erectile Dysfunction, Attachment, Sexual Satisfaction, Relationship Satisfaction, Psychological Distress

INTRODUCTION

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5),1 erectile dysfunction (ED) is defined as a marked difficulty in obtaining an erection during sexual activity, with symptoms persisting for around 6 months and causing clinical discomfort in the patient. The ED should not be better explained as a nonsexual mental disorder, be the outcome of severe relationship distress or other stressors, or be attributable to substance abuse or medication or a medical condition. Epidemiological studies of sexual problems show that a prevalence of 34.8%-41.6% is greatly reduced to 9.9%-15.1% if we only include men who report distress.2,3 Clinical practice also confirms that the expression and intensity of personal and relationship distress in men with ED is lower than expected; a possible explanation for this attenuated emotional impact of ED might be the regulatory function of negative affect in the attachment system.4, 5, 6, 7

The attachment system is an innate behavioural system that aims to restore security and alleviate distress through proximity to attachment figures.8 Attachment theory, therefore, helps us understand the process of regulation of affect. The greater or lesser availability and sensitivity of attachment figures, and the degree to which they respond or not to a person's needs, shapes a history of relationships that is internalized in the form of mental representations, expectations, emotions, and attitudes associated with intimate relationships. Bowlby9 pointed out that such cognitive-affective representations, called internal working models, reflect information about the self and about others, about the degree to which one is worthy or unworthy of receiving affection, and about whether or not others are reliable and available to offer support and care. In securely attached people, internal working models also configure a facility to regulate emotions. Conversely, people with insecure attachment tend to hyperactivate or deactivate emotions.10, 11, 12

Although attachment is established in the context of the relationship between a child and their caregiver, adults also seek closeness and support when they feel stressed or threatened.13,14 In an adult context, the couple relationship promotes an intense emotional bond and the expectation of being cared for and protected, or, on the contrary, a fear of rejection. Hazan and Shaver15 consequently argue that the couple relationship, including sexual experience, is also an attachment relationship. Unlike childhood attachment, where it is the child who seeks proximity with the adult caregiver, in adult relationships the couple acts reciprocally as each other's attachment figure.

The different attachment styles can be understood as combinations of 2 main dimensions: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance.16,17 Attachment anxiety is associated with the model of the self and with whether the person has mainly positive or negative perceptions of the self, which, in turn, results in a greater or lesser fear of rejection and abandonment. Attachment avoidance is related to the perception of others as unreliable or rejecting, which, in turn, determines whether the person will feel better or worse in a relationship of dependency or intimacy.18,19 A secure attachment style is characterized by low anxiety and low avoidance, by a feeling of security and comfort with proximity and interdependence, and by confidence that the support of the other can be counted on to cope with stress. A preoccupied attachment style (high anxiety and low avoidance) is characterized by an imperative need for closeness and a simultaneous fear of rejection, leading to an insistent search for the attention and care of the other. The avoidant attachment style (low anxiety and high avoidance) reflects an attitude of self-sufficiency and a preference for maintaining emotional distance in relationships, leading to a suppression of attachment needs.16,20 Bartholomew and Horowitz16 identified a fearful-avoidant subtype, characterized by high avoidance and also high anxiety (a subtype labelled dismissive-avoidant that was included with the other avoidant subtypes). People with fearful-avoidant attachment have a negative representation of their partners, which makes empathy and proximity difficult. A key characteristic of this kind of attachment is that a fear of rejection makes it difficult for the person to approach others, while their avoidance is ineffective in eliminating distress, with the result that their psychological wellbeing is affected.12,21

According to attachment theory, the sexual system is another innate behavioural system that governs sexual relations and individual differences in attitudes, behaviours, physiological aspects, motivations, emotions, and cognitive representations of sexuality.4 While the sexual system is independent of the attachment system, both are usually integrated within a relationship. In adulthood, a partnership of 2 or more years of duration constitutes a link in which sexuality is present and in which attachment is activated when one of the partners experiences anxiety or fear; this attachment is reflected in proximity, sought to relieve emotional pain and regain a feeling of security.22, 23, 24 As with the attachment system, the primary strategy of the sexual system is to seek proximity and seduce a partner who is attractive as a way of achieving a pleasurable sexual relationship that reinforces feelings of self-efficacy and the experience of intimacy. However, if, as the primary strategy, the sexual experience is unsatisfactory, and the search for proximity to the partner does not reduce the distress resulting from the threat to the self and the relationship, then secondary strategies to regulate affect will be mobilized, as follows:14,25

-

a)

Hyperactivation, involving excessive emphasis on sex, a hypervigilant attitude regarding the sexual needs of the partner and regarding signs of attraction or rejection, and a risk of coercive attitudes and chronic activation of the sexual system, generating anxiety.

-

b)

Deactivation, involving inhibited sexual desire, sexual excitement and orgasmic pleasure, erotophobia, avoidance of sex, and distancing from the partner when they express interest in sex, with the result that the sexual experience is separated from tenderness and intimacy, leading, in turn, to possible promiscuity with the aim of reinforcing self-image.

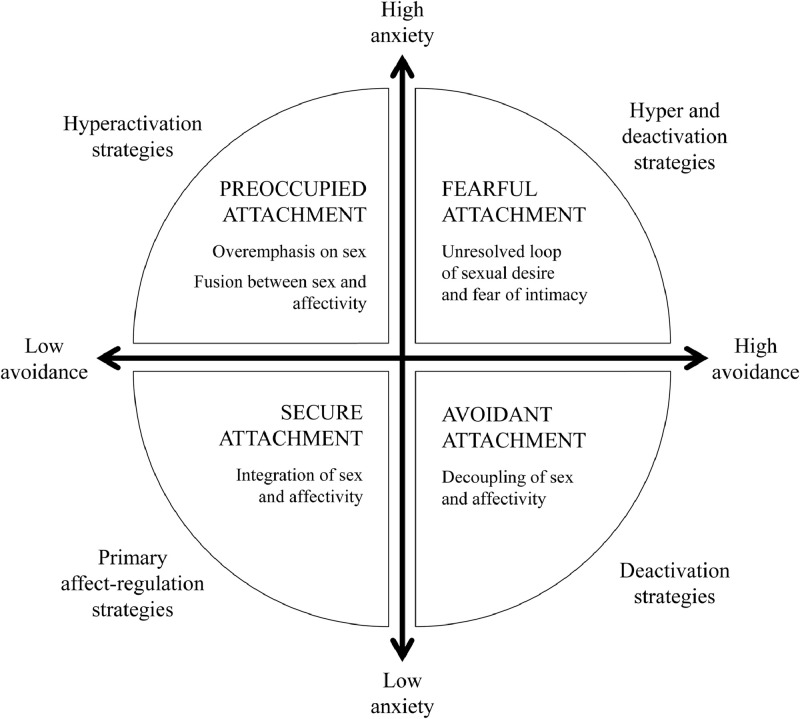

The characteristics of the attachment system will therefore influence the functioning of the sexual system and patterns of sexual behaviour (Figure 1).14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 People with secure attachment easily and harmoniously integrate sex in their relationship. People with preoccupied attachment, on the other hand, tend to confuse sex and love in such a way that sexual relations become a means to satisfy the need for proximity; this explains why these individuals mostly value the affective aspects of sexual experience and why satisfaction (dissatisfaction) with sexual relations is equated with a better (poorer) affective relationship.7,26 People with avoidant attachment tend to decouple sex from affectivity, as they experience intimacy as distressful and use sex as a means to reduce stress, thereby repressing their sexual desire and their receptivity to a partner's sexual and affective needs.5,14

Figure 1.

Attachment styles, the sexual system, and emotional regulation strategies.

The interaction between attachment, sexuality, and relationship quality has broad empirical support.27 On the one hand, although insecure attachment is a risk factor for ED in men,28 a satisfactory sex life can buffer the negative impact on relationship quality29 by enhancing the security of the relationship bond. On the other hand, a person's attachment type leads to sexuality being associated with different relational goals; therefore, if difficulties appear, a different type of emotional regulation is also activated.20 Thus, for men with ED, if attachment is insecure, the attachment system is activated in the form of secondary regulation strategies consisting of hyperactivating or deactivating both the emotions and the sexual system;14 if attachment is fearful, hyperactivation of the sexual system reduces the feeling of sexual inadequacy and mitigates the fear of abandonment, as sexual relations become a way of achieving proximity with the partner; finally, if attachment is avoidant, the sexual system is typically deactivated, with sexual needs suppressed or minimized in order to avoid frustration.4

The differences between attachment styles and their corresponding emotional regulation strategies can increase in stressful circumstances30,31 and influence the intensity of the emotional reactions associated with sexual dysfunction.20,32,33 High attachment avoidance is reported to be prevalent among men with ED,34 suggesting that deactivation of affections predominates, explaining why men with ED tend to underplay their level of discomfort.35

Most studies on the relationship between attachment and sex have been carried out with the general population.26,28 The objective of this study was to evaluate that relationship in a clinical context by investigating associations between attachment, psychological distress, and sexual and relationship satisfaction in men with ED attending the Andrology Service of a Barcelona public health hospital. Bearing in mind the studies reviewed above,26,28 we would expect to find a higher prevalence of avoidant attachment in men with ED. What has not been investigated, to our knowledge, is the prevalence of the Bartholomew and Horowitz16 avoidant attachment subtypes, namely, dismissive-avoidant attachment (high avoidance and low anxiety) and fearful-avoidant attachment (high avoidance and high anxiety). Given that ED limits sexual satisfaction and, consequently, interferes with the protective role of sex in a relationship, we would expect to see negative repercussions for the relationships of the men in our sample. In this context, secondary emotional regulation strategies would be activated in such a way that distress would be moderated, not only by the attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions, but also by the quality of the partnership.26,28,36

The aim of the present study was to answer the following research questions: Is there a high incidence of insecure attachment (high anxiety and/or attachment avoidance) in men diagnosed with ED? Does anxiety and/or attachment avoidance moderate the relationship between ED and sexual distress, relationship distress, and psychological distress? We hypothesized that:

-

1.

The incidence of insecure attachment (high anxiety and/or attachment avoidance) is high in men diagnosed with ED.

-

2.

Anxiety and/or attachment avoidance moderates the relationship between ED and sexual satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and psychological distress.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

Our sample was composed of 69 men diagnosed with psychogenic ED, consulting for the first time at the Andrology Department of a Barcelona public health hospital. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) ED diagnosis according to DSM-5;1 (ii) mild, moderate, or severe ED according to the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF); (iii) absence of any physical illness or psychiatric disorder that might cause ED; and (iv) men in a stable relationship with a partner (of 2 or more years’ duration). As for exclusion criteria, these were: (i) ED with no spontaneous erections according to the nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity test (NPTR); (ii) men with a penile implant; and (iii) men who had undergone a prostatectomy.

Procedure

Patients attended the Andrology Department for a semi-structured interview and physical examination; when necessary, to exclude organic ED, the patient underwent an NPTR test, neurological examination, penile duplex doppler ultrasound, and hormonal assessment. To rule out other psychiatric disorders, an experienced psychologist evaluated patients according to DSM-51 criteria. The study sample was recruited before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants were informed about the objective of the study, signed the informed consent, and completed a set of psychometric evaluation instruments (described in detail below). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital.

Measures

Sexual function was measured using the IEFF37 (validated Spanish version38). This self-administered Likert-scored 15-item scale identifies problems in the sexual response domains of sexual desire, erectile function, orgasmic function, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction, that is, satisfaction with sexual life in general and with sexual relations with a partner. The overall test score ranges from 5 to 75, with lower scores indicating greater dysfunction and greater dissatisfaction. In the erection domain, scores range from 1 to 30, with ED severity cut-off points for the Spanish population of 6–10 (severe), 11–16 (moderate), 17–25 (mild), and 26–30 (none). Internal consistency among the different domains is above α = 0.73 (overall test α = 0.90).

Attachment was measured using the Spanish version18 of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) instrument,39 a self-administered scale of 36 items, 18 each evaluating the anxiety and avoidance dimensions of attachment (distress occasioned by fear of rejection and abandonment, and distress generated by proximity and dependence on others, respectively). Satisfactory internal consistency has been demonstrated for this instrument for both the avoidance (α = 0.87) and anxiety (α = 0.85) dimensions. Dimensional evaluation of the ECR, based on combining the 2 dimensions of anxiety and avoidance, reflects 4 attachment styles: secure, preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, and fearful-avoidant.

Psychological distress was evaluated using Symptom Checklist 90 Revised (SCL-90-R),40 in its Spanish validated version.41 This self-administered scale is composed of 90 items that evaluate 9 dimensions of distress: somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism. To generate an overall measure of psychological distress, based on the number and intensity of symptoms in the patient, we used the General Severity Index (GSI) from the SCL-90-R (α = 0.97).

Sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction were measured using the Spanish versions42 of the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX) and the Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction (GMREL),35 respectively, both subscales of the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction (IEMSS).43 The GMSEX (α = 0.92) and GMREL (α = 0.94) instruments are each composed of 5 Likert-scored (5–35) items, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were computed to describe sample characteristics. Paired-sample Mann-Whitney U tests were used to examine mean differences between dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant patient groups (those who scored lower and higher attachment anxiety scores, respectively). Pearson correlations were computed to test the pattern of associations between attachment, psychological distress, sexual and relationship satisfaction, sexual function, age, and ED duration. The impact of the measured variables on sexual satisfaction were further evaluated using multiple linear regression and moderation analysis. The regression analysis was performed considering sexual satisfaction as the dependent variable, and ED, attachment anxiety and avoidance, relationship satisfaction, and psychological distress as predictors. The moderation analysis was performed to assess the roles played by anxiety and relationship satisfaction in the link between ED and sexual satisfaction (as the outcome). Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

As can be seen in Table 1, the mean (SD) age of the patients was 56.07 (10.83) years, and mean (SD) duration of ED before consultation was 4.9 (6.5) years. All patients were in stable heterosexual relationships. Men who were employed (56.5%) or who were retired (24.6%) predominated, and most had secondary (47.8%) or primary (24.6%) studies. Regarding toxic habits, 29% of the men regularly consumed alcohol and 24.6% were smokers. Most patients (88.4%) had health issues, and 68.1% were on medication, mostly antihypertensives (33.3%) and statins as treatment for cholesterol (34.8%). Examination confirmed that none of the physical health problems were causes of the ED. Around a third (29.0%) of the men reported having experienced psychological distress, although in no case did this imply their having a psychological disorder.

Table 1.

Patient sociodemographic characteristics (n = 69)

| Characteristics | Men |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| Mean (SD) | 56.07 (10.83) |

| Median (range) | 57.50 (30-76) |

| ED duration (y) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (6.5) |

| Median (range) | 2 (0.3-30) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Primary | 17 (24.6) |

| Secondary | 33 (47.8) |

| Tertiary | 18 (26.1) |

| Occupational status, n (%) | |

| Employed | 39 (56.5) |

| Unemployed | 7 (10.1) |

| Retired | 17 (24.6) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |

| Single | 0 (0) |

| Partnered | 69 (100) |

| Children, n (%) | |

| Yes | 53 (76.8) |

| No | 14 (20.3) |

| Toxic habits, n (%) | |

| Alcohol | 20 (29) |

| Smoking | 17 (24.6) |

| Main health problems, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 28 (40.6) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 29 (42.0) |

| Psychological distress | 20 (29.0) |

| Diabetes | 14 (20.3) |

| Joint disorders | 17 (24.6) |

| Main medications, n (%) | |

| Antihypertensives | 23 (33.3) |

| Statins | 24 (34.8) |

Of the 69 men in the sample, over half (n = 38; 55.07%) experienced severe ED, while 16 (23.19%) and 15 (21.74%) had moderate and mild ED, respectively. Regarding the GMSEX, 27 patients (39.1%) rated their sexual life as satisfactory, while according to the GMREL, 46 (66.7%) rated their relationship as satisfactory. According to the GSI, 41 patients (59.42%) presented higher overall scores for psychological distress than the general population, although only 3 patients (4.4%) achieved a higher score than the average for the psychiatric population.

The Role of Attachment

The mean (SD) values for attachment anxiety and for attachment avoidance were 3.54 and 3.95, respectively. All the patients had a higher than normal avoidance score, while 48 patients (69.6%) had a lower than normal anxiety score. From the point of view of attachment typologies (Figure 1), 69.6% of the sample tended towards dismissive-avoidant attachment (high avoidance and low anxiety), and the remaining 30.4% tended towards fearful-avoidant attachment (high avoidance and high anxiety).

Table 2, which compares dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant (lower and higher scores for attachment anxiety, respectively) patient groups, shows that the latter presented with greater attachment avoidance and greater sexual desire. However, relationship satisfaction (according to the GMREL) was higher in patients with dismissive-avoidant attachment than in patients with fearful-avoidant attachment.

Table 2.

Comparison between fearful-avoidant attachment and dismissive-avoidant attachment groups

| Dismissive-avoidant (n = 48) |

Fearful-avoidant (n = 21) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | P |

| Age | 55.60 | 10.89 | 57.14 | 10.90 | 436.0 | .445 |

| ED duration | 4.82 | 6.53 | 5.00 | 6.70 | 345.0 | .497 |

| Attachment avoidance | 3.78 | 0.44 | 4.31 | 0.58 | 220.0 | <.001† |

| GSI | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 405.0 | .197 |

| GMSEX | 21.14 | 10.42 | 16.32 | 8.90 | 286.5 | .079 |

| GMREL | 29.60 | 6.24 | 24.65 | 8.92 | 248.5 | .017* |

| IIEF | 31.27 | 17.28 | 33.76 | 16.43 | 451.0 | .489 |

| - Erectile function | 10.50 | 7.66 | 11.71 | 7.18 | 444.5 | .436 |

| - Orgasmic function | 5.42 | 3.70 | 5.00 | 3.73 | 472.5 | .678 |

| - Intercourse satisfaction | 5.25 | 3.91 | 5.48 | 3.84 | 485.5 | .807 |

| - Sexual desire | 5.23 | 2.10 | 6.90 | 2.10 | 291.5 | .005* |

| - Overall satisfaction | 4.87 | 2.57 | 4.67 | 2.13 | 500.5 | .963 |

P < .05,

P < .01.

U refers to the Mann-Whitney U test. ED = erectile dysfunction; GMREL = Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction; GMSEX = Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction; GSI = General Severity Index (from the Symptom Checklist 90 Revised); IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function.

Attachment, Psychological Distress, and Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction

The age of the patients negatively correlated with the overall IIEF score and the erectile function and orgasmic function scores (Table 3). Sexual satisfaction (GMSEX) correlated positively with relationship satisfaction (GMREL), and correlated negatively with the anxiety dimension of attachment; it correlated positively with the IIEF overall score, and, except for the sexual desire subscale, with the erectile function, orgasmic function, and intercourse satisfaction subscale scores. All GMSEX correlation values were moderate (between –.280 and.606). The attachment avoidance and anxiety dimensions correlated positively and moderately with each other, while correlation with psychological distress (GSI) was low.

Table 3.

Means, SDs and correlations between the variables of interest

| Measure | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 56.07 (10.83) | ||||||||||||

| 2. ED duration | 4.87 (6.53) | .16 | |||||||||||

| 3. Avoidance | 3.95 (0.54) | .10 | .09 | ||||||||||

| 4. Anxiety | 3.54 (0.99) | .14 | .02 | .56† | |||||||||

| 5. GSI | 0.63 (0.44) | -.01 | -.09 | .19 | ,30* | ||||||||

| 6. GMSEX | 4.10 (1.93) | -,11 | -.03 | -.22 | -.28* | -.14 | |||||||

| 7. GMREL | 5.73 (1.34) | -.06 | -.01 | -.09 | -.19 | -.09 | .37† | ||||||

| 8. IIEF | 32.03 (16.95) | -.18 | .06 | -.11 | -.02 | -.03 | .47† | -.04 | |||||

| 9. Erectile function | 10.87 (7.49) | -.23 | .02 | -.12 | .04 | -.08 | .36† | -.05 | .93† | ||||

| 10. Orgasmic function | 5.29 (3.68) | -.19 | .20 | -.12 | -.11 | .00 | .41† | -.05 | .88† | .73† | |||

| 11. Intercourse satisfaction | 5.32 (3.86) | -.11 | .05 | -.16 | -.03 | -.04 | .51† | .02 | .93† | .83† | .79† | ||

| 12. Sexual desire | 5.74 (2.22) | -.04 | -.08 | .21 | .37† | .07 | .14 | -.17 | .51† | .38† | .38† | .37† | |

| 13. Overall satisfaction | 4.81 (2.43) | -.07 | .03 | -.13 | -.09 | .01 | .61† | .10 | .82† | .66† | .74† | .82† | .34† |

P < .05,

P < .01.

ED = erectile dysfunction; GMREL = Global Measure of Relationship Satisfaction; GMSEX = Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction; GSI = General Severity Index (from the Symptom Checklist 90 Revised); IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function.

Sexual Satisfaction Regression

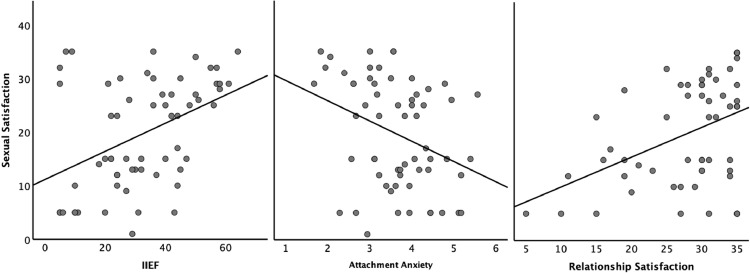

A multiple linear regression analysis was performed considering sexual satisfaction as the dependent variable (R2 = 0.484, Adj-R2 = 0.434; F(5.52) = 9.739; P < .001). Results showed that sexual satisfaction variance was a function of the overall IIEF (βstd = 0.469; P < .001), attachment anxiety (βstd = –0.300; P = .018), and relationship satisfaction (βstd = 0.364; P = .002) scores. In other words, greater sexual satisfaction was a function of less severe ED (higher IIEF scores), lower attachment anxiety, and greater satisfaction with the partner relationship (Figure 2). Excluded from the model were the attachment avoidance variable and the GSI (both P > .05).

Figure 2.

Regression analysis results showing that greater sexual satisfaction is a function of less severe ED, lower attachment anxiety, and greater relationship satisfaction.

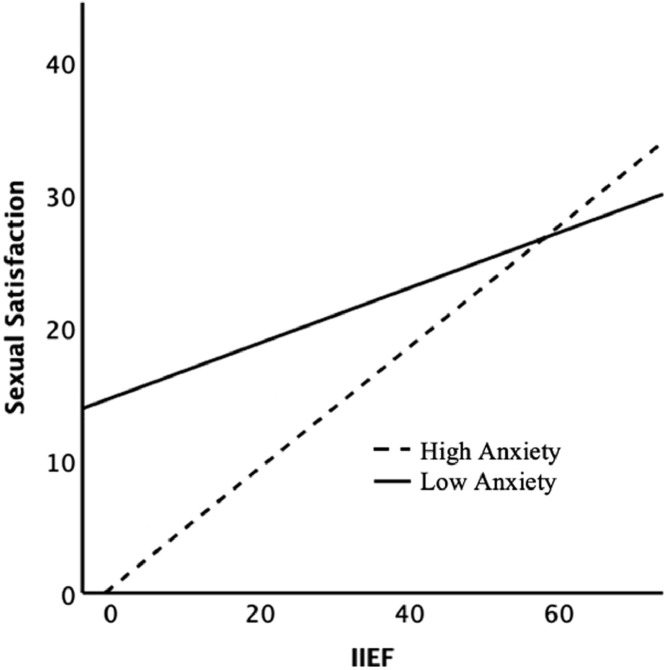

Sexual Satisfaction Moderators

To further assess whether the association between sexual satisfaction and ED severity was moderated by anxiety or relationship satisfaction, a moderation analysis was performed using the sexual satisfaction score as the outcome, the overall IIEF score as the predictor, and, as moderators, anxiety and relationship satisfaction dichotomized according to ECR18 and GMREL42 mean scores. The model results (R2 = 0.445, Adj-R2= 0.392; F(5.52) = 8.337; P < .001) pointed to significant interaction for IIEF*attachment anxiety (P = .032) but not for IIEF*relationship satisfaction (P = .270) (see Table 4 and Figure 3).

Table 4.

Moderation model scores

| 95% CI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | βstd | t | P | Lower | Upper | |

| (Intercept) | 8.797 | 11.98 | 0.734 | .466 | -15.25 | 32.85 | |

| IIEF | 0.221 | 0.344 | 0.380 | 0.643 | .523 | -0.469 | 0.911 |

| Attachment anxiety | -15.89 | 4.972 | -0.766 | -3.198 | .002† | -25.87 | -5.923 |

| Relationship satisfaction | 12.60 | 5.667 | 0.567 | 2.224 | .030* | 1.234 | 23.97 |

| IIEF*attachment anxiety | 0.294 | 0.133 | 0.885 | 2.206 | .032* | 0.027 | 0.561 |

| IIEF*relation. satisfaction | -0.173 | 0.155 | -.567 | -0.597 | .270 | -0.485 | 0.139 |

P < .05,

P < .01.

IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function.

Figure 3.

Sexual satisfaction and erectile function (International Index of Erectile Function, IIEF). Linear fits for high-anxiety (βstd = 0.876) and low-anxiety (βstd = 0.306) men.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to evaluate the moderating role of attachment on the distress associated with ED. The results obtained for our sample of 69 men – over half with severe ED, of longstanding duration (around 5 years) – reveal that they all had insecure attachment (confirming our first hypothesis) and that their psychological wellbeing, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction was maintained. Around a third of the patients considered their sexual life to be satisfactory, while more than half reported also being satisfied with their relationship with their partner. Although a relationship was observed between sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction, also reflected in other studies,44, 45, 46 the latter was not associated with the overall IIEF score or with any of its subscale scores. While psychological distress was present, in very few of the evaluated men did it achieve clinically significant levels.

Our findings may be explained by the role played by attachment in regulating emotional distress.12 ED may lead to a feeling of insecurity in relation to sexual intimacy, and to activation of the attachment system, whereby each man makes an assessment regarding his partner's availability to help deal with that insecurity. The attachment avoidance dimension reflects the degree of mistrust regarding a partner and the need to resort to deactivation as a secondary strategy to regulate affect, while the attachment anxiety dimension reflects the degree of concern about the partner's availability and the need for greater proximity as a strategy to regulate affect.

In the 69 patients evaluated in our study, attachment avoidance in particular was high, corroborating other studies that report that attachment avoidance is frequent in men with ED;34,47 in contrast, women with sexual problems typically experience high anxiety.35 Men with ED tend to regulate sexual, relationship, and psychological distress by deactivating the sexual system;12 a high level of attachment avoidance would reflect the attempt to deny emotional pain and dissociation from sexual problems.. ED is experienced as something foreign to both the individual's personality and their relationship with a partner. Men with ED therefore strive to play down both their sexual problems and the possible impact on themselves and their relationship, which, in turn, may explain why men allow around 2 years to elapse before seeking professional help for their ED. Dissociation may initially attenuate the sexual distress and safeguard satisfaction with the partner relationship, but it may also aggravate the loss of sexual potency associated with ED and lead to delayed consultation.34,48

In our study, the attachment anxiety dimension correlated negatively with sexual satisfaction and positively with sexual desire and psychological distress. The greater the fear of rejection and abandonment, therefore, the more sexual relations with the partner are sought, yet the difficulties generated by ED result in greater frustration and emotional pain.27,49

Considering both dimensions of attachment together (according to the Bartholomew and Horowitz16 model), just over 2 thirds of our patients with ED had characteristics of a dismissive-avoidant attachment style (high avoidance and low anxiety), while the remaining third experienced a fearful-avoidant attachment style (high avoidance and high anxiety). We consider this finding to be one of the contributions of our research, since it identifies a subgroup of patients with ED who experience both high avoidance and high anxiety. In this fearful-avoidant attachment subgroup, the secondary deactivation strategy hinders expression and fails to significantly reduce distress, resulting in ongoing latent suffering. This characteristic in men with ED and fearful-avoidant attachment has important implications for clinical interventions, as indicated below.

The multiple linear regression analysis confirmed the sexual satisfaction association with attachment style, relationship satisfaction, and ED severity. Specifically, greater sexual satisfaction is linked to less severe ED, lower attachment anxiety, and greater relationship satisfaction. Moderation analysis further highlighted this association, showing that anxiety plays a significant role in the link between ED and sexual satisfaction (thereby confirming our second hypothesis). A greater fearful-avoidant attachment score was associated with both poorer sexual satisfaction and poorer relationship satisfaction. Sexual satisfaction was better preserved in men with dismissive-avoidant attachment, while their relationship satisfaction was comparable to that of the general population.

Although the results discussed so far suggest that attachment avoidance played an important role in our patients with ED (recall that all patients in our sample had high avoidance levels), attachment avoidance was not a significant variable in the regression analysis. This is explained, not only by the high avoidance levels, but also by the fact that there was not enough variability in relation to this dimension in our sample to be able to detect statistically significant results in the regression analysis. Also meriting consideration is the fact that the role played by sexual activity in relationships is diverse: while for some couples it is crucial, for others it may be secondary.6

We suggest that the results of our study have important clinical implications. Our findings underline the importance of evaluating the role played by sexual activity in the partnerships of men who consult for ED. Affective needs associated with sexual intercourse should also be considered, along with the deactivation strategies by which the distress that may be caused by ED is regulated. In a stable partnership, sexual intercourse meets needs that are not strictly sexual,4 so the general objective of interventions should be to reduce the perception that ED poses a serious threat to both the self and the relationship with a partner. To re-establish intimacy in a relationship, clinical work should therefore focus on clarifying 2 issues: how the man assesses the availability of his partner, and the strategy the man uses to regulate the negative affect activated by ED. It is also important to understand what triggered the request for professional help, as well as the patient's awareness of ED and their underlying unexpressed emotional pain.

Treatment strategies need to be considered from a biopsychosocial perspective. For patients with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style, the psychotherapeutic focus needs to be on the dissociated and avoided emotions. Efforts should therefore focus on awareness and improved management of emotions, so as to reduce distancing and increase sexual and relationship intimacy. For patients with a fearful-avoidant attachment style, the focus needs to be on representations of the self and others, on negative self-perceptions, and on fears of rejection.

Whenever possible, type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE5) inhibitors can be used to alleviate sexual symptoms and facilitate a recovery of confidence in sexual capacity. Including the partner in treatment can also help modify certain beliefs about what is sexually expected of the patient, which, in turn, will alleviate the fear that sexual difficulties will damage the relationship and lead to abandonment. In general, what is observed in clinical care is that sexual problems are ultimately an expression of intrapersonal and/or interpersonal conflicts.

One of the limitations of our study is its transversal nature, which prevents us from understanding how ED in our patients evolves over time and what the possible causal implications of our results could be. The size of our sample weakens the statistical power of the study, not to mention limiting the statistical procedures that could be applied. These issues may affect the stability of our results, the variables that interact with each other, and the kind of interactions between variables; for instance, the fact that attachment avoidance is not significant in our models may be due to this limitation. Likewise, in our study we have proposed that attachment moderates the relationship between ED and sexual satisfaction, although other models of interaction between the variables could be formulated; for instance, lower sexual and/or relationship satisfaction might increase the likelihood of ED in men with a certain type of attachment.

Our findings, furthermore, may be distorted by sample recruitment from a single health centre, the wide age range of the patients, the time elapsed between ED onset and the first consultation, and the fact that self-reporting typically involves biases and also prevents understanding of the personal significance of a response. Finally, while all the men in the sample had been in a relationship for more than 2 years, the precise duration of their relationships was not determined, so this could be an important issue to consider in future studies.

Future studies carried out in other healthcare settings are needed to replicate our finding – in our judgement surprising – that men with ED tend to have high levels of attachment avoidance. It would undoubtedly be interesting to consider sexual functioning from a broader perspective than just sexual response, and to use interviews and a qualitative methodology to explore the ED experience and its impact on the person and their relationship. Other aspects not covered by our study should also be considered, such as a more detailed comparison of men with ED experiencing greater versus lesser sexual satisfaction, and the impact of comorbidities and other stressors that may affect sexual function. Including partners in studies of men with ED and considering their possible sexual problems, attachment styles, and perceptions of a relationship would also enrich the results.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this research throw light on how ED affects psychological, sexual, and relationship functioning, providing insights to treatment strategies aimed at re-establishing security in sexual intimacy that focus on emotions (dismissive-avoidant attachment) and on representations of the self and others (fearful-avoidant attachment).

Most studies on sexual satisfaction and attachment have been conducted with young students with no clinically significant sexual problems. One of the contributions of our study is that it evaluates patients with ED who consult a specialist service. The results point to the importance of attachment as a moderating factor in the psychological and interpersonal impact of ED, which, in turn, yields important insights into ED diagnosis and treatment.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

Conceptualization, F.M.L. and J.C.G.; Methodology, J.C.G., A.A., and I.C.; Investigation, F.M.L. and J.S.; Formal Analysis, I.C. and X.L.M.; Writing – Original Draft, F.M.L. and J.C.G; Writing – Review & Editing, F.M.L., J.C.G., X.L.M., J.S., and I.C.; Visualization, X.L.M., A.A., and I.C.; Supervision, F.M.L. and J.C.G.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrickx L, Gijs L, Enzlin P. Age-related prevalence rates of sexual difficulties, sexual dysfunctions and sexual distress in heterosexual men: Results from an online survey in Flanders. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2019;34:440–461. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell KR, Mercer CH, Ploubidis GB. Sexual function in Britain: Findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) Lancet. 2013;382:1817–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum GE, Mikulincer M, Szepsenwol O. When sex goes wrong: A behavioral systems perspective on individual differences in sexual attitudes, motives, feelings, and behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:822–842. doi: 10.1037/a0036021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis D, Shaver PR, Vernon ML. Attachment style and subjective motivations for sex. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:1076–1090. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprecher S, Cate RM. In: Handbook of sexuality in close relationships. Harvey JH, Wenzel A, Sprecher S, editors. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. Sexual satisfaction and sexual expression as predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson KR, Ahrold TK, Meston CM. The association between sexual motives and sexual satisfaction: Gender differences and categorical comparisons. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:607–618. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9674-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowlby J. Vol. 1. Basic Books; New York: 1969. (Attachment and loss: Attachment). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bretherton I. Updating the ‘internal working model’ construct: some reflections. Attach Hum Dev. 1999;1:343–357. doi: 10.1080/14616739900134191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins NL, Ford MB, Guichard AC. Working models of attachment and attribution processes in intimate relationships. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32:201–219. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraley RC, Garner JP, Shaver PR. Adult attachment and the defensive regulation of attention and memory: examining the role of preemptive and postemptive defensive processes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:816–826. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology; vol. 35. New York: Academic Press; 2003. p. 53–152

- 13.Hazan C, Zeifman D. Sex and the psychological tether. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships, vol. 5. Attachment processes in adulthood. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1994. p. 151–178

- 14.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. A behavioral systems perspective on the psychodynamics of attachment and sexuality. In: Diamond D, Blatt SJ, Lichtenberg JD, editors. Psychoanalytic inquiry book series: vol. 21. Attachment and sexuality. New York: Erlbaum; 2007. p. 51–78

- 15.Hazan C, Shaver PA. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. In: Attachment theory and close relationships. Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso AI, Balluerka N, Shaver PR. A Spanish version of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) adult attachment questionnaire. Pers Relatsh. 2007;14:45–63. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment theory and emotions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment-related dynamics of emotional reactions to relational events. Pers Relatsh. 2005;12:149–168. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewitte M. Different perspectives on the sex-attachment link: Towards an emotion-motivational account. J Sex Res. 2012;49:105–124. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.576351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Fearful-avoidance, disorganization, and multiple working models: Some directions for future theory and research. Attach Hum Dev. 2002;4:223–229. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazan C, Campa M, Gur-Yaish N. In: Dynamics of romantic love: Attachment, caregiving, and sex. Mikulincer M, Goodman GS, editors. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. What is adult attachment; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazan C, Shaver PR. Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychol Inq. 1994;5:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaver P, Hazan C, Bradshaw D. In: The psychology of love. Sternberg RJ, Barnes ML, editors. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1988. Love as attachment; pp. 68–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. In: The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Vangelisti AL, Perlman D, editors. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2006. Attachment theory, individual psychodynamics, and relationship functioning; pp. 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butzer B, Campbell L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Pers Relatsh. 2008;15:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birnbaum GE. In: Attachment theory and research: New directions and emerging themes. Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Guilford Press; New York: 2015. On the convergence of sexual urges and emotional bonds: The interplay of the sexual and attachment systems during relationship development; pp. 170–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefanou C, McCabe MP. Adult attachment and sexual functioning: A review of past research. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2499–2507. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little KC, McNulty JK, Russell VM. Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36:484–498. doi: 10.1177/0146167209352494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feeney JA, Noller P. In: The handbook of sexuality in close relationships. Harvey J, Wenzel A, Sprecher S, editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New Jersey: 2004. Attachment and sexuality and close relationships; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikulincer M, Florian V. In: Attachment theory and close relationships. Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. The relationship between adult attachment styles and emotional and cognitive reactions to stressful events; pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Impett EA, Gordon AM, Strachman A. Attachment and daily sexual goals: A study of dating couples. Pers Relatsh. 2008;15:375–390. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciocca G, Limoncin E, Di Tommaso S. Attachment styles and sexual dysfunctions: A case-control study of female and male sexuality. Int J Impot Res. 2015;27:81–85. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2014.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephenson KR, Meston CM. Differentiating components of sexual well-being in women: Are sexual satisfaction and sexual distress independent constructs? J Sex Med. 2010;7:2458–2468. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis D, Shaver PR, Widaman KF. I can't get no satisfaction”: Insecure attachment, inhibited sexual communication, and sexual dissatisfaction. Pers Relatsh. 2006;13:465–483. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bobes García J. Banco de instrumentos básicos para la práctica de la psiquiatría clínica. Barcelona: Ars Médica. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Derogatis LR. Clinical Psychometric Research; Baltimore: 1975. Brief symptom inventory. [Google Scholar]

- 41.González de Rivera JL, Derogatis LR, de las Cuevas C. The Spanish version of the SCL-90-R. Normative data in the general population. Towson: Clin Psychometric Res. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez-Fuentes M del M, Santos-Iglesias P, Byers ES. Validation of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction questionnaire in a Spanish sample. J Sex Res. 2015;52:1028–1041. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.989307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrance KA, Byers ES. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Pers Relatsh. 1995;2:267–285. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pascoal PM, Byers ES, Alvarez MJ. A dyadic approach to understanding the link between sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual couples. J Sex Res. 2018;55:1155–1166. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1373267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooghe M. Is sexual well-being part of subjective well-being? An empirical analysis of Belgian (Flemish) survey data using an extended well-being scale. J Sex Res. 2012;49:264–273. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.551791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sánchez-Fuentes M del M, Santos-Iglesias P, Sierra JC. A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2014;141:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Giudice M. Sex differences in attachment styles. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;25:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Berant E. An attachment perspective on therapeutic processes and outcomes. J Pers. 2013;81:606–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Pereg D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: the dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motiv Emot. 2003;27:77–102. [Google Scholar]