Abstract

Background

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (W. somnifera) is a herb commonly known by its English name as Winter Cherry. Africa is indigenous to many medicinal plants and natural products. However, there is inadequate documentation of medicinal plants, including W. somnifera, in Africa. There is, therefore, a need for a comprehensive compilation of research outcomes of this reviewed plant as used in traditional medicine in different regions of Africa.

Methodology

Scientific articles and publications were scooped and sourced from high-impact factor journals and filtered with relevant keywords on W. somnifera. Scientific databases, including GBIF, PubMed, NCBI, Google Scholar, Research Gate, Science Direct, SciFinder, and Web of Science, were accessed to identify the most influential articles and recent breakthroughs published on the contexts of ethnography, ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and commercialization of W. somnifera.

Results

This critical review covers the W. somnifera ethnography, phytochemistry, and ethnomedicinal usage to demonstrate the use of the plant in Africa and elsewhere to prevent or alleviate several pathophysiological conditions, including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, reproductive impotence, as well as other chronic diseases.

Conclusion

W. somnifera is reportedly safe for administration in ethnomedicine as several research outcomes confirmed its safety status. The significance of commercializing this plant in Africa for drug development is herein thoroughly covered to provide the much-needed highlights towards its cultivations economic benefit to Africa.

Keywords: Africa, Commercialization, Ethnobotany, Ethnomedicine, Medicinal Plant, Pathophysiology, Pharmaceutics, Phytochemistry, Withania somnifera

Background

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (W. somnifera) is one of the most popular medicinal plants of great importance, used in Africa and the world at large. It is among the 85 most prominent African medicinal plant species of international trade per surge in research publications of over 1767 within the last decade (VanWyk 2015). This plant is a member of Solanaceae, a family with 84 genera and about 3000 species that are diversely distributed throughout the world (Mirjalili et al. 2009). Withania is a genus with species that are shrubs, sub-shrubs, or woody herbs. W. somnifera is an ecologically and economically important plant that is as old as Ayurvedic medicine, with millennia of usage as one of the essential plants used in Ayurvedic medicine, the Mediterranean region, and Orientalis. It is a widely distributed plant mainly in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe. In India, it is readily available via cultivation and in the wild agricultural land; and aside from being medicinal, it is also used as bioremediation for phytoextractions (Burkill 1985; Abhilash et al. 2008; Singh and Kumar 2011).

In Africa, W. somnifera exists in several countries, including South Africa, Lesotho, Sudan, South Sudan, Djibouti, Egypt, Tanzania, Swaziland, Mali, Nigeria, Liberia, and Congo (Burkill 1985; Iwu 2014; Naveen et al. 2015). W. somnifera is reported to be indigenous to South Africa, where it is commonly used as a sedative and hypnotic, and also regarded to be effective against numerous ailments in southern Africa, including Lesotho (Burkill 1985; Dold and Cocks 2000). Different parts of the plant are used for various purposes; for example, ointment from leaves and berries is applied to treat cuts, wounds, abscesses, and inflammation. The leaf decoction is also employed to treat haemorrhoids and rheumatism (Idowu and Wilfred 2018). The W. somnifera root contains over 35 bioactive molecules that account for its multi-properties. The plant root is used in traditional medicine as a popular supplement, with supposed benefits that include lessening anxiety and stress (Vijay et al. 2018). In addition to its high antioxidants content, the consumption of the roots improves cardiovascular health, reduces swelling and stress, strengthens heart muscles, regulates cholesterol, and reduces hair loss in the human body (Mamta and Vijaya 2018). Moreover, the roots have also been used for veterinary purposes to treat cattle. A decoction of cooked roots and leaves fed to sheep, cows, and buffalo enhances milk production, while it is also used as an antipyretic and sexual tonic (Aziz et al. 2018a). It is also a rich source of both micro- and macro-nutrients, including iron, magnesium, phosphorous, copper, zinc (Sangita and Alka 2016). Additionally, W. somnifera root extracts are common trade goods in the cosmetics and personal care industries, such as skin conditioners, shampoos, and antiwrinkle agents (Sakamoto et al. 2017). In Egypt, Djibouti, and Ethiopia, people widely use the plant to treat Alzheimer’s disease, bronchitis, and malaria (in combination with other plants) (Hassan-Abdallah et al. 2013; Alebie et al. 2017; Rahma et al. 2017).

W. somnifera is one of the most essential ethnomedicinal herbs in Ayurveda medicine due to its wide range of therapeutic actions (Singh et al. 2011). The ethnomedicinal usages of W. somnifera (Table 1) suggest the significance of the plant for further pharmacological scientific research against several pathophysiological conditions. Noteworthy, no mutagenicity and genotoxicity have been reported for W. somnifera, and thus, the plant has been cleared as a safe use for the management of neurocognitive disorders, diabetes, arthritis, and a lot of other disease conditions (Singh et al. 2011). However, some mild and brief-type adverse events such as epigastric discomfort and loose stools were reported as most common, whereas drowsiness, hallucinogenic, nasal congestion (rhinitis), cough, cold, decreased appetite, nausea, constipation, dry mouth, hyperactivity, nocturnal cramps, blurring of vision, hyperacidity, skin rashes, and weight gain were reported as less common adverse side effects (Tandon and Yadav 2020).

Table 1.

Ethnomedicinal usages of W. somnifera

| Ethnomedicinal usage | Plant part | Geographical location | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | Young shoots | South Africa, India | Duke et al. (1985) |

| Eye treatments | Leaf | Kenya | Duke et al. (1985) |

| Abortifacients | Leaf, root | Morocco (used with other plants), South Africa | Merzouki et al. (2000), Moroole et al. (2019) |

| Sedatives | Root | South Africa | Elizabeth and Dabur (2002), Umadevi et al. (2012) |

| Aphrodisiac | Flower and dried mature roots | Tanzania, India | James (2002), Chauhan et al. (2014) |

| Kidneys, Fever | Leaf, root | South Africa | Van et al. (2008) |

| Skin infection (Smallpox, Measles, etc.) | Leaf, stem, and berry | South Africa, Jordan | Al-Qura'n (2009), Mabona and Van (2013) |

| Ethnoveterinary (Anthrax) | Dried roots | Ethiopia | Eshetu et al. (2015) |

| Gynaecological | Leaf, fruit, root | Lesotho, Pakistan | Moteetee and Seleteng (2016), Aziz et al. (2018b) |

| Haemorrhoids | Green fruit | Iran | Hashempur et al. (2017) |

| Pulmonary troubles | Leaf, root | Pakistan | Alamgeer et al. (2018) |

| Asthma and Malaria | Leaf-sap | Pakistan | Umair et al. (2019) |

The raises in W. somnifera market demands in Africa and elsewhere mostly associate with its extensive medicinal, nutritional, and cosmetic applications. In particular, its uses in the productions of pharmaceutical drugs and products for human consumption, including energy drinks, capsules, health supplements, energy boosters, and food product materials, have been remarkably notable (Jayanta et al. 2018). Sales in these forms are flourishing worldwide due to its reputation as a natural solution to health, beauty, and nutrition-related problems. The vast majority of W. somnifera in the market is supplied to herbal products and dietary supplement manufacturers in the form of dry extract, with a global market value worth over $12 million (Vineet et al. 2018). In Africa, the sale of W. somnifera is exercised in open markets as well as in herbal shops. For example, in the Eastern Cape Province, herbal cosmetic products are more frequently bought from herbal shops, but in a few cases, they are also still prepared at home, especially those used for skincare management (Idowu and Wilfred 2018). The major companies involved in the W. somnifera extract market include Life Extension, Taos Herb Company, General Nutrition Centers, Jarrow Formulas, Hugh Mountains, Organic India, and Vitamin Shoppe. The main market types include capsule and liquid, while the main applications include herbal products and drugs (Jon 2017). The USA is the largest W. somnifera market, with over 40% of products sold at the end of 2017 contained this plant. These products mainly included dietary supplements, sports nutrition products, and functional food (beverages, bars, and snacks). The main reason for the broad market of the plant in the USA is likely due to its constituent’s antistress, antifatigue, and anti-insomnia properties, among others. Other countries with profitable markets include the UK, India, and Germany (Jon 2017).

Review methodology

This review focuses on recent studies that underscore the W. somnifera degrees of use, highlighting its ethnography, ethnomedicinal usage, phytochemistry, and toxicological effects. The potential pharmacological efficacy of W. somnifera against several pathophysiological conditions is herein thoroughly discussed. Additionally, the significance of commercializing the plant in Africa for drug development is also extensively reviewed to provide the much-needed highlights towards its benefit to Africa. Scientific articles and publications were scooped and sourced from high-impact factor journals and filtered with relevant keywords on W. somnifera. Several scientific databases, including GBIF, PubMed, NCBI, Google Scholar, Research Gate, Science Direct, SciFinder, and Web of Science, were accessed for surveying the most influential articles and recent breakthroughs published in the context of W. somnifera.

Ethnography and ethnomedicinal usage of W. somnifera

Ethnography of W. somnifera

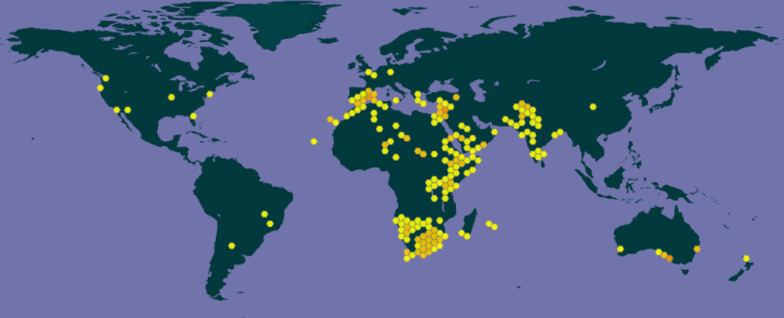

W. somnifera is commonly known as Tarkukai in the Marakwet community of Kenya, Karamanta in the northern part of Nigeria, Zafua in Mali, and Winter Cherry in South Africa (Burkill 1985). The distribution area of W. somnifera extends from the Canary Islands and the Mediterranean region through Africa, the Middle East, India, and Sri Lanka to China (Schmelzer et al. 2008). It possesses a natural occurrence, most abundantly in dry and humid regions (Gaurav et al. 2015). In Africa, W. somnifera is present in the northern-, southern-, and eastern-region countries and few countries in the western-region (Gaurav et al. 2015). In the north African countries, W. somnifera is common in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Sudan but absent in Western Sahara. The plant is present in all countries in the southern part of the African continent. Its presence has also been recorded in Chad, Cape Verde, Mali, Liberia, and Nigeria in the western part of Africa. In the eastern part of the continent, countries including Ethiopia, Tanzania, Angola, Zambia, Mozambique, and Eritrea have this plant growing there (Fig. 1) (Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal in GBIF Secretariat 2021).

Fig. 1.

Ethnographic distribution of W. somnifera (Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal in GBIF Secretariat 2021)

Ethnomedicinal usage of W. somnifera

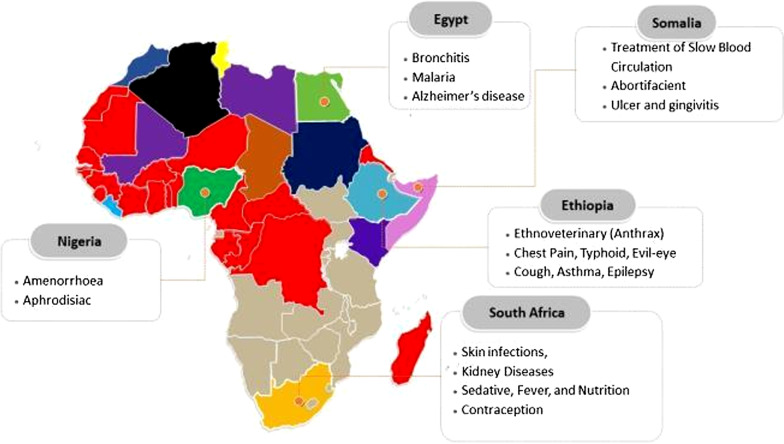

Extensive usage of W. somnifera in Africa for medicinal purposes (Fig. 2) has been documented in literature (Burkill 1985; Schmelzer et al. 2008; Moroole et al. 2019). Among the 23 species present in the Withania genus, W. somnifera is economically more valuable because of its medicinal properties (Kulkarni and Dhir 2008; Mirjalili et al. 2009). In Cape Verde, locals commonly use an infusion of the W. somnifera leaves for blood purification and the whole plant as a diuretic and antibacterial, such as against gonorrhoea (Schmelzer et al. 2008). Notably, the people of Ethiopia are extensively reported to frequently make use of W. somnifera to treat cough, asthma, epilepsy, eye infections, scabies, and paralysis, as well as evil eyes and evil spirit (Giday et al. 2003; Wondimu et al. 2007; Teklay et al. 2013). Moreover, the Zay people of Ethiopia are exclusively documented to also employ W. somnifera in the treatments of chest pain and typhoid (Giday et al. 2003).

Fig. 2.

Ethnomedicinal usage distribution of W. somnifera in African countries and the plant applications in selected countries

The smoke of a burning W. somnifera is wafted over patients with slow blood circulation in Somalia (Raut et al. 2012). In Sindhi, the leaves or roots are pounded together with the parts of other plants and administered as an abortifacient (Saiyed et al. 2016). The W. somnifera leaves are purgative, and therefore, its crushed forms are used as a general body pain reliever, including in the treatment of chronic skin ulcers (Kipkore et al. 2014). W. somnifera is employed for contraception and other reproductive problems in the Eastern Cape, Free State, and Kwazulu-Natal of South Africa (Moroole et al. 2019). There is reported usage of W. somnifera in combination with leaves of Ensete vetricosum, whereby both are boiled together to treat candida infection in Venda, South Africa (Masevhe et al. 2015). Also, the leaves of W. somnifera are used in wound healing by applying on open wound abscesses by the people of the Eastern Cape of South Africa (Grierson and Afolayan 1999). In the Lagos state of Nigeria, people commonly use W. somnifera for amenorrhoea and aphrodisiac purposes (Sharaibi et al. 2017). Given the vast ethnomedicinal usage, the findings of numerous recent studies in clinical and experimental settings further reveal the efficacy of W. somnifera for the management of several pathological conditions and provide added substantial highlights on its medicinal significance (Priyanka et al. 2020; Fuladi et al. 2021).

Phytochemistry and toxicological studies of W. somnifera

Phytochemistry of W. somnifera

Through the application of various chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques, the phytochemical constituents of W. somnifera root, leaves, stem, and fruit extract have been extensively explored and characterized (Mirjalili et al. 2009). These phytochemical investigations on different parts of W. somnifera plant extracts indicate the presence of several biochemically active components, including alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, carbohydrates, steroidal lactones, β-sitosterol, scopoletin, sitoindosides, somniferiene, somniferinine, pseudotropine, anaferine, anahygrine, cysteine, chlorogenic acid, cuscohygrine, withanine, withanolides, withananine, tropanol, 6,7β-Epoxywithanon and 14-α-hydroxywithanone (Naz and Choudhary 2003; Saleem et al. 2020). Noteworthy, these extract constituents are held responsible for the various biological activities of effect in the plant ethnomedicinal usage and pharmacological efficacy (Aye et al. 2019; Nile et al. 2019). Specifically, the W. somnifera whole plant and its different parts phytochemical extracts composition outline as indicated below: -

1. The W. somnifera whole plant extract is rich in phytochemicals, such as alcoholic extract of the plant contains anaferine, anahygrine, choline, cuscohygrine, pseudotropine, dl-isopelletierine, and tropine (Saleem et al. 2020). Besides, the methanolic extracts of the plant constitute starch, acylsteryl glucosides, iron, ducitol, hantreacotane, withaniol, and amino acids such as alanine, aspartic acid, cysteine, tyrosine, glutamic acid, glycine, proline, and tryptophan (Mirjalili et al. 2009; Alam et al. 2011). The aqueous extract of the whole plant contains withanone and tubacapsenolide F (Saleem et al. 2020), while similar extracts with equimolar ratios of water and methanol constitute chlorinated withanolide and 6α-chloro-5β,17α-dihydroxywithaferin A along with nine withanolides, namely 6α-chloro-5β-hydroxywithaferin A, (22R)-5β-formyl-6β,27-dihydroxy-1-oxo-4-norwith-24-enolide, 2,3-dihydrowithaferin A, withanone, withanoside IV, withaferin A, 2,3-didehydrosomnifericin, 3-methoxy-2,3-dihydrowithaferin A, and withanoside X (Saleem et al. 2020). The ethanol extract of the whole plant constitutes isosominolide, sominone, withasomniferin A (Misra et al. 2008).

2. Extract of W. somnifera root using alcohol extractant yields a pyrazole alkaloid, withanolide A, and withasomnine (Baek et al. 2019). Methanolic extract of the plant root constitutes withanosides I-VII (Menssen and Stapel 1973; Mirjalili et al. 2009), whereas three withanolides, namely withanolide A, B, and C, make the benzene and ethyl acetate extracts of similar roots (Kim et al. 2019). β-sitosterol and d-glycoside are the major phytochemical components of the plant’s root extraction with petroleum ether and acetone (Saleem et al. 2020). Butanol extracts of W. somnifera roots display the phytochemical existence of physagulin, withanoside IV, and withanoside VI (Mathur et al. 2006; Chatterjee et al. 2010).

3. Leaves of the plant extracted with methanol show the phytochemical presence of ashwagandhine, cuscohygrine, dl-isopelletierine, somniferine, tisopelletierine, 3α-tigloyloxtropine, 3-tropyltigloate, hygrine, hentriacontane, mesoanaferine, visamine, withanine, withananine, withasomnine, and pseudowithanine (Siddique et al. 2014). Alcoholic extract of the plant leaves constitutes withanolide D, E (Lavie et al. 1968, 1972), withanolides F–M (Glotter et al. 1973, 1977), withanolides N, O (Ganzera et al. 2003), and withanolide P (Glotter et al. 1977). Leaves of the plant extracted with ethanol contain (5R,6S,7S,8S,9S,10R,13S,14S,17S,20R,22R)-6,7α-epoxy-5,17-α,27-trihydroxy-1-oxo-22R-witha-2,24-dienolide (Ben et al. 2018). Methanolic extract of the plant roots constitutes numerous dragendorff positive alkaloids that are phytochemicals recognized as anaferine, anahygrine, choline, pseudotropine, cuscohygrine, isopelletierine, dl-isopelletierine-3-tropyltigloate, hentriacontane, hygrine, mesoanaferine, somniferine, 3α-tigloyloxtropine, visamine, withanine, withananine, and withasomnine along with ashwagandhine, pyrazole derivatives, and pseudowithanine (Saleem et al. 2020).

4. Ethanolic extract of the W. somnifera stem bark mainly contains withanolides, including somniferanolide, somniwithanolide, somniferawithanolide, withasomnilide, and withasomniferanolide (Siriwardane et al. 2013; Saleem et al. 2020).

5. Oil extracts from fresh berries of W. somnifera contain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids such as elaidic acid, linoleic acid, oleic acid, palmitic acid, and tetracosanoic acid (Sidhu et al. 2011). Methanolic extract of the plant fruits possesses withanamides A-I (Bhatia et al. 2013) and 6,7α-epoxy-1α,3β,5α-trihydroxy-witha-24-enolide (Adhikari et al. 2020).

Toxicological studies of W. somnifera

Studies have revealed the safety profile of several extracts of W. somnifera for all age groups and sexes, even during pregnancy (Raut et al. 2012; Patel et al. 2016). Administration of 2000 mg/kg of body weight of the hydroalcoholic extract for acute and sub-acute oral toxicities in albino rats of Wistar strain is determined to be practically safe (Patel et al. 2016). Other reported studies also indicate that 1260 mg/kg of bodyweight mark the mean lethal dose (LD50) of this plant extract in Swiss albino mice, and any increase above this dose limit is proven to lead to the death of the treated mice (Sharada et al. 2008; Dar et al. 2015). In a similar study, the administration of W. somnifera extract in Wistar rats showed no toxicologically significant treatment-related changes in biochemical observations, ophthalmic examination, bodyweight changes, feed consumption, as well as organ weight, even at 2000 mg/kg of bodyweight high dose (Prabu et al. 2013).

Evaluations of dose-related tolerability, safety, and activity of W. somnifera formulation (aqueous extract in capsules ranging from 750 to 1250 mg/day) in normal individuals are experimented with (Raut et al. 2012). Finding on the formulation are reported safe and shown to strengthen muscle activity. A sub-acute toxicity study involving a combination of W. somnifera and Panax ginseng also revealed no significant toxic effect on studied parameters (Aphale et al. 1998), hence, substantiating the claim of W. somnifera safety for consumption. A recent survey of studies that involved several preclinical scientific studies and clinical trials on the toxicity of W. somnifera establishes evidence on its extracts (aqueous, ethanolic, or hydroalcoholic) reasonable safety for herbal medicine use (Tandon and Yadav 2020).

Potential pharmacological efficacy of W. somnifera against pathophysiological conditions

Cardiovascular diseases

W. somnifera is widely used as a therapeutic drug in Ayurveda and Unani medicines (Palliyaguru et al. 2016). This plant is known to grow in Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean region and has been extensively used in African Traditional Medicine (ATM) for managing different pathological conditions, including cardiovascular diseases (Dar et al. 2015; Chukwuma et al. 2019).

Cardiac-related infarction is one of the major leading causes of death globally (Siegel et al. 2016). Interestingly, the findings of reported studies indicate the W. somnifera therapeutic significance in ameliorating myocardial infarction (Bilal et al. 2012). The antioxidant activity and the antiapoptotic properties of the W. somnifera extracts are confirmed to have a significant cardioprotection effect based on the myocardial and antioxidant histopathological evaluations (Mohanty et al. 2004, 2008). Another study reported on the W. somnifera extracts potential cardio-tonic and cardioprotective effects in preventing myocardial infarction and ischaemia–reperfusion injury to the heart also proven the therapeutic value of the herb extracts in the cardiovascular context (Raghavan and Shah 2015). Further, an in vivo study on the biochemical and histopathological parameters showed that the extract of W. somnifera protects the myocardial cell membrane due to its antilipoperoxidation and antioxidants effects (Khalil et al. 2015). The acute toxicity of the W. somnifera extract at 2000 mg/kg is determined practically safe, and its administration presents low toxicity (Prabu et al. 2013; Patel et al. 2016), however significant to combat many pathophysiological diseases.

Reported studies indicate that root extracts of W. somnifera enhance cardiorespiratory endurance and improve the quality of life among healthy athletic adults, while suggesting a careful selection of doses to prevent heart failures (Sandhu et al. 2010; Choudhary et al. 2015; Perez-Gomez et al. 2020). An Auto-Dock-Vina model on different proteins associated with cardiovascular diseases enlightens that Withaferin A is a potential lead compound that can inhibit cardiovascular diseases (Ravindran et al. 2015).

Furthermore, reported study findings suggests that Withaferin A inhibits apoptosis via activated oxidative stress demonstrating mechanisms of action in the H2O2-induced oxidative stress injury model through improved cell survival and reduced oxidative stress, which all insight to this W. somnifera bioactive constituent utilization as a drug candidate for the treatment of cardio-related diseases (Yan et al. 2018b). The root powder of W. somnifera at 50 mg/kg of body weight (BW) and 100 mg/kg BW significantly reduces right-ventricular pressure and other parameters on mono-crotaline induced pH in rats by remarkably improving in inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, attenuation of proliferative markers, and apoptotic resistance in lungs (Kaur et al. 2015).

Interestingly, findings of a research study on the therapeutic efficacy of the root powder of W. somnifera for the management of hypertension suggest that the intake of the root powder with milk decreases systolic blood pressure (Kushwaha et al. 2012). Further, in a meta-analysis review on the active chemical compounds of W. somnifera, Withaferin A is underlined to have therapeutic potential against COVID-19 pandemic infection-induced cardiorespiratory disease (Straughn and Kakar 2020). The study suggests that the Withaferin A steroidal lactone ring could mitigate the virus-induced cardiovascular pathological features (Afewerky 2020) through the mechanisms that include anti-inflammatory actions and even binding to the viral spike (S-) protein of SARS-CoV-2.

Neurodegenerative diseases

Mainly over the last couple of decades, with the increasing life expectancy, the incidence and prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases have increased substantially (Lopez and Kuller 2019). Therefore, the public health impact of neurodegenerative diseases in the ageing baby boom generation requires priority attention. To address this concern, several preliminary research, preclinical studies, and clinical trials have been undergoing. However, because of the disease’s pathophysiological complexity, there is no efficient pharmaceutical approach for the prevention or treatment of neurodegenerative diseases at the moment.

While further research is required, the ongoing pharmaceutical investigation efforts for the therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases signify the potential role of medicinal plants, such as W. somnifera, extracts than the use of synthetic approaches in terms of both treatment efficacy and access (Pohl and Kong 2018). W. somnifera has a long history as a medicinal plant to treat various neurodegenerative conditions (VenMurthy et al. 2010). Neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by a slow and progressive deterioration of the central nervous system structure and function (Dugger and Dickson 2017). Mainly over the last decade, W. somnifera has gained extra attention in the context of treatment for neurodegenerative ailments, including loss of memory (Uddin et al. 2019), bipolar disorder (Chengappa et al. 2013), and locomotor defects (Manjunath and Muralidhara 2015). Interestingly, the most reported neuroprotective mechanisms of W. somnifera extracts against several neurodegenerative diseases include the restoration of mitochondrial function concurrent with the mitigations of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis (Dar et al. 2017; Birla et al. 2019; Gupta and Kaur 2019).

Role of W. somnifera against Alzheimer’s diseases

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of neurodegenerative disease that causes progressive impairment of higher cognitive function, memory, and social skills (SoriaLopez et al. 2019). The pathogenesis of AD is not yet fully elucidated. However, age is considered as the AD primary risk factor, and the aggregation of extracellular Amyloid-beta (Aβ) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are referenced as the disease’s major pathological hallmarks (Chen et al. 2019). Several research studies on the neuropathogenesis mechanism of AD insight neuronal calcium dyshomeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis as the principal contributing factors to the disease pathology and pathophysiology (Afewerky et al. 2016, 2019; Yan et al. 2018a; Mahaman et al. 2019). Notably, the root extract of W. somnifera has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the level of Aβ-induced reactive oxygen species in N-SH neuron-like cells (Singh and Ramassamy 2017) and reverse cognitive impairments by ameliorating dendritic, axonal, and synaptic integrity in animal models of AD (Uddin et al. 2019). Furthermore, the W. somnifera root extracts have shown promising results in the aspects of cognitive and memory improvement in several preclinical studies of AD, including a pilot study in adults with mild-cognitive degeneration (Choudhary et al. 2017a). The protective mechanisms of W. somnifera root extract against AD pathology presumably involve binding of the extract–biochemically active constituents to the active motif of Aβ, thereby preclude Aβ fibril formation. However, multidisciplinary extensive preliminary research is needed before disseminating the plant extracts for the AD pharmacological approach.

Role of W. somnifera against Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent progressive neurodegenerative disease of ageing after AD, known for causing locomotor deficits (Marino et al. 2020). The main pathological hallmarks of PD include pronounced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain substantia nigra and aggregation of neuronal Lewy Bodies (Marino et al. 2020). Research studies suggest that environmental toxins, such as certain pesticides, that induce mitochondrial dysfunction are the major contributing factors of PD (Wirdefeldt et al. 2011; Bragoszewski et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017). However, the PD pathogenesis mechanisms remain unclear, and there is no definitive PD-modifying therapy to date. Remarkably, W. somnifera extracts have been documented to reverse PD-pathology, including levels of dopamine in the striatum (Manjunath and Muralidhara 2013), and improve locomotor defects in the Drosophila melanogaster model of PD (Manjunath and Muralidhara 2015). Further, reported studies in several PD models indicated that W. somnifera extracts significantly reverses the Parkinsonian phenotype (Surathi et al. 2016). Although further studies are required to determine the protective mechanisms of W. somnifera extract against PD, this plant active constituent’s distinct antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties likely attribute to correcting mitochondrial aberration and dopamine levels in the striatum.

Role of W. somnifera against Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder that causes a progressive loss of locomotor coordination and cognition (Jimenez-Sanchez et al. 2017). An inherited huntingtin gene in chromosome 4 is known to induce nerve cells damage in the HD brain (Nance 2017) through mechanisms that are not well understood. Notably, the root extract of W. somnifera has been revealed to ameliorate biochemical parameters, including antioxidant enzymes, responsible for protecting huntingtin protein-induced lesions in basal ganglia tissue and the behavioural outcomes of HD animal models (Kumar and Kumar 2009). Additionally, reported studies of W. somnifera extracts pharmacological effect suggest potential roles of the extracts to decrease the lipid-peroxidation and choreiform movements in an animal model of HD (Dar et al. 2015). The GABAergic and antioxidant regulation capability of W. somnifera root extract make the plant root extracts suitable neuroprotective candidates against HD; however, research studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms.

Reproductive impotence

Infertility is regarded as the inability to become pregnant upon regular unprotected intercourse for a year. Infertility could be caused by several factors such as the male factors, a disorder in ovulation, abnormalities in uterine, tubular obstruction, peritoneal factors, or cervical factors, which ultimately emanate from previous reproductive tract infection and complications, exposure to a toxin, among several other factors (Lindsay and Vitrikas 2015). Sexual dysfunction and infertility happen to be critical health concerns worldwide (World Health Organization 2007). The absence of gonadotropin, a hormone in the functions of men and women’s reproductive system stimulated from the pituitary gland, also known as Follicle-Stimulating-Hormone, affects the normal quantitative and qualitative spermatogenesis even in animals (Sharma et al. 2015). Notably, several injectable medications, including gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), recombinant follicle-stimulating hormones, and human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) and the oral medications, such as clomiphene citrate, which are administered for improving abnormal semen, stimulating gonadotropin, and ultimately enhancing spermatogenesis are associated with many shortcomings ranging from high cost to toxicity and various side effects (Buchter et al. 1998). In addressing these reproduction problems, phytomedicine has played a significant role, and a considerable number of natural products have been reported to be efficacious, with positive outcomes (Bussmann and Sharon 2006; Bussmann and Glenn 2010). Besides, properties such as low cost, availability with little to no side effects have given plant resources preference over existing conventional medicine. One plant species that has attracted attention as an aphrodisiac or potent remedy for reproduction impotence is W. somnifera (Weiner and Weiner 1994). It contains withanolides—the principal bioactive function of the plant (Walvekar et al. 2013; Nasimi et al. 2018b) and is present in herbal formulations marketed in many countries, especially in Asia (Adhikari et al. 2018). Previous studies reported that W. somnifera enhances steroidal hormones and improves sexual distress in both males (Ilayperuma et al. 2002; Kiasalari et al. 2009; Nejatbakhsh et al. 2016; Durg et al. 2018) and females (Dongre et al. 2015). Extracts of W. somnifera mildly stimulates the release of gonadotropin hormones in adult rats (Kataria et al. 2015; Rahmati et al. 2016) and improves human menopausal syndrome (Mali et al. 2015). Excessive free radicals, the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, are generated when the antioxidants level is comparatively low in a body system and produced from the subcellular compartment of testes lead to cell damage and ultimately oxidative stress. Oxidative stress that attacks the fluidity of the sperm plasma membrane and DNA integrity in the sperm nucleus (Agarwal et al. 2003) has been reported to be inhibited by W. somnifera (Kulkarni and Dhir 2008; Walvekar et al. 2013) owing to its antioxidant properties. Several studies have validated the aphrodisiac, spermatogenic, and fertility effect of the root, leaf, stem, and fruit extracts of W. somnifera both in humans not only in the open literature (Bussmann and Sharon 2006; Mahdi et al. 2009; Ahmad et al. 2010; Tandon and Yadav 2020) but also as patents (Majeed et al. 2019; Gokaraju et al. 2020) and in animals (Abdel-Magied et al. 2001; Kaspate et al. 2015).

W. somnifera extracts could be used for the treatment of oligospermia (Dongre et al. 2015) and enhancing libido (Kyathanahalli and Manjunath 2014). In humans, clinical investigations on the efficacy of W. somnifera have been reported (Ahmad et al. 2010; Gupta et al. 2013; Dongre et al. 2015; Khalil et al. 2015), including a pilot study on the clinical investigation of the spermatogenic activity of standardized capsule of W. somnifera root extract on 46 male patients with oligospermia (< 20 million/mL) focusing on estimating their semen parameters and serum hormone levels after a 12-week treatment. In the study, 225 mg full-spectrum capsule of W. somnifera root extract was administered orally-3-times daily for 90 days to 21 patients and compared with 25 patients on placebo. The results demonstrated that the sperm count, semen volume and sperm motility increased by 167% (9.59 ± 4.37 × 106/mL to 25.61 ± 8.6 × 106/mL), 53% (1.74 ± 0.58 mL to 2.76 ± 0.60 mL) and 57% (18.62 ± 6.11% to 29.19 ± 6.31%), respectively, at P < 0.0001 on the 90th day. Similarly, a very recent triple-blind randomized clinical study compared the effects of W. somnifera with pentoxifylline on sperm parameters of 100 idiopathic infertile male patients for 90 days (Nasimi et al. 2018a). The result demonstrated that W. somnifera root extract improved sperm parameters without any adverse effect. The mechanism of action of W. somnifera on male infertility patients is by suppressing oxidative stress (Tahvilzadeh et al. 2016).

A study in an animal (Kaspate et al. 2015) investigated the aphrodisiac activity of an authenticated hydroalcoholic extract of dried W. somnifera root in tubal ligated female Wistar rat. Different concentrations (100, 200, and 300 mg/kg/day) were gavage administered for 21 days with the reading of the sexual behaviour taken on the 11th and 21st days. The results demonstrated that sexual motivation, hormonal level, and histology of the genital organ of the rats increased at doses of 100, 200, and 300 mg/kg/day when compared with the estrous control. W. somnifera has been reported to possess a phytoremedial effect as an antidote against arsenic-induced reproductive toxicity (Sharma et al. 2015). It is also evident as a potent enhancer of sexual function and behaviour by increasing testosterone levels and regulation of NF-κB and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways in male rats (Sahin et al. 2016). However, there exists some variance in the reproductive potency effects of W. somnifera. For instance, it was reported to possess spermicidal activity (Nasimi et al. 2018b), decrease sex accessory organs in adult male albino rats (Mali et al. 2015), and have no relief improvement in psychogenic erectile dysfunction when compared with placebo (Mamidi and Thakar 2011). Although Azgomi et al. (2018) surmised that such variations could be as a result of the interventions or protocols adopted in the trials. It is, therefore, crucial and beneficial that adequate clinical evidence is reached on W. somnifera either in humans or animals using standard doses before its integration as medicine for the treatment of sexual dysfunction issues.

Other chronic diseases

Anticancer potentials of W. somnifera

Various in vitro and in vivo studies have proven the potential efficacy of W. somnifera in the prevention and treatment of different types of cancers as a result of its rich pool of pharmacologically relevant secondary metabolites and chemical constituents. Scientific findings have evidenced that two chemical components of W. somnifera, namely withanone and withaferin A, could be employed in the development of cancer drugs (Vaishnavi et al. 2012). Further, several studies have pointed out some well-defined mechanisms through which W. somnifera exhibits anticancer activities, including regulation of DNA damage pathway, induction of oxidative stress, nuclear factor (NFk-b), signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) signalling, PI3K (phosphoinositide-3-kinase)/AKT (a serine-threonine protein kinase), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling, and inhibition of angiogenesis (Widodo et al. 2008). Mayola et al. (2011) showed the anticancer effect of withaferin A on melanoma cells through the induction of oxidative stress mechanisms (Mayola et al. 2011). A report by Yang et al. shows that withaferin A in combination with radiation stimulated apoptosis by the generation of reactive oxygen species and several other mechanisms, including the stimulation of MAPK signalling, Bcl-2 downregulation, and caspase-3 activation (Yang et al. 2011). Hahm et al. (2014) showed that cytotoxicity induced by withaferin A is cell line-specific and much dependent on the MAPK signalling pathway (Hahm et al. 2014). Withaferin A has also given a positive result against the formation of the mammosphere in human breast cancer through apoptosis and complex III mitigation (Lee et al. 2012). Withaferin A has also proved efficacious against experimental mammary tumours by inhibiting the expression of vimentin (Lee et al. 2016) and interfering with the cytoskeletal architecture of β-tubulin (Antony et al. 2014). Withaferin A also decreased the tumour size of mammary gland carcinoma in a transgenic mouse (Kim and Singh 2014; Kim et al. 2020). Withaferin A proved positive results in a kidney cancer cell line by eliciting numerous apoptotic pathways and cleavage of Poly (Adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) through the inhibition of the STAT3 pathway (Um et al. 2012). Several other studies have recorded the anticancer effects of W. somnifera (Setty et al. 2017; Dar et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020; Maheswari et al. 2020; Saggam et al. 2020).

Effect of W. somnifera on stress and stress-related obesity

Stress, a normal body reaction, increases concentrations of cortisol in blood that subsequently can lead to several other cascades of events. Interestingly, the architecture of the human body is naturally designed to experience stress and react to it. Stress can be regarded as positive or negative. Many well-documented studies have shown that W. somnifera is a notable stress reliever and consequently able to help in weight loss. Particularly studies on root extract of W. somnifera have shown significant effect as a potential candidate for lowering stress and stress-induced eating that may, consequently, lead to weight loss. There is linkage pointing to stress as an essential factor in obesity due to its direct effect on eating habits and the rate of metabolism in such a manner that may contribute to weight gain. Researchers have thought that any drug or medicinal plant extract or combination with the potential ability to reduce stress could be a promising candidate for individuals who are susceptible to stress-induced obesity. In line with these existing assumptions on stress as a contributing factor in obesity, W. somnifera is one medicinal plant noteworthy for its potentials to significantly reducing some symptoms of anxiety (Pratte et al. 2014). In a recent study conducted by Choudhary et al., obese people with high-stress index fed with 300 mg of root extract of W. somnifera two times daily for 8-consecutive weeks showed a significant improvement in some measure indices, including body weight, levels of the stress-related hormones, and reduction in stress-induced eating and feeling (Choudhary et al. 2017b). This result suggests that the root extract of W. somnifera can be employed for the management of stress-induced obesity in individuals. Other researchers also reported similar results for the anxiolytic effect of W. somnifera (Chandrasekhar et al. 2012; Candelario et al. 2015; Manchanda and Kaur 2017; Lopresti et al. 2019; Salve et al. 2019; Deshpande et al. 2020).

W. somnifera as an antimicrobial agent

In folkloric medicine, W. somnifera has proven efficacious against infections. The antimicrobial activity of W. somnifera depends on the organism involved, and this is achieved through several mechanisms, including but not limited to cytotoxicity, immunopotentiation, and gene splicing. To scientifically validate the use of W. somnifera in traditional medicine several research studies have reported effective-antifungal and antibacterial effects of the plant extracts in a laboratory setup, including a favourable zone of inhibitory effects on gram-positive Enterococcus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus (Bisht and Rawat 2014). A similar finding was recorded on the effect of W. somnifera against gram-negative bacteria (Singh and Kumar 2011; Alam et al. 2012).

Commercialization of W. somnifera in Africa

W. somnifera is a plant widely known for its nutritive value and medicinal uses. It is commonly found and cultivated in India (Durg et al. 2018). Although it does not have a uniform distribution across Africa, it is prevailing in countries including South Africa, Lesotho, Botswana, Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), Namibia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Djibouti, Egypt, Tanzania, Swaziland, Mali, Nigeria, Liberia, and Congo (Burkill 1985; Dzoyem et al. 2013; Gaurav et al. 2015). However, it is usually not found in all provinces of these countries (Gaurav et al. 2015).

W. somnifera is majorly seen as a weed in several places, as it usually grows on its own without prior planting. However, it grows and survives best in areas of less rainfall or water, preferably dry and warm heated areas; and as a result, it rarely exists in all regions (Gaurav et al. 2015). This primary growth factor of W. somnifera suggests that the drier parts of Africa can give more attention to its deliberate cultivation (Shanmugaratnam et al. 2013). Several studies are available on the cultivation and management of W. somnifera (Rajeswara et al. 2012; Shrivastava and Sahu 2013) that enlightens as references for an actionable investment project on the herb and its extracts.

Traditionally, every part of W. somnifera has been used in various forms to treat different diseases and ailments like cough, skin infections, malaria, fever, dysentery, asthma, stress, ulcer, infertility, insomnia, etc. (Verma and Kumar 2011; Umadevi et al. 2012; Nasimi et al. 2018b). Due to the enormous nutritional value and medicinal uses of W. somnifera, there exists an immense market demand for this plant. Notably, the high demand for this plant and its extracts has led to a rise in its cultivation and production globally, which in turn signifies its commercialization significances both in the local and international markets. Over 7000 tons of W. somnifera root production is needed yearly, and India, the largest source of the plant product, produces only about 1500 tons each year (Umadevi et al. 2012). Unfortunately, there are limited articles and publications available on W. somnifera commercialization in Africa.

Africa is indigenous to many medicinal plants and natural products. However, there is poor documentation of medicinal plants in Africa, including W. somnifera. There is, therefore, a need for a comprehensive compilation of and research on plants used in traditional medicine in different regions of Africa. As much as it is known, at the time of writing this literature review, only very few studies have reported on the occurrence of W. somnifera in Africa. For instance, the W. somnifera occurrences in Congo, Egypt, and Morocco have been documented (Jana and Charan 2018), but there is no substantial information on the plant ethnomedicinal usage and commercialization features in these areas.

Africa is yet to fully tap into the commercialization of W. somnifera on a global scale. As of the time of this report, there are little or no reference details accessible on the commercialization of this medicinal plant in Africa. Although this plant is abundantly present in Africa, it is recognized only for its usage and demand in a local context. Undeniably local markets are beneficial to start with for basic economic sustenance in communities of interest. However, Africa needs to consider international commercialization because local level markets are typically crude, informal, and unregulated, while the practices concerning traditions and customs in worldwide settings benefit most the entire population. At the moment, most African plant materials are gotten through wild harvesting and wild crafting (VanWyk 2015). The rise in demand and pressure for medicinal plant materials place urgent considerations for deliberate cultivation and management of plants rather than wild harvesting. Noteworthy, the sustainability of W. somnifera in its natural flora is crucial as wild harvesting of plant materials can pose a threat to the human race as the plant might not be able to resist pressure from humans and thereby extinct (Street and Prinsloo 2013). Thus, there is a call for large-scale cultivation, production, and commercialization of W. somnifera in Africa as this will enhance the growing economy while also reducing the current high rate of unemployment in most African countries. In addition to the economic benefit, the international commercialization of W. somnifera in Africa would also promote mutual relationships in several global aspects between Africa and the world. Africa lags other continents of the world when it comes to the commercialization of medicinal plants. The W. somnifera large-scale cultivation and commercialization are vital to initiate with aiming for subsequent promotions of the other related medicinal plants of significance due to the proven recent rises in W. somnifera products demand in international pharmacological industries alongside the local people needs.

The acceptance and demand of W. somnifera in traditional medicine are evidenced in the high number of citations and publications over time. Less than 2% of the medicinal plants predominantly common in South Africa have been made accessible as refined substances in various forms like drugs, dietary supplements, balm, or pills (VanWyk 2008). Ethiopia is one of the other African countries that takes part in the commercialization of W. somnifera at the rate of 3.03 USD per kg (Dzoyem et al. 2013); however, there is limited data on the plant use within Ethiopia or which of the plant parts is at most used traditionally. Unlike developed countries, the lack of commercialization of medicinal plants in African countries can be partly traced to a lack of reliable data and market secrecy (Dzoyem et al. 2013). The world’s interest in W. somnifera has placed pressure on its demand and thus creates an opportunity for large-scale cultivation for commercialization. For instance, there is a yearly increase in the market demand of W. somnifera in India wherein above 4000 hectares of land is exclusively used for this plant cultivation in Madhya Pradesh, a drier Indian state (Shrivastava and Sahu 2013).

It is germane to note that although W. somnifera is distinctly recognized among the African indigenous plants with the highest number of research publications of about 1767 papers, there exist not much data on the plant commercialization by the African community (VanWyk 2015). Even with the vast commercialization of W. somnifera going on in other parts of the world, wherein this plant is available in various forms and combinations in the market, such as a paste, powder, pellets, capsules, medicinal raw materials, drugs, supplements, or extracts; except that of South Africa, reference data covering this plant commercialization in the Africa continent remains unavailable.

Conclusions

The acceptance and demand of W. somnifera in traditional medicine to prevent or treat several pathophysiological conditions, including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and reproductive impotence, place higher demands for the plant’s deliberate large-scale cultivation, production, and international commercialization in Africa. The commercialization of W. somnifera will be beneficial to Africa in several ways, including: -

Awareness—the sales of this plant will create more awareness about the potential of the region. This will attract international partners, thereby strengthening international relations.

Financial and economic independence—the sales of this plant will strengthen the financial power of the involved people and boost their economic independence-alleviating poverty in the region.

Reduction of the unemployment rate—commercialization will involve aspects like advertising, marking, and logistics. This will lead to the recruitment of personnel, thereby reducing the unemployment rate.

Acknowledgements

The Organization of African Academic Doctors (OAAD) connected the authors for research collaborations to work as a team. This work was conducted independently of the OAAD and does not necessarily reflect the organization’s opinions.

Abbreviations

- GBIF

Global biodiversity information facility

- LD50

Mean lethal dose

- BW

Body weight

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PARP

Poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase

Authors' contributions

HKA and AEA conceived and initiated the review process. SBA and BBT performed a majority of writing on ethnography and ethnomedicinal usage sections. HKA, AEA, JIO, and ESO performed a majority of writing on phytochemistry, ethnomedicinal usage, and pharmacological efficacy sections. AOO and PNNB performed a majority of writing on ethnography and commercialization sections. HKA undertook the compilation and typesetting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Henok Kessete Afewerky, Email: henokessete@hust.edu.cn.

Sherif Babatunde Adeyemi, Email: adeyemi.sb@unilorin.edu.ng.

References

- Abdel-Magied EM, Abdel-Rahman HA, Harraz FM. The effect of aqueous extracts of Cynomorium coccineum and Withania somnifera on testicular development in immature Wistar rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abhilash PC, Jamil S, Singh V, Singh A, Singh N, Srivastava SC. Occurrence and distribution of hexachlorocyclohexane isomers in vegetation samples from a contaminated area. Chemosphere. 2008;72(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari PP, Talukdar S, Borah A. Ethnomedicobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants used for the treatment of reproductive problems in Nalbari district, Assam, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;210:386–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari L, Kotiyal R, Pandey M, Bharkatiya M, Sematy A, Semalty M. Effect of geographical location and type of extract on total phenol/flavon contents and antioxidant activity of different fruits extracts of Withania somnifera. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2020;17(1):92–99. doi: 10.2174/1570163815666180807100456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afewerky HK. Pathology and pathogenicity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Exp Biol Med (maywood) 2020;245(15):1299–1307. doi: 10.1177/1535370220942126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afewerky HK, Lu Y, Zhang T, Li H (2016) Roles of sodium-calcium exchanger isoform-3 toward calcium ion regulation in Alzheimers disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis Parkinsonism 6(7). 10.4172/2161-0460.1000291

- Afewerky HK, Li H, Pang P, Zhang T, Lu Y (2019) Contribution of sodium-calcium exchanger isoform-3 in Aβ 1–42 induced cell death. Neuropsychiatry (London) 9(2):2220–2227. 10.37532/1758-2008.2019.9(2).567

- Agarwal A, Saleh RA, Bedaiwy MA. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(4):829–843. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04948-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad MK, Mahdi AA, Shukla KK, Islam N, Rajender S, Madhukar D, Shankhwar SN, Ahmad S. Withania somnifera improves semen quality by regulating reproductive hormone levels and oxidative stress in seminal plasma of infertile males. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(3):989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam N, Hossain M, Khalil MI, Moniruzzaman M, Sulaiman SA, Gan SH. High catechin concentrations detected in Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) by high performance liquid chromatography analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam N, Hossain M, Mottalib MA, Sulaiman SA, Gan SH, Khalil MI. Methanolic extracts of Withania somnifera leaves, fruits and roots possess antioxidant properties and antibacterial activities. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamgeer YW, Asif H, Sharif A, Riaz H, Bukhari IA, Assiri AM. Traditional medicinal plants used for respiratory disorders in Pakistan: a review of the ethno-medicinal and pharmacological evidence. Chin Med. 2018;13:48. doi: 10.1186/s13020-018-0204-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alebie G, Urga B, Worku A. Systematic review on traditional medicinal plants used for the treatment of malaria in Ethiopia: trends and perspectives. Malar J. 2017;16(1):307. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1953-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qura'n S. Ethnopharmacological survey of wild medicinal plants in Showbak. Jordan J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony ML, Lee J, Hahm ER, Kim SH, Marcus AI, Kumari V, Ji X, Yang Z, Vowell CL, Wipf P, Uechi GT, Yates NA, Romero G, Sarkar SN, Singh SV. Growth arrest by the antitumor steroidal lactone withaferin A in human breast cancer cells is associated with down-regulation and covalent binding at cysteine 303 of beta-tubulin. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(3):1852–1865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.496844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aphale AA, Chibba AD, Kumbhakarna NR, Mateenuddin M, Dahat SH. Subacute toxicity study of the combination of ginseng (Panax ginseng) and ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) in rats: a safety assessment. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;42:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aye MM, Aung HT, Sein MM, Armijos C (2019) A review on the phytochemistry, medicinal properties and pharmacological activities of 15 selected Myanmar medicinal plants. Molecules 24(2). 10.3390/molecules24020293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Aziz MA, Khan AH, Adnan M, Ullah H. Traditional uses of medicinal plants used by indigenous communities for veterinary practices at Bajaur Agency, Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz MA, Khan AH, Ullah H, Adnan M, Hashem A, Abd-Allah EF. Traditional phytomedicines for gynecological problems used by tribal communities of Mohmand Agency near the Pak-Afghan border area. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia-Brazilian Journal of Pharmacognosy. 2018;28(4):503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azgomi RND, Zomorrodi A, Nazemyieh H, Fazljou SMB, Bazargani HS, Nejatbakhsh F, Jazani AM, AsrBadr YA (2018) Effects of Withania somnifera on reproductive system: a systematic review of the available evidence. Biomed Res Int 2018. 10.1155/2018/4076430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baek SC, Lee S, Kim S, Jo MS, Yu JS, Ko YJ, Cho YC, Kim KH (2019) Withaninsams A and B: phenylpropanoid esters from the roots of Indian ginseng (Withania somnifera). Plants (Basel) 8(12). 10.3390/plants8120527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ben BW, El Bouzidi L, Nuzillard JM, Cretton S, Saraux N, Monteillier A, Christen P, Cuendet M, Bekkouche K. Bioactive metabolites from the leaves of Withania adpressa. Pharm Biol. 2018;56(1):505–510. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2018.1499781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia A, Bharti SK, Tewari SK, Sidhu OP, Roy R. Metabolic profiling for studying chemotype variations in Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal fruits using GC-MS and NMR spectroscopy. Phytochemistry. 2013;93:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal AM, Jabeena K, Nisar AM, Tanvir-ul H, Sushma K. Botanical, chemical and pharmacological review of Withania somnifera (Indian ginseng): an ayurvedic medicinal plant. Indian J Drugs Dis. 2012;1(6):147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Birla H, Keswani C, Rai SN, Singh SS, Zahra W, Dilnashin H, Rathore AS, Singh SP. Neuroprotective effects of Withania somnifera in BPA induced-cognitive dysfunction and oxidative stress in mice. Behav Brain Funct. 2019;15(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12993-019-0160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht P, Rawat V. Antibacterial activity of Withania somnifera against Gram-positive isolates from pus samples. Ayu. 2014;35(3):330–332. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.153757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragoszewski P, Turek M, Chacinska A (2017) Control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Open Biol 7(4). 10.1098/rsob.170007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buchter D, Behre HM, Kliesch S, Nieschlag E. Pulsatile GnRH or human chorionic gonadotropin/human menopausal gonadotropin as effective treatment for men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: a review of 42 cases. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;139(3):298–303. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1390298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkill HM (1985) The useful plants of West Tropical Africa, vol 5, 2 edn. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

- Bussmann RW, Glenn A. Medicinal plants used in Northern Peru for reproductive problems and female health. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:47. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario M, Cuellar E, Reyes-Ruiz JM, Darabedian N, Feimeng Z, Miledi R, Russo-Neustadt A, Limon A. Direct evidence for GABAergic activity of Withania somnifera on mammalian ionotropic GABAA and GABArho receptors. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;171:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar K, Kapoor J, Anishetty S. A prospective, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of a high-concentration full-spectrum extract of ashwagandha root in reducing stress and anxiety in adults. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(3):255–262. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Srivastava S, Khalid A, Singh N, Sangwan RS, Sidhu OP, Roy R, Khetrapal CL, Tuli R. Comprehensive metabolic fingerprinting of Withania somnifera leaf and root extracts. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(10):1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan NS, Sharma V, Dixit VK, Thakur M. A review on plants used for improvement of sexual performance and virility. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:868062. doi: 10.1155/2014/868062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Fu AKY, Ip NY. Synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;195:186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Tan J, Wan Z, Zou Y, Afewerky HK, Zhang Z, Zhang T (2017) Effects of commonly used pesticides in China on the mitochondria and ubiquitin-proteasome system in Parkinson's disease. Int J Mol Sci 18(12). 10.3390/ijms18122507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chengappa KN, Bowie CR, Schlicht PJ, Fleet D, Brar JS, Jindal R. Randomized placebo-controlled adjunctive study of an extract of Withania somnifera for cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):1076–1083. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary D, Bhattacharyya S, Joshi K. Body weight management in adults under chronic stress through treatment with Ashwagandha root extract: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22(1):96–106. doi: 10.1177/2156587216641830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary B, Shetty A, Langade DG (2015) Efficacy of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera [L.] Dunal) in improving cardiorespiratory endurance in healthy athletic adults. Ayu 36(1):63–68. 10.4103/0974-8520.169002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Choudhary D, Bhattacharyya S, Bose S (2017a) Efficacy and safety of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal) root extract in improving memory and cognitive functions. J Diet Suppl 14(6):599–612. 10.1080/19390211.2017.1284970 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chukwuma CI, Matsabisa MG, Ibrahim MA, Erukainure OL, Chabalala MH, Islam MS. Medicinal plants with concomitant anti-diabetic and anti-hypertensive effects as potential sources of dual acting therapies against diabetes and hypertension: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;235:329–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar NJ, Hamid A, Ahmad M. Pharmacologic overview of Withania somnifera, the Indian ginseng. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(23):4445–4460. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar NJ, Bhat JA, Satti NK, Sharma PR, Hamid A, Ahmad M. Withanone, an active constituent from Withania somnifera, affords protection against NMDA-induced excitotoxicity in neuron-like cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(7):5061–5073. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar PA, Mir SA, Bhat JA, Hamid A, Singh LR, Malik F, Dar TA. An anti-cancerous protein fraction from Withania somnifera induces ROS-dependent mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;135:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Irani N, Balkrishnan R, Benny IR. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study to evaluate the effects of ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract on sleep quality in healthy adults. Sleep Med. 2020;72:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dold AP, Cocks ML. The medicinal use of some weeds, problem and alien plants in the Grahamstown and Peddie districts of the Eastern Cape, South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2000;96(9–10):467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Dongre S, Langade D, Bhattacharyya S. Efficacy and safety of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root extract in improving sexual function in women: a pilot study. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:284154. doi: 10.1155/2015/284154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugger BN, Dickson DW (2017) Pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 9(7). 10.1101/cshperspect.a028035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Duke JA, Bogenschutz-Godwin MJ, duCellier J, Duke P-AK (1985) Handbook of medicinal herbs, 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

- Durg S, Shivaram SB, Bavage S. Withania somnifera (Indian ginseng) in male infertility: An evidence-based systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2018;50:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzoyem J, Tshikalange E, Kuete V (2013) Medicinal plant research in Africa. Pharmacology and chemistry, 1st edn. Elsevier,

- Elizabeth MW, Dabur AL. Major herbs of ayurveda. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eshetu GR, Dejene TA, Telila LB, Bekele DF (2015) Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants: preparation and application methods by traditional healers in selected districts of southern Ethiopia. Vet World 8(5):674–684. 10.14202/vetworld.2015.674-684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fuladi S, Emami SA, Mohammadpour AH, Karimani A, Manteghi AA, Sahebkar A. Assessment of the efficacy of Withania somnifera root extract in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo- controlled trial. Curr Rev Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2021;16(2):191–196. doi: 10.2174/1574884715666200413120413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzera M, Choudhary MI, Khan IA. Quantitative HPLC analysis of withanolides in Withania somnifera. Fitoterapia. 2003;74(1–2):68–76. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaurav N, Kumari A, Tyagi M, Kumarz D, Chauhuan U, Singh A (2015) Morphology of Withania somnifera (distribution, morphology, phytosociology of Withania somnifera L. Dunal). Int J Current Sci Res 1(7):164–173

- Giday M, Asfaw Z, Elmqvist T, Woldu Z. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Zay people in Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotter E, Abraham A, Gunzberg G, Kirson I. Naturally occurring steroidal lactones with a 17-oriented side chain structure of withanolide E and related compounds. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1977;1(6):341–346. doi: 10.1039/P19770000341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glotter E, Kirson I, Abraham A, Lavie D (1973) Constituents of Withania somnifera Dun-XIII: The withanolides of chemotype III. Tetrahedron 29(10). 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)83156-2

- Gokaraju GR, Gokaraju RR, Bhupathiraju K, Somepalli V, Golakoti T, Gokaraju VK, Venkateswarlu S (2020) Enriched Withania somnifera extract composition used as dry powder form, liquid form, beverage, food product, or dietary supplement for improving testosterone levels, and energy levels, comprises withanolide glycosides and aglycones

- Grierson DS, Afolayan AJ. An ethnobotanical study of plants used for the treatment of wounds in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67(3):327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Mahdi AA, Shukla KK, Ahmad MK, Bansal N, Sankhwar P, Sankhwar SN. Efficacy of Withania somnifera on seminal plasma metabolites of infertile males: a proton NMR study at 800 MHz. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149(1):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Kaur G (2019) Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal ameliorates neurodegeneration and cognitive impairments associated with systemic inflammation. BMC Complement Altern Med 19(1):217. 10.1186/s12906-019-2635-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hahm ER, Lee J, Singh SV. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases and Mcl-1 in apoptosis induction by withaferin A in human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53(11):907–916. doi: 10.1002/mc.22050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashempur MH, Khademi F, Rahmanifard M, Zarshenas MM. An evidence-based study on medicinal plants for hemorrhoids in Medieval Persia. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22(4):969–981. doi: 10.1177/2156587216688597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan-Abdallah A, Merito A, Hassan S, Aboubaker D, Djama M, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E. Medicinal plants and their uses by the people in the Region of Randa. Djibouti J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(2):701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idowu JS, Wilfred OM. Plants used for cosmetics in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: a case study of skin care. Pharmacogn Rev. 2018;12(24):139–156. doi: 10.4103/phrev.phrev_9_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilayperuma I, Ratnasooriya WD, Weerasooriya TR. Effect of Withania somnifera root extract on the sexual behaviour of male rats. Asian J Androl. 2002;4(4):295–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwu MM (2014) Handbook of African medicinal plants. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton

- James AD. Handbook of medicinal herbs. New York: CRC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jana SN, Charan SM. Health benefits and medicinal potency of Withania somnifera: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2018;48(1):22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jayanta KP, Gitishree D, Siyoung L, Seok SK, Han SS. Selected commercial plants: a review of extraction and isolation of bioactive compounds and their pharmacological market value. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;82(1):89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Sanchez M, Licitra F, Underwood BR, Rubinsztein DC (2017) Huntington's disease: Mechanisms of pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7(7). 10.1101/cshperspect.a024240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jon B. The Global Ashwagandha MARKET. Ashwagandha Adv. 2017;1(9):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspate D, Ziyaurrahman AR, Saldanha T, More P, Toraskar S, Darak K, Rohankhedkar S, Narkhede S (2015) To study an aphrodisiac activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Withania Somnifera dried roots in female Wistar rats. Int J Pharm Sci Res 6(7):2820–2836. 10.13040/Ijpsr.0975-8232.6(7).2820-36

- Kataria H, Gupta M, Lakhman S, Kaur G. Withania somnifera aqueous extract facilitates the expression and release of GnRH: In vitro and in vivo study. Neurochem Int. 2015;89:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G, Singh N, Samuel SS, Bora HK, Sharma S, Pachauri SD, Dwivedi AK, Siddiqui HH, Hanif K. Withania somnifera shows a protective effect in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Pharm Biol. 2015;53(1):147–157. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.912240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil MI, Ahmmed I, Ahmed R, Tanvir EM, Afroz R, Paul S, Gan SH, Alam N. Amelioration of isoproterenol-induced oxidative damage in rat myocardium by Withania somnifera leaf extract. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:624159. doi: 10.1155/2015/624159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiasalari Z, Khalili M, Aghaei M. Effect of Withania somnifera on levels of sex hormones in the diabetic male rats. Iran J Reprod Med. 2009;7(4):163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Singh SV. Mammary cancer chemoprevention by withaferin A is accompanied by in vivo suppression of self-renewal of cancer stem cells. Cancer Prev Res (phila) 2014;7(7):738–747. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Yu JS, Lee JY, Choi SU, Lee J, Kim KH. Cytotoxic withanolides from the roots of Indian ginseng (Withania somnifera) J Nat Prod. 2019;82(4):765–773. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Singh KB, Hahm ER, Lokeshwar BL, Singh SV. Withania somnifera root extract inhibits fatty acid synthesis in prostate cancer cells. J Tradit Complement Med. 2020;10(3):188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipkore W, Wanjohi B, Rono H, Kigen G. A study of the medicinal plants used by the Marakwet Community in Kenya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SK, Dhir A. Withania somnifera: an Indian ginseng. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1093–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Kumar A. Possible neuroprotective effect of Withania somnifera root extract against 3-nitropropionic acid-induced behavioral, biochemical, and mitochondrial dysfunction in an animal model of Huntington's disease. J Med Food. 2009;12(3):591–600. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha S, Betsy A, Chawla P. Effect of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root powder supplementation in treatment of hypertension. Stud Ethno Med. 2012;6(2):111–115. doi: 10.1080/09735070.2012.11886427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyathanahalli CN, Manjunath MJ. Oral supplementation of standardized extract of Withania somnifera protects against diabetes-induced testicular oxidative impairments in prepubertal rats. Protoplasma. 2014;251(5):1021–1029. doi: 10.1007/s00709-014-0612-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie D, Kirson I, Glotter E, Rabinovich D, Shakked Z. Crystal and molecular structure of withanolide E, a new natural steroidal lactone with a 17-side chain. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1972;15:877–878. doi: 10.1039/C39720000877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie D, Kirson I, Glotter E (1968) Constituents of Withania somnifera Dun. Part X*: the structure of withanolide D. Israel J Chem 6(Felix Bergmann Anniversary Issue):671–678. 10.1002/ijch.196800085

- Lee J, Sehrawat A, Singh SV. Withaferin A causes activation of Notch2 and Notch4 in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(1):45–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2239-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kim JE, Jang YJ, Lee CC, Lim TG, Jung SK, Lee E, Lim SS, Heo YS, Seo SG, Son JE, Kim JR, Lee CY, Lee HJ, Lee KW. Dehydroglyasperin C suppresses TPA-induced cell transformation through direct inhibition of MKK4 and PI3K. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55(5):552–562. doi: 10.1002/mc.22302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay TJ, Vitrikas KR. Evaluation and treatment of infertility. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(5):308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:139–148. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Malvi H, Kodgule R. An investigation into the stress-relieving and pharmacological actions of an ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Medicine (baltimore) 2019;98(37):e17186. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabona U, Van SF. Southern African medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases. S Afr J Bot. 2013;87:175–193. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2013.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaman YAR, Huang F, Afewerky HK, Maibouge TMS, Ghose B, Wang X. Involvement of calpain in the neuropathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Med Res Rev. 2019;39(2):608–630. doi: 10.1002/med.21534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi AA, Shukla KK, Ahmad MK, Rajender S, Shankhwar SN, Singh V, Dalela D. Withania somnifera improves semen quality in stress-related male fertility. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheswari P, Harish S, Navaneethan M, Muthamizhchelvan C, Ponnusamy S, Hayakawa Y. Bio-modified TiO2 nanoparticles with Withania somnifera, Eclipta prostrata and Glycyrrhiza glabra for anticancer and antibacterial applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;108:110457. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed M, Kalyanam N, Pandey A, Bani S (2019) Aphrodisiac composition useful for managing or treating male sexual dysfunction and associated disorders, comprises Withania somnifera, Mucuna pruriens, Coleus forskohlii, Kaempferia parviflora and Piper nigrum extracts

- Mali PC, Singh AR, Verma MK, Chahar MK, Dobhal MP. Contraceptive effects of withanolide-a in adult male albino rats. Adv Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16(1):31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mamidi P, Thakar AB (2011) Efficacy of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera Dunal. Linn.) in the management of psychogenic erectile dysfunction. Ayu 32(3):322–328. 10.4103/0974-8520.93907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mamta T, Vijaya T. Therapeutic recognition of nutraceuticals for health benefits and economic uplifment of farming community. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2018;7(8):4718–4726. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.708.496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]