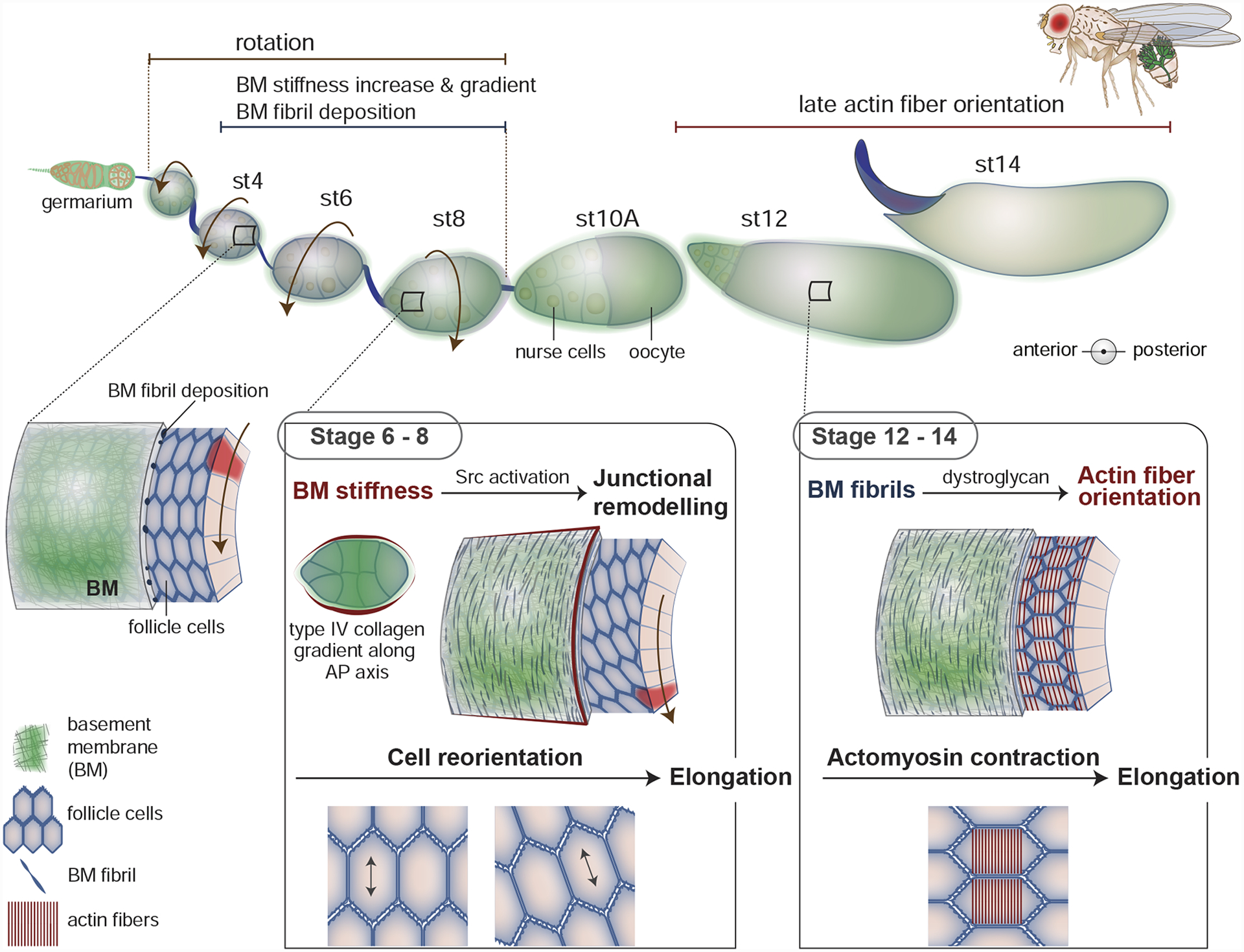

Figure 2. Basement membrane (BM) physical properties help drive Drosophila follicle elongation.

The Drosophila follicle (egg chamber) is initially small and spherical, but dramatically expands in volume and elongates along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis during its 14 stages of development. A key driver of elongation is the BM surrounding the follicle. During stages 1–8 the follicle cells collectively migrate, causing the egg chamber to rotate within its encasing BM. As the chamber rotates, the follicular epithelium deposits more planar BM as well as BM fibrils (first seen at stage 4) that embed within the planar BM and orient perpendicular to the AP axis. Also, a gradient of type IV collagen forms along the AP axis, with increased levels in the central region that tapper at both poles. The overall increase in BM deposition, fibril formation, and the gradient of type IV collagen increases BM stiffness and creates a BM stiffness gradient. During stages 6–8 the softer BM in the anterior region of the follicle is translated into appropriate Src activation, which alters junctional E-cadherin trafficking and facilitates the reorientation cells such that their long axis is more parallel to the AP axis. This reorientation helps promote follicle elongation. In addition, during stages 12–14, the follicle cells, through the dystroglycan matrix receptor, use the orientation of the BM fibrils to guide the alignment of F-actin stress fibers, which promotes later follicle elongation.