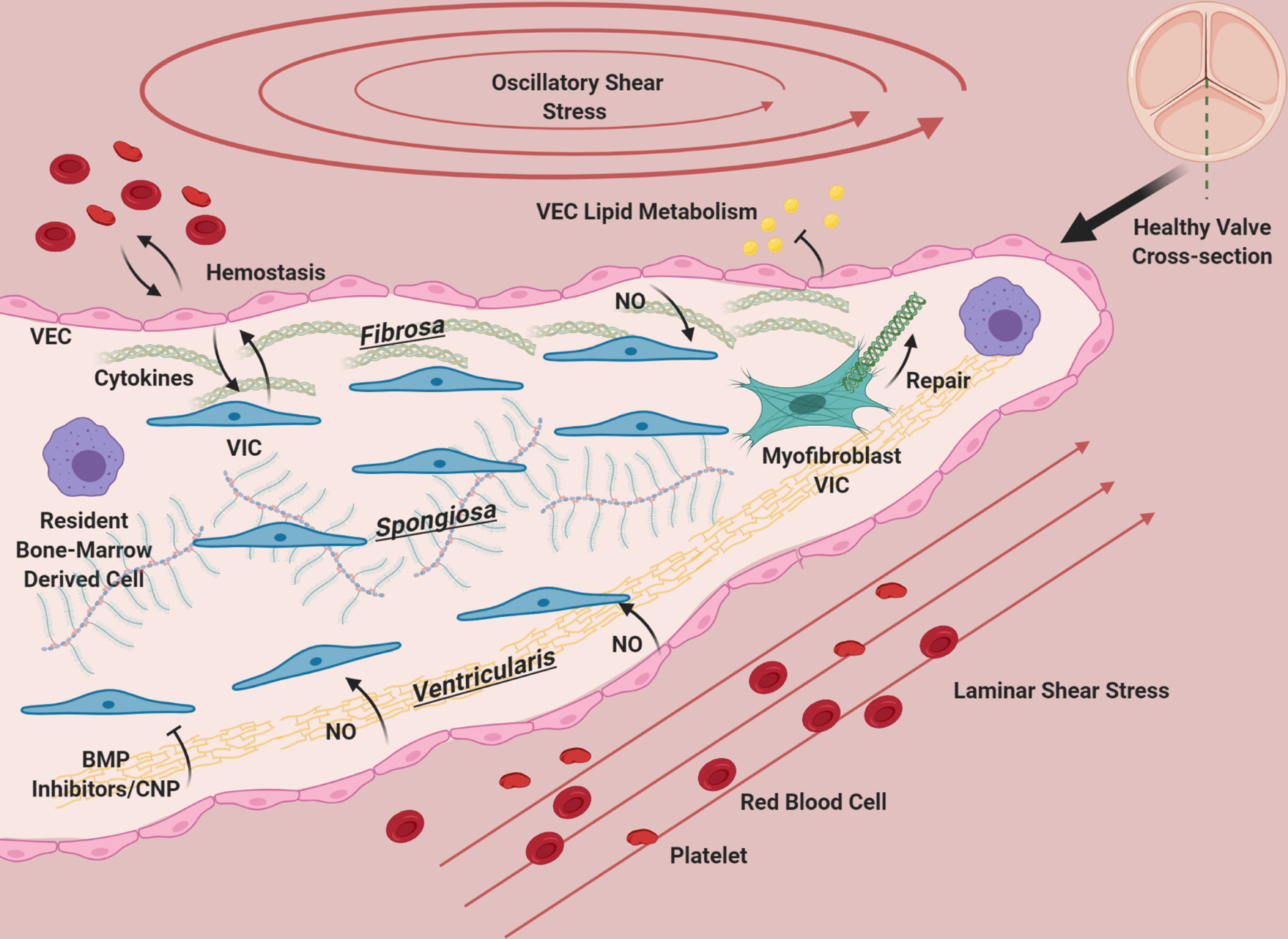

Figure 2. The aortic valve during homeostasis (cross-section).

The aortic valve has three layers: the fibrosa, consisting primarily of circumferentially oriented collagen, the spongiosa, consisting primarily of GAGs, and the ventricularis containing radially-aligned elastin. A diverse population of interstitial cells broadly defined as VIC inhabit these layers in the interstitium of the valve (blue) and become activated to remodel the ECM of the valve as needed (green). VEC line the valve and provide a barrier from the blood, preventing clotting, mediating infiltration of lipids, nutrients, and modulating extravasation of inflammatory cells. VEC (pink) promote quiescence in VIC through nitric oxide signaling, and VIC and VEC also communicate with cytokines. Osteogenic inhibitors such as BMP inhibitors and CNP from the ventricularis endothelium likely maintain homeostasis by preventing VIC activation. The homeostatic valve also contains resident immune cells (purple), whose functions are just beginning to be uncovered. The ventricularis of the valve experiences laminar shear, while the fibrosa has oscillatory flow. The valve is constantly under tension/compression as the valve opens and closes, and resists pressure. The ECM composition of the valve and cellular maintenance ensures that it remains flexible, strong and compliant so that it is durable over a human lifespan.