Abstract

Formerly incarcerated, homeless women on parole or probation experience individual-and structural-level barriers and facilitators as they prepare to transition into the community during reentry. A qualitative study was undertaken using focus group methods with formerly incarcerated, currently homeless women (N=18, Mage= 37.67, SD 10.68, 23–53 years of age) exiting jail or prison. Major themes which emerged included the following: 1) access to resources - barriers and facilitators during community transition, 2) familial reconciliation and parenting during community transition, and 3) trauma and self-care support during community transition. These findings suggest a need to develop multi-level interventions at the individual, program and institutional/societal level with a gender-sensitive lens for women who are transitioning to community reentry. It is hoped that providing such resources will reduce the likelihood of homelessness and reincarceration.

Keywords: substance use, trauma, homelessness, incarceration

Introduction

The United States (U.S.) is home to the largest incarcerated population globally; currently, women are one of the most rapidly growing subgroups behind bars (Allen et al., 2010; Fuentes, 2014; Golder et al., 2014). In the criminal justice system, there are nearly 1.3 million women (The Sentencing Project, 2015). Over a ten year span (1999–2009), there was a 25% increase in the number of women incarcerated (Garcia & Ritter, 2012). The percentage of U.S. women on probation has increased from 23% in 2005 to 25% in 2015 (out of a total of 3,789,800 adults on probation) (Kaeble & Bonzcar, 2017). Across the U.S., there are approximately 101,000 women in local jails and 99,000 in State Prisons (Kajstura, 2019); annually, 81,000 women are released from state prisons (Sawyer, 2019). The following sections will discuss the gendered pathways to incarceration and addiction, factors influencing community reentry, physical and mental health needs, and employment and housing challenges with a particular focus on women experiencing homelessness during reentry with substance use issues.

Gendered Pathways to Incarceration and Addiction across the Life Course

Gendered pathways to incarceration recognize biological, psychological, and social realities that encompass the unique pathways and life events of the female experience of incarceration (Salisbury & Voorhis, 2009). Gaining a sound perspective related on gendered pathways to incarceration requires an understanding of individual-level characteristics across the life course (Huebner et al., 2010; Mallicoat, 2011; 2014) which may include poverty, poor education, irregular employment histories (Bloom et al., 2003), self-medicating behaviors (e.g., substance use) (Mumola & Karberg, 2007; Salisbury and Voorhis, 2009) and trauma (Salisbury and Voorhis, 2009). Pathways to addiction for women are also important to note as often they intersect with the criminal justice system (Bloom et al., 2004) and may begin in early years due to drug use exposure at home and being in an environment that is accepting of substance use (Mallicoat, 2014).

Compared to women without early life history of abuse, women who have experienced abuse are at greater risk for substance use (Mallicoat, 2014). In a qualitative paper based on the current study, we found three major categories involved in women’s discussions surrounding substance use and risk for recidivism which included factors involved in relapse, and factors influencing desire to remain drug free (Nyamathi et al., 2016). Further, illicit drugs often serve as maladaptive coping mechanisms, leading to women’s criminal justice involvement (Scroggins & Malley, 2010).

Factors Influencing Community Reentry

The process of returning to the community after having exited jail or prison is known as ‘reentry’ which can be a liminal, transitional state (Mears & Cochran, 2015). Although large numbers of women are on parole or probation, most programs for women have been modeled for men (Garcia & Ritter, 2012). As a result, reentry needs for women include healthcare, counseling, housing, education, and transportation (Scroggins & Malley, 2010). Clearly, a gendered approach to community transition is a critical area to explore during reentry; specifically, it is important to provide childcare and parenting services because if these needs go unmet, then transitioning during reentry becomes more difficult (Scroggins & Malley, 2010).

During reentry, reconnecting with family is critical; however, family discord may be present including family violence (Bobbitt et al., 2006; Stansfield et al., 2020). Familial incarceration impacts health of family members increasing perceived stress and cardiovascular risk (Connors et al., 2020). Healthcare, counseling and substance abuse services, along with adequate and affordable housing are also critical tangible resources which are needed to support a successful transition (Scroggins & Malley, 2010). Further, skill training and social support is essential during this time to circumvent reincarceration (Scroggins & Malley, 2010).

Physical and Mental Health Needs of Women Exiting Correctional Institutions

Former inmates with a history of incarceration are often faced with multiple chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, depression and anxiety (Binswanger et al., 2012; Colbert et al., 2013; Grella & Greenwell, 2007), along with deficits in knowledge related to managing those chronic conditions (Salem et al., 2013) and may experience intersectional stigma (Turan et al., 2019). Close to two-thirds (64.7%) of women sampled during reentry had a history of mental illness, and the majority (88.2%) had a history of addiction to drugs or alcohol (Colbert et al., 2013). Among women with a recent history of incarceration, specific mental health conditions included depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, physical health issues such as back and knee problems (Colbert et al., 2013). Intersectional stigma is the convergence of multiple stigmatized identities and can be additive impacting behaviors, mental, and physical health (Turan et al., 2019).

Fragmented care and lack of access to care influence reentry. However, while a high proportion of criminally-justice involved individuals are eligible for Medicaid (Albertson, Scannell, Ashtari, Barnett, 2020), they may lose health insurance coverage when they enter the criminal justice system (Gates, Artiga, Rudowitz, 2014) which may persist during reentry (Albertson, Scannell, Ashtari, Barnett, 2020). The Affordable Care Act expands health coverage for those during reentry; in fact, during the first 60 days of reentry, individuals can enroll in Marketplace coverage (Gates, Artiga, Rudowitz, 2014).

Employment Challenges During Reentry

Women on parole and probation also experience challenges with limited employment; thus, affordable housing may be lacking (Grella & Greenwell, 2007; Hall et al., 2001; Salem et al., 2013) precipitating homelessness and possible interaction with the criminal justice system. During reentry, opportunities to find employment for those with a history of incarceration is also negatively impacted (Staton et al., 2019) because when applying for jobs, those with a history of incarceration must report their felony conviction to employers who may be unwilling to hire a formerly incarcerated individual. As a result, those on parole and probation experience difficulties finding gainful employment (Mears & Cochran, 2015).

Housing Challenges During Reentry

Among those with a history of incarceration, housing-related challenges precipitate homelessness (To et al., 2017). Further, individuals with a history of incarceration are competing with 46.7 million others at or near the poverty line (United States Census Bureau, 2014), making it ever more challenging to secure federally-assisted housing (Bishop, 2008). In a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study among homeless and vulnerably-housed individuals (N=1,189) in three Canadian cities, individuals who had been incarcerated within the last 12 months were less likely to be housed during the subsequent year over the two-year follow-up period (To et al., 2017). In a qualitative study among with women (N=17) whom have recently exited jail, the experience of stigma and discrimination influenced employment, housing, and reentry (van Olphen et al., 2009). Specifically, women noted that employment was more difficult to attain due to perceptions of discrimination, living wage attainment due to limited compensation and benefits (van Olphen et al., 2009). Relatedly, authors note that stigma impacts interactions and therapeutic services (van Olphen et al., 2009). All these limiting factors challenge successful reentry.

While much has been written about gendered pathways to incarceration and addiction, the purpose of this qualitative study was to understand experiences of formerly incarcerated, homeless women as they prepared to transition during community reentry. The knowledge gained will be helpful in the development of a multidisciplinary intervention program that can address their unique needs and facilitate the reentry process.

METHODS

Study Design

This study used a qualitative, cross sectional design and gathered data using three focus groups with recently incarcerated, homeless women (N=18; ages 23 to 53). Focus group methodology plays an important role in participatory action research and was selected to encourage discussion (Polit & Beck, 2019) and aid in group interaction. The focus group questions were designed to stimulate rich and detailed perspectives related to needs and perspectives among women transitioning into the community (Côté-Arsenault & Morrison-Beedy, 1999).

Setting

Participants resided in either one of two residential drug treatment (RDT) programs in Los Angeles, California. The primary site for the focus groups has staff onsite (1/15 staff to resident ratio) and individuals can reside there for six months to one year. At the time of data collection, the primary site had a total capacity of 150 men and 34 women. Both sites provided temporary housing for homeless women on parole/probation, substance abuse services, and community reentry assistance that included providing necessities, group classes, parenting classes, and employment services. The RDT staff worked closely with staff in the jails and prisons for transition planning. This study was approved by the University of California Human Subjects’ Protection Committee.

Sample

A purposive sample of 18 women was included in this study who met the following eligibility criteria: a) 18–65 years old, b) self-reported to be homeless at the time of release from jail or prison, c) currently on parole and/or probation, and d) charged with a drug-related offense. In total, 19 participants were screened and 18 were included in this study. One participant decided not to continue after screening.

Community Advisory Board (CAB)

Principles of community-based participatory methods (CBPR) were an integral part of the research process, and engaged community stakeholders and academicians in the research process (Israel et al., 1998; Jones & Wells, 2007). Prior to implementation of this study, community-based stakeholders and academic partners identified the need for the study collaboratively, the possible RDT sites, planned data collection and recruitment approach. In our previous qualitative publication with homeless, female ex-offenders (N=14), areas of need included healthcare, limitations with knowledge and challenges moving forward (Salem et al., 2013).

Once IRB approval was attained, a community advisory board (CAB) was composed of researchers with experience working with women who have had a history of homelessness and incarceration. In addition, community-based stakeholders (i.e., service providers) who had experience working with homeless female offenders and criminal justice experts from the University of California, Los Angeles and Irvine were seated at the same table. The researchers have worked with community-based organization leaders and had prolonged engagement in the field. One of the primary goals of the CAB was to modify the semi-structured interview guide (SSIG) which had been developed from our previous research, the literature, and consultations with community-based and criminal justice experts. The focus of the SSIG was to understand women’s perspectives on health and social services within and outside the RDTs. The CAB provided insight and feedback related to our findings prior and after focus groups.

Procedure

Recruitment commenced with flyers followed by informational sessions. Two researchers conducted informational sessions to provide study details to potential participants. For those interested in the study, investigators met in a private area, detailed the purpose, time, and planned procedures. Among those interested in continuing, informed consent and screening was completed. For those scheduled for focus group sessions, a meeting time in a private area of the designated facility was arranged. Interested residents who were screened as eligible were administered a short sociodemographic survey by the research staff in a private location at the facility. Each of the focus groups was audio recorded and field notes were taken during the sessions; each participant participated in one focus group session. The SSIG guided the focus group sessions which included an introduction to the purpose of the study, an icebreaker, participant introductions, and asking questions related to the needs of the women as it related to health services, resources for sobriety, abstinence, mitigating recidivism, and areas of program improvement.

Sample questions included, what are some of the reasons you think women who are coming out of jails and prisons begin drinking alcohol and use drugs again?, What do you think are the purposes which drugs and/or alcohol serve in life?, In general, what are some factors which result in women who are coming out of jails and prisons to be rearrested?

Three focus groups were conducted with four to seven participants in each focus group; each focus group lasted about one hour and fifteen minutes until data saturation was reached. The screening compensation was $3 and focus group compensation was $15.

DATA ANALYSIS

Chronological age, ethnicity/ race, country of birth, education level and length of time homeless were described using frequencies, percents, and means. Three research team members were involved in the content and thematic analysis process and utilized Microsoft Word and PowerPoint to draw maps and conceptual relationships. In the following paragraphs, trustworthiness, rigor, and thematic analysis will be described. For naturalistic inquiry to be ensured, trustworthiness of the data and rigor were safeguarded by four methods which were integrated into the data analytic process: a) confirmability, b) dependability, c) transferability, and d) credibility (Shenton, 2004).

Dependability was established by saving taped focus group recordings, guiding an independent transcriptionist to transcribe three audio files, listening and comparing audio files against transcripts, modifying text as needed for accuracy, and de-identifying the transcripts to support reliability of the findings (Shenton, 2004). An audit trail was followed which described the data analytic steps taken (Shenton, 2004) and included the development of a systematic coding grid that included the following (e.g., focus group number, pseudonym, line number for raw data, line-by-line coding, preliminary codes, categories and themes) which supported confirmability.

Researchers independently coded the transcripts and met consistently to go over the findings which supported internal validity as credibility was established by debriefing sessions (Shenton, 2004) among the researchers. First cycle coding methods generated initial line-by-line coding. Second cycle coding methods were used to recode and categorize data (Saldaña, 2013). Three research team members were involved in reviewing the codes, categories, subcategories, themes and diagrams. To support external validity or generalizability, transferability was established by describing those involved in the data analytic steps, the length of the data collection sessions and the time period of data collection (Shenton, 2004). Member checking was challenging to employ due to the transience of the homeless population; thus, the research team was involved in reviewing the findings with the community stakeholders that have extensive population-specific experience at the community-based sites.

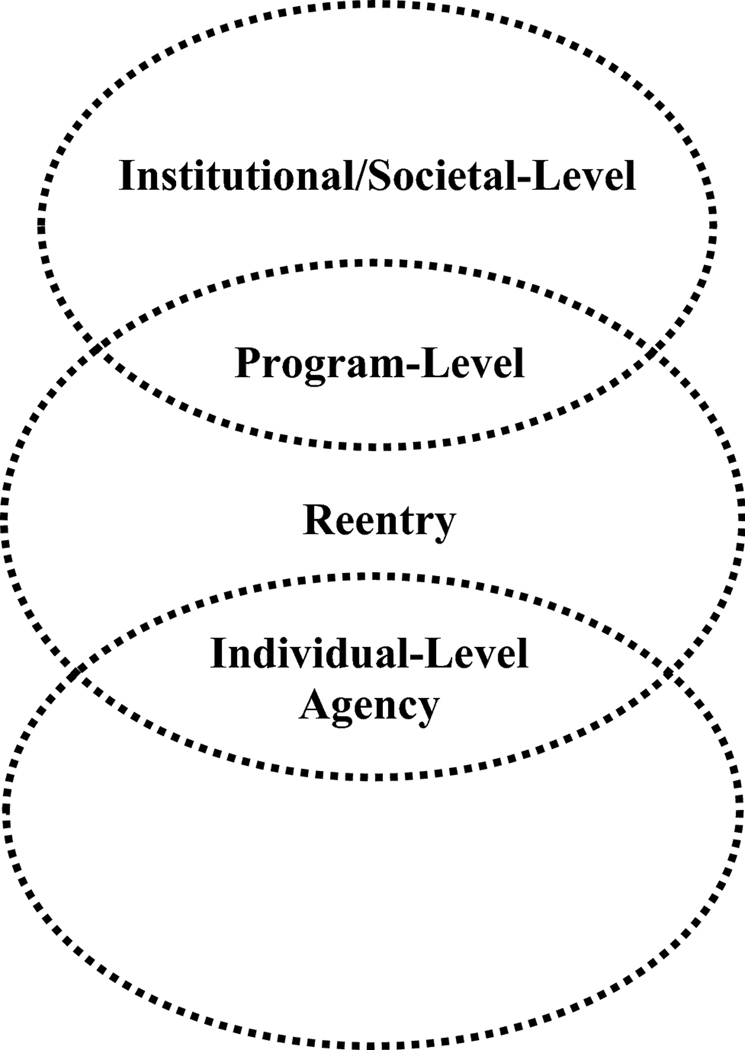

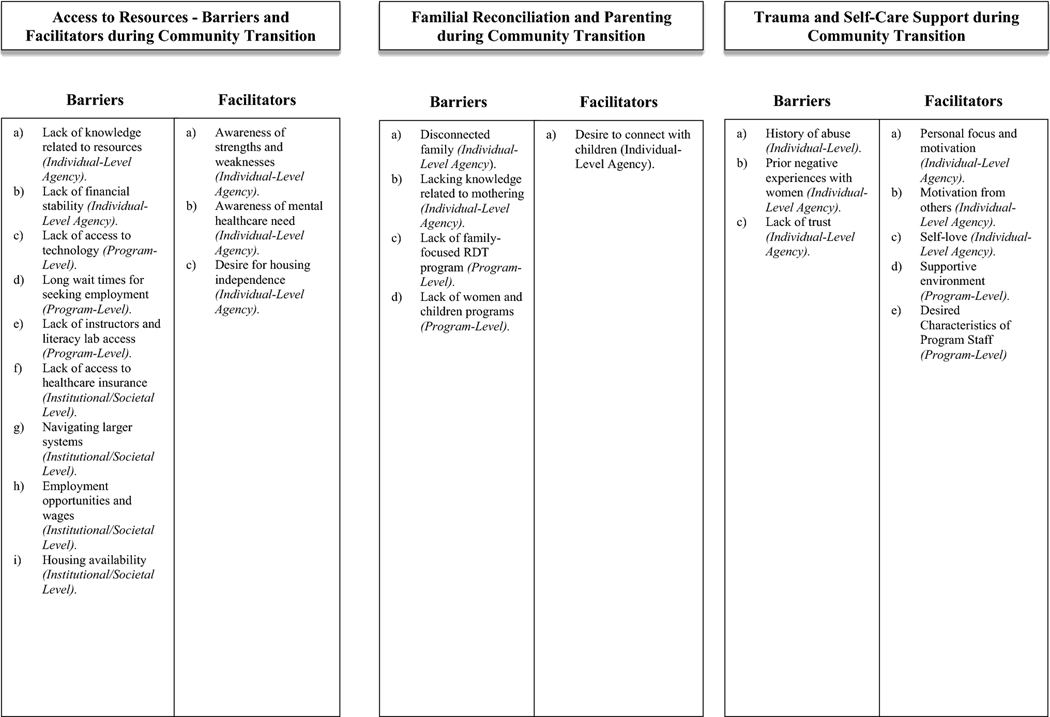

The three major themes were selected based on comparing the categories for similarities and differences, defining the categories, reassessing consistency in coding decisions and congruence between claims about the data and reality, along with grouping codes based on commonalities and differences. Figure 1 and 2 showcase major themes and subthemes.

Figure 1.

A Schematic Depicting Individual-Level Agency, Program-Level, and Institutional/Societal Level Factors as Women Transition into Community Reentry

Figure 2.

Major Themes, Barriers and Facilitators at Individual-Level Agency, Program-Level and Institutional/Societal-Level Voiced by Formerly Incarcerated, Homeless Women (N=18)

RESULTS

Table 1 reports sample characteristics of the population. The mean age of 18 participants was 38 (ages 23–53; SD 10.68) and all were female. The majority were African American/Black (50.0%), Hispanic or Latino (22.2%), or White (22.2%), self-reported having children (72.2%), and (83.3%) had a history of employment; however, currently, over half were unemployed (61.1%). Data analysis produced the following major themes were reported by the women as occurring during transitioning into community reentry: 1) access to resources - barriers and facilitators during community transition, 2) familial reconciliation and parenting during community transition, and 3) trauma and self-care support during community transition.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of Formerly Incarcerated, Homeless Women (N=18)

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Measure | Mean | SD Range |

|

|

||

| Age Range | 37.67 | 10.68 (23–53) |

|

|

||

| N | % | |

|

|

||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American/Black | 9 | 50.0 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 | 22.2 |

| White | 4 | 22.2 |

| Asian | 1 | 5.6 |

| Children | ||

| Yes | 13 | 72.2 |

| N | % | |

| Ever been employed | ||

| Yes | 15 | 83.3 |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 11 | 61.1 |

| Not working | 3 | 16.7 |

| Working full time | 1 | 5.6 |

| Working part time | 1 | 5.6 |

| Disabled | 1 | 5.6 |

| In school | 1 | 5.6 |

| Mean | SD (Range) | |

| Homeless, years | 5.58 | 5.64 (0–19) |

Themes which captured the experiences of the women during community reentry were at three differing levels; namely, barriers and facilitators due to lack of individual-level agency and those beyond the control of individual-level agency (e.g., program-level factors and societal/institutional-level factors). Barriers were demarcated as challenges which were faced at the individual-level agency which impeded community transition. On the other hand, facilitators represented aspects that made it easier to transition during community reentry. Beyond the control of individual-level agency, there were barriers and facilitators at the program-level which were confined within the perimeter of the RDT. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators at the institutional and policy-level extended beyond the program-level RDT factors as individuals prepared to enter the community.

Figure 1 depicts a Venn diagram with three concentric, overlapping circles which include perceptions of individual-level agency, program-level, and institutional/societal-level factors due to the various levels of influence on one another which existed as participants transitioned during reentry into the community. Figure 2 represents the main themes, barriers and facilitators at differing levels (i.e., individual-level, program-level and institutional/societal-level).

Theme 1: Access to Resources - Barriers and Facilitators during Community Transition

There were several barriers due to lack of individual-level agency as women prepared to transition during reentry. These included the following: a) lack of knowledge related to resources and b) lack of financial stability. First, as women prepared to transition into the community, lack of individual-level agency included lack of knowledge related to resources. Another was a perceived lack of tangible support in navigating complex reentry processes (i.e., program and systems level). One woman disclosed:

…All the information that you gather would be really nice if you had a very current and up-to-date resource book for people that got out of prison…Somewhere [we] can go and pick it up? Or, maybe it was given prior to…getting out of prison.

Another woman needed resources related to where to go to seek assistance in a crisis. During the focus groups, women questioned the changing landscape of health insurance; in particular, questions about the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and health insurance were raised. Some women had trouble understanding the difference between the ACA, Medi-Cal and details of the various plans. Others described past experiences in prison where there was a lack of adequate mental healthcare providers. In particular, one woman expressed, “Someone needs to go and talk to the officers and the staff there because the only ones that I felt like I could really confide in were psych techs and they were the only ones who helped me…”

Other barriers due to lack of individual-level agency during community transition included lack of finances. Women were clear about the specific types of positions they were interested in and described how their inability to finance schooling or vocational training hindered their ability to improve their occupational status during community reentry. One woman described:

Yeah, I mean a lot of times we don’t have the money to pay for the schooling or the advancement in our careers. But if we did, [it] might make a big difference because there’s a lot…we still can apply for…

Individual-level agency facilitators that women shared as they prepared to transition during reentry included the following: a) awareness of strengths and weaknesses (i.e., self-image, self-esteem, needs, knowledge, etc), b) awareness of mental healthcare need, and c) desire for housing independence. Women described how self-image was linked to physical appearance. One woman described her experience,

Ever since I lost my teeth, my whole personality, my whole character has changed, you know. I don’t present who I am you know. I have this totally different image going on and I hate it.

Some women shared that they would benefit from having mental health treatment; in fact, one woman noted that women need to “talk about the things that they have cluttered up inside them [and] have…a one-on-one therapist where they [can] talk. Because me, myself, I’m the type of person that needs someone like that…” She continued to share that keeping information bottled up inside did not have long term benefits. She said:

And it helped me because if a person keeps something bottled up inside of them and they feel that they have no one to talk to uh…it’s like a luggage set they’re carrying. It’s too heavy. It’s a load and they needed the relief.

Others discussed the desire to be independent and seek housing. One woman described:

I’m not sleeping on nobody’s couch because I have a big family so I didn’t want to go back …I got them [for] support but there comes a time when you want to be grown. You want to have your own…you got to be independent.

Beyond individual-level agency, perceptions of program-level barriers included a) lack of access to technology, b) long wait times for seeking employment, and c) lack of instructors and literacy lab access. Women shared that they needed access to technology during reentry, including access to a cell phone, a literacy lab, Internet and a general information line. Many of the women described access to “Obama phones” which were lifeline assistance phone plans available to those with low income. For some women, having a cell phone was critical as many were filing applications and if they did not respond within a certain amount of time, they would be cancelled. Women described that technology would facilitate job searching and that lack of ability to have cell phones were described as precipitating early exit from the RDT site. One woman emphasized:

We should be allowed to have cell phones because for those of us who…should have jobs or should be looking for them by now…you need that to fill out application. You need those cell phones.

Other women shared they didn’t know how to use a computer, were seeking general education degree (GED) resources, and some wanted to become computer technicians. One woman made apparent the challenges of being in an RDT and not being able to search for work immediately after post-incarceration. She said:

[It is a long time]… to wait before we go out and get a job. And if we have absolutely nothing to work with as far as financially…Like me, I don’t have any money coming in from anywhere.

Perceptions of program-level barriers to technology limited women to complete an educational course for further advancement. One woman detailed,

I was working on my GED before [with] the person who was running it. I don’t know what happened to him. He’s gone now…Yes. And I didn’t even get to finish my GED because they [closed] down.

The limited literacy lab hours challenged completion of a GED; in particular, some women recounted that the literacy lab on site was open for a limited amount of time. One woman described her challenges:

I was doing the pretest and they was trying to see where [I needed help] And … he was going to give me the books to study and then try again. And that’s what we was working on but then they closed down the lab.

Beyond the program-level RDT factors, several institutional/societal level factors included a) lack of access to healthcare and insurance, b) navigating larger systems, c) employment opportunities and wages, and d) housing availability prior to community reentry. In terms of healthcare, not only were dental needs described, but, lack of access to healthcare and insurance affected dental care during community reentry. One woman described:

I had a hole in my tooth and that’s when I went in…and they were unable to take care of it due to my medical situation. I didn’t have Medi-Cal or anything.

Another woman shared the challenges she faced navigating larger systems. She described,

I have five kids. I need to have contact….I have children, children’s court for the rest of them you know. I have a lot of things going on with my self… not going to be able to keep up with all my stuff …

Other women shared their concern about employment opportunities with pay greater than the minimum wage. One woman shared,

We don’t want to be out there working minimum wage because [we used to make] fast money and stuff you know, and getting everything we want while we’re out there…Doing whatever we have to do to get that money.

Other barriers included lack of access to employment and vocational training due to criminal justice system involvement. Similarly, women described a desire for financial stability. One woman described:

…What led me back to incarceration would be finances, not being able to get- find stability because … I want to be comfortable with my finances. And it’s either hard finding employment or its hard being trusted or you know, given a job opportunity because of our backgrounds or you know some of the discrimination in society.

Another barrier beyond the control of program-level factors was perceived stigma of incarceration which negatively impacted securing housing and was another perceived institutional/societal level challenge women experienced as they prepared to transition during reentry. One woman said:

It is to remove the box off a housing application and job employment applications that says have you ever been convicted of a crime because we’re learning to be honest today in our lives. And so when we [say] … I’ve been a criminal before, no matter how skilled we are, we are turned down for this housing and for this employment.

Theme 2: Familial Reconciliation and Parenting during Community Transition

Several barriers due to individual-level agency during reentry included a) disconnected family and b) lacking knowledge related to mothering. Women described the effects of incarceration on their families and reunification needs post-incarceration. Some women describe the desire to find their children; however, for some, once found, sometimes their children preferred not to keep in touch with them. One woman expressed that communicating by phone is not the same given that she has been out of her daughter’s life since she was five years old and she wanted to have transportation to unite. Another woman shared:

I lost my children a long time ago. I know they’re grown and I tried to go on Facebook. I found one of them but he won’t talk to me. The other two, one’s in a mental health hospital, the 16-year-old. And I don’t know where the 23-year-old is. So I do need help to find them.

Whereas, individual-level agency barriers to parenting included lacking knowledge related to mothering.

…People don’t know how to be parents. They didn’t have good parents themselves. So it’s like the people that are mentoring to us, they have to be practicing what they’re preaching. They have to be good role models for us to really look at them and try to follow suit and you know walk in their light too.

While another woman expressed the following:

…I feel it’s so important for a mother getting out of prison and a child …to have a class or therapy to go to build that bond back so … [as to] why they shouldn’t go down the road your mother been down….

Individual-level agency facilitators that women shared would help them transition into the community included the desire to reconnect with their children. Specifically, one woman recounted, “…Your mother instinct kick in, you want your kids…”

Beyond the control of individual-level agency, perceptions of program-level barriers related to the family as women prepared to transition during reentry. These included: a) lack of family-focused RDT program and b) lack of women and children programs. Limited facilities which allow mothers and children to live together hinder many women to reunite with family, as many wanted their children to live at the facilities with them. Another woman shared that the RDT facilities should provide support for a family meal and family day. Further, women described that they felt that women leave RDT programs prematurely because their families are seeking their support and they are unable to provide that support. To illustrate, one woman said:

…I also would like to bring up that they [the program] should be considerate to immediate or important family issues because you have a lot of people that run away or just leave the program…

Perceptions of program-level barriers related to the family as women prepared to transition during reentry included not having access to a program that would accept children along with mothers. One woman expressed:

And I feel like there should be more programs for women with children … To get out and get their children back and get on the right track. And there [are] not a lot of programs at all as far as that goes.

Theme 3: Trauma and Self-Care Support during Community Transition

Several individual-level agency barriers experienced by women as they prepared to transition included: a) history of abuse, b) prior negative experiences with women, and c) lack of trust. Prior experiences with others influenced current behaviors; in particular, some women noted that past relationships included a history of abuse. One woman expressed, “I can control what I’m going to do for money to get high, you know, because I have control over that. I didn’t have control of being abused you know, being taken advantage of.” Another woman detailed, “Yeah so core issues, sexual abuse, abandonment, rape, uh, yeah, women get beat, child molest, all kinds of stuff.”

Prior negative experiences with women also made it challenging to receive current support from women. It is less clear if these were romantic versus non-romantic relationships. However, learning how to build those relationships based on previous experiences with other women was mentioned. One woman described:

It’s very hard for me to trust women in general due to my past and stuff but I’m learning how to deal with that while here in this program. And that’s the thing, I’m learning how to build relationships more with women than going to find a relationship with a man…

Other women shared some of their prior relationships with other women and lack of trust was discussed as women prepared to transition during reentry. A number of individual-level agency facilitators for self-care were discussed and included the following: a) personal focus and motivation, b) motivation from others, and c) self-love. One woman illustrated the importance of personal focus and motivation. She said:

…Staying focused is really important you know. Staying focused and knowing, you know, what your journey is…help is out there…it exists. You just have to be willing and you know motivated. You have to motivate yourself. You can’t wait for people to motivate you, you know.

While on the other hand, one woman described that motivation from others would be helpful. She shared,

Sometime a person do need… that motivation. If you’ve never been motivated or you don’t have no tools, you can’t motivate yourself.

While women discussed comradery between one another, others described that they felt that each individual goes through a different process and often self-love needs to begin within. One woman expressed:

Yes, because at the end of the day you know, it’s me, myself and I, you know. I have my sisters and stuff, you know, and I have the administrators, but it’s a process. I mean we all go through our process differently…and I can only understand my process to myself. Others can only try to relate to my process…We all have a story and we all process differently….And I need to love myself before I let anybody else love me or before I love anybody else because I can love for the wrong reasons or I could be loved for beneficial reasons.

Several support-related, program-level facilitators were discussed as women prepared to transition during reentry included: a) supportive environment, and b) desired characteristics of program staff. One woman recounted,

And we cut ourselves open and empty our cups in our group about things we will take to our grave. So we are content with the presence and the safety of our sanctuary that we share with each other, those deep dark secrets.

Other ways in which women supported one another was during the day. One woman described,

We praise each other. We have a group called in morning gathering. And we give gratefulness and affirmations right…Those are things that we do with each other spiritually to build each other you know.

Existing support systems were voiced by other women; in particular, women shared that they felt that others did not give up on them and that communication between one another existed. Women described that they did communicate with one another in various locations at the RDT sites and provided a sense of support during difficult times. One woman described,

And the best thing that I like about it is they don’t give up on you because I know I can be very unapproachable at times you know. I could just mute everything out. Nobody exists. But you know, they’ll approach me and I ignore it. I give it about 10, 15 minutes and another one is right behind…

Another program-level facilitator was the supportive environment. One woman said,

…The demonstrators that are here, it’s what helps me because I think my biggest problem or issue that I have about coming here was accepting love or that somebody truly does care you know.

Further, other women shared that it would be helpful for the future program staff to have specific personal characteristics such as compassion, an open mind, heart and fewer staff turnover. Other women described program-level facilitators which would be desired as women prepared to transition during reentry included that they felt they would like to work with other women who have had similar experiences. For instance, one woman shared,

…If you are a person who has overcome your addiction, you know, or you’re still doing your process, I’m going to relate to you, you know.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand experiences of formerly incarcerated, homeless women as they prepared to transition during community reentry. They described their perceptions of barriers and facilitators at the individual-level, program-level and institutional/societal level. For some women, strong feelings were shared related to their lack of knowledge about resources. Likewise, women described seeking access to dental and mental healthcare, along with questions related to health insurance. Individual-level agency facilitators which were described included a personal awareness of the importance for healthcare; however, individual-level agency barriers included previous prison experiences with a lack of mental health counselors.

While previous research has demonstrated that limited access to care, long wait times and lack of access to medication are common areas of need among women during reentry (Salem et al., 2013), less is known regarding individual and system-level factors which are operating concurrently and influencing the transition during community reentry. Understanding barriers and facilitators at varying individual, program and institutional levels will enable those working with this community to tackle each level with a higher degree of success during reentry.

Formerly incarcerated persons have increased chronic health conditions (Fox et al., 2014) and lack of health insurance (Fu et al., 2013) - all of which have predicted recidivism. Women described lack of knowledge related to the difference between the ACA and Medi-Cal; further, they questioned each plan. Given the changing landscape of healthcare reform, knowledge related to health insurance is a significant area of need and the critical importance of connecting individuals into care prior to release and during reentry was evident. Therefore, it is important to educate women about healthcare insurance and options at discharge from jail or prison.

Our findings similarly revealed that for many formerly incarcerated women, there was a strong desire to seek housing and be independent; however, limited housing options were available. Given the varied responses by the women in seeking housing options, it’s important to consider that individual-level agency, motivation and desire, along with goal setting is critical. It would be ideal for housing planning to occur prior to release from jail or prison to address individual-level barriers, encourage facilitation and promote sustainability. Previous research has documented programs that providing health and social services during reentry has positive outcomes (Richie et al., 2001).

Critical time intervention has been previously applied to homeless persons with a history of severe mental illness (Herman et al., 2011) and is one solution-oriented approach which could be applied to this population during a number of critical transition points during the trajectory of jail, reentry, and home (Draine & Herman, 2007; Herman et al., 2011). Preparation for release would begin while incarcerated and include transition from jail and/or prison to an RDT facility. During this time, there would be a strengthening of relationships between family and friends, along with building problem solving skills and motivational coaching (Draine & Herman, 2007). Viable implementation of this intervention would require the multidisciplinary involvement of the local county Sheriff’s Department, community-partnered residential drug treatment facilities, housing and urban development and single room occupancy providers. While this is one reasonable, solution-oriented approach, this is not a complete balm to this complex issue, which would require local criminal justice, housing and RDT partnership.

Women described the challenges in seeking stable employment, but also have the opportunity to be hired. Given that some women described making “fast money,” for case managers and service providers, it is important to help normalize employment as being devoid of “fast money” to help women translate their existing skillsets into a legal profession. Women appeared open to various jobs; however, some women described lack of resources related to vocational development. Given these challenges, employment preparation which goes beyond resume and mock interviews is needed. Specifically, at the RDT level it is important to develop a network of employers which are supportive of hiring women, along with adequate employment readiness support. Ultimately, this level of linkage will assist with financial stability described as an area of need.

Program-level challenges included having to wait to search for employment post incarceration. Thus, one intervention includes decreasing the wait time for employment and job seeking which would reduce the number of days to rearrest and reduce recidivism. Additionally, across the focus groups, women described the need to access technology, so that women are able to talk with family, the court system and potential employers. Given access to technology is critical to facilitate employment, connecting with providers and following up with appointments needs to be a consideration in RDTs. Likewise, women described the need to reunite with their families, talk to their families by phone or the desire to find children which have been lost. Further, women described a desire to live with their families at the RDT sites; however, not having a program which provided that level of support was a challenge. Authors have noted that familial and social support is often strained due to incarceration (Wallace et al., 2014) and social bonds change during incarceration (Rocque et al., 2011).

Furthermore, helping women to locate children who are missing is an area of need as many seek to parent and regain missed parenting opportunities. Acknowledging maternal distress and finding effective ways to assist women in processing their emotions and possibly facilitate mothering is important during reentry (Arditti & Few, 2008). A parenting program would include coping, communication, sobriety, healthy relationships, building social/economic capital and building positive relationships with women (Arditti & Few, 2008). Despite some limitations for supporting parenting in RDT sites, the women noted that stable support was present at the RDT sites.

Another important finding is that some women described experiencing past abuse and that drugs provided them with a sense of control. Traumatic life events have been commonly experienced by incarcerated women (Cook et al., 2005; Gilfus, 2002). In one study among 403 incarcerated women, 99% of the sample reported having experienced one traumatic life event (Cook et al., 2005). Scholars have also found that violence experienced by women increase their risk for incarceration (Gilfus, 2002). Further, drug use is a means of self-medication (Khantzian, 1997) in order to address traumatic life experiences which lead to reincarceration (Gilfus, 2002). Women also described the importance of working with staff that have had similar life experiences. Previous research has found peer support models which incorporate paraprofessionals and community health workers (CHW) is an effective delivery of care model (Gordon & Arbuthnot, 1988; Swider, 2002). Incorporating CHWs in RDT settings is a promising avenue for future research with women during the reentry transition.

Policy and Practice Implications

These findings highlight the intersection between individual-level agency, program, and institutional/societal levels during community reentry, reincarceration and homelessness. This subpopulation is unique in that they are currently homeless and residing in an RDT. Therefore, the challenges that they face are greater than those who have a home upon discharge due to the anticipation of homelessness at release, disconnected family, low social support and challenges with housing and employment. Greater access to resources necessitates a concerted effort by RDT providers that are linked with a multi-tiered level of providers which would include housing, healthcare and employers. Likewise, familial reconciliation and parenting support requires training by staff and RDT providers, along with access to workshops and courses which would enable the development of parenting skills, along with working with families and the court system to help reunify families. Given that correctional settings are often hostile places and potentially perpetuate re-traumatization (Mollard & Brage Hudson, 2016), we extend previous recommendations related to the need to provide a gender-sensitive approach wherein the Trauma Process Model (Covington, 2008) is applied to reentry. In particular, centering reentry around trauma-informed care (TIC), an organizational process (Wolf et al., 2014) would include providing trauma-informed services by those working in the facilities by acknowledging trauma, not triggering trauma reactions, modifying behavior of those in RDT facilities to support coping capacity, and self-manage trauma symptoms (Covington, 2008).

Practice implications include training residential providers in trauma-informed approaches and designing a system to educate, empathize, explain and empower participants (Mollard & Brage Hudson, 2016). Provider education would be rooted in defining trauma, understanding the interrelationships of trauma, and recognition of a traumatic response (Mollard & Brage Hudson, 2016). Likewise, it is critical to be empathetic, understand the origin of behavior and focus on a common human experience (Mollard & Brage Hudson, 2016). Next, RDT providers should be transparent about policies and how they are being enforced, what they are doing and when they are doing it which would build trusting provider-patient relationships and minimize distress, while maximizing autonomy (Reeves, 2015). Likewise, it is important to empower participants by providing a sense of responsibility regarding their decisions (Mollard & Brage Hudson, 2016).

At the policy level, connecting academicians with current initiatives such as the Dignity campaign which advocates for reducing the total number of individuals who are incarcerated and providing dignity while incarcerated by educating people and advocating for bills which allow women to have the right healthcare while pregnant and hygiene products while incarcerated is paramount (#cut50, 2018). Second, employing trauma-informed care would include incorporating safety, trustworthiness and transparency, collaboration, empowerment, choice and intersectionality (Bowen & Murshid, 2016). In particular, trauma-informed, drug policy would encompass ensuring those existing jail and prison have health and social safety net programs (Bowen & Murshid, 2016). According to Bowen and Murshid (2016), one way to ensure collaboration and peer support is to engage community health workers to promote choice and reduce barriers to accessing food.

Several limitations related to data collection and analysis should be noted; in particular, this was a convenience sample of women aged 23–53 in two RDT facilities in Los Angeles who had been previously charged with a drug-related offense. This sample included a heterogeneous proportion of women who were on probation and parole, both types of conditional release; specifically, women who have been released from prison are generally on parole, whereas women who have been released from jail are on probation and community supervision (Golder et al., 2014) and there may be distinct differences among resources provided to the parole and probation populations. While every effort was made to have at least six participants in each focus group, at times, it was not possible due to logistics. While previous formative work was based on the voices and perspectives of this population, the CAB was not composed of currently homeless women on parole or probation, rather was composed of individuals whom were working with this population. Further, member checking was not used with currently homeless women on parole or probation; however, results were reviewed and discussed with the CAB and community-based stakeholders to support trustworthiness of the data.

All things considered, the voices and perspectives of formerly incarcerated, homeless women illuminate the importance of facilitators and barriers and their subsequent coexistence. These emergent themes support developing interventions which address individual-level, program and institutional/societal level barriers during the transition through community reentry. This study adds to the extant body of literature by identifying perceptions of barriers and facilitators to community transition preparation at differing levels within the context of individual-level, program-level, and institutional/societal level factors which may exist singularly or co-occur. It is important to be cognizant of these differences and how they impact interrelationships between organizations and policy makers to galvanize support at all levels. In order to create change, it is important to acknowledge facilitators at each level while targeting each barrier in order to enable successful community reintegration and circumvent continued homelessness and reincarceration.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA, grant number 5R34DA035409)

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Benissa E. Salem, University of California, Los Angeles.

Jordan Kwon, University of California, Los Angeles and Azusa Pacific University.

Maria L. Ekstrand, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Elizabeth Hall, University of California, Los Angeles.

Susan F. Turner, University of California, Irvine.

Mark Faucette, Department of Health Services, Housing for Health/Office of Diversion and Reentry Regina Slaughter Amistad De Los Angeles.

References

- #cut50. (2018). #cut50 a Dream Corps Initiative. Retrieved May 9, 2018 from https://www.cut50.org/our_mission [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, Flaherty C, & Ely G. (2010, May 1, 2010). Throwaway Moms: Maternal Incarceration and the Criminalization of Female Poverty. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 25(2), 160–172. 10.1177/0886109910364345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson EM, et al. (2020). “Eliminating gaps in medicaid coverage during reentry after incarceration.” American Journal of Public Health 110(3): 317–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditti J, & Few A. (2008, September). Maternal distress and women’s reentry into family and community life. Family Process, 47(3), 303–321. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18831309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, Glanz J, Long J, Booth RE, & Steiner JF (2012). Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 7(1), 1–9. 10.1186/1940-0640-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C. (2008). An affordable home on re-entry: federally assisted housing and previously incarcerated individuals. National Housing Law Project. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, & Covington S. (2004). Women offenders and the gendered effects of public policy. Review of policy research, 21(1), 31–48. 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00056.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen BA, & Covington S. (2003). Gender-responsive strategies research, practice, and guiding principles for women offenders. National Institute of Corrections. http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS33526 [Google Scholar]

- Bobbitt M, Campbell R, & Tate GL (2006). Safe return: Working toward preventing domestic violence when men return from prison. Vera Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen EA, & Murshid NS (2016). Trauma-informed social policy: A conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. American journal of public health, 106(2), 223–229. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert AM, Sekula LK, Zoucha R, & Cohen SM (2013, September-Oct). Health care needs of women immediately post-incarceration: a mixed methods study. Public Health Nursing, 30(5), 409–419. 10.1111/phn.12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors K, et al. (2020). “Family Member Incarceration, Psychological Stress, and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in Mexican Women (2012–2016).” American Journal of Public Health 110(S1): S71–S77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SL, Smith SG, Tusher CP, & Raiford J. (2005). Self-reports of traumatic events in a random sample of incarcerated women. Women & Criminal Justice, 16(1–2), 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Arsenault D, & Morrison-Beedy D. (1999). Practical advice for planning and conducting focus groups. Nursing research, 48(5), 280–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. (2008). Women and addiction: A trauma-informed approach. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 40(sup5), 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draine J, & Herman DB (2007). Critical time intervention for reentry from prison for persons with mental illness. Psychiatric services, 58(12), 1577–1581. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Anderson MR, Valverde J, Starrels JL, Cunningham CO, Bartlett G, & Valverde J. (2014). Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration Transitions clinic. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(3), 1139–1152. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JJ, Herme M, Wickersham JA, Zelenev A, Althoff A, Zaller ND, Bazazi AR, Avery AK, Porterfield J, Jordan AO, Simon-Levine D, Lyman M, & Altice FL (2013, October). Understanding the revolving door: individual and structural-level predictors of recidivism among individuals with HIV leaving jail. AIDS Behavior, 17 Suppl 2, S145–155. 10.1007/s10461-013-0590-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes CM (2014, March). Nobody’s child: the role of trauma and interpersonal violence in women’s pathways to incarceration and resultant service needs. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 28(1), 85–104. 10.1111/maq.12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M, & Ritter N. (2012). Improving Access to Services for Female Offenders Returning to the Community. Journal of the National Institute of Justice, 269(269), 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gilfus ME (2002). Women’s experiences of abuse as a risk factor for incarceration. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Available at www.vawnet.org. [Google Scholar]

- Golder S, Hall MT, Logan TK, Higgins GE, Dishon A, Renn T, & Winham KM (2014, March). Substance use among victimized women on probation and parole. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(4), 435–447. 10.3109/10826084.2013.844164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DA, & Arbuthnot J. (1988). The use of paraprofessionals to deliver home-based family therapy to juvenile delinquents. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 15(3), 364–378. [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, & Greenwell L. (2007). Treatment needs and completion of community-based aftercare among substance-abusing women offenders. Women’s Health Issues, 17(4), 244–255. 10.1016/j.whi.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall EA, Baldwin DM, & Prendergast ML (2001). Women on parole: Barriers to success after substance abuse treatment. Human Organization, 60(3), 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Herman DB, Conover S, Gorroochurn P, Hinterland K, Hoepner L, & Susser ES (2011). Randomized trial of critical time intervention to prevent homelessness after hospital discharge. Psychiatric services, 62(7), 713–719. 10.1176/ps.62.7.pss6207_0713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner BM, DeJong C, & Cobbina J. (2010). Women Coming Home: Long-Term Patterns of Recidivism. Justice Quarterly, 27(2), 225–254. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual review of public health, 19(1), 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, & Wells K. (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA, 297(4), 407–410. 10.1001/jama.297.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble D, & Bonzcar TP (2017). Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppus15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kajstura A. (2019). Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard review of psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. 10.3109/10673229709030550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallicoat SL (2011). Women and crime: A text/reader (Vol. 10). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mallicoat SL (2014). Women and crime: a text/reader (Hemmens C, Ed. Second ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Mears DP, & Cochran JC (2015). Prisoner reentry in the era of mass incarceration. [Google Scholar]

- Mollard E, & Brage Hudson D. (2016). Nurse-Led Trauma-Informed Correctional Care for Women. Perspectives in psychiatric care, 52(3), 224–230. 10.1111/ppc.12122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ, & Karberg JC (2007). Drug use and dependence, state and federal prisoners, 2004. U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS85621 [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi AM, Srivastava N, Salem BE, Wall S, Kwon J, Ekstrand M, Hall E, Turner SF, & Faucette M. (2016, April-June). Female Ex-Offender Perspectives on Drug Initiation, Relapse, and Desire to Remain Drug Free. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 12(2), 81–90. 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, & Beck CT (2019). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E. (2015). A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues in mental health nursing, 36(9), 698–709. 10.3109/01612840.2015.1025319?needAccess=true [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie BE, Freudenberg N, & Page J. (2001). Reintegrating women leaving jail into urban communities: a description of a model program. Journal of Urban Health, 78(2), 290–303. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3456359/pdf/11524_2006_Article_27.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocque M, Bierie DM, & MacKenzie DL (2011, August). Social bonds and change during incarceration: testing a missing link in the reentry research. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(5), 816–838. 10.1177/0306624X10370457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Salem BE, Nyamathi A, Idemundia F, Slaughter R, & Ames M. (2013, January-Mar). At a crossroads: reentry challenges and healthcare needs among homeless female ex-offenders. Journal of forensic nursing, 9(1), 14–22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24078800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury EJ and Van Voorhis P. (2009). “Gendered pathways: A quantitative investigation of women probationers’ paths to incarceration.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 36(6): 541–566. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer W. (2019). “Who’s helping the 1.9 million women released from prisons and jails each year?”. from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/07/19/reentry/. [Google Scholar]

- Scroggins JR, & Malley S. (2010). Reentry and the (Unmet) Needs of Women. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 49(2), 146–163. 10.1080/10509670903546864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton AK (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfield R, Mowen TJ, Napolitano L, & Boman JH (2020). Examining Change in Family Conflict and Family Violence After Release From Prison. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(6), 668–687. [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, et al. (2019). “Staying Out: Reentry Protective Factors Among Rural Women Offenders.” Women & Criminal Justice 29(6): 368–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swider SM (2002). Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: an integrative literature review. Public Health Nursing, 19(1), 11–20. 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Sentencing Project. (2015). Incarcerated women and girls. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/incarcerated-women-and-girls/ [Google Scholar]

- To MJ, Palepu A, Matheson FI, Ecker J, Farrell S, Hwang SW, & Werb D. (2017). The effect of incarceration on housing stability among homeless and vulnerably housed individuals in three Canadian cities: A prospective cohort study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 107(6), 550–555. 10.17269/cjph.107.5607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan JM, et al. (2019). “Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health.” BMC Med 17(1): 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2014). Poverty Highlights in 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2015 from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/about/overview/ [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Eliason MJ, Freudenberg N, & Barnes M. (2009). Nowhere to go: How stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 4(1), 1–10. 10.1186/1747-597X-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D, Fahmy C, Cotton L, Jimmons C, McKay R, Stoffer S, & Syed S. (2014, August 25). Examining the Role of Familial Support During Prison and After Release on Post-Incarceration Mental Health. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 10.1177/0306624X14548023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MR, Green SA, Nochajski TH, Mendel WE, & Kusmaul NS (2014). ‘We’re Civil Servants’: The Status of Trauma-Informed Care in the Community. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(1), 111–120. 10.1080/01488376.2013.845131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]