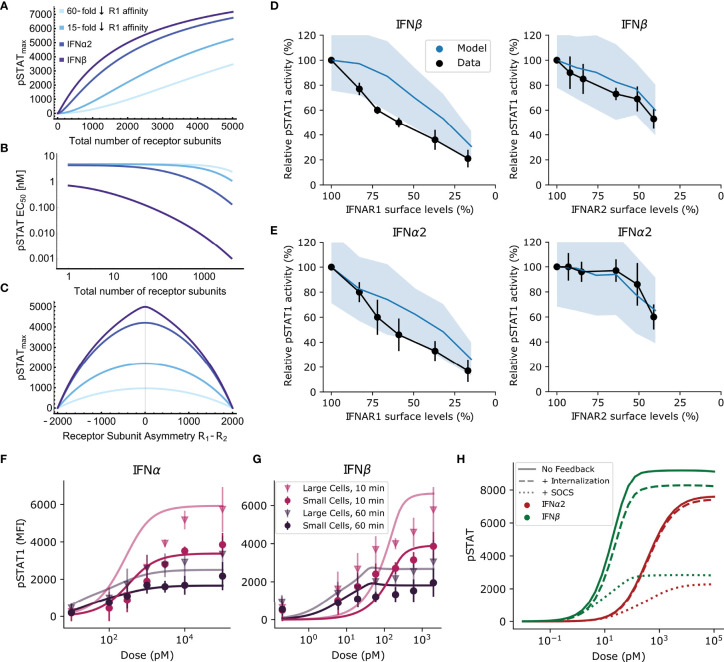

Figure 3.

Receptor expression levels can regulate signal specificity. (A, B) The equilibrium model predicts how pSTATmax (A) and pSTAT EC 50 (B) vary with the total number of receptor subunits on the cell surface. From violet to lightest blue, lines correspond to high affinity IFNβ, lower affinity IFNα2, and IFNα2 mutants with 15-fold and 60-fold lower IFNAR1 affinity, respectively (see text). (C) The dependence of the response on the difference in expression of R1 and R2 subunits for each of the IFN subtypes from A&B. The results in (A–C) are similar for the computational model (not shown); see text. (D, E) pSTAT1 levels following siRNA transfection to knockdown IFNAR1 or IFNAR2 and subsequent stimulation for 45 minutes with 200 pM of IFN. Black: Western blot band intensity measurements; Blue: predicted response from model. Responses are normalized by maximum response. Model uses measured human IFN affinities and mean receptor density between 0.1 and 1 molec. μm-2, consistent with measurements for WISH cells (10). (F, G) Points: Experimental flow cytometry data from mouse B cells with one std. dev. Lines: simulated average pSTAT responses for IFNα2 (F) and IFNβ (G) using the same model parameters as . More copies of IFNAR are expressed in large cells, but no significant difference between the maximum pSTAT response to IFNα2 and IFNβ is observed. (H) Solid lines: simulated pSTAT dose-response curve at 60 minutes without any negative feedback (i.e., setting SOCS1 binding and receptor internalization rates to zero). Dotted lines: the effect of SOCS1. Dashed lines: the effect of receptor internalization. In both cases the dose-response curve is diminished by these negative feedbacks. The difference in pSTATmax between IFNα2 (red) and IFNβ (green) remains constant with the action of SOCS1 inhibition while the difference between IFNα2 and IFNβ is diminished by receptor internalization.