Abstract

Purpose

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is widely used for pulmonary infection; nonetheless, the experience from its clinical use in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections is sparse. This study aimed to compare mNGS results from lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and determine their clinical diagnostic efficacy.

Patients and Methods

A total of 106 patients with suspected pulmonary fungal infection from May 2018 to January 2020 were included in this retrospective study. All patients’ lung biopsy and BALF specimens were collected through bronchoscopy. Overall, 45 (42.5%) patients had pulmonary fungal infection. The performance of lung biopsy and BALF used for mNGS in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections and identifying pathogens was compared. Additionally, mNGS was compared with conventional tests (pathology, galactomannan test, and cultures) with respect to the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections.

Results

Lung biopsy-mNGS and BALF-mNGS exhibited no difference in terms of sensitivity (80.0% vs 84.4%, P=0.754) and specificity (91.8% vs 85.3%, P=0.39). Additionally, there was no difference in specificity between mNGS and conventional tests; however, the sensitivity of mNGS (lung biopsy, BALF) in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections was significantly higher than that of conventional tests (conventional tests vs biopsy-mNGS: 44.4% vs 80.0%, P<0.05; conventional tests vs BALF-mNGS: 44.4% vs 84.4%, P<0.05). Among 32 patients with positive mNGS results for both biopsy and BALF specimens, 23 (71.9%) cases of consistency between the two tests for the detected fungi and nine (28.1%) cases of a partial match were identified. Receiver operating curve analysis revealed that the area under the curve for the combination of biopsy and BALF was significantly higher than that for BALF-mNGS (P=0.018).

Conclusion

We recommend biopsy-based or BALF-based mNGS for diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections because of their diagnostic advantages over conventional tests. The combination of biopsy and BALF for mNGS can be considered when higher diagnostic efficacy is required.

Keywords: mNGS, diagnosis, sensitivity, specificity

Introduction

In recent years, with the increase in high-risk groups requiring immunosuppressant use, the prevalence of pulmonary fungal disease has shown a significant upward trend. The main sources of fungal infections in human lungs are opportunistic fungi: Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Pneumocystis jirovecii, and endemic fungi. Among them, Aspergillus and Cryptococcus are the main fungal pathogens associated with lung infections.1 Microscopic smears and cultures are conventional microbial methods used for pathogen identification; however, both methods are time consuming and not highly sensitive. The gold standard for the detection of invasive fungal infections is histopathological diagnosis. However, it is time consuming, it cannot identify pathogens, and it has low sensitivity. For Aspergillus infections, the positive predictive value (PPV) of respiratory specimen cultures obtained by sputum induction or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is low (approximately 72%).2 When testing patients with non-hematological diseases or those who have been treated with antifungal drugs, the PPV may be even lower.3 Clinically, BALF’s galactomannan (GM) test results are affected by various factors, which can lower the sensitivity and increase the false positivity rate.4–7

Since the conventional tests for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections have a low sensitivity and are influenced by various factors, there is an urgent need for new technology with a higher sensitivity for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections. Currently, metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is a widely used method for the clinical detection of pathogens and has obvious advantages in pathogen detection.8 One study showed that mNGS can improve the sensitivity of pathogen detection and that it is less affected by antibiotic exposure before detection.9 In the studies that used mNGS for the detection of lung infections,10–13 there have been advantages identified over traditional detection methods, indicating that mNGS can be used to detect lung infections. However, there is limited experience from the clinical use of mNGS in the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections.

In this study, we used bronchoscopy to obtain lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS from 106 patients with suspected pulmonary fungal infection to identify pathogens. We compared the mNGS results from lung biopsy and BALF to specifically determine the difference between the two mNGS results and the clinical diagnostic efficacy. Additionally, mNGS (BALF) was compared with conventional tests (pathology, GM test, and cultures).

Patients and Methods

Specimen Collection and Processing

The present study is a retrospective cohort study. Patients admitted to the Respiratory Department at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital for suspected pulmonary fungal infection from May 2018 to January 2020 provided informed consent to undergo bronchoscopy and mNGS. Experienced physicians collected the patient’s lung biopsy and BALF specimens through bronchoscopy based on canonical operational procedures.14 During bronchoscopy, the operating physician recorded complications such as bleeding, fatal hemoptysis, arrhythmia, and death. Six to ten lung biopsy specimens collected from the enrolled patients were used for pathology, rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE), and mNGS. Within 2 hours, the lung biopsy specimens were sent to the histopathology laboratory and then processed using standard procedures.15 The remaining lung biopsy specimens were stored at −80°C for mNGS. Part of the BALF was used for fungal and bacterial culture. Another part of the BALF was used for Xpert MTB, GM test, and smear. The remaining BALF specimens were stored at −80°C for mNGS.

mNGS and Analyses

The TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (DP316, TIANGEN BIOTECH) was used to extract the DNA from the BALF and lung biopsy homogenates based on the company’s recommendation. DNA libraries were constructed based on the Beijing Genomics Institute sequencer-100. By removing low-quality and shorter (<35 bp) readings, high-quality sequencing data were generated. Burrows-Wheeler Aligner software was applied to map to a human reference (hg19) to identify human sequence data. Microbial genome databases were used to classify the remaining data.9,16,17 The classification reference databases were downloaded from NCBI (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/).

Criteria of Diagnosis of Pulmonary Fungal Infection

Pulmonary fungal infection was defined based on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Mycoses Study Group (MSG) criteria.18 In our study, for proven Invasive Fungal Disease (IFDs), histopathological findings of hyphae on lung biopsy were considered an IFI diagnosis, and this criterion was adapted for any patient. For probable IFDs, experts in the respiratory department of our hospital reviewed the chest CT images of pulmonary fungal infection, which was one of the clinical diagnostic criteria, and evaluated possible mycological evidence such as the GM antigen test. Patients with no proven or probable IFDs throughout the study period were categorized as exclude IFDs.

The pathogen responsible for the fungal infections was diagnosed if it met any of the following thresholds. First, culture and/or histopathological examination positive for fungi; it is strongly recommended to use BALF GM to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in immunosuppressed patients.4 Second, at least 50 unique reads from a single species of fungi; for pathogens with unique reads less than 50, the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infection can still be made based on the clinical situation.13

Statistical Analysis

In order to determine the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and negative predictive value (NPV), 2×2 contingency tables were derived. All data are reported as the absolute value of their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Diagnostic accuracy of pulmonary fungal infections based on the fungal reads from mNGS and area under the curve (AUC) was calculated after conducting the corresponding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc 19 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital. The need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and because the data were anonymously analyzed.

Results

Patient Characteristics and mNGS Results

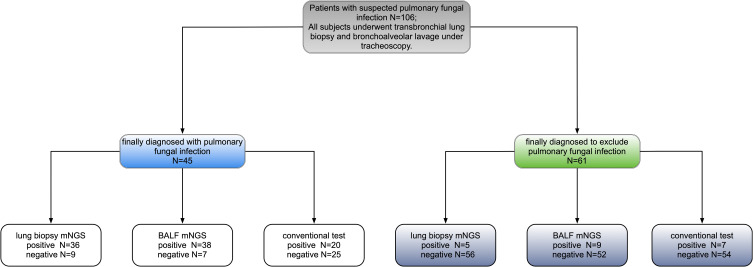

Overall, 106 patients were included in the study; 76 (71.7%) were males, and the average age was 43.2±18.5 years. Eighty-four (79.3%) patients had immunocompromised function, and 79 of them suffered from hematological diseases (Table 1). In total, 45 (42.5%) patients were diagnosed with pulmonary fungal infections (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Patient, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.2±18.5 | |

| Sex | Male | 76 (71.7%) |

| Female | 30 (28.3%) | |

| Underlying disease | Immunocompromised | 84 (79.3%) |

| Non-Immunocompromised | 22 (20.8%) |

Table 2.

| Patient ID | Sex | Age/yr | Underlying Disease | Immunocompromised | Pathology Results | Culture Results | GM Test | mNGS (Biopsy) Based Diagnosis | mNGS (BAL) Based Diagnosis | Final Clinical Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 46 | ALL | Yes | Pink amorphous substance, negative for PAS, hexamine silver and acid-fast staining | Mold growth | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 2 | Male | 19 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 3 | Male | 43 | AML | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 4 | Male | 19 | T lymphoblastic acute leukemia | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 5 | Male | 47 | No | No | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with lymphocyte infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 6 | Male | 63 | No | No | Interstitial fibrous tissue hyperplasia, scattered lymphocyte infiltration, alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, fibroblast thrombosis in the alveolar cavity | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 7 | Female | 14 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with lymphocyte infiltration | Viridans streptococci, Micrococcus pharyngis | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 8 | Male | 11 | Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | Yes | Chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in the alveolar compartment, | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 9 | Female | 39 | Mixed connective tissue disease | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with lymphocyte infiltration | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 10 | Male | 15 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue mild hyperplasia and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, | Negative | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 11 | Male | 25 | ALL | Yes | Interstitial lymphocytes, plasma cell infiltration, neutrophils, fibrinous exudate | Citrobacter koseri | Positive | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 12 | Male | 68 | Pancytopenia | Yes | No | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 13 | Female | 51 | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Yes | Fibrous tissue hyperplasia and lymphoid tissue hyperplasia, | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 14 | Male | 39 | AML | Yes | Widened alveolar space, fibrous tissue hyperplasia, focal alveolar hyperplasia, Scattered lymphocytes and tissue cells infiltration, focal carbon dust deposition | Viridans streptococci, Neisseria sicca | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 15 | Male | 52 | ALL | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 16 | Female | 30 | Chronic gastritis | No | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia, Slurry cellulosic exudate | Citrobacter koseri | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 17 | Male | 32 | AML | Yes | Tumorous lesions to be excluded | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 18 | Male | 56 | ALL | Yes | Mild hyperplasia of alveolar septal fibrous tissue, focal type II alveolar epithelial hyperplasia | Viridans streptococci, Neisseria sicca | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 19 | Male | 22 | ALL | Yes | Necrotic tissue | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 20 | Male | 18 | Acute B lymphocytic lymphoma | Yes | Mild hyperplasia of alveolar septum fibrous tissue | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 21 | Female | 34 | No | No | Mild hyperplasia of alveolar septum fibrous tissue | Viridans streptococci, Staphylococcus epidermidis | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 22 | Male | 58 | MDS | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue proliferates, scattered lymphocytes infiltrate, fibroblast thrombus formation in the alveolar cavity, | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 23 | Male | 68 | AML | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, local alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 24 | Male | 22 | ALL | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 25 | Female | 55 | AML | Yes | Alveolar septum widening, interstitial fibrous tissue hyperplasia with inflammatory cell infiltration | Acinetobacter baumannii complex | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 26 | Male | 48 | AML | Yes | No | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 27 | Female | 63 | AML | Yes | Mold hyphae | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 28 | Male | 60 | AML | Yes | Mucosal lamina propria fibrosis with medium to small nuclei and clusters of cells stained with cytoplasm, not supporting myeloid leukemia cells | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 29 | Male | 47 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia, Foamy cell aggregation, No leukemia cells seen | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 30 | Male | 25 | ALL | Yes | Inflammatory exudate and coagulated necrotic tissue | Meningeal sepsis Eliza Platinum bacteria, Citrobacter koseri | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 31 | Female | 15 | CML | Yes | Coagulating necrotic tissue and very little fibrous tissue | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 32 | Male | 58 | AML | Yes | No tumor cells seen | Pseudomonas putida, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 33 | Male | 18 | ALL | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 34 | Male | 54 | No | No | Chronic inflammation of mucosa | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 35 | Male | 71 | MarginalzoneB-cell lymphoma | Yes | Chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in alveolar space | Viridans Streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 36 | Female | 41 | No | No | Fibroblast thrombus formation in the alveolar cavity | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 37 | Female | 42 | Acute Laryngitis | No | Fibrous tissue hyperplasia and lymphocyte infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 38 | Female | 63 | CML | Yes | Fibrous tissue hyperplasia, with scattered inflammatory cell infiltration | Enterobacter cloacae | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 39 | Male | 22 | ALL | Yes | Interstitial fibrous tissue hyperplasia with inflammatory cell infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 40 | Male | 38 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar septum widening, interstitial fibrous tissue hyperplasia | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 41 | Female | 31 | AML | Yes | Legion of Fungi | Enterobacter cloacae | Positive | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 42 | Female | 64 | Postoperative Breast Tumor | No | Chronic inflammatory cell infiltration with mild fibrous tissue hyperplasia | Viridans Streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 43 | Male | 42 | No | No | Fibroblast thrombus formation in the alveolar cavity | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 44 | Male | 49 | AML | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 45 | Male | 47 | Acute leukemia | Yes | A lot of fungus and a little inflammatory exudate | Staphylococcus aureus | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 46 | Female | 49 | ALL | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 47 | Male | 64 | AML | Yes | Mild proliferation of alveolar septal fibrous tissue with a little lymphocyte infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 48 | Male | 38 | Immunorelated pancytopenia | Yes | Alveolar hemorrhage, edema, and hemosiderin deposition | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 49 | Female | 43 | Asthma | No | Fibroblast plug formation | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 50 | Male | 51 | AML | Yes | No | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 51 | Male | 61 | Diabetes, coronary heart disease | No | Legion of fungi. methenamine silver stain +. | Negative | Positive | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 52 | Male | 23 | ALL | Yes | Non-neoplastic lesions | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 53 | Male | 66 | Hypertension | No | Fibrous tissue hyperplasia and inflammatory cell infiltration of alveolar septum | Micrococcus pharyngis | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 54 | Male | 61 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension | No | Non-small cell carcinoma, predisposing to squamous cell carcinoma | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 55 | Male | 49 | Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | Yes | Powdery cellulose-like exudate, neutrophils, degenerated and necrotic cells | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 56 | Male | 51 | AML | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 57 | Male | 30 | Aplastic anemia | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with lymphocyte infiltration | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 58 | Female | 46 | Hypertension | No | Alveolar septum widening, interstitial fibrous tissue proliferation and inflammatory cell infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Cryptococcal infection |

| 59 | Male | 47 | Aplastic anemia | Yes | Mold clusters, methenamine silver stain + | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 60 | Male | 65 | Hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease | No | Lymphocyte infiltration, acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 61 | Male | 72 | Lung tumor | Yes | Lymphocyte infiltration, alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 62 | Male | 11 | Acute mixed cell leukemia | Yes | Acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration | Viridans streptococci | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 63 | Female | 64 | Diabetes, nodular goiter | No | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration | Escherichia Coli | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 64 | Male | 75 | Acute leukemia | Yes | Chronic inflammation | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 65 | Male | 73 | Acute monocytic leukemia | Yes | Inflammatory cell infiltration | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 66 | Female | 33 | AML | Yes | Acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, virus infection not excluded | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 67 | Female | 18 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, focal fibroblast thrombus formation, mild hyperplasia of alveolar septal fibrous tissue, and organizing lesions not excluded | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 68 | Male | 44 | T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 69 | Female | 10 | Aplastic anemia | Yes | Mesenchymal tissue and large amount of acute exudate | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 70 | Male | 38 | No | No | Lymphocyte infiltration of alveolar septum with fibrous tissue hyperplasia, fibroblast plug | Micrococcus pharyngis | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 71 | Female | 39 | Leukemia | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 72 | Male | 70 | Diabetes, alcoholic cirrhosis | No | No | Viridans streptococci | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 73 | Male | 21 | AML | Yes | No tumor cells | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 74 | Male | 38 | Immunorelated pancytopenia | Yes | Chronic inflammation of the mucosa | Enterococcus faecalis | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 75 | Male | 13 | ALL | Yes | Legion of Fungi | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 76 | Male | 69 | No | No | Chronic inflammation of mucosa | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 77 | Male | 66 | Hypertension | No | Proliferation of interstitial fibrous tissue and lymphoid tissue with scattered inflammatory cell infiltration, | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 78 | Male | 23 | Acute leukemia | Yes | No tumor cells | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 79 | Male | 58 | ALL | Yes | Amorphous tissue, small airway mucosa with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrous tissue proliferation | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 80 | Male | 31 | AML | Yes | No | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 81 | Male | 53 | MDS | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia and local fibroblast thrombus formation. | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 82 | Male | 17 | AML | Yes | No | Candida albicans | Positive | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 83 | Male | 29 | Aplastic anemia | Yes | No | Achromobacter xylosoxidans | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 84 | Male | 43 | ALL | Yes | Suspicious fungus | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 85 | Female | 9 | AML | Yes | No | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 86 | Male | 53 | AML | Yes | No tumor cells seen | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 87 | Male | 66 | No | No | Proliferation of interstitial fibrous tissue with scattered inflammatory cell infiltration, fibroblast plugs, | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 88 | Male | 50 | Hypertension | No | Interstitial fibrous tissue with inflammatory cell infiltration, | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 89 | Female | 59 | Leukemia | Yes | No | C. glabrata, viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 90 | Female | 56 | AML | Yes | Mild hyperplasia of alveolar septum fibrous tissue | Viridans streptococci | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 91 | Male | 48 | Lymphoma, hypertension | Yes | Fibrinous exudative necrosis, a small amount of inflammatory cells and epithelial cells | Mold growth | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 92 | Female | 36 | AML | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 93 | Male | 35 | Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma | Yes | Mild hyperplasia of alveolar septum fibrous tissue | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 94 | Male | 53 | AML | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia | Negative | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 95 | Female | 39 | ALL | Yes | Alveolar septal fibrous tissue hyperplasia, foam-like macrophage aggregation, type II alveolar epithelial hyperplasia | Viridans streptococci, staphylococcus epidermidis | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 96 | Male | 37 | MDS | Yes | Legion of fungi. methenamine silver stain + | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Positive | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 97 | Male | 26 | AML | Yes | Alveolar septal hyperplasia, interstitial fibrous tissue hyperplasia with a small amount of inflammatory cell infiltration | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 98 | Male | 77 | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia | Yes | Granulomatous lesions | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 99 | Male | 25 | ALL | Yes | Immunohistochemical staining excludes leukemia involvement | Viridans streptococci, Pneumocystis carinii | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 100 | Male | 73 | Chronic Myelocytic Leukemia | Yes | Amorphous necrotic tissue with a small amount of neutrophil infiltration | Viridans streptococci, corynebacterium | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 101 | Female | 16 | ALL | Yes | Cellulose exudation and foam cells, lymphocyte infiltration and fibrous tissue proliferation | Mold growth | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 102 | Female | 61 | SLE | Yes | Methenamine silver stain +, cryptococcosis | Negative | Positive | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 103 | Female | 49 | SLE | Yes | No | Mold growth | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 104 | Male | 15 | AML | Yes | Extruded peripheral lung tissue, individual alveolar cavity expansion | Negative | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 105 | Male | 74 | Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Yes | Fungal hyphae and spores, PAS-positive and methenamine silver | Negative | Positive | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 106 | Female | 21 | ALL | Yes | Silk-like structure, histochemical staining shows PAS positive, mold hyphae | Negative | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection | Pulmonary fungal infection |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome.

Figure 1.

Methods used to diagnose pulmonary fungal infections.

Comparison Between mNGS and Conventional Tests

Among the 106 patients with suspected pulmonary fungal infection, the diagnostic efficacy of mNGS for lung biopsy and BALF is shown in Table 3. The sensitivity and specificity of lung biopsy-mNGS for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections were 80.0% (95% CI, 65.0–89.9%) and 91.8% (95% CI, 81.2–96.9%), and the PPV and NPV were 87.8% (95% CI, 73.0–95.4%) and 86.2% (95% CI, 74.8–93.1%), respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of BALF-mNGS for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections were 84.4% (95% CI, 69.9–93.0%) and 85.3% (95% CI, 73.3–92.6%), and the PPV and NPV were 80.9% (95% CI, 66.3–90.4%) and 88.1% (95% CI, 76.5–94.7%), respectively.

Table 3.

Performance of mNGS and the Conventional Test in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Fungal Infections

| Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | P value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mNGS (biopsy) | 80.0a,b (65.0–89.9) | 91.8A,B (81.2–96.9) | 87.8 (73.0–95.4) | 86.2 (74.8–93.1) | 0.754a | 0.388A |

| mNGS (balf) | 84.4a,c (69.9–93.0) | 85.3A,C (73.3–92.6) | 80.9 (66.3–90.4) | 88.1 (76.5–94.7) | 0.002b | 0.774B |

| Conventional test | 44.44b,c (30.0–59.9) | 88.52B,C (77.2–94.9) | 74.1 (53.4–88.1) | 68.4 (56.8–78.1) | 0.0003c | 0.774C |

Notes: Sensitivity: a, biopsy-mNGS vs BALF-mNGS; b, biopsy-mNGS vs conventional test; c, BALF-mNGS vs conventional test. Specificity: A, biopsy-mNGS vs BALF-mNGS; B, biopsy-mNGS vs conventional test; C, BALF-mNGS vs conventional test.

Abbreviations: PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; CI, confidence interval.

The sensitivity and specificity of conventional tests in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections were 44.4% (95% CI, 30.0–59.9%) and 88.5% (95% CI, 77.2–94.9%), whereas the PPV and NPV were 74.1% (95% CI, 53.4–88.1%) and 68.4% (95% CI, 56.8–78.1%), respectively. There was no significant difference in the specificity between mNGS and conventional tests; however, the sensitivity of mNGS (lung biopsy, BALF) in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections was significantly higher than that of conventional tests (conventional tests vs biopsy-mNGS: 44.4% vs 80.0%, P<0.05; conventional tests vs BALF-mNGS: 44.4% vs 84.4%, P<0.05) (Table 3). There were no fungi detected based on the mNGS results for specimens obtained from three patients (patient nos. 91, 101, and 105); nevertheless, the presence of fungi was confirmed in the pathology or culture results. Both mNGS (BALF) and traditional detection methods were positive for pulmonary fungal infections in 19 patients. The pathology of the lung biopsy for 11 patients revealed fungal hyphae. Among all fungal cultures, the fungal culture results for six patients suggested the growth of mold. Of the 10 positive results using BALF from the GM test, six were false positives.

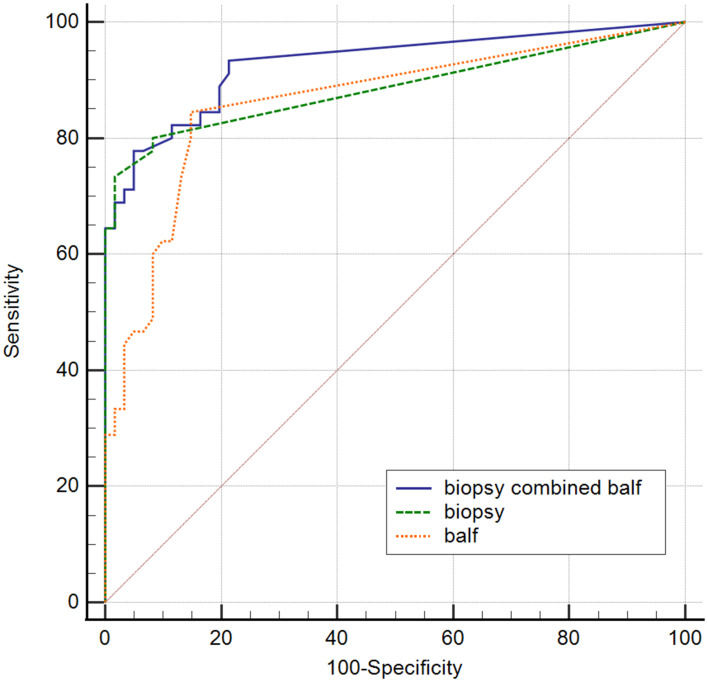

Lung Biopsy and BALF for mNGS

ROC analysis of biopsy-mNGS and BALF-mNGS for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections yielded an AUC of 0.8663 (95% CI, 0.8122–0.9605) and 0.8632 (95% CI, 0.7879–0.9385), respectively (Table 4). Additionally, ROC analysis of mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections yielded an AUC of 0.929 (95% CI, 0.862–0.970) (Table 4). When the threshold was greater than 0.3022, the sensitivity and specificity of mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) were 77.8% (95% CI, 62.9–88.8%) and 95.1% (95% CI, 86.3–99%), respectively. Pairwise ROC curves are shown in Figure 2 and Table 5. The difference in AUC of the two mNGS was only 0.0231 (P=0.5748). The difference in the AUC between mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) and lung biopsy-mNGS was 0.0423 (P=0.0509). Finally, the difference in AUC between mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) and BALF-mNGS was 0.0654 (P=0.018).

Table 4.

Comparison of the ROC for mNGS and the Conventional Tests

| Area Under Curve | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsy combined balf | 0.929 | 0.862–0.970 | P<0.0001 |

| Biopsy | 0.8663 | 0.8122–0.9605 | P<0.0001 |

| Balf | 0.8632 | 0.7879–0.9385 | P<0.0001 |

Figure 2.

Pairwise comparison of the ROC curves.

Abbreviation: ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Table 5.

Comparison of the Difference in the AUC

| Difference Between Areas | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Biopsy combined balf~ biopsy | 0.0423 | 0.0509 |

| Biopsy combined balf ~ balf | 0.0654 | 0.018 |

| Biopsy ~ balf | 0.0231 | 0.5748 |

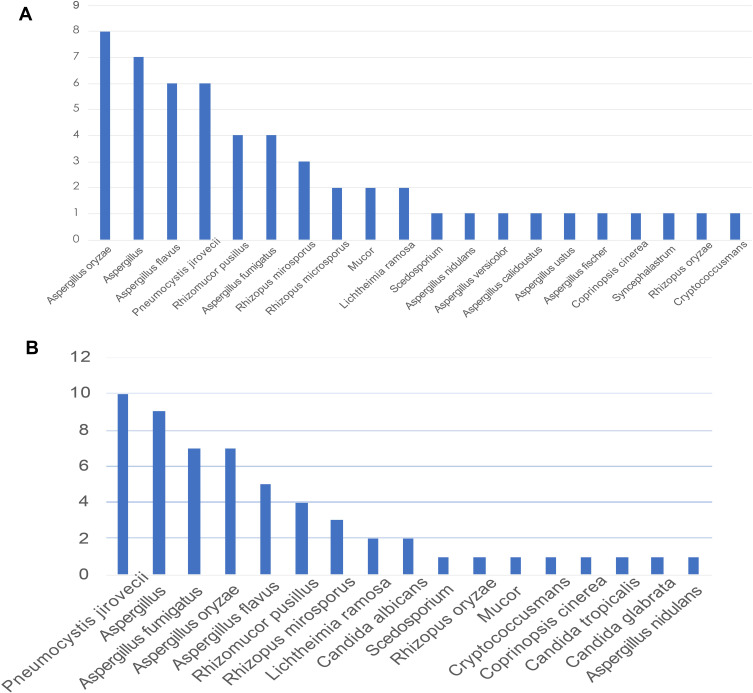

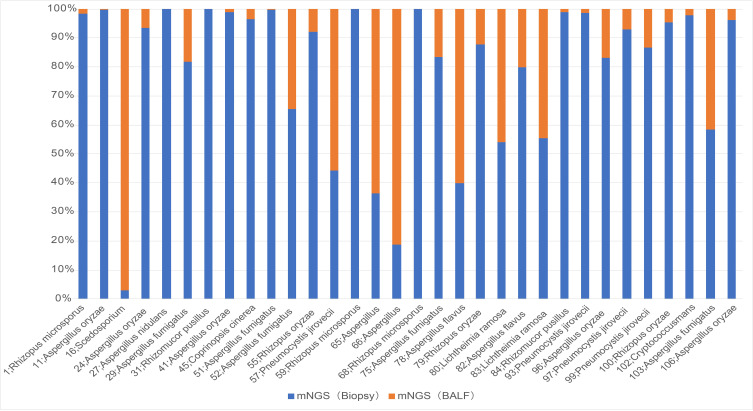

The mNGS provided specific sequencing reads of all microorganisms and valid data that can be detected in the sample. Based on the definition for the pathogens responsible for fungal infections, in combination with the patient’s clinical data to exclude some fungi considered for colonization, this study detected pulmonary fungal infections caused by Rhizopus microsporus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus fumigatus, Rhizomucor pusillus, and Pneumocystis jirovecii. In lung biopsy-mNGS, most of the fungi detected were Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus flavus, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Rhizomucor pusillus, and Aspergillus fumigatus (Figure 3A). In mNGS (BALF), most of the fungi detected were Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus flavus, and Rhizomucor pusillus (Figure 3B). The sequencing reads for fungi produced by each sample ranged from 2 to 522,197.

Figure 3.

(A) Fungi detected using lung biopsy-mNGS. (B) Fungi detected using BALF-mNGS.

Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing.

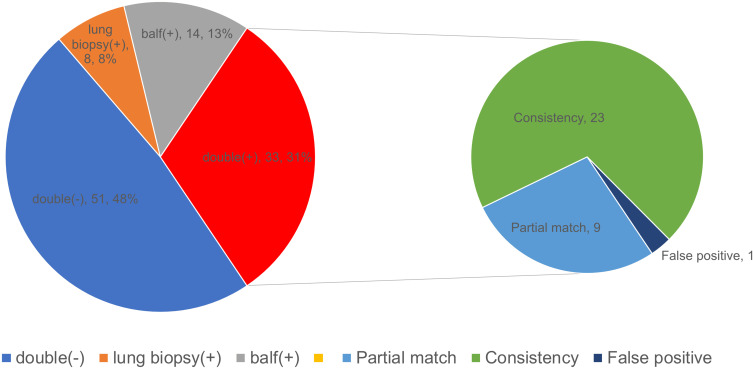

The lung biopsy and BALF results for mNGS were positive for the diagnosis of lung fungal infection in 33 cases. The lung biopsy and BALF from patient no. 54 were used for mNGS to detect Aspergillus and Mycobacterium; however, the final clinical diagnosis was tuberculosis. Both tests were negative for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infection in 51 patients. Eight cases were positive for pulmonary fungal infections using mNGS (biopsy) only, and 14 cases were positive for pulmonary fungal infections using mNGS (BALF) only. In 14 cases, we found that Pneumocystis jiroveci was detected by mNGS (BALF) in patient no. 58; however, the final diagnosis was cryptococcal infection. Among the 32 patients whose final diagnoses were pulmonary fungal infections and mNGS results were positive, 23 (71.88%) cases of consistency between the two detected fungi and nine (28.13%) cases of a partial match were identified (Figure 4). With respect to the partially matched results, the mNGS results of the two specimens did not appear to be completely different; nevertheless, they were partially contained.

Figure 4.

Consistency of the two specimens for mNGS in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections. The pie chart shows the positive distribution of 106 cases investigated for pulmonary fungal infections using lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS. Among the patients whose mNGS results matched for both specimens, the mNGS results of nine patients showed partial matches, 24 patients showed complete matches, but 54 patients had false-positive results.

Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing.

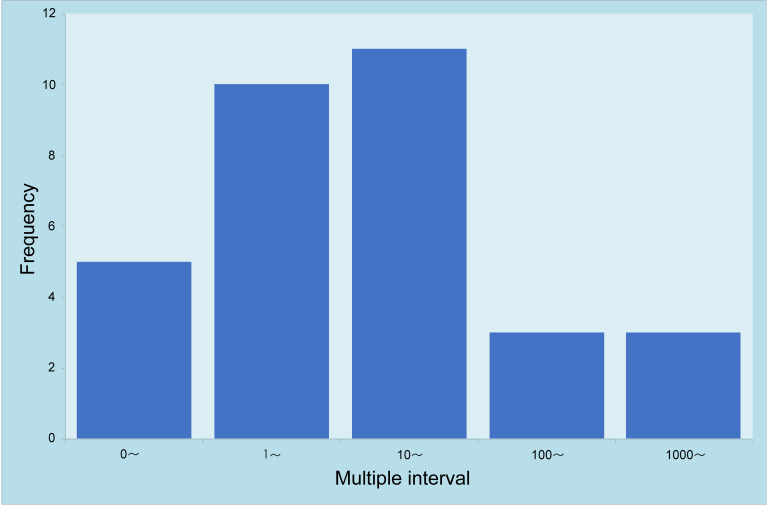

Among 45 patients with a final diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infection, the results from lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS were positive in 32 (75%) patients (Table 6). When multiple types of fungi were detected by mNGS for the two specimens, the fungi with the largest reads were recorded and compared. Among 32 patients with positive mNGS results for both specimens, 27 (84.38%) had more reads of fungi detected by lung biopsy-mNGS than by BALF-mNGS (Figures 5 and 6). In 17 (53.13%) patients, fungal reads detected by lung biopsy-mNGS were more than 10 times greater than those by BALF-mNGS. In 10 patients, the fungal reads detected by lung biopsy-mNGS were between 1 and 10 times greater than those detected by BALF-mNGS. In patient no. 16, the fungal reads detected by BALF-mNGS were significantly greater than those by lung biopsy-mNGS. The fungal reads detected by BALF-mNGS were approximately the same as those by lung biopsy in five patients.

Table 6.

Results of the 32 Patients with Matching mNGS Results

| Patient ID | mNGS (Biopsy, Fungus Detected) | mNGS (Balf, Fungus Detected) | Final Clinical Diagnosis | mNGS (Biopsy) /mNGS (BAL) | Matching Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rhizopus microsporus (1337) Aspergillus oryzae (3) |

Rhizopus microsporus (23) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 58 | Partial match |

| 11 | Aspergillus oryzae (1257) Aspergillus flavus (1146) |

Aspergillus oryzae (4) Aspergillus flavus (1) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 314 | Complete match |

| 16 | Scedosporium (4) | Scedosporium (127) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 0.03 | Complete match |

| 24 | Aspergillus oryzae (155) Aspergillus flavus (102) |

Aspergillus oryzae (11) Aspergillus flavus (6) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 14 | Complete match |

| 27 | Aspergillus nidulans (279,595) Rhizomucor pusillus (3861) Aspergillus versicolor (183) Aspergillus calidoustus (175) Aspergillus ustus (137) |

Aspergillus nidulans (234) Rhizomucor pusillus (6) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 1195 | Partial match |

| 29 | Aspergillus fumigatus (922) Aspergillus fischer (5) |

Aspergillus fumigatus (207) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 4 | Partial match |

| 31 | Rhizomucor pusillus (5320) | Rhizomucor pusillus (2) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 2660 | Complete match |

| 41 | Aspergillus oryzae (863) Aspergillus flavus (207) | Aspergillus oryzae (9) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 96 | Partial match |

| 45 | Coprinopsis cinerea (1380) | Coprinopsis cinerea (49) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 28 | Complete match |

| 51 | Aspergillus fumigatus (41,388) | Aspergillus fumigatus (74) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 559 | Complete match |

| 52 | Pneumocystis jirovecii (12,496) | Pneumocystis jirovecii (6566) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 2 | Complete match |

| 55 | Aspergillus oryzae (46) | Aspergillus oryzae (4) Aspergillus (5) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 12 | Partial match |

| 57 | Pneumocystis jirovecii (360) | Pneumocystis jirovecii (452) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 0.8 | Complete match |

| 59 | Rhizopus microsporus (522,197) Mucor (5755) | Rhizopus microsporus (159) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 3284 | Partial match |

| 65 | Aspergillus (4) | Aspergillus (7) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 0.6 | Complete match |

| 66 | Aspergillus (3) | Aspergillus flavus (13) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 0.2 | Complete match |

| 68 | Rhizopus microsporus (299,937) Mucor (8925) Syncephalastrum (21) |

Rhizopus microsporus (352) Mucor (8) Aspergillus (5) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 852 | Partial match |

| 75 | Aspergillus fumigatus (5938) | Aspergillus fumigatus (1178) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 5 | Complete match |

| 78 | Aspergillus flavus (2) | Aspergillus flavus (3) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 0.7 | Complete match |

| 79 | Aspergillus oryzae (150) | Aspergillus oryzae (21) Aspergillus (32) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 7 | Partial match |

| 80 | Lichtheimia ramosa (196) Rhizomucor pusillus (2) |

Lichtheimia ramosa (166) Rhizomucor pusillus (39) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 1.2 | Complete match |

| 82 | Aspergillus flavus (488) | Aspergillus (123) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 4 | Complete match |

| 83 | Lichtheimia ramosa (186) | Lichtheimia ramosa (149) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 1.2 | Complete match |

| 84 | Rhizomucor pusillus (880) | Rhizomucor pusillus (9) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 98 | Complete match |

| 93 | Pneumocystis jirovecii (321) | Pneumocystis jirovecii (4) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 80.2 | Complete match |

| 96 | Aspergillus oryzae (1618) Aspergillus flavus (1344) |

Aspergillus oryzae (330) Aspergillus flavus (266) |

Pulmonary fungal infections | 4.9 | Complete match |

| 97 | Pneumocystis jirovecii (161,687) | Pneumocystis jirovecii (12,504) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 12.9 | Complete match |

| 99 | Pneumocystis jirovecii (14,006) | Pneumocystis jirovecii (2160) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 6.5 | Complete match |

| 100 | Rhizopus oryzae (42) | Rhizopus oryzae (2) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 21 | Complete match |

| 102 | Cryptococcusmans (557) | Cryptococcusmans (12) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 46.4 | Complete match |

| 103 | Aspergillus fumigatus (28) | Aspergillus fumigatus (20) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 1.4 | Complete match |

| 106 | Aspergillus oryzae (1182) | Aspergillus oryzae (48) Pneumocystis jirovecii (6) | Pulmonary fungal infections | 24.6 | Partial match |

Abbreviation: mNGS/mNGS (BALF), mNGS (Biopsy) most detected fungal reads/mNGS (BAL) most detected fungal reads.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the fungal reads detected by lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS. Multiple interval: mNGS (Biopsy) most detected fungal reads/mNGS (BAL) most detected fungal reads.

Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the fungal reads detected by mNGS with matching results from both specimens in 32 patients.

Abbreviation: mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing.

The information from the 22 patients with inconsistent mNGS results is shown in Table 7. Among the eight and 13 cases with positive lung biopsy-mNGS and positive BALF-mNGS, four and five cases were eventually diagnosed with pulmonary fungal infections, respectively. Among the above mentioned 22 patients, 12 patients had false-positive mNGS results. Only four and eight cases had positive lung biopsy-mNGS and BALF-mNGS results, respectively. Among the false positive cases, Aspergillus, Pneumocystis jejuni, and Candida albicans were most frequently detected, and in 10 (83.33%) patients, the mNGS reads were less than 20. In patients with false positive results, there was a greater frequency of BALF-mNGS cases than lung biopsy-mNGS; however, this difference was not significant (P>0.05).

Table 7.

Sequencing Results for 22 Patients with Inconsistent Lung Biopsy-mNGS and BALF-mNGS

| Patient ID | mNGS (Biopsy, Fungus Detected) | mNGS (BALF, Fungus Detected) | Final Clinical Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Negative | Candida albicans (96) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 14 | Negative | Aspergillus fumigatus (201) | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 26 | Rhizopus microsporus (476) | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 30 | Rhizopus microsporus (3) | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 35 | Aspergillus (3) | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 42 | Pneumocystis jirovecii (13) | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 46 | Aspergillus (5) | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 48 | Negative | Pneumocystis jirovecii (7) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 58 | Negative | Pneumocystis jirovecii (2) | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 62 | Negative | Aspergillus (4) | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 64 | Negative | Candida albicans (13) Aspergillus (5) |

Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 67 | Negative | Aspergillus (3) | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 71 | Aspergillus (3) | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 73 | Negative | Pneumocystis jirovecii (20) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 76 | Aspergillus (4) | Negative | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 81 | Negative | Candida tropicalis (6) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 87 | Negative | Aspergillus (3) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 88 | Aspergillus (3) | Negative | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 89 | Negative | Candida glabrata (146) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 94 | Negative | Aspergillus fumigatus (4) | Pulmonary fungal infection |

| 95 | Negative | Pneumocystis jirovecii (15) | Exclude pulmonary fungal infection |

| 104 | Negative | Aspergillus fumigatus (9) | Pulmonary fungal infection |

Complications in Bronchoscopy

Among the 106 patients included in this study, lung biopsy and BALF were performed at the same time. During transbronchial lung biopsy, a small amount of bleeding was observed under bronchoscopy in eight patients. After instilling hemocoagulase was injected into the bleeding bronchus through the bronchoscope, no active bleeding was observed under the bronchoscope, and the patient’s safety was not threatened. Among the 106 patients who underwent bronchoscopy, none experienced any complications, including fatal hemoptysis, pneumothorax, arrhythmia, and death.

Discussion

Among high-risk groups of patients with immunosuppression, empirical antifungal therapy is becoming increasingly common, which makes the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections more difficult.19 mNGS has been widely used in infectious diseases, but there is a lack of evidence regarding its use in pulmonary fungal infections. Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap and compare the difference between lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS. A previous study reported that mNGS was better than cultures in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections (OR, 4.0 [95% CI, 1.6–10.3], P<0.01).9 In the current study, the specificity of conventional tests did not differ compared to mNGS (conventional tests vs biopsy-mNGS: 88.52% vs 91.8%, P>0.05; conventional tests vs BALF-mNGS: 88.52% vs 85.25%, P>0.05), but the sensitivity of mNGS significantly differed (conventional tests vs biopsy-mNGS: 44.44% vs 80.00%, P<0.05; conventional test vs BALF-mNGS: 44.44% vs 84.44%, P<0.05). The PPV and NPV of conventional tests were 74.07% (95% CI, 53.41–88.13%) and 68.35% (95% CI, 56.80–78.11%), respectively. Since patients with immunodeficiencies were treated with antifungal therapy before the test, the positivity rate of the conventional tests was very low. Compared with the conventional tests, it has been previously reported that mNGS is less affected by antibiotic exposure before detection,9 and that mNGS can detect corresponding pathogens, which is beneficial for targeted treatment.

Reviewing the relevant literature, there are many studies on single lung biopsy or BALF for mNGS in pulmonary infections,10,12 but few studies have evaluated simultaneous mNGS using lung biopsy and BALF specimens to diagnose pulmonary fungal infections. In this study involving 106 patients with suspected pulmonary fungal infection, mNGS detected fungi in the lung biopsy and/or BALF of 55 patients. The sensitivity of lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS in diagnosing pulmonary fungal infections was 80.00% (95% CI, 64.95–89.91%) and 84.44% (95% CI, 69.94–93.01%), whereas their specificity was 91.8% (95% CI, 81.17–96.94%) and 85.25% (95% CI, 73.32–92.62%), respectively; however, these values did not show significant difference (P>0.05). The smaller difference between the two samples in terms of sensitivity might be explained by the fungal infection method (filamentous fungi spread on the surface of lung tissue, and it is often difficult to wash pathogens off using lavage) and the scope of the alveolar lavage (bronchoalveolar lavage involves more lobe segments and more distant sub-segment bronchi). The positivity rate of lung biopsy-mNGS mainly depends on the location of the lesion, such as whether the lesion is connected to the bronchus or close to the surrounding area. In this study, with the assistance of virtual navigation and ROSE, the sensitivity of mNGS (lung biopsy and BALF) was relatively high. ROC analysis of lung biopsy-mNGS for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections yielded an AUC of 0.8663 (95% CI, 0.8122–0.9605). ROC analysis of BALF-mNGS for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections yielded an AUC of 0.8632 (95% CI, 0.7879–0.9385). The difference in the AUC of the two samples evaluated using mNGS was only 0.0.231 (P=0.5748). These findings highlight that mNGS (regardless of whether the test specimen was a lung biopsy or BALF) is a better detection method for the diagnosis of pulmonary fungal infections. The difference in the AUC between the mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) and the mNGS (lung BALF) was 0.0654 (P=0.018). Thus, we found that mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) had a better diagnostic value than BALF-mNGS. The difference in the AUC between the mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) and the mNGS (lung biopsy) was 0.0423 (P=0.0509). Thus, the mNGS (combination of biopsy and BALF) was not better than the lung biopsy-mNGS, possibly because the sample size was not large enough to show a significant difference.

The study detected fungal infections of the lungs caused by Rhizopus microsporus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus fumigatus, Rhizomucor pusillus, and Pneumocystis jirovecii. These findings are similar to those reported by Li et al,1 but the current study only identified one case of cryptococcal infection. In this study, among 32 patients whose lung biopsy and BALF were both positive on the basis of mNGS and were thus diagnosed with pulmonary fungal infection, 23 (71.88%) cases of a complete match between the two detected fungi and nine (28.13%) cases of a partial match were identified. The results from the two different specimens did not completely differ; however, the mNGS results matched completely or contained each other. The findings of this study indicated that lung biopsy and BALF for mNGS showed specific consistency in fungal detection. Out of 32 patients with positive mNGS results for both specimens, 27 (84.38%) had more reads of fungi detected by lung biopsy-mNGS than by BALF-mNGS. Reads of fungi detected by lung biopsy-mNGS were more than 10 times greater than those detected by BALF-mNGS in 17 (53.13%) patients. These findings suggest that the reads of fungi detected by BALF-mNGS were generally small, which may be related to the fungal infection method (filamentous fungi spread on the surface of lung tissue, and it is often difficult to wash pathogens off using lavage). When lung tissues are obtained from the target site of the lesion and used for mNGS, the fungal reads can be detected several times higher than that with BALF.

In this study, 22 patients had inconsistent results from lung biopsy-mNGS and BALF-mNGS. The mNGS results were positive for lung biopsy and negative for BALF in eight patients; this might be attributed to the fact that the fungi are filamentous and spread on the tissue surface, which is difficult to wash down using bronchoalveolar lavage. Furthermore, the mNGS results were negative for lung biopsy and positive for BALF in 14 patients, which might be explained by the fact that the bronchi are not connected to the lesion site or the lesion tissue is not obtained; however, the alveolar lavage involves a wider range. Since the lavage fluid involves more leaf segments and a more distant sub-segment bronchus, which involves a wider range, we found that BALF-mNGS had more false positive results than lung biopsy. However, this difference was not significant (P>0.05), which may be a result of the small sample size.

This study was subject to several limitations which merit mentioning here. To date, the mNGS test used in this study has been delivered to commercial laboratories, but not to the hospital’s microbiology laboratory. This may increase the turnaround time and reduce the storage capacity, thus reducing the sensitivity of the test. Additionally, the sample size included in this study was not large, which caused a slight deviation in the ROC curve drawn.

Conclusion

This study showed that mNGS has obvious advantages when compared with conventional tests in pulmonary fungal infection. Additionally, there is no difference in diagnostic performance between lung-biopsy-mNGS and BALF-mNGS. However, lung-mNGS can generally detect several times the fungal reads when compared to BALF-mNGS. Lung biopsy or BALF for mNGS is recommended for patients with suspected pulmonary fungal infection to identify the pathogen as early as possible. The combination of biopsy and BALF for mNGS may be considered when higher diagnostic efficacy is required.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Li Z, Lu G, Meng G. Pathogenic fungal infection in the lung. Front Immunol. 2019;10. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6616198/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvanitis M, Mylonakis E. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: recent developments and ongoing challenges. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45(6):646–652. doi: 10.1111/eci.12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perfect JR, Cox GM, Lee JY, et al. The impact of culture isolation of Aspergillus species: a hospital‐based survey of aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(11):1824–1833. doi: 10.1086/323900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hage CA, Carmona EM, Epelbaum O, et al. Microbiological laboratory testing in the diagnosis of fungal infections in pulmonary and critical care practice. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(5):535–550. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1185ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surmont I, Stockman W. Gluconate-containing intravenous solutions: another cause of false-positive galactomannan assay reactivity. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(4):1373. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02373-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hage CA, Reynolds JM, Durkin M, Wheat LJ, Knox KS. Plasmalyte as a cause of false-positive results for Aspergillus galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(2):676–677. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01940-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Racil Z, Kocmanova I, Lengerova M, Winterova J, Mayer J. Intravenous PLASMA-LYTE as a major cause of false-positive results of platelia aspergillus test for galactomannan detection in serum. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):3141–3142. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00974-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu W, Miller S, Chiu CY. Clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing for pathogen detection. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2019;14(1):319–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miao Q, Ma Y, Wang Q, et al. Microbiological diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing when applied to clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(suppl_2):S231–S240. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Sun B, Tang X, et al. Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for bronchoalveolar lavage diagnostics in critically ill patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 2020;39(2):369–374. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03734-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H-C, Ai J-W, Cui P, et al. Incremental value of metagenomic next generation sequencing for the diagnosis of suspected focal infection in adults. J Infect. 2019;79(5):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Gao H, Meng H, et al. Detection of pulmonary infectious pathogens from lung biopsy tissues by metagenomic next-generation sequencing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:205. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Han Y, Feng J. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing for mixed pulmonary infection diagnosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):252. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-1022-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, et al. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(9):1004–1014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0320ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, Jiang E, Yang D, et al. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing versus traditional pathogen detection in the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary infectious lesions. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:567–576. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S235182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Xu H, Li Z, et al. Pathogens in patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;81:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European organization for research and treatment of cancer and the mycoses study group education and research consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li N, Cai Q, Miao Q, Song Z, Fang Y, Hu B. High‐throughput metagenomics for identification of pathogens in the clinical settings. Small Methods. 2021;5(1):2000792. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202000792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]