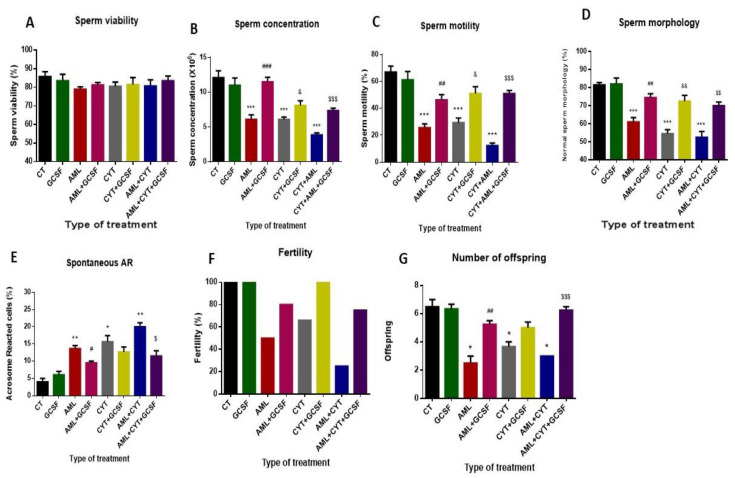

Figure 3.

Effect of GCSF on sperm parameters, fertility capacity and number of offspring in AML- and CYT-treated groups. Mice were treated as described in Figure 2. Sperm were extracted from the epididymis 3 weeks post-treatment. Sperm concentration (A) was evaluated using a Makler counting chamber and determined according to WHO criteria. Sperm motility/immotility was evaluated using a Makler counting chamber and determined as a percentage of total sperm according to WHO criteria (B). Sperm morphology was evaluated following staining with Diff-Quick stain as described previously [18]. Cells were divided into normal and abnormal morphology, which includes: abnormal neck, abnormal tail, abnormal head according to WHO criteria. The percentage of sperm with normal morphology was calculated (C). Spontaneous AR was evaluated as described previously [21]. Sperm that were extracted from the epididymis were stained by fluorescein (FITC) staining. Acrosome reacted (without green staining) and non-reacted sperm (with green staining) were counted, and the percent of sperm that underwent spontaneous acrosome reaction was calculated (D). Viability of sperm cells was evaluated by their staining with 1% Eosin staining. Dead cells were stained in red color. The percent of live sperm cells was calculated (E). To examine the fertility capacity and offspring, two weeks post-treatment, a single male from each group was mated with two females. After two weeks, the females were separated, each to a single cage. The percentage of pregnant females (F) and the number of offspring from each female were counted after five weeks (G). The results are representative of three independent experiments with 5 mice in each group per experiment. *—significant compared to control (CT). #—significant compared to AML, &—significant compared to CYT, $—significant compared to AML + CYT. *,#,&,$—p < 0.05; **,##,&&,$$—p < 0.01; ***,###,$$$—p < 0.001.