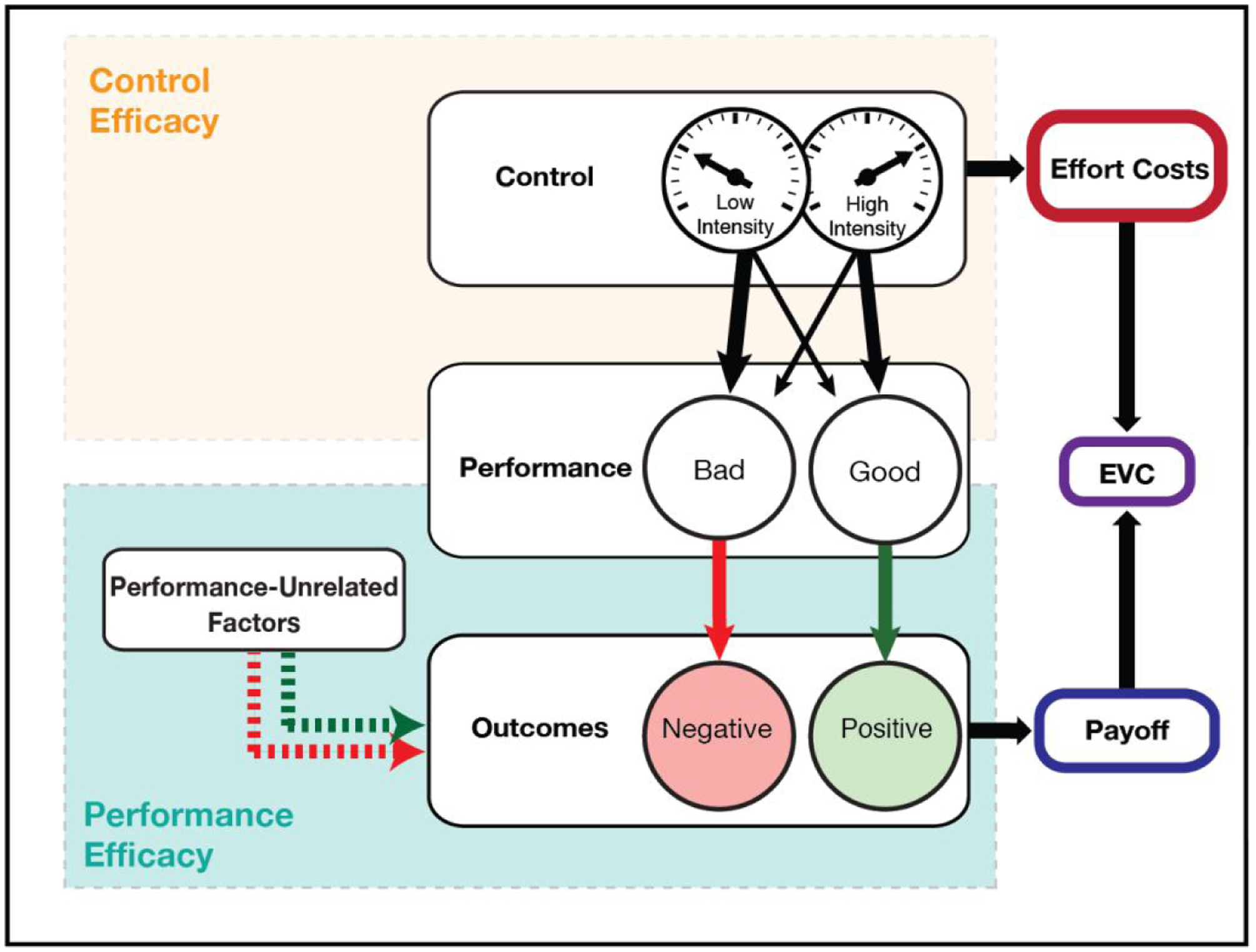

Figure 1.

The Expected Value of Control (EVC) model proposes that we determine how to exert mental effort by weighing the costs and benefits of allocating cognitive control in a particular way given their current situation. Cognitive control is allocated according to two factors: the types of control being engaged (e.g., attention to specific features of a task, suppression of inappropriate responses) and how intensely to engage each of these. The model assumes that we experience greater intensities of control as more mentally effortful, and therefore more costly (for a discussion of potential sources of these costs, see Shenhav et al., 2017). To determine the overall value of a given control allocation (EVC) given the current context, this effort cost is weighed against the expected payoff for exerting effort. This payoff is determined by the estimated expected outcomes for exerting effort (e.g., monetary gain/loss, social approval/admonishment), weighed by the extent to which these outcomes change with increasing control (i.e., effort). The payoff is further determined by whether control matters for attaining these outcomes. If greater control has little bearing on one’s performance (low control efficacy, e.g., if the task is too difficult or is beyond our ability) or if outcomes are expected to be largely determined by performance-unrelated factors like a person’s social status (low performance efficacy), then control will be deemed less worthwhile. Though not shown here, each of these components can have some uncertainty around it - for instance, even when outcomes are completely determined by performance, there may be some uncertainty about whether a given outcome will come to pass.