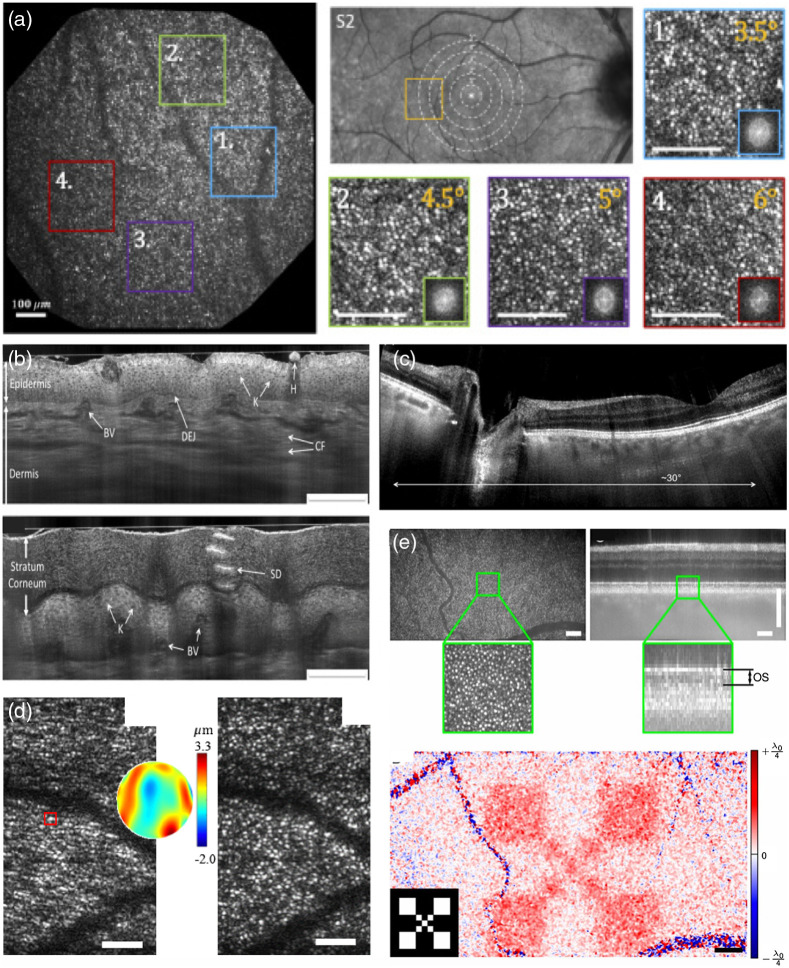

Fig. 2.

Examples for FF and LF OCT. (a) High-resolution large FOV retinal FFOCT. Panels 1 to 4 visualize the cone photoreceptor mosaic at different eccentricities as shown in panel S2 (scale bar ). Reproduced from Ref. 42., © 2020 Optical Society of America (OSA). (b) TD LF OCT of human skin, using dynamically aligned confocal and coherence gating (K, keratinocytes; DEJ, dermal–epidermal junction; SD, sweat duct; H, hair; CF, collagen fibers; BV, blood vessels. Scale bars: ). Reproduced from Ref. 41, © 2018 OSA. (c) Retinal imaging with LF SS OCT at 600 kHz equivalent A-scan rate. Reproduced from Ref. 39, © 2015 OSA. (d) Computational adaptive optics for in vivo high-resolution retinal imaging (left: uncorrected enface slice from photoreceptor layer; center: reconstructed wavefront error; and right: corrected enface slice by phase conjugation of the wavefront error to the pupil plane phase; error bars ). Adapted from Ref. 43. (e) Advantage of FFOCT phase stability for functional OCT assessment of photoreceptor response (upper row: enface plane at OS photoreceptor layer of recorded volume together with tomogram; lower row: response measured as phase change over time after light stimulus onset; inlay shows the actual stimulus mask). Adapted from Ref. 44.