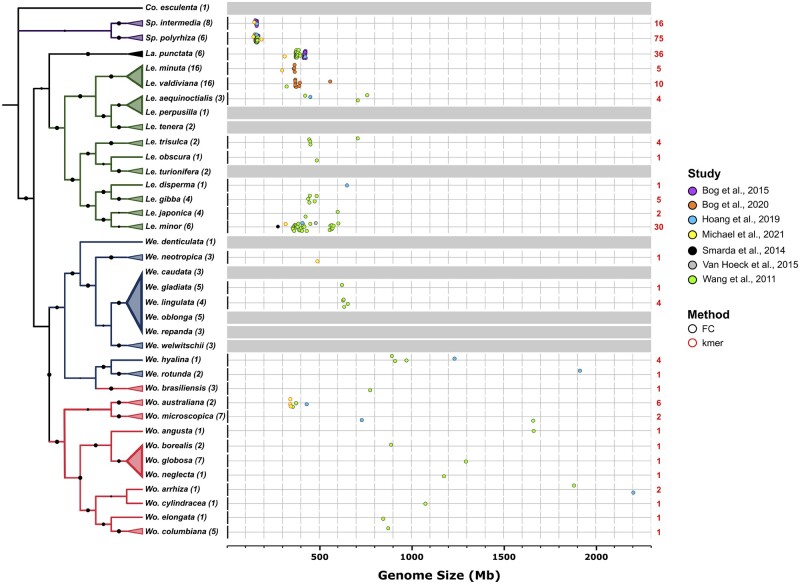

Figure 3.

Phylogeny and variations in genome size of different Lemnaceae species. Left: Evolutionary relationships between Lemnaceae species based on maximum likelihood analysis of concatenated alignment of 139 atpF-atpH and psbK-psbI intergenic spacer sequences from all 36 Lemnaceae species with taro (Colocasia esculenta) as an outgroup. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of clones analyzed. Species that could not be confidently resolved into a single clade were collapsed into a multispecies clade. One interesting observation is that the plastidic barcode sequences of Wo. brasiliensis consistently showed higher similarity to those of We. hyalina and We. rotunda, while morphologically it is distinctly a Wolffia species. This apparent discrepancy could be due to potential hybridization events in the past that resulted in the transfer of plastid genome sequences from a Wolffiella ancestor to a Wolffia lineage. Future genome sequencing of relevant species that may be involved will help clarify this issue. For a detailed methods description, see https://github.com/kenscripts/tpc_dw_review/. Right: The genome sizes for 28 selected species from six groups representing all five genera were estimated using several methods, and in some cases the genome sizes for a significant number of clones from the same species were measured (Sp. polyrhiza, Sp. Intermedia, La. punctata, and Le. minor). Genome size estimates were carried out by flow cytometry (FC, black outline), which requires the inclusion of accurate controls, or by K-mer frequency analysis (kmer, red outline), which relies on high quality short-read sequencing data. Numbers in red depict the number of clones used for each species in genome size estimations. The genome size of We. neotropica was estimated based on K-mer frequency.