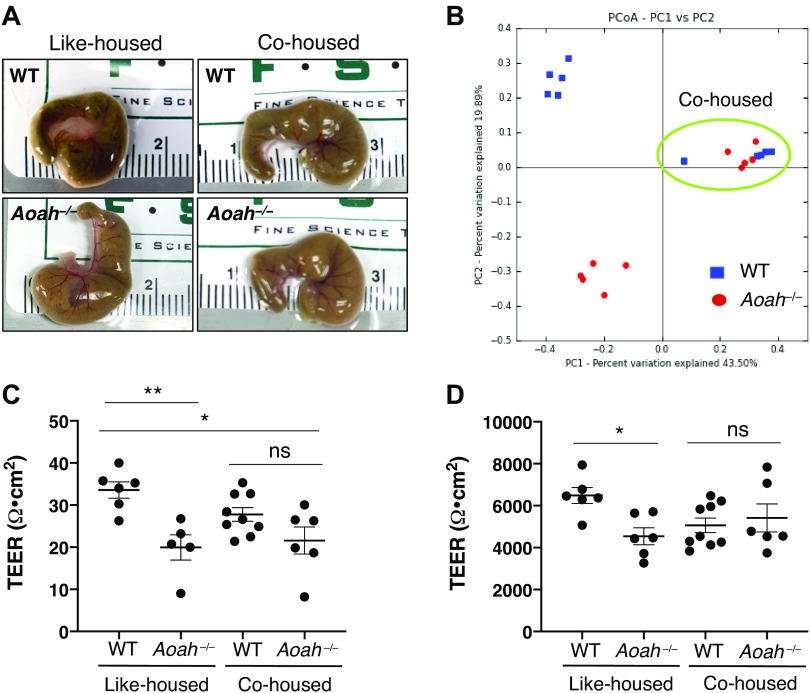

Figure 6.

Converging microbiota by cohousing results in altered gut morphology and TEER. A: comparison of representative cecum sizes of female WT (top left), Aoah−/− (bottom left), cohoused WT (top right), and cohoused Aoah−/− (bottom right) mice. B: principle component analysis (PCoA) plot of 16S rRNA analyses of fecal stool in like-housed and cohoused animals. Dots represent individual mice; AOAH-deficient mice are shown in red and wild-type mice are shown in blue. n = 5 for like-housed conditions and n = 10 for cohoused condition (circled in green). C: Aoah−/− mice showed an improvement in cecum TEER after cohousing (like-housed WT mice: n = 6, like-housed Aoah−/− mice: n = 5, cohoused WT mice: n = 8, cohoused Aoah−/− mice: n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s HSD). Data are represented as individual values and average (represented by horizontal line) ± SE. D: Aoah−/− mice showed an improvement in bladder TEER after cohousing (like-housed WT mice: n = 6, like-housed Aoah−/− mice: n = 6, cohoused WT mice: n = 9, cohoused Aoah−/− mice: n = 6; *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s HSD). Data are represented as individual values and average (represented by horizontal line) ± SE. AOAH, acyloxyacyl hydrolase; HSD, honestly significant difference; ns, not significant; PC1, principal component 1; PC2, principal component 2; TEER, transepithelial electrical resistance; WT, wild type.