Abstract

The harsh realities of racial inequities related to COVID-19 and civil unrest following police killings of unarmed Black men and women in the United States in 2020 heightened awareness of racial injustices around the world. Racism is deeply embedded in academic medicine, yet the nobility of medicine and nursing has helped health care professionals distance themselves from racism.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), like many U.S. academic medical centers, affirmed its commitment to racial equity in summer 2020. A Racial Equity Task Force was charged with identifying barriers to achieving racial equity at the medical center and medical school and recommending key actions to rectify long-standing racial inequities. The task force, composed of students, staff, and faculty, produced more than 60 recommendations, and its work brought to light critical areas that need to be addressed in academic medicine broadly. To dismantle structural racism, academic medicine must: (1) confront medicine’s racist past, which has embedded racial inequities in the U.S. health care system; (2) develop and require health care professionals to possess core competencies in the health impacts of structural racism; (3) recognize race as a sociocultural and political construct, and commit to debiologizing its use; (4) invest in benefits and resources for health care workers in lower-paid roles, in which racial and ethnic minorities are often overrepresented; and (5) commit to antiracism at all levels, including changing institutional policies, starting at the executive leadership level with a vision, metrics, and accountability.

The nobleness of medicine and nursing has long provided a cover for health care professionals to distance themselves from racism. Despite the intractability of racial and ethnic health disparities, many health care professionals blame patient behaviors, education, and economic factors for these differences, often failing to consider their own biases and complicity with structural racism. However, the harsh realities of racial inequities related to COVID-19 and the widespread civil unrest in the United States in 2020 following the murders of unarmed Black men and women were impossible to ignore. Video of the brutal 9 minutes and 29 seconds of George Floyd’s murder and accounts of Breonna Taylor’s murder after being violently awakened in her home—both at the hands of police—heightened awareness of racial injustices around the world. In addition, dramatic increases in hate crimes against Asian Americans linked to xenophobic COVID-19 narratives further exposed the racist underpinnings of U.S. society, including those of medicine.

A Strategic Approach to Racial Equity

In summer 2020, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), like many U.S. academic medical centers, publicly pledged to confront the enduring legacy of racism, including the structures and systems that disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities and drive health inequities. 1 A Racial Equity Task Force, led by faculty, staff, and medical student co-chairs (M.R.D., M.W., and K.K.), was charged with identifying barriers to achieving racial equity at VUMC and Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and recommending key actions to rectify long-standing inequities. More than 100 task force and work group members were appointed, including nurses, physicians, scientists, departmental and hospital leaders, and representatives from human resources, food services, environmental services, and campus police.

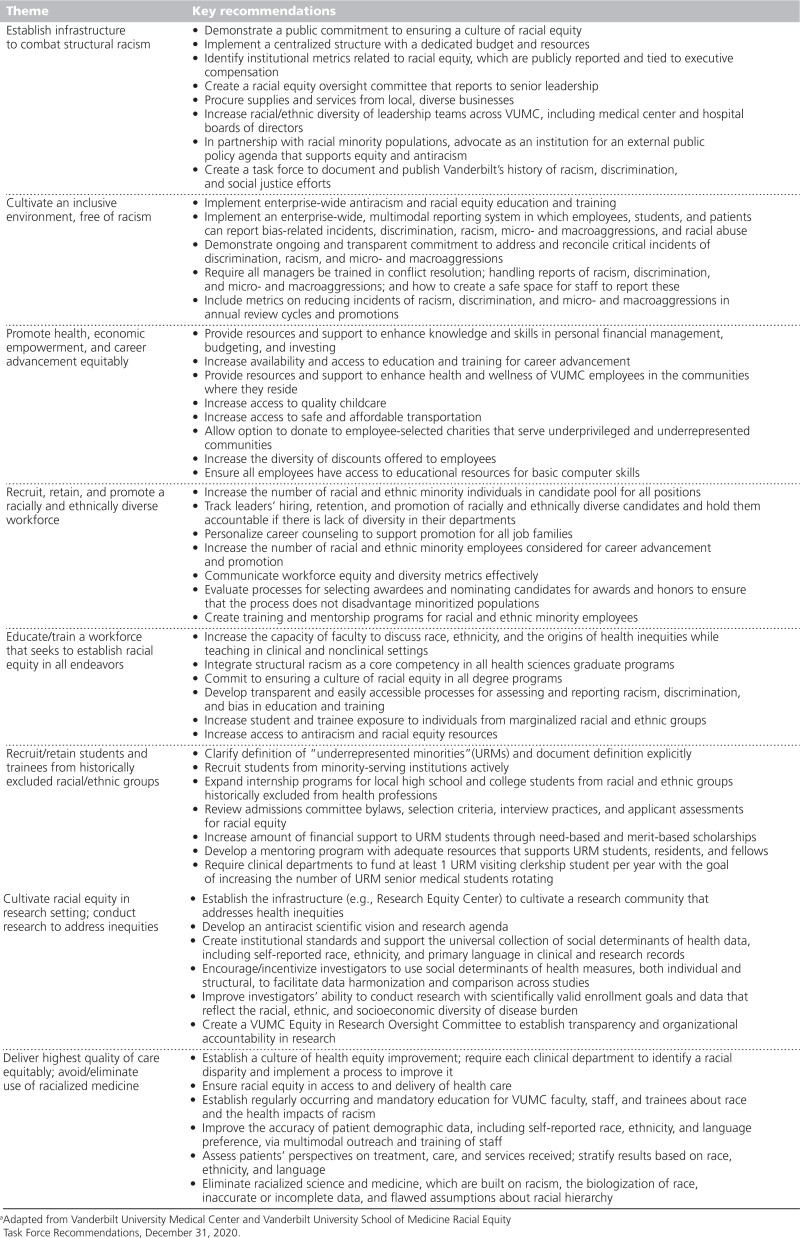

Over the course of 5 months, the task force reviewed existing data and publications and conducted surveys and interviews. The task force sought input from staff, students, trainees, and faculty and used intentional strategies, such as small-group listening sessions, to elicit critical feedback from racial and ethnic groups who have historically been excluded from these conversations. Collaboration across disciplines and roles was a high priority; thus, work groups were composed of and co-led by staff, students, and faculty from across the academic medical center. The final task force report included 62 recommendations with 152 subrecommendations across 8 thematic areas (for key recommendations and themes, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Key Recommendations From Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and School of Medicine’s Racial Equity Task Force Organized by 8 Thematic Categoriesa

The data, deliberations, and courageous conversations resulting from the Racial Equity Task Force’s work brought to light critical areas that need to be addressed not just at VUMC, but in academic medicine broadly. As we discuss below, to dismantle structural racism in academic medical centers, we must:

confront medicine’s racist past, which is the foundation for the inequities embedded in the U.S. health care system;

develop and require health care professionals to possess core competencies specific to the health impacts of structural racism;

recognize race as a sociocultural and political construct, not based on biology or genetics;

invest in benefits and resources to increase the economic empowerment and improve the health of racial and ethnic minority health care workers who are overrepresented in lower-paid roles (e.g., certified nursing assistants, food services staff, and environmental services staff); and

commit to antiracism at all levels, starting with a vision and accountability at the executive leadership level.

Academic Medicine’s Racist History and the Health Impacts of Structural Racism

The scarcity of Indigenous, African American, and Hispanic/Latino health care professionals is not an accident but rather the result of long-standing discriminatory practices. In the early 20th century, most U.S. medical schools did not admit African Americans and many hospitals granted privileges only to White physicians. 2 African Americans primarily attended historically Black medical schools—either Howard University College of Medicine or Meharry Medical College, the 2 schools that survived the 1910 Flexner Report, 3 which recommended shuttering the other 5 historically Black medical schools. Today, medical schools often celebrate their first African American matriculants yet fail to acknowledge the racist policies and practices that purposefully excluded them for decades. This failure bolsters the myth of meritocracy, which lauds individual achievement, and reinforces narratives that blame racial and ethnic minorities for their underrepresentation in medicine rather than addressing the institutional climate and biased systems built on discriminatory, exclusionary, and unjust practices.

Before the legislation establishing Medicare in 1965, most U.S. hospitals were segregated by race. African American patients on segregated wards faced substandard treatment, exploitation, mistreatment, and experimentation. 4 Months before the July 1966 inauguration of Medicare, more than 4,000 segregated hospitals rapidly desegregated, a requirement to receive Medicare payments. 5 This historic change happened with little fanfare and without substantial efforts to address other discriminatory and racist practices.

To confront structural racism, academic medicine must acknowledge, document, and begin to reconcile its racist past by changing policies and practices that have unjust and negative impacts on racial and ethnic minority communities. Academic medicine must go beyond implicit bias and cultural competency training, which focuses on bias and prejudice at the individual level, to implement curricula on the health impacts of structural racism at the institutional level and to set standard competencies at the national level (e.g., via the Liaison Committee on Medical Education and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). Education and training on racial and ethnic health disparities should recognize the painful legacies of overt racism, abuse, and trauma that continue to negatively impact these communities. For example, health disparities among Native Americans cannot be fully understood or addressed without recognizing that the massacre and forced removal of Indigenous people from their land resulted in a ripple of economic, cultural, and social losses that cumulatively disadvantage them today. 6,7

Debiologizing Race

Despite extensive evidence disputing assertions that race is biologically based, long-held beliefs about innate biological differences between races continue to permeate medicine, health care, and biomedical research. Superficial physical features (i.e., skin color, facial features, and hair texture) used to define racial categories are based on 18th-century pseudoscience, and substantial evidence indicates that humans cannot be inherently grouped based on biologically distinct characteristics or genetic clusters. 8 Although ancestral alleles may be associated with response to medication or disease risk, genetic variation is widely distributed across populations, and greater genetic heterogeneity exists within than between racial and ethnic groups. 9 The racialization of humans has been largely political, not scientific; thus, race is tightly entwined with social and cultural factors and is frequently a proxy for racism, 10 which has biological consequences. Experiences with racism and discrimination are linked to biophysiological changes such as neuroendocrine dysregulation, cellular aging, and elevated inflammatory cytokines, which result in excess morbidity and mortality among those experiencing racism. 11

Physicians and scientists were not passive bystanders in the racialization of humans, which is built on beliefs of White superiority, but rather active participants and, at times, leaders in the development of unsound evidence to support racist ideologies. The study of human genetics is rooted in white supremacy, and prominent scientists like Francis Galton and Charles Davenport promulgated eugenics. 12 Samuel Cartwright, a prominent physician and slaveholder, published papers about decreased lung capacity in enslaved people that purported appropriate treatment to be physical labor under the White man’s control. 13,14 Although lung function is highly variable among individuals, remnants of Cartwright’s flawed evidence continue in guidelines from American and European professional societies for racial and ethnic corrections in spirometry. 15–17

Flawed beliefs about biological race are deeply embedded in medical education, scientific literature, diagnostic tools, and clinical algorithms. To debiologize race and differentiate between race and ancestry, academic medicine should critically evaluate and set standards regarding the use of race in clinical and research settings. Race should be self-reported (allowing multiple responses and using a broad range of options), documented in the social history of clinical and research records, and excluded from the beginning of clinical case presentations. 18 Factors including experiences with racism and social determinants of health should be captured and considered as context for understanding racial differences in health outcomes. As Davis 12 writes, “Human genetics is not strictly a biological science, it is also a social science”; thus, collaborations among geneticists and social scientists that integrate and transcend disciplinary perspectives must guide conceptions about race and genetics.

Academic Medicine’s Workforce: Not Just Physicians and Scientists

The traditional tripartite mission of academic medical centers elevates the voices of faculty who generate income and prestige through clinical care, research, and education. Yet faculty (clinicians, researchers, and educators) represent less than 20% of employees at most academic medical centers and are less likely than nonfaculty employees to reflect the demographics of the broader community. 19 Racial and ethnic minority individuals are more likely to work in entry-level and service roles, 19 due in part to historic policies resulting in residential segregation, underfunded schools, and ongoing disinvestment in communities of color, as well as prior exclusionary hiring practices within hospitals. For example, Vivien Thomas, who is hailed as a surgical pioneer for his role in developing a technique to repair tetralogy of Fallot, was classified as a janitor when he was hired as a laboratory technician in 1930 because janitor was the only classification Vanderbilt University assigned to Black men. 20

Our VUMC Racial Equity Task Force intentionally included nurses, laboratory staff, research assistants, and service workers and provided opportunities for staff to share their views about the institutional climate and their work experiences in a safe environment. They identified limited opportunities for upward mobility and frequent experiences of macro- and microaggressions in the work environment. Staff, particularly those in service roles, reported differential access to and use of employee benefits due to lack of access to technology both at work and home. They also reported having few opportunities to discuss benefits with staff who are bilingual and understand the differing needs and priorities of people from minoritized groups.

Employees of color are overrepresented in lower paying health care positions, 21 which impacts their physical health, financial well-being, and opportunities for career advancement. To advance racial equity, academic medical centers should offer flexible benefits such as childcare subsidies, transportation assistance, educational resources for dependents, and tuition assistance to health care workers in lower-paid roles. Racial and ethnic minority employees also need access to mentoring, skills training, and sponsorship programs. Formal recognition programs should value activities often performed by employees of color, such as community engagement, mentoring other minority employees, and building trust with minority patients. Antiracism training should be required for managers and supervisors to promote a culture of inclusivity and mitigate biased evaluations based on stereotypes and cultural differences.

Leadership Necessary for Culture Change

Transforming institutional culture from being nonracist to being fully inclusive and antiracist requires a long-term commitment and significant investment of time and resources. Committed leaders are crucial to this challenging transformation, and executive leaders must be actively involved in developing and communicating an antiracist vision and setting expectations for accountability. Until recently, discussions of racism and white supremacy have been infrequent in academic medicine. These terms often invoke defensiveness when used as they may be considered personal attacks and not understood as systemic issues. Even as systemic and institutional racism become recognized, many health care professionals will struggle to accept that they are part of a culture that has oppressed and systematically disadvantaged some racial and ethnic groups.

To deconstruct policies and practices that enable systemic racism and subsequently restructure institutions, leaders must have cultural humility, that is, a willingness to learn about the experiences of other cultures as well as to self-critique and examine their own beliefs and cultural identities. 22 Racial equity in leadership must also be a high priority, as it will help institutions achieve the broader goals of delivering high-quality, person-centered care, increasing patient satisfaction, and catalyzing high-impact scientific discoveries. 23–25 Racial and ethnic minority individuals comprise only 11% of health care executives, 14% of hospital board members, and 19% of mid- and first-level managers. 26 Only 3.6% of medical school faculty are African American and 5.5% are Hispanic/Latino. 27 However, these faculty and faculty from other minoritized groups are frequently overtaxed with service on committees, mentoring, and building public trust, often without additional compensation or opportunity for career advancement. 28 Executive leaders should proactively seek leaders from diverse backgrounds who have lived experiences with racism. Cultural differences and life experiences should be viewed as assets, articulated in job descriptions, and valued in assessments for hiring and promotion. Executive leaders must reverse formal and informal practices that have selectively advantaged White individuals and learn from, listen to, and share power with individuals from historically excluded racial and ethnic groups. Leaders should articulate clear goals and metrics for racial equity, which should be tied to executive compensation.

VUMC’s Steps Toward Becoming an Antiracist Academic Medical Center

VUMC’s strides toward eliminating racial and ethnic inequities go beyond our Racial Equity Task Force. Specific actions taken between July 2020 and July 2021 toward becoming an antiracist academic medical center include (1) eliminating race-based glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) reporting; (2) requiring full-day antiracism training for VUMC executive leaders, including department chairs, and members of the VUMC Board of Directors; (3) increasing VUMC’s minimum wage to $15/hour; (4) embedding antiracism training in the first-year medical school curriculum; (5) renaming Dixie Place, a street on campus whose name was a vestige of Southern secessionist states, as Vivien Thomas Way in honor of the African American surgical pioneer; (6) creating new leadership roles to advance racial equity, such as the senior director of nursing diversity and inclusion; and (7) introducing twice monthly discussions with medical education leaders, facilitated by an expert in racial equity, to begin critically reviewing the medical school curriculum for racial and ethnic bias, stereotypes, misinformation, and race-based medicine.

VUMC is committed to continuing these efforts to combat structural racism and will develop a comprehensive equity plan, guided by our Racial Equity Task Force recommendations (Table 1). Leadership is needed at the national level to develop competencies, determine core metrics of success, and share best practices among academic medical centers striving to become antiracist.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the more than 100 students, staff, and faculty who served on the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Racial Equity Task Force. Special thanks to the Office of Health Equity and the Office of Strategy and Innovation for supporting the task force’s work and to executive leaders, including Dr. Jeffrey Balser, Dr. John Manning, Dr. Andre Churchwell, and Dr. Donald Brady, for their commitment to racial equity.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable

Contributor Information

Mamie Williams, Email: mamie.g.williams@vumc.org.

Karampreet Kaur, Email: Karampreet.Kaur@vanderbilt.edu.

Michael R. DeBaun, Email: michael.r.debaun@vumc.org.

References

- 1.Whitney K. Racial Equity Task Force releases initial recommendations. VUMC Reporter. https://news.vumc.org/2021/06/21/racial-equity-task-force-releases-initial-recommendations. Published June 21, 2021. Accessed July 28, 2021

- 2.Washington HA. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans From Colonial Times to the Present. New York, NY: Doubleday Books; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan LW, Suez Mittman I. The state of diversity in the health professions a century after Flexner. Acad Med. 2010; 85:246–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DB. The Power to Heal: Civil Rights, Medicare, and the Struggle to Transform America’s Health Care System. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds PP. The federal government’s use of Title VI and Medicare to racially integrate hospitals in the United States, 1963 through 1967. Am J Public Health. 1997; 87:1850–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011; 8:115–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans-Campbell T. Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. J Interpers Violence. 2008; 23:316–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serre D, Pääbo S. Evidence for gradients of human genetic diversity within and among continents. Genome Res. 2004; 14:1679–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper RS, Kaufman JS, Ward R. Race and genomics. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:1166–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Micheletti SJ, Bryc K, Ancona Esselmann SG, et al. ; 23andMe Research Team. Genetic consequences of the transatlantic slave trade in the Americas. Am J Hum Genet. 2020; 107:265–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338:171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis LK. Human Genetics Needs an Antiracism Plan. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/human-genetics-needs-an-antiracism-plan. Accessed July 19, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger N. Shades of difference: Theoretical underpinnings of the medical controversy on Black/White differences in the United States, 1830–1870. Int J Health Serv. 1987; 17:259–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cartwright SA. Report on the diseases and physical peculiarities of the Negro race. New Orleans Med Surg. 1851; 7:691–715 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200:e70–e88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: The global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012; 40:1324–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun L, Wolfgang M, Dickersin K. Defining race/ethnicity and explaining difference in research studies on lung function. Eur Respir J. 2013; 41:1362–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai J, Ucik L, Baldwin N, Hasslinger C, George P. Race matters? Examining and rethinking race portrayal in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. 2016; 91:916–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dreachslin JL. Diversity leadership and organizational transformation: Performance indicators for health services organizations. J Healthc Manag. 1999; 44:427–439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmermans S. A black technician and blue babies. Soc Stud Sci. 2003; 33:197–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreachslin JL, Weech-Maldonado R, Dansky KH. Racial and ethnic diversity and organizational behavior: A focused research agenda for health services management. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 59:961–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998; 9:117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaVeist TA, Pierre G. Integrating the 3Ds—Social determinants, health disparities, and health-care workforce diversity. Public Health Rep. 2014; 129suppl 29–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dotson E, Nuru-Jeter A. Setting the stage for a business case for leadership diversity in healthcare: History, research, and leverage. J Healthc Manag. 2012; 57:35–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019; 111:383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute for Diversity in Health Management. Diversity and Disparities: A Benchmarking Study of U.S. Hospitals in 2015. https://ifdhe.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/03/Diverity_Disparities2016_final.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed July 19, 2021

- 27.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019. Published 2020. Accessed July 19, 2021

- 28.Williamson T, Goodwin CR, Ubel PA. Minority tax reform—Avoiding overtaxing minorities when we need them most. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384:1877–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]