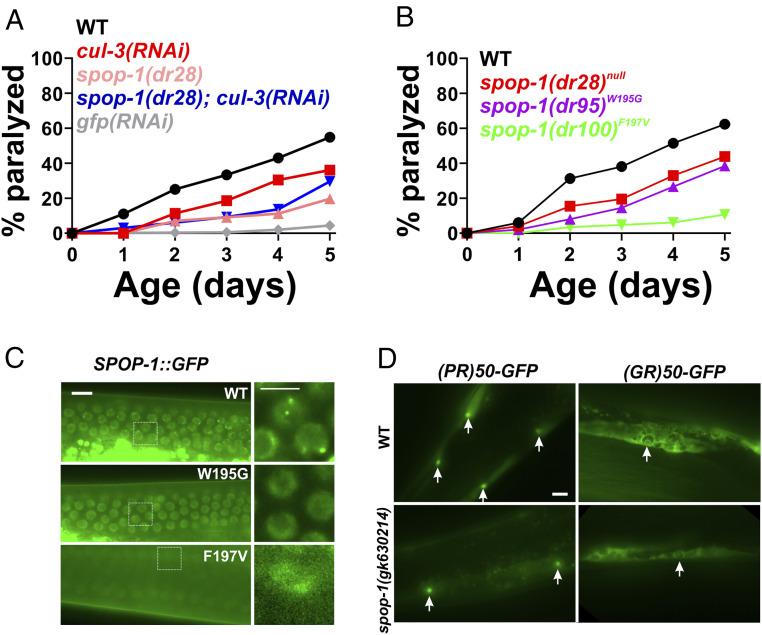

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of a spop-1-cul-3 pathway protects against DPR toxicity without altering DPR levels or localization. (A) PR50 paralysis assay in the indicated genetic backgrounds. n = 100 animals per genotype. WT versus cul-3(RNAi), P = 0.0153; WT versus spop-1(dr28), P = 0.00000036; spop-1(dr28) versus spop-1(dr28); cul-3(RNAi), P = 0.4278. Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. (B) PR50 paralysis assay in the indicated spop-1 genotypes. Mutations were introduced into the endogenous C. elegans spop-1 gene via CRISPR/Cas9. n = 100 animals per genotype. WT versus spop-1(dr28), P = 0.0059; WT versus spop-1(dr95), P = 0.0002; WT versus spop-1(dr100), P = 0.002. Log-rank test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. (C) Localization of a CRISPR-engineered SPOP-1-GFP fusion protein containing the indicated point mutations. Germline nuclei are shown because their high density facilitates observation of multiple instances of SPOP-1-GFP speckling. Similar speckling behavior is observed in somatic cells. (Scale bar, 10 microns.) Arrows in WT point to examples of SPOP-1-GFP nuclear localization exhibiting subnuclear speckles. (D) PR50-GFP and GR50-GFP expression in wild type or spop-1(gk630214). Images are exposure matched. Arrows point to muscle nuclei with nucleolar DPR enrichment, as was previously described for PR50-GFP and GR50-GFP localization in C. elegans (21). (Scale bar, 10 microns.)