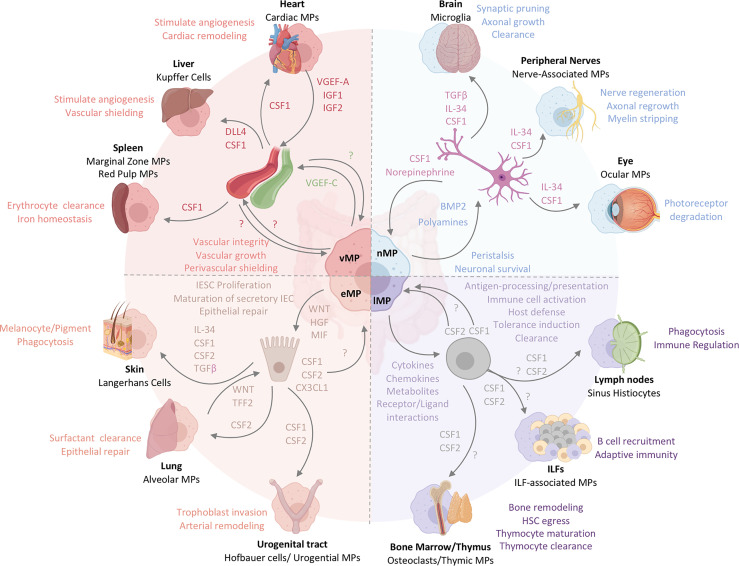

Figure 3.

The functional heterogeneity of intestinal MPs mirrors the multifaceted roles of tissue-resident MPs across organs. Intestinal MPs maintain tissue homeostasis through their interactions with neurons, immune cells, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells. These functions are dependent upon the associations with both immune and non-hematopoietic cells within their respective microenvironments. Released factors and physiological consequences of vasculature-associated MPs (vMPs, red), epithelium-associated MPs (eMPs, light brown), nerve-associated MPs (nMPs, light blue) and lymphoid tissue-associated MPs (lMPs, violet) are indicated by their respective colors. Arrows indicate the source of a given regulator (i.e. produced by MPs perceived by neighboring cell). Nerve-associated MPs in the brain, peripheral nervous system or the eye have specialized functions tailored to their location. These cells depend on neuron-released TGF-β, IL-34 and CSF1. Whether intestinal nMPs require the full spectrum of growth factors is unknown. In addition, a role for maintaining sensory neurons, neuronal growth or synaptic pruning in the gut remains to be shown. Lymphoid tissue-associated MPs are vital in antigen sampling, processing and presentation and mediate dead cell clearance of leukocytes within gut-associated lymphoid tissues. They contribute a plethora of cytokines, chemokines, metabolites and receptor ligands which plays an essential role in host defense against microbes, the orchestration of tolerance induction, and immune cell activation. CSF2, produced by T cells and ILC3s, is essential in facilitating most of these processes in the intestinal tract. It remains to be shown whether CSF1 or other myeloid growth factors like IL-10 support their biological relevance in intestinal immune homeostasis. Peripheral lymph node- and ILF-associated MPs mirror the function of lMPs in the gut, likely due to the similarities in the development and architecture of these organs. The thymus and BM, primary lymphoid tissues, host MPs that mediate tissue remodeling and control the hematopoietic stem cell egress, while also facilitating T cell maturation and clearance. Whether lMPs in the gut are capable of these functions remains to be addressed. The interactions of epithelium and MPs in the gut support IESC proliferation, maturation of secretory IEC and the repair the of damaged epithelial monolayer. CX3CL1 controls the adaptation of an eMPs phenotype but it remains to be shown if CSF1 or CSF2 produced by IECs in the gut contribute to this identity. In contrast to the gut, Keratinocytes, alveolar type 2 cells and urogenital epithelial cells produce distinct combinations of myeloid growth factors that facilitate development and functional specialization of MPs in their respective environments. In the case of the lung, WNT-release by lung macrophages mirrors the mechanism used by intestinal eMPs to facilitate epithelial repair. Functions of eMPs collectively promote tissue homeostasis and tissue remodeling. While the small intestinal lymphatic system is supported by vMPs through the production of VGEF-C to mediate vessel integrity and elongation, molecular mechanisms allowing for a deeper understanding of vMP-blood vessel interactions are currently not known for the intestinal tract. Vasculature-associated MPs surrounding intestinal blood vessel in a symmetric pattern that shields the endothelium from the environment, serving as a cellular firewall for the prevention of microbial spread into neighboring organs. Filter and barrier functions have been assigned to MPs in the spleen and the liver, where these cells are supported by endothelium-derived growth and differentiation factors. Cardiac MPs in fact receive survival signals from the endothelium via the release of CSF1 and in turn support the release of insulin growth factor (IGF) 1 and 2 as well as VGEF-A for cardiac remodeling and angiogenesis.