Abstract

Spontaneous perforation of the esophagus is an emergency that requires early diagnosis and management. It may be fatal and delay in treatment can cause an increase in morbidity and mortality. Despite of being very rare in infants, we have to be watchful whenever we encounter signs and symptoms related to it. Only 7 cases of spontaneous esophageal perforation in infants have been report in the literature to the best of our knowledge. Here we are reporting a rare case of spontaneous esophageal rupture in an infant.

Keywords: Esophageal perforation, Spontaneous perforation, Boerhaave’s syndrome, Esophagogram

Introduction

Spontaneous esophageal perforation or ‘Boerhaave’s Syndrome’ is a rare catastrophe and its precise etiology is unclear. It is a clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic challenge for clinicians. The first account of spontaneous esophageal perforation was given by the Dutch physician Boerhaave in 1724 [1]. Spontaneous perforation in neonates and infants accounts for 4% of all reported cases [2]. The most common site is the lower end of esophagus. Here we are presenting an unusual case of spontaneous esophageal rupture in a 7-month-old infant which is a rare age of presentation.

Case Report

A seven-month-old male child was referred to our institution with respiratory distress and symptoms of septicemia. He was diagnosed to have esophageal perforation with mediastinitis and right hydro-pneumothorax, for which intercostal tube was placed. He was on conservative management for the last one month. On interrogation, it was revealed that the child initially presented with symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection, fever, cough and later with respiratory distress. Initial chest x-ray showed left hydro-pneumothorax. Intercostal tube drainage was performed at the primary health care center where he was first taken for treatment. A repeat x-ray chest after 48 h revealed empyema on right side as well, hence intercostal tube drainage was now placed on right side also. The child improved symptomatically in a week and oral feeding was initiated but it was observed that turbid aspiration increased in the right intercostal tube. The patient continued to be febrile, hence oral paracetamol syrup was administered. Parents reported sudden change in color of the aspirate to be pink on paracetamol syrup ingestion.

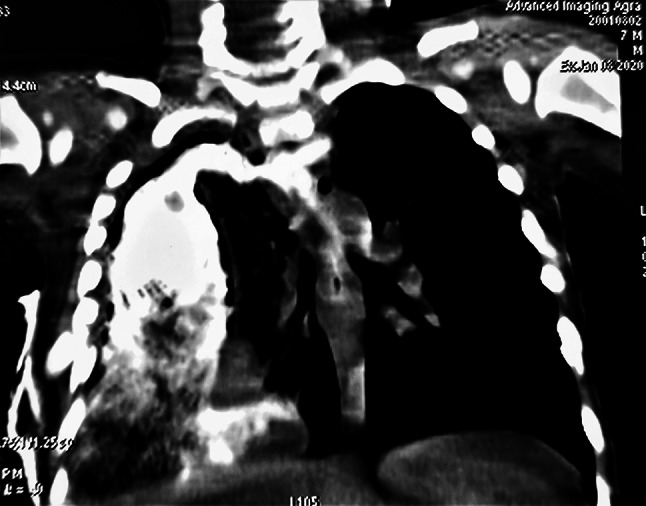

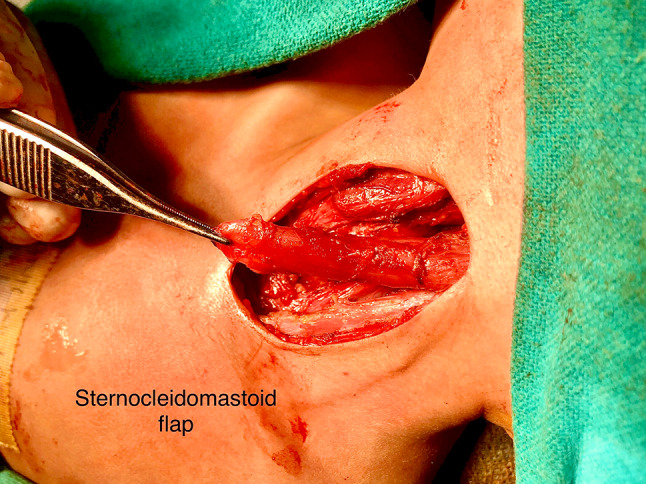

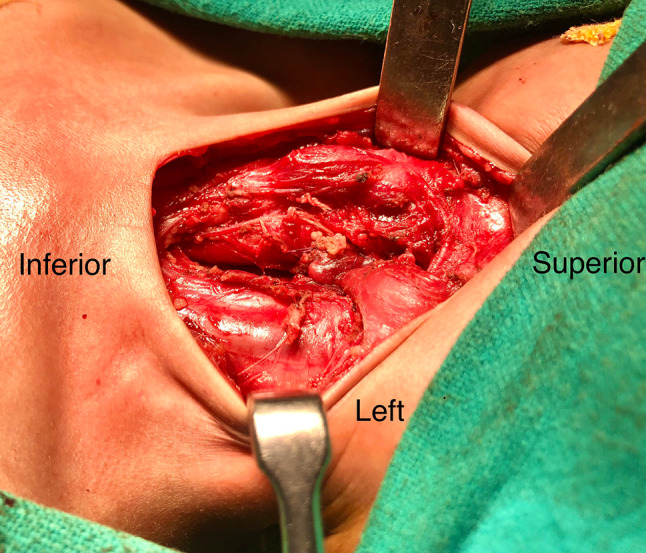

An urgent CECT neck and thorax was advised which revealed esophageal perforation at C6–C7 level (Fig. 1) following which the child was referred to our center. The patient was initially stabilized with parenteral antibiotics and nutrition. Later on, upper GI endoscopy was advised but the site of esophageal perforation could not be located and hence conservative management was continued. After a considerable period of conservative management, as the general condition of the patient did not show signs of improvement, upper GI contrast study was planned which showed perforation at C6–C7 level with dye extravasating into the right pleural space (Fig. 2). Surgical exploration was then planned. On exploration through left cervical approach, a single perforation of about 1 × 0.5 cm size was found at left postero-lateral aspect of cervical esophagus (Figs. 3 and 4), which was repaired in two layers (Figs. 5 and 6) and left sternocleidomastoid muscle flap was used (Figs. 7 and 8) to further support the prevention of fistula. The child was kept on nasogastric tube feeding for 10 days. Then the sutures were removed and upper GI contrast study (Fig. 9) and plain X-ray of chest were repeated that showed no contrast leakage or any other abnormality. The histopathology of margins of perforation reported ulceration and necrosis of the superficial mucosa along with mild infiltration with acute and chronic inflammatory cells and no evidence of eosinophilic esophagitis. The child was gradually started with oral feeding and was well till last postoperative follow up of 3 months.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative CT scan with oral contrast

Fig. 2.

Preoperative esophagogram

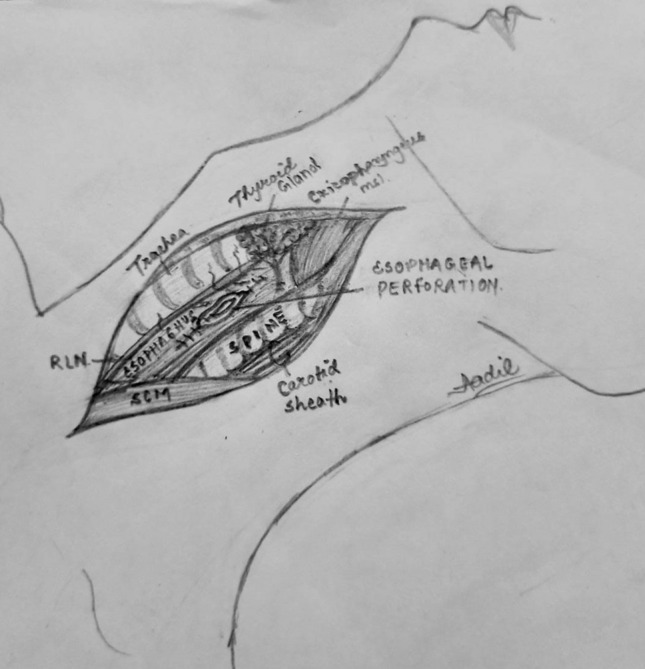

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the perforation site

Fig. 4.

Esophageal perforation

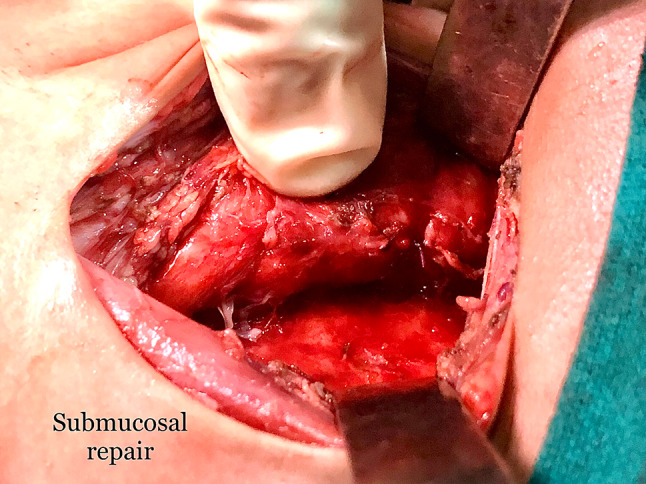

Fig. 5.

Submucosal repair

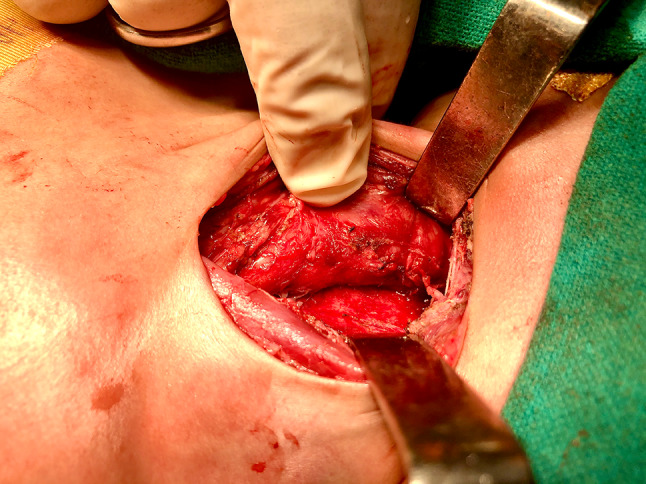

Fig. 6.

Repair of muscular layer

Fig. 7.

Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap

Fig. 8.

Flap repair

Fig. 9.

Postoperative esophagogram

Discussion

In the era of endoscopy, there has been a shift in the etiology of esophageal perforation in children, from spontaneous esophageal rupture (60%) to iatrogenic (75%) [3–5]. Majority of the perforations in children, irrespective of mechanism, are proximal in location (hypopharynx, cervical and thoracic esophagus) [6]. However, in case of spontaneous esophageal perforation also known as Boerhaave’s syndrome, the site of rupture is usually lower esophagus.

Spontaneous ruptures are usually strain induced by vomiting and retching. Usual site is left postero-lateral wall of distal esophagus which is thinnest area of esophagus. sudden increase in intra luminal pressure due to increase abdominal pressure at delivery, pre-existing weakness in the esophageal wall (either congenital or from a perinatal ischemic event), perinatal hypoxemia, peptic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux cause longitudinal rent in neonates [7, 8].

It is rare especially in cervical region in infants. In our case, a seven months old infant suffering from respiratory tract infection with respiratory distress and developed pneumothorax and empyema which were manifestations of cervical esophageal perforation. So, it raises the question what was the cause of cervical esophageal perforation? Was there any anatomical weakness in cervical esophagus or there was a pre-existing inflammatory condition? The portion of cervical esophagus in cricopharyngeal region is formed by the inferior constrictor and cricopharygeous muscles at the level of the C5–C6 vertebrae, the posterior esophageal mucosa is covered only by fascia. This anatomically weak area is named as Lannier’s triangle [9]. Intrinsic anatomic abnormality or dysfunction present within the esophageal wall may be the cause of spontaneous esophageal perforation [10].

A recently recognized clinical entity, eosinophilic esophagitis is mentioned as a cause of spontaneous esophageal rupture in several studies [11–13]. Cricopharyngeal spasm not associated with trauma has also been observed as a distinct entity in the newborn [11]. In our case esophagitis associated cricopharyngeal spasm could be the cause of spontaneous cervical esophageal perforation.

Most common manifestations of cervical esophageal perforation (EP) are respiratory distress and subcutaneous emphysema. Clinical presentation of EP depends on etiology, site of perforation, size of perforation, degree of contamination, time elapsed after perforation and presence of other associated injury or pathology. Most common symptoms are pain, fever, dysphagia, dyspnea, vomiting and anorexia; and common signs are tachycardia, tachypnea, cyanosis, subcutaneous emphysema seen in 30% of thoracic EP and 60% cervical EP, cardiac crunch (Hamman’s sign), chest hypersonasity or dullness and crepitation in neck region due to presence of air in soft tissue.

A classical triad of vomiting, chest pain and surgical emphysema is known as MACKLER’S TRIAD. X-ray chest is the initial investigation which reveal indirect evidence of perforation as pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, air–fluid level in mediastinum, widening of mediastinum, pneumothorax, hydrothorax, hydropneumothorax and it can be normal in 12–33% of cases and they cannot identify the location of perforation [3] but these findings are nonspecific until unless there is history of trauma or instrumentation.

Contrast study is the standard tool for diagnosis. Water soluble agent is used. Esophagogram suggests primary area of perforation and communication of leak with mediastinum, pleural space or peritoneal space. In 10% of cases there is a probability of false negative results.

CT thorax demonstrates precise location, aids in atypical presentation, in cases of negative contrast study, re-evaluation after initial therapy, extra luminal air–fluid and esophageal thickening.

Rigid or flexible Esophagoscopy is another tool which can help in diagnosis. It is required when CT findings are indeterminate. In our case upper GI endoscopy was not conclusive and according to some authors, endoscopy is less accurate than contrast study; not useful in diagnosing cervical perforation and there may be chances of rather enlargement of the perforation [3, 8].

The management of EP depends on duration of perforation, onset of symptoms, etiology, site of and size of perforation [4–7, 12]. If patient’s condition is recognized early and therapy instituted within 24 h following perforation, the mortality rate is in the range of 10%. Delayed diagnosis (> 24 h) is associated with an increased mortality rate of 50% or greater [6].

The thoracic part of the esophagus is common site of endoscopic perforation. In case of cervical esophageal perforation, the clinical feature may not be life threatening in comparison to those of thoracic perforation, for which mortality rate can be as high as 40% [5, 6]. But this is not true for large spontaneous cervical esophageal perforation, where hydropneumothorax, empyema already developed and patient’s presentation is delayed as occurred in our case.

Patient with iatrogenic perforation generally have better outcome than those caused by spontaneous rupture or occur after surgical anastomosis [6, 7]. According to our case and previous studies, all cases of spontaneous cervical esophageal perforations are diagnosed late and the clinical course and outcomes suggest that they are difficult to manage conservatively and ultimately land up to surgical intervention.

As per the experience of our case and other available research, the site of esophageal perforation is most important factor affecting outcome of patient, cervical location being more favorable than thoracic [5]. On the other hand, we feel that cervical perforations, if large are more life threatening and difficult to manage because of difficult surgical access and ineffective tissue coverage while large thoracic perforation can be effectively managed by surgery.

As per our new suggested classification, a spontaneous cervical perforation can be divided into post emetic and others which are further divided into small (< 1 cm) and large (> 1 cm) perforation.

- Cervical/cricopharyngeal

- Spontaneous

- Post emetic

-

OthersEsophagitis—small (< 1 cm) or large (> 1 cm)Esophageal dysfunction—small (< 1 cm) or large (> 1 cm)

- Traumatic

Thoracic

Lower esophageal

The plan of management of spontaneous cervical esophageal perforation depends on the size of perforation. Small perforations can be managed conservatively but the larger ones definitely require surgical repair. In literatures there are very few studies which reflect esophageal perforation in infants and that also is further rare in cervical part.

In a study of Morzaria et al., there are 3 cases of infants with hypopharynx/cervical esophageal perforation without known cause, which can be placed in spontaneous cervical esophageal perforation. All these cases are managed conservatively. But in this study the duration of diagnosis, size of perforation and the duration of treatment along with outcome are not taken into consideration, which are taken in account in our case and review of literature [4].

The study by Engum et al. included 5 cases of cervical esophageal perforation, of which only one case with unknown cause [6]. This case was diagnosed late and managed by primary closure, with an abscess as post-operative complication. In this study they consider the time of presentation as early (< 24 h) and late (> 24 h), which is used as prognostic factor in case of cervical esophageal perforation with known etiology but in case of spontaneous cervical perforation, the symptoms are vague and diagnosis is difficult without contrast study. So, we consider the duration of diagnosis as early and late diagnosis rather than timing of presentation.

The study by Sarin et al. describes 2 cases of pharyngoesophageal perforation with pseudo-diverticulum in neonates without known cause which were managed by surgical intervention [10]. One was managed by cervical exploration and repair with a good outcome but the second case was diagnosed after thoracotomy and could not survive. The presence of pseudo-diverticulum in neonate suggests congenital weakness in pharyngoesophageal wall which may be the cause of spontaneous esophageal perforation as per our hypothesis. We also support aggressive surgical intervention and believe that it might be a better alternative to conservative management in cases of spontaneous cervical esophageal perforation in infants.

In the report of Eklof et al. [14], the neonate had an opening in posterior wall of upper esophagus on esophagoscopy. Thoracotomy was suggestive of submucosal esophageal tract. Author considered it as spontaneous rupture as in our case.

Conclusion

Despite the difficulty in diagnosis and the high morbidity and mortality associated with Boerhaave’s syndrome, patients can survive if diagnosed and managed early without any time lag.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed in the conceptualization, in the preparation and final disposition of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There has been no financial support and no conflict of interest in this study.

Informed Consent

An informed consent was taken from parents of the patient as well as first hand relatives.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Derbes VJ, Mitchell RE., Jr Herman Boerhaave Atrocis, nec descripti prius, morbi historia: the first translation of the classic case report of rupture of the esophagus, with annotations. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1955;43:217–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunebaum M, Horodniceanu C, Wilunsky E, Reisner S. Iatrogenic transmural perforation of the esophagus in the preterm infant. Clin Radiol. 1980;31:257–261. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(80)80211-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamawandi AM, Baram A, Ramadhan AA, Karboli TA, Taha AY, Anwar A (2014) Esophageal perforation in children: experience in Kurdistan Center for Gastroenterology and Hepatology/Iraq. Open J Gastroenterol 4:221–227

- 4.Morzaria S, Walton JM, MacMillan A. Inflicted esophageal perforation. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(6):871–873. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govindarajan KK. Esophageal perforation in children: etiology and management, with special reference to endoscopic esophageal perforation. Korean J Pediatr. 2018;61(6):175. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2018.61.6.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engum SA, Grosfeld JL, West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LT, Vaughan WG. Improved survival in children with esophageal perforation. Arch Surg. 1996;131(6):604–611. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430180030005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baum ED, Elden LM, Handler SD, Tom LW. Management of hypopharyngeal and esophageal perforations in children: three case reports and a review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87(1):44–47. doi: 10.1177/014556130808700115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modi A, Mathur NB, Sarin YK. Spontaneous neonatal esophageal perforation. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37(8):901–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley DS (2020) Esophageal perforation in the newborn. In: Pediatric surgery: general principles and newborn surgery, pp 705–711

- 10.Sarin YK, Sinha A. Esophageal perforation in infancy and childhood: our experience. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2001;6(2):14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SB, Kuhn JP. Esophageal perforation in the neonate: a review of the literature. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130(3):325–329. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1976.02120040103020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones WG, Ginsberg RJ. Esophageal perforation: a continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53(3):534–543. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90294-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber TR (2012) Esophageal rupture and esophageal perforation, Chap 68. In: Coran AG (ed) Pediatric surgery, 7th edn

- 14.Eklof O, Lohr G, Okmian L. Submucosal perforation of the esophagus in the neonate. Acta Radiol. 1969;8:1987. doi: 10.1177/028418516900800210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]