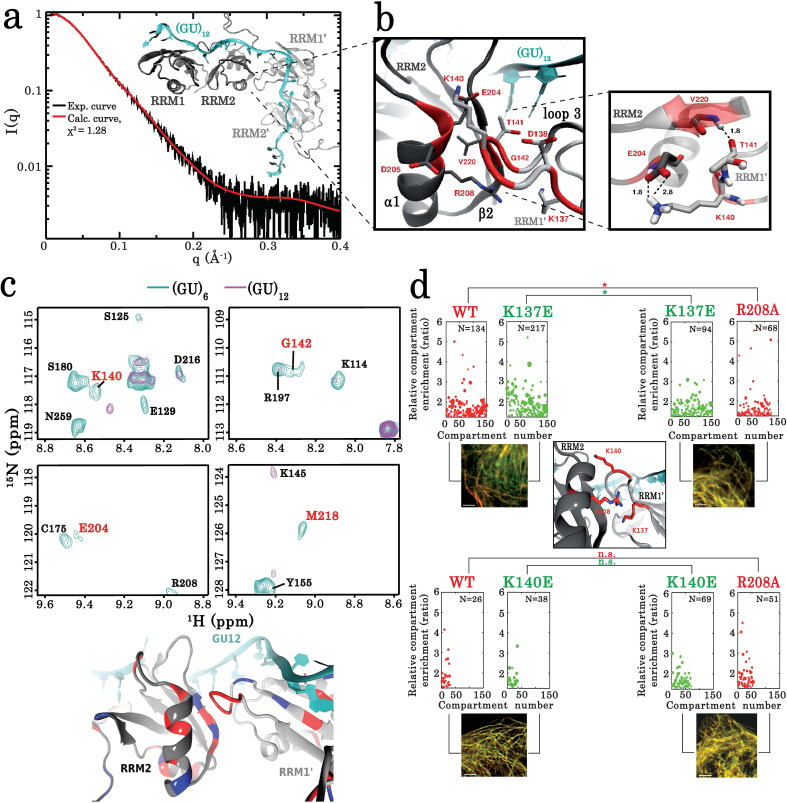

Figure 5. Key residues governing the RRM-dependent TDP-43 multimerization on RNA targets.

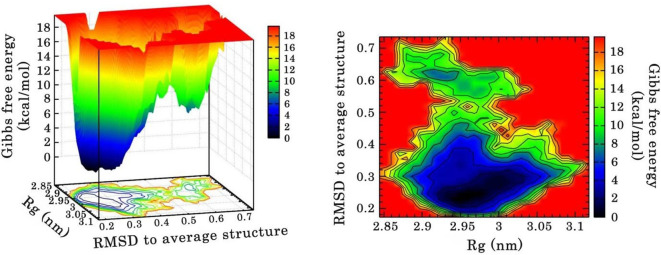

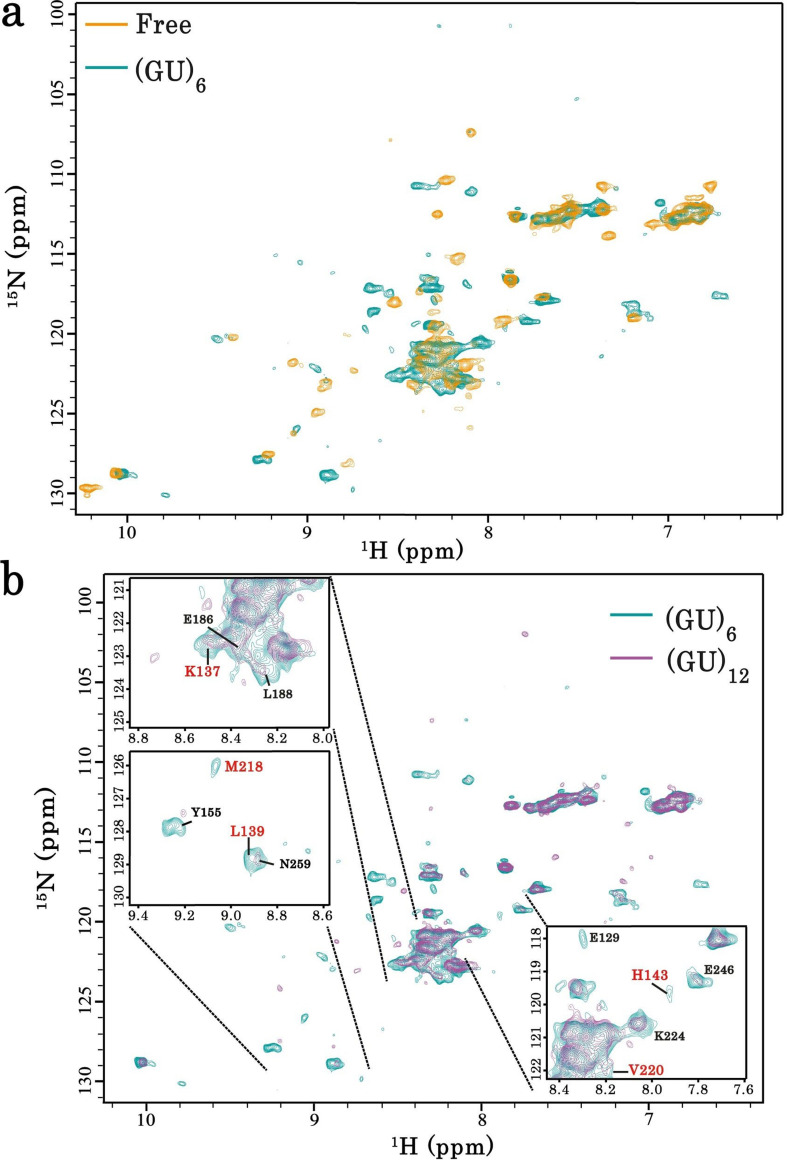

(a) Superimposition of calculated (red curve) and experimental (black dots) SAXS curves corresponding to RRM1–2 bound to (GU)12. SAXS curves were calculated from all-atoms model using the program GAJOE from the suite EOM. The corresponding χ2 values are indicated. The inset is a 3D representation of the model built using MD simulations from which the conformational state at equilibrium was considered. (b) Zoom in on the 3D model corresponding to the RRM1–2 bound to (GU)12 showing the protein-protein interface created by the interaction of residues located in the α -helix α1 and β-strand β2 belonging to the RRM2 (first monomer) with residues located in the RRM1 loop 3 (second monomer). Interacting couples are highlighted in red and interaction bonds are shown by dotted lines. Numbers in black reflect the distance (Å). (c) Upper panel shows a zoom in on the superimposed 1H-15N SEA-HSQC spectra (see full NMR spectra in Figure 5—figure supplement 5) of 15N-labeled RRM1–2 bound to (GU)6 (turquoise) or to (GU)12 (magenta). The residues present at RRM1–2 dimerization interface (highlighted in red) are no longer exposed to the solvent. Lower panel shows the global changes derived from SEA-experiment in solvent-exposed amides located at the protein-protein interface which are mapped on the 3D structure obtained from MD simulations (blue: exposed, red: not exposed). (d) As in Figure 3c, the microtubule bench assay was used to quantify the compartmentalization of different forms of TDP-43 co-expressed in HeLa cells. Center panel: view on the close proximity between R208 in RRM2 (first monomer) and K137 in RRM1 (second monomer). Upper panel shows a demixing phenotype between wild-type and K137E TDP-43. In contrast, R208 better mixes with K137E than wild-type TDP-43. Bottom panel, as a control, this behavior is not observed in the case of K140E. Scale bar: 10 µm. p<0.05*; p<0.01** (paired two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). n.s. non-significant. N, number of compartments.