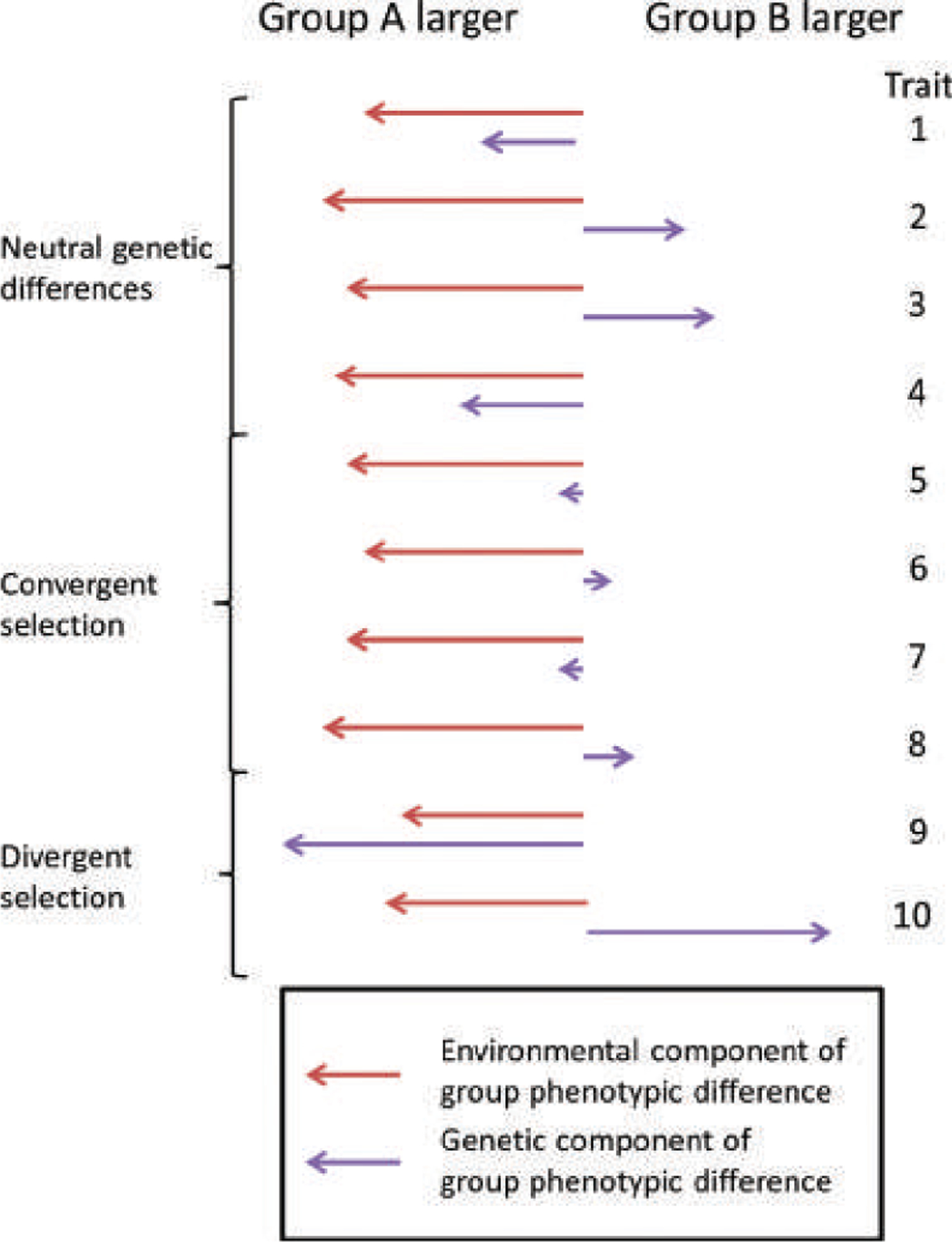

FIGURE 6.

A schematic for thinking about health differences between socially defined racial groups in the United States. Groups such as African Americans face environmental differences likely to lead to worse health outcomes across a range of different diseases (red arrows). For health phenotypes that have been selectively neutral, genetic differences between groups will be random in direction and comparable in size to genetic differences at a single locus—modest for humans, but usually not zero, depending on the groups being considered (purple arrows in traits 1–4). For health phenotypes under convergent selection, such as those that lead to reduced reproductive success in most or all human environments, genetic differences will be random in direction and smaller than for neutral phenotypes (purple arrows in traits 5–8). Some health outcomes, such as skin cancer and sickle-cell disease, differ between groups in part because of divergent selection. (These differences do not necessarily coincide neatly with socially relevant racial divisions.) For such phenotypes, the genetic component of a group difference in phenotype can be large (purple arrows in traits 9 and 10). Not considered in this simple diagram are gene–environment interactions, which often are especially important in cases of divergent selection. For example, in the case of skin cancer, the degree to which genetic variants that lead to darker skin are protective depends on sun exposure.