Abstract

Background:

Several novel treatments of inherited retinal degenerations have undergone phase I/IIa clinical trials with limited sample size, yet investigators must still determine if toxicity or an efficacy signal occurred or if the change was due to test-retest variability (TRV) of the measurement tool.

Materials and Methods:

Synthetic datasets were used to compare three types of TRV estimators under different sample sizes, mean drift, skewness, and number of baseline measurements.

Results:

Mixed effects models underestimated the standard deviation of measurement error (SDEM); the unbiased change score estimator method (UBS) was more accurate. The fixed effect model had less bias and smaller standard deviation than UBS if >2 baseline measurements. The change score estimator had no bias; other estimators introduced bias for lower variability. With sample size <10, all estimators had high variance. With sample size ≥10, the differences between methods were often minimal. The pooled estimator model did not capture drift, whereas a fixed effect regression or mixed effects models accounted for drift while maintaining an accurate measure of variance. With small sample sizes, the bootstrap estimates of SDEM were severe underestimates, while the jackknife estimates were mildly low but much better. The jackknife was more accurate for the unbiased change score method than for the pooled estimator.

Conclusions:

The ideal phase I/IIa study has ≥ 20 subjects and uses UBS or its fixed effect model generalization if >2 baseline measurements. With non-ideal study parameters, investigators should at least quantify the error estimate present in their data analysis.

Keywords: test-retest variability, clinical trials, inherited retinal disease, measurement error

INTRODUCTION

Due to recent advances in gene therapy, there have been an increasing number of phase I/IIa clinical trials for inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs). Although these first-in-human trials are investigating the safety of new therapy, an efficacy signal is sought by investigators and sponsors to catapult their therapy into a pivotal trial. In order to reliably conclude whether there is a change from baseline to post treatment in phase I/IIa trials, investigators and sponsors need to determine test-retest variability (TRV) of their instrument in their specific disease/patient cohort. Therefore, determining whether there is toxicity or an efficacy signal of a specific gene therapy in a phase I/IIa study with no placebo control arm represents a challenge in the IRD field today. Yet, there is no established consensus on how to best calculate TRV and, consequently, to determine toxicity or an efficacy signal above random variation.

There are several methods of calculating TRV. One of the most common methods is determining the coefficient of repeatability (COR),(1) a method popularized by Bland and Altman in 1986(2). In this method, the standard deviation of the differences (SDD) within each subject is multiplied by 1.96 to provide the COR. If a repeat measurement exhibits a change from baseline greater than the COR, then there is evidence of a real change not due to random variability. The SDD divided by √2 is the associated estimate of the standard deviation of measurement error (SDME) of a single measurement. Another method, described by Jeffrey et al. in 2014 (3), estimates the SDME by a weighted average of the standard deviations of the multiple measurements of each subject. Multiplying the SDME by 1.96 (for 95% confidence) and √2 (to account for the difference of two measurements) results in an estimate of COR. The mixed effects model is yet another method to estimate the SDME, which can then be used to provide the COR. Correlation coefficients have also been used for assessing reliability but are a relative(2), rather than absolute, measure of measurement accuracy(4).

We determined the advantages and disadvantages under different experimental parameters of three methods of TRV estimation: a fixed effect regression model (i.e., Bland Altman(2) method), a pooled estimator model (i.e., Jeffrey et al.(3) method), and a mixed effects model. We created synthetic datasets of multifocal ERG measurements to investigate the general properties of the estimators similar to functional measures (e.g., different forms of electroretinography or perimetry) and structural measures (e.g., OCT, fundus autofluorescence) used as outcome measures in IRD clinical trials. The common feature was that the test-retest variability was known by design, and so the estimators could be assessed for bias and precision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Samples

We created synthetic datasets based on mfERG measurements of 48 eyes of 24 patients without retinopathy to guide selection of parameter values for the Monte Carlo simulation. We arbitrarily decided to use mfERG data, though data from other tests of retinal function, such as OCT or ERG, would have also sufficed. There were 2 sets of measurements per patient consisting of 6 ring amplitudes.

Test-Retest Variability Methods

Based on a literature search and expert opinion, we selected three TRV estimation procedures to evaluate. These models included fixed effect regression models (which includes the Bland-Altman(2) method), a similar mixed effects model, and a pooled estimator model (i.e., the Jeffrey et al.(3) method). Details on these estimation procedures are given in the appendix. The estimation procedures were compared to each other on the basis of bias and variance, which are also defined in the appendix.

Monte Carlo Simulations

Although some exact analytic results can be derived, for consistency we assessed the performance of all estimators in Monte Carlo simulations. We varied five factors including sample size, number of baseline measurements per person, measurement drift between visits, inter-subject variability, and error distribution (normal, heavy-tailed, or skewed). Inter-subject variability is defined as the natural variation in measurements between subjects due to known and unknown factors. Additionally, for a selection of simulated datasets, jackknife and bootstrap estimates were computed for each estimator.

1000 datasets were generated under an array of conditions and each TRV estimator was computed. In each case the true SDME was fixed at σ = 1 unit. Samples sizes used were 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, 50, and 75. Systematic drift was either absent (α2 = α1) or present (α2 − α1 = 1 unit). Drift is defined as a change in the average (mean) response over time; it is a form of within-subject change, in contrast to the between-subjects or inter-subject variability defined above. The heterogeneity among subjects was varied from none (σμ = 0, complete patient homogeneity, intra-class correlation (ICC) equal to 0) to high (σμ = 4, ICC>0.9). Measurement error was assumed to be from a normal distribution, from a heavy-tailed distribution, or from a skewed distribution.

Simulations

- Simulation A - investigated the effect the heterogeneity of the subjects has on the different estimators. The relative heterogeneity of a sample is often quantified by the ICC,

which compares the variability of the subjects () and the variability of the measurement (σ2). Low heterogeneity between subjects (i.e., a homogenous sample population) might be encountered in a clinical trial with tight inclusion criteria, such as in trials involving patients who are only on the severe end of a disease spectrum and have less function or other outcome measures to lose in a phase I/IIa trial. High heterogeneity is more likely in a study of a general population. Simulation B – investigated the effect of using more baseline observations per subject. Although using 2 baseline measurements is now common in inherited retinal disease (IRD) trials, some studies utilize more baseline measurements.

Simulation C – investigated the effect of drift on the different estimators. Measurements at the second visit were increased by 1 SDME on average. This phenomenon is possible with learning occurring between the two baseline measurements such as in different forms of perimetry(5) or fatigue occurring between measurements (a decrease of 1 SDME would give equivalent results).

Simulation D – investigated the performance of the estimators when the distribution of the measurement errors is not normal. For example, right skewness may be unavoidable in certain tests that have a minimum value but no upper limit. This “flooring effect” is common in microperimetry (6,7). Heavy tails from outliers may be the result of measurement contamination by an inexperienced evaluator or sub-optimal testing conditions.

Simulation E – investigated the performance of the jackknife and bootstrap (see appendix). These methods use resampling approaches to quantify the bias and variance of an estimator, which then can be used to create confidence intervals rather than just a point estimate of the TRV.

RESULTS

Estimator performance as a function of sample size

As expected, every estimator performed better (less bias, smaller variance) when more data were available (Figure 1, Table 1). Above a sample size of 50, all estimators performed similarly well. Bias is near 0 for all estimators; the standard errors are comparable and small relative to the parameter being measured (σ = 1). Below a sample size of 10, the unbiased change score estimator was the only unbiased estimator. The standard errors ranged from moderate for the mixed effects model to large for the unbiased estimator.

Figure 1:

The (A) bias and (B) standard error of 5 estimators of TRV as a function of sample size from 4 to 75 subjects. The 5 TRV estimators are the mixed effects model fit by maximum likelihood estimation, the mixed effects model fit by restricted maximum likelihood estimation, the pooled estimator, the fixed effect estimator (Bland-Altman), and the unbiased fixed effect estimator. The data for this figure used 2 baseline measurements, no drift, large patient heterogeneity (), and normal error distribution with true standard deviation σ = 1.

Table 1.

Bias and standard deviation for two estimators of Standard Deviation of Measurement Error (SDME): Fixed Effect (FE) estimator and Unbiased Fixed Effect (UBFE) estimator. FE estimator is equivalent to Bland-Altman approach when there are two measurements. UBFE estimator uses an alternative denominator to remove bias of FE estimate. Table entries are given as a proportion of the true measurement error. For example, for 2 measurements on each of 10 subjects, the FE estimator is 2.7% too low on average and deviated by 23% of the true value.

| 2 measurements | 3 measurements | 4 measurements | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE | UBFE | FE | UBFE | FE | UBFE | |||||||

| n | bias | sd | bias | sd | bias | sd | bias | sd | bias | sd | bias | sd |

| 2 | −0.202 | 0.603 | 0 | 0.756 | −0.114 | 0.463 | 0 | 0.523 | −0.079 | 0.389 | 0 | 0.422 |

| 3 | −0.114 | 0.463 | 0 | 0.523 | −0.060 | 0.341 | 0 | 0.363 | −0.041 | 0.282 | 0 | 0.294 |

| 4 | −0.079 | 0.389 | 0 | 0.422 | −0.041 | 0.282 | 0 | 0.294 | −0.027 | 0.232 | 0 | 0.239 |

| 5 | −0.060 | 0.341 | 0 | 0.363 | −0.031 | 0.246 | 0 | 0.254 | −0.021 | 0.202 | 0 | 0.206 |

| 6 | −0.048 | 0.308 | 0 | 0.323 | −0.025 | 0.221 | 0 | 0.226 | −0.017 | 0.181 | 0 | 0.184 |

| 7 | −0.041 | 0.282 | 0 | 0.294 | −0.021 | 0.202 | 0 | 0.206 | −0.014 | 0.165 | 0 | 0.168 |

| 8 | −0.035 | 0.262 | 0 | 0.272 | −0.018 | 0.187 | 0 | 0.191 | −0.012 | 0.153 | 0 | 0.155 |

| 9 | −0.031 | 0.246 | 0 | 0.254 | −0.015 | 0.175 | 0 | 0.178 | −0.010 | 0.144 | 0 | 0.145 |

| 10 | −0.027 | 0.232 | 0 | 0.239 | −0.014 | 0.165 | 0 | 0.168 | −0.009 | 0.135 | 0 | 0.137 |

| 11 | −0.025 | 0.221 | 0 | 0.226 | −0.012 | 0.157 | 0 | 0.159 | −0.008 | 0.129 | 0 | 0.130 |

| 12 | −0.022 | 0.211 | 0 | 0.215 | −0.011 | 0.150 | 0 | 0.152 | −0.008 | 0.123 | 0 | 0.124 |

| 13 | −0.021 | 0.202 | 0 | 0.206 | −0.010 | 0.144 | 0 | 0.145 | −0.007 | 0.117 | 0 | 0.118 |

| 14 | −0.019 | 0.194 | 0 | 0.198 | −0.010 | 0.138 | 0 | 0.139 | −0.006 | 0.113 | 0 | 0.114 |

| 15 | −0.018 | 0.187 | 0 | 0.191 | −0.009 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.134 | −0.006 | 0.109 | 0 | 0.109 |

| 20 | −0.013 | 0.161 | 0 | 0.163 | −0.007 | 0.114 | 0 | 0.115 | −0.004 | 0.093 | 0 | 0.094 |

| 25 | −0.010 | 0.144 | 0 | 0.145 | −0.005 | 0.102 | 0 | 0.102 | −0.003 | 0.083 | 0 | 0.083 |

| 30 | −0.009 | 0.131 | 0 | 0.132 | −0.004 | 0.093 | 0 | 0.093 | −0.003 | 0.076 | 0 | 0.076 |

| 35 | −0.007 | 0.121 | 0 | 0.122 | −0.004 | 0.086 | 0 | 0.086 | −0.002 | 0.070 | 0 | 0.070 |

| 40 | −0.006 | 0.113 | 0 | 0.114 | −0.003 | 0.080 | 0 | 0.080 | −0.002 | 0.065 | 0 | 0.065 |

| 50 | −0.005 | 0.101 | 0 | 0.101 | −0.003 | 0.071 | 0 | 0.072 | −0.002 | 0.058 | 0 | 0.058 |

Abbreviations: sd - standard deviation, FE - Fixed Effect, UBFE - Unbiased Fixed Effect.

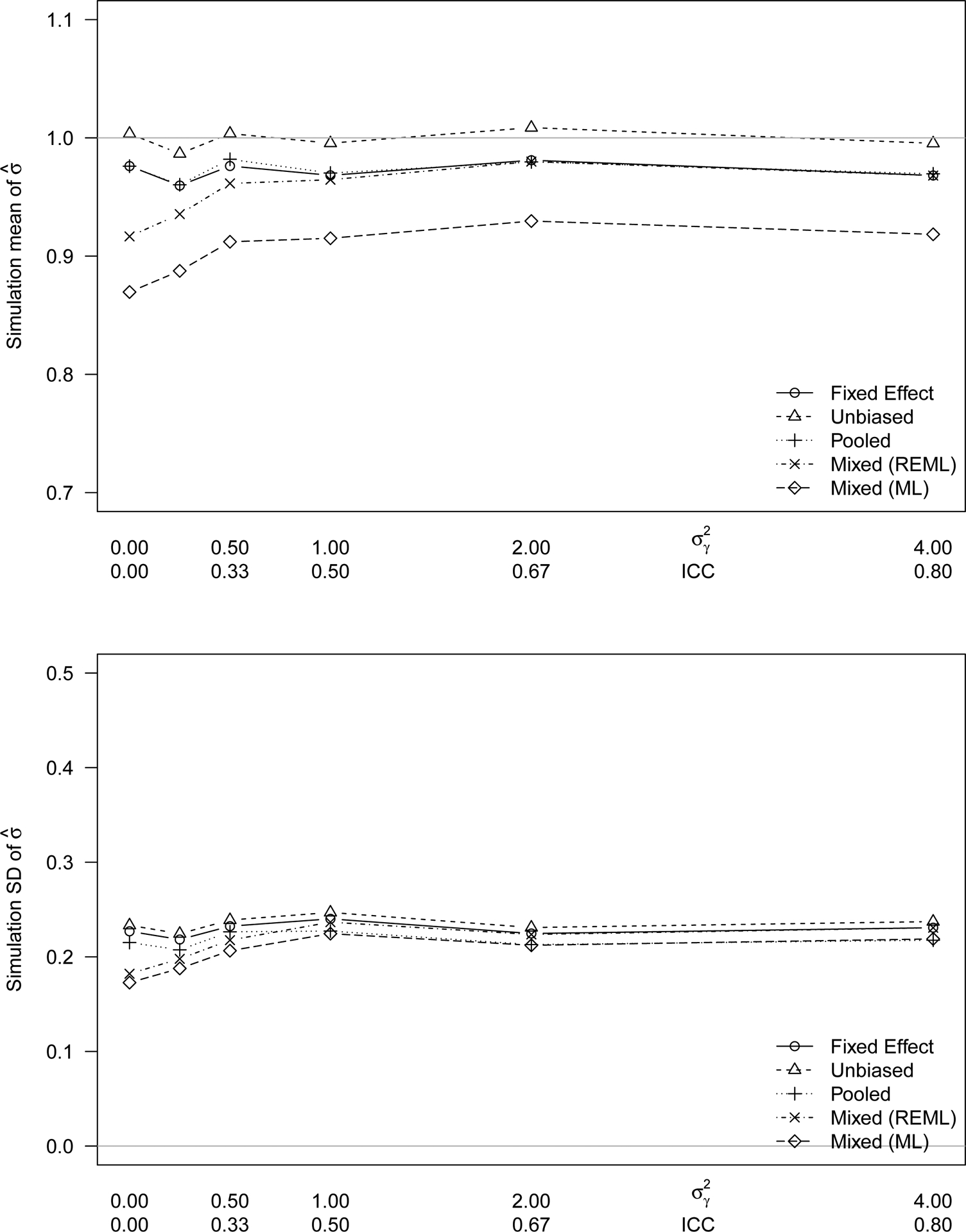

Simulation A - Estimator performance as a function of patient heterogeneity

The amount of patient heterogeneity does not affect the performance (bias and standard error) of the fixed effect model and the pooled estimator (Figure 2). The mixed effects model estimator is more negatively biased for situations where there is little or no subject heterogeneity. The measurement error and the patient variability are conflated in the model fit.

Figure 2:

The (A) bias and (B) standard error of 5 estimators of TRV as a function of subject heterogeneity from ICC=0 to ICC=0.8. The 5 TRV estimators are the mixed effects model fit by maximum likelihood estimation, the mixed effects model fit by restricted maximum likelihood estimation, the pooled estimator, the fixed effect estimator, and the unbiased fixed effect estimator. The data for this figure used 2 baseline measurements, no drift, 10 subjects, and normal error distribution with true standard deviation σ = 1.

Simulation B - Estimator performance as a function of number of baseline measurements

Additional observations at baseline improve the estimates of TRV for estimators that can use them. For example, the standard error of the fixed effect estimator decreases from 0.23 to 0.16 when a third measurement is available (Figure 3, Table 1). There is further improvement with a fourth measurement but the improvement diminishes with each additional measurement.

Figure 3:

The (A) bias and (B) standard error of 4 estimators of TRV as a function of the number of observations on each subject at baseline from 2 to 4. The 4 TRV estimators are the change score estimator that uses only the first two measurements, the fixed effect model using all available measurements, and their unbiased analogs. The data for this figure used large patient heterogeneity (), no drift, 10 subjects, and normal error distribution with true standard deviation σ = 1.

Simulation C - Estimator performance as a function of drift

The pooled estimator implicitly assumes that all variability in observations of the same person is due to TRV. If this is not the case, for example, if a person learns or acclimates over test iterations, that drift will cause the pooled estimator to overestimate the TRV. All other models that we considered include a term (αj) that allows drift to be measured separately from TRV.

Simulation D - Estimator performance as a function of error distribution

The skewness of the error distribution had minimal effect on the bias of the estimators. Although the bias correction used to create the unbiased estimator was derived from the normal distribution, it still appears nearly unbiased. The bias of remaining estimators likewise changed very little. The standard error of each estimator increases a few percentage points between the symmetric normal distribution and the skewed half-normal distribution (see Supplemental Figure 1).

Simulation E - Jackknife and Bootstrap Estimates of Estimator Variability

The bootstrap estimate of the standard error underestimated the true variability of all the estimators we considered, particularly for small samples. The jackknife method was more accurate than the bootstrap method for all sample sizes (Figure 4). The negative bias of both methods was slightly worse with non-normally distributed errors (not shown).

Figure 4:

The bias of the jackknife and bootstrap estimates of the estimator variability for the fixed effect and unbiased estimators as a function of sample size. The thick lines are the true standard deviations of the estimators. The dashed and dotted lines are the average standard deviations estimated by jackknife and bootstrap, respectively. The data for this figure used large patient heterogeneity (), 2 baseline measurements, no drift, and normal error distribution with true standard deviation σ = 1.

DISCUSSION

Our study addresses the unmet need within ophthalmology clinical trials for assessing TRV by testing the performance of different TRV calculation methods. We simulated relevant study parameters to determine the most appropriate method for unique scenarios that arise in IRD phase I/IIa gene therapy clinical trials. The results of our simulations show that the TRV calculation method impacts the estimated variance depending on simulation parameters, suggesting that each clinical trial warrants a specific TRV calculation method based on characteristics such as; 1) sample size, 2) outcome measures susceptible to drift (learned effect or fatigue), and duration of the trial susceptible to drift from natural disease progression, 3) number of baseline measurements per subject, 4) heterogeneity of the study population, and 5) observer errors made in measuring leading to skewness.

In investigating the effect of the heterogeneity of the subjects on variance estimation (Simulation A), we observed that the REML mixed effects model estimator underestimates the SDME when the subjects are homogenous relative to the measurement error (i.e., small ICC). Conversely, the UB Change Score method offers a more accurate measure of SDME with a homogenous subject pool, and therefore should be used with a small ICC. If there are more than 2 baseline measurements, the fixed effect model, which uses all measurements, has less bias and smaller standard deviation than the change score, which uses only 2 measurements per person, and therefore should be used in trials that accrue more than 2 baseline measurements (Simulation B).

However, all estimators have high variance with a small sample size (n < 10), likely to be 30–40% different than the true SDME (Simulation A). The UBCS is most accurate in estimating SDME, but tends to have the highest variability, while the other estimators introduce some bias for lower variability. At a sample size greater than ten, the differences between the methods are minimal and all three methods can be used. We recommend using the change score estimator method for clinical trials with sample sizes below 10.

In investigating the effect of drift on the different estimators, we observed that the pooled estimator model does not capture drift, instead incorporating this drift into the estimate of the SDME term and thereby over estimating SDME. Thus, the pooled estimator should not be used when there is a systematic change between the first and second visits for all individuals. In a phase I/IIa trial of gene therapy for X-linked retinoschisis, Cukras et al. observed drift between baseline 1 and baseline 2 measurements that was attributed to a systematic shift of machine reference(8). The authors decided to only use baseline 2 reading, ignoring baseline 1. In this case, a fixed effect regression model or a mixed effects model would have accounted for drift while maintaining an accurate measure of variance.

The relative bias of the estimators did not change when the error distributions were non-normal (Simulation D). As seen in Simulation A, with a normal distribution of error, the unbiased change score estimator is closest on average to the truth. The others have negative bias. However, regardless of the error distribution pattern, other test parameters hold more relevance in selecting an estimator method.

The jackknife and bootstrap standard errors are often used to estimate the accuracy of the SDME estimators in a single sample. We found that for sample sizes greater than 50, all methods of calculating SDME perform similarly with jackknifing and bootstrapping (Simulation E). With small sample sizes, the bootstrap estimates of SDME error term were severe underestimates of the true SDME. The jackknife estimates are mildly low but much better than the bootstrap estimates. The jackknife is more accurate for the change score method than for the pooled estimator.

The ideal phase I/IIa study has at least 20 subjects and uses the unbiased change score estimator or its fixed effect model generalization if there are more than two baseline measurements.

However, phase I/IIa clinical trials are usually constrained by low number of participants, and these study parameters are often not possible. Nevertheless, the study investigators should at least have a quantitative estimate of the error present in their data analysis when determining if there has been a true change from baseline due to intervention. We recommend researchers reference Table 1 for this purpose.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: The bias of 4 estimators of TRV as a function of the amount of drift between two baseline measurements The 4 TRV estimators are the fixed effect model, the unbiased estimator, the pooled estimator, and the mixed effects model. The data for this figure used large patient heterogeneity (), 2 baseline measurements, 10 subjects, and normal error distribution with true standard deviation σ = 1.

Supplemental Figure 2: The (A) bias and (B) standard error of 4 estimators of TRV as a function of the skewness of the measurement error distribution from 0 (symmetric, normal) to 0.99 (half-normal). The 4 TRV estimators are the fixed effect, the unbiased, pooled, and the mixed effect. The data for this figure used large patient heterogeneity (), no drift, 10 subjects, 2 observations per subject and true standard deviation σ = 1.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health grants K23EY026985

APPENDIX: TEST-RETEST VARIABILITY METHODS

The fixed effects and mixed effects models are based on the equation

where i = 1..n indexes the patients, j = 1..ni indexes the observations within each patient, and the errors, ϵij, are independent. The error term has mean 0 and standard deviation σ, which is the SDME, the TRV parameter of interest. The fixed effects models estimate the person effects, μi, as fixed unknown parameters. The typical estimate of σ is the square root of the mean squared error (MSE):

where the are the fitted values and v is the error degrees of freedom. If there are exactly two measurements per patient (i.e., ni = 2), then v = n − 1 and the estimate is the same as from the Bland-Altman method (i.e., the standard deviation of the n differences, divided by ). This equation provides the typical unbiased estimator of the variance: . If the errors, ϵij, are normally distributed, then an unbiased estimator of the standard deviation is obtained by using a different denominator, the mean of the χv distribution, which is , or approximately, .

The mixed effects models assume the person effects, μi, are independent random draws from a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation σμ. Common estimation methods of mixed effects model parameters are by maximum likelihood (ML) and by restricted maximum likelihood (REML). As ML underestimates variance parameters, particularly in small samples, we only consider REML.

The pooled estimator is derived from a two-step process. First, for each person i, the sample variance of his ni measurements is computed:

Second, a weighted average of these n variance estimates is taken. The resulting pooled estimate of the SDME is

APPENDIX: BIAS AND VARIABILITY OF ESTIMATORS

The quality of an estimator can be measured in several ways; we focus on the bias and the variance. If is an estimator of σ, then its bias is , where E is the expected value operator. If , the estimator is called unbiased. The variance of an estimator is , that is, the expected squared distance from the mean, and smaller is better.

For certain data models, the bias and variance of some estimators can be explicitly computed. However, the jackknife procedure is a data-driven approach that evaluates an estimator’s bias and variance. Briefly, the estimator is computed n times, leaving each person out of the calculation once. From these n estimates, denoted , come estimates of the bias,

and the variance,

Another data-driven approach to bias and variance estimation is the bootstrap. The estimator is calculated on B resamples, each of size n drawn with replacement from the original sample. From these B estimates, denoted , come estimates of the bias,

and the variance,

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

This research has not been previously published or presented.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bittner AK, Mistry A, Nehmad L, Khan R, Dagnelie G. Improvements in Test–Retest Variability of Static Automated Perimetry by Censoring Results With Low Sensitivity in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020. November 20;9(12):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bland JM, Altman D. STATISTICAL METHODS FOR ASSESSING AGREEMENT BETWEEN TWO METHODS OF CLINICAL MEASUREMENT. The Lancet. 1986. February 8;327(8476):307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeffrey BG, Cukras CA, Vitale S, Turriff A, Bowles K, Sieving PA. Test–Retest Intervisit Variability of Functional and Structural Parameters in X-Linked Retinoschisis. Transl Vis Sci Technol [Internet]. 2014. October 3 [cited 2019 Oct 9];3(5). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4187428/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical Methods For Assessing Measurement Error (Reliability) in Variables Relevant to Sports Medicine: Sports Med. 1998;26(4):217–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dedania VS, Liu JY, Schlegel D, Andrews CA, Branham K, Khan NW, et al. Reliability of kinetic visual field testing in children with mutation-proven retinal dystrophies: Implications for therapeutic clinical trials. Ophthalmic Genet. 2018. January 2;39(1):22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H, Bittencourt MG, Wang J, Sophie R, Annam R, Ibrahim MA, et al. Assessment of Central Retinal Sensitivity Employing Two Types of Microperimetry Devices. Transl Vis Sci Technol [Internet]. 2014. September 12 [cited 2020 May 19];3(5). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4164074/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg JS, Saßmannshausen M, Pfau M, Fleckenstein M, Finger RP, Holz FG, et al. Evaluation of Two Systems for Fundus-Controlled Scotopic and Mesopic Perimetry in Eye with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Transl Vis Sci Technol [Internet]. 2017. July 13 [cited 2020 Jul 19];6(4). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509379/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cukras C, Wiley HE, Jeffrey BG, Sen HN, Turriff A, Zeng Y, et al. Retinal AAV8-RS1 Gene Therapy for X-Linked Retinoschisis: Initial Findings from a Phase I/IIa Trial by Intravitreal Delivery. Mol Ther. 2018. September 5;26(9):2282–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: The bias of 4 estimators of TRV as a function of the amount of drift between two baseline measurements The 4 TRV estimators are the fixed effect model, the unbiased estimator, the pooled estimator, and the mixed effects model. The data for this figure used large patient heterogeneity (), 2 baseline measurements, 10 subjects, and normal error distribution with true standard deviation σ = 1.

Supplemental Figure 2: The (A) bias and (B) standard error of 4 estimators of TRV as a function of the skewness of the measurement error distribution from 0 (symmetric, normal) to 0.99 (half-normal). The 4 TRV estimators are the fixed effect, the unbiased, pooled, and the mixed effect. The data for this figure used large patient heterogeneity (), no drift, 10 subjects, 2 observations per subject and true standard deviation σ = 1.