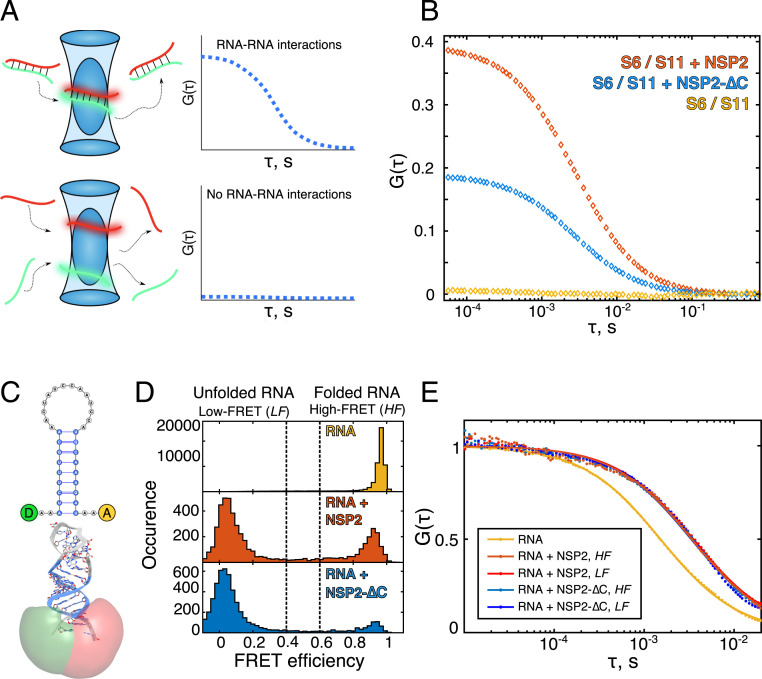

Fig. 2.

The NSP2 CTR is required for efficient RNA–RNA matchmaking yet limits RNA unwinding. (A) Single-molecule assays to probe RNA–RNA interactions between partially complementary fluorescently labeled RNAs S6 (green) and S11 (red). Upon strand annealing, differently labeled transcripts codiffuse (shown as a duplex within the blue confocal volume). Such interactions result in a nonzero amplitude of the CCF and thus directly report the fraction of interacting RNAs. A CCF amplitude G(τ) = 0 indicates that the two RNA molecules diffuse independently and are not interacting. (B) An equimolar mix of S6 and S11 RNAs were coincubated in the absence (yellow) or presence of either NSP2 (orange) or NSP2-∆C (blue). While the two RNAs do not interact, coincubation with NSP2 results in a high fraction of stable S6:S11 complexes. In contrast, coincubation of S6 and S11 with NSP2-∆C results in twofold reduction of the fraction of S6:S11 complexes. (C) Schematics of the RNA stem-loop used for the smFRET studies of helix-unwinding activity. The FRET donor (D, green) and acceptor (A, red) dye reporters (Atto532 and Atto647N) and their calculated accessible volumes (green and red, respectively) are shown. (D) smFRET efficiency histograms of the RNA stem-loop alone (Top, yellow) in the presence of 5 nM NSP2 (Middle, red) or 5 nM NSP2-∆C (Bottom, blue). (E) A species-selective correlation analysis was performed on the high FRET (HF) and low FRET (LF) species of RNA stem-loops bound to NSP2 (orange) and NSP2-∆C (blue). All FCS analyses were performed on the smFRET data shown in D.