Abstract

Background

Attenuation of transforming growth factor β by blocking angiotensin II has been shown to reduce emphysema in a murine model. General population studies have demonstrated that the use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) is associated with reduction of emphysema progression in former smokers and that the use of ACEis is associated with reduction of FEV1 progression in current smokers.

Research Question

Is use of ACEi and ARB associated with less progression of emphysema and FEV1 decline among individuals with COPD or baseline emphysema?

Methods

Former and current smokers from the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD Study who attended baseline and 5-year follow-up visits, did not change smoking status, and underwent chest CT imaging were included. Adjusted linear mixed models were used to evaluate progression of adjusted lung density (ALD), percent emphysema (%total lung volume <–950 Hounsfield units [HU]), 15th percentile of the attenuation histogram (attenuation [in HU] below which 15% of voxels are situated plus 1,000 HU), and lung function decline over 5 years between ACEi and ARB users and nonusers in those with spirometry-confirmed COPD, as well as all participants and those with baseline emphysema. Effect modification by smoking status also was investigated.

Results

Over 5 years of follow-up, compared with nonusers, ACEi and ARB users with COPD showed slower ALD progression (adjusted mean difference [aMD], 1.6; 95% CI, 0.34-2.9). Slowed lung function decline was not observed based on phase 1 medication (aMD of FEV1 % predicted, 0.83; 95% CI, –0.62 to 2.3), but was when analysis was limited to consistent ACEi and ARB users (aMD of FEV1 % predicted, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.14-3.6). No effect modification by smoking status was found for radiographic outcomes, and the lung function effect was more pronounced in former smokers. Results were similar among participants with baseline emphysema.

Interpretation

Among participants with spirometry-confirmed COPD or baseline emphysema, ACEi and ARB use was associated with slower progression of emphysema and lung function decline.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.gov; No.: NCT00608764; URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

Key Words: angiotensin II, COPD, emphysema progression

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ALD, adjusted lung density; aMD, adjusted mean difference; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; COPDGene, Genetic Epidemiology of COPD; HU, Hounsfield unit; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; Perc15, 15th percentile of the attenuation histogram; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; TLV, total lung volume

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 1160

COPD is a leading cause of death worldwide1 and is characterized by airflow obstruction and pulmonary emphysema or airspace enlargement with destruction of alveolar walls.2 The degree of radiographic emphysema on CT imaging predicts morbidity and mortality, independent of lung function, among individuals with COPD3,4 and also is associated with incident airflow obstruction,5 increased dyspnea,6 and mortality among individuals without COPD.7

Disturbances in transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling have been identified as a contributing factor to increased extracellular matrix observed in the distal airways of patients with severe COPD that may compromise repair in the airspace compartment, leading to histologic emphysema.8,9 Furthermore, TGF-β2 genetic variants and TGF-β-related loci have been implicated in emphysema, lung function, and COPD susceptibility.10,11 These observations have led to therapeutic interest in TGF-β antagonism with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs).12,13

Angiotensin-receptor blockade has been demonstrated to improve histologic changes in a murine model of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema.14 In a human pilot study, ARB treatment was associated with a trend toward improvement in emphysema in those with baseline emphysema after 12 months of therapy.15 Data from the general population of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Lung Study showed that use of ACEis or ARBs was associated with slower progression of emphysema, most pronounced in former smokers.16 Data from the Lovelace Smokers Cohort, a general population study of current smokers, found that ACEi use was associated with less rapid decline in FEV1.17 Whether ACEi or ARB use is associated with attenuation of emphysema or lung function progression in those with established COPD is unclear. Furthermore, whether any association in those with established disease is affected by smoking status also is undetermined. We sought to assess the association of ACEi and ARB use with radiographic emphysema and lung function progression in the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Study among participants with spirometry-confirmed COPD and, separately, those with radiographic emphysema and all participants regardless of COPD status or baseline emphysema.

Methods

COPDGene Cohort

The COPDGene Study is a multicenter prospective, observational study that recruited > 10,000 participants who self-identified as non-Hispanic White or Black. Individuals 45 to 80 years of age with a ≥ 10-pack-year cigarette smoking history with and without COPD were included.18 The COPDGene Study was approved by the institutional review board at each site, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT00608764).

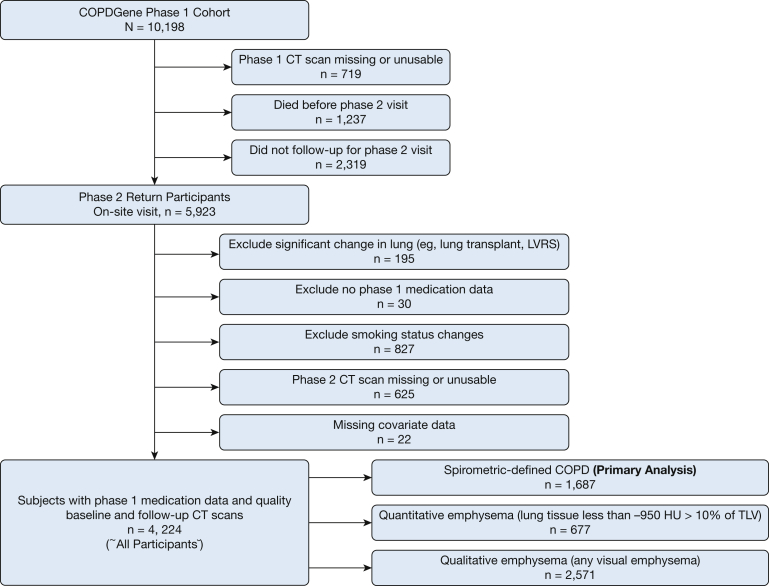

This study included participants enrolled in phase 1 (baseline) from 2008 through 2011 with complete medication data and completed phase 2 (5-year follow-up) visits, conducted between 2013 and 2016. Participants were excluded if they did not have quality CT scan data at either visit or if they reported a change in smoking status between phase 1 and phase 2 visits, because smoking cessation is associated with a decrease in lung attenuation,19 or if a significant change in lung volume occurred (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing inclusion and exclusion criteria. COPDGene = Genetic Epidemiology of COPD; TLV = total lung volume; LVRS = lung volume reduction surgery.

ACEi and ARB Assessment

Medications were assessed at phase 1 and phase 2 visits by self-report. Medications were grouped as ACEi and ARB using standard pharmacopeia (e-Table 1). Participants who had the same ACEi or ARB status at both phases (ie, did not start or stop ACEi or ARB therapy during the follow-up period) hereafter are referred to as consistent users. Participants who alternated between an ACEi or ARB use but were still taking a medication within either class also were defined as consistent users.

Radiographic Outcomes of Interest

Noncontrast axial inspiratory and expiratory CT scans were obtained during both phases using a standardized protocol described in e-Appendix 1.18 The primary outcome is emphysema measured by adjusted lung density (ALD) quantified on inspiratory scans using MESA equations to adjust for total lung volume (TLV).20 We chose ALD as the primary outcome given that it quantifies emphysema more robustly independent of changes in FEV1.21 Secondary outcomes included other emphysema: (1) percentage of TLV less than –950 Hounsfield units (HU; percent emphysema) and (2) based on the 15th percentile of the attenuation histogram (Perc15) method (attenuation [in HU] less than which 15% of voxels are situated plus 1,000 HU) adjusted for difference in TLV between baseline and follow-up scans.21

Pulmonary Function Testing

Spirometry was performed using the EasyOne spirometer (Medical Technologies) in accordance with European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society guidelines.22 COPD was defined as postbronchodilator ratio of FEV1 to FVC of < 70%. Predicted values for FEV1 were calculated using Hankinson equations,23 and change in FEV1 % predicted was investigated as a secondary outcome.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis included individuals with spirometry-confirmed COPD. ACEi and ARB status was defined based on medications being taking during phase 1. Baseline characteristics were compared between ACEi and ARB users and nonusers using the χ2 or Student t tests. Longitudinal analysis was conducted using linear mixed models with an unstructured covariance structure to account for within-participant correlation and random intercepts for clinical site and scanner model. All models were adjusted for baseline age, sex, race, smoking status, BMI (underweight, < 18.5 kg/m2; normal or overweight, 18.5-29.9 kg/m2; and obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2), CT scanner model, systolic and diastolic BPs, use of aspirin or statin,24,25 self-reported history of diabetes, congestive heart failure, and atherosclerotic disease (coronary artery disease, heart attack, coronary artery bypass surgery, or stroke). In longitudinal models, BMI, CT scanner model, respiratory medication use, and systolic and diastolic BP were included as time-varying covariates and an interaction between ACEi and ARB status and time (study phase) was included to evaluate change of each outcome of interest. Models assessing FEV1 % predicted as an outcome did not include adjustment for CT scanner model. These analyses also were performed in all participants meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria regardless of COPD status and in subsets of participants with radiographic emphysema defined as lung tissue less than –950 HU > 10% of TLV (quantitative emphysema) or presence of any emphysema by visual analysis (qualitative emphysema).26 Among all participant analyses, a multiplicative interaction between COPD status, ACEi and ARB use, and time (study phase) was used to assess effect modification by COPD status. In the COPD participant analysis, a multiplicative interaction between Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage, ACEi and ARB use, and time (study phase) was used to assess effect modification by COPD severity, defined by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage. Effect modification by smoking status was evaluated by including a multiplicative interaction between smoking status, ACEi and ARB use, and time (study phase). Models that included all participants were adjusted additionally for dichotomous baseline COPD status.

Secondary analysis was conducted including only consistent users. We also compared ACEi users with ACEi and ARB nonusers and ARB users with ACEi and ARB nonusers to explore whether differences existed between ACEi and ARB users. Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analyses that added β-blocker and calcium-channel blocker use individually as covariates along with their interaction with time to evaluate whether the observed effect was the result of antihypertensive therapy. Finally, to account for baseline differences among ACEi and ARB users compared with nonusers and residual confounding, sensitivity analyses with propensity score matching was conducted (described in e-Appendix 1) and weighing ACEi and ARB assignment by the inverse of inverse of the propensity score.27, 28, 29, 30 P < .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute).

Results

Of the initial 10,198 COPDGene participants, 5,923 had a quality phase 1 CT scan and returned for a phase 2 visit (719 did not have a quality phase 1 CT scan, 1,237 died before phase 2, and 2,319 did not have phase 2 follow-up). An additional 1,699 met a prespecified exclusion criteria; thus, 4,224 participants met all inclusion criteria (Fig 1). Of these participants (henceforth, all participants), 1,687 (40%) had spirometry-defined COPD, 677 (16%) had quantitatively defined emphysema, and 2,571 (61%) had qualitative emphysema.

Approximately one-quarter of participants (n = 472 [28%]) reported ACEi or ARB use at baseline (Table 1). ACEi and ARB users were older and were more likely to be men and former smokers, but had higher pack-year smoking histories compared with nonusers. The ACEi and ARB users also showed a higher BMI, prevalence of cardiac comorbidities and diabetes, and use of aspirin and statins. Three-quarters of these participants (n = 1,307) showed consistent ACEi or ARB status between visits, of which 325 were consistent ACEi or ARB users. Participants who died before the second visit (n = 881) or did not complete the second visit (n = 1,130) had more severe COPD and emphysema and were more likely to be current smokers with more substantial smoking history, to be underweight, and to be users of respiratory medications; however, they showed no difference in ACEi or ARB use (e-Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | No ACE or ARB Use (n = 1,215) | ACE or ARB Use (n = 472) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.2 ± 8.4 | 65.7 ± 7.4 | < .0001 |

| Female sex | 588 (48.4) | 192 (40.7) | .004 |

| Black | 243 (20) | 84 (17.8) | .3 |

| FEV1 % predicted | 64.3 ± 21 | 62.7 ± 19.8 | .2 |

| GOLD stage | ... | ... | .0001 |

| 1 (FEV1 ≥ 80%, FEV1 to FVC ratio, < 0.7) | 294 (24.2) | 96 (20.3) | ... |

| 2 (50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%, FEV1 to FVC ratio, < 0.7) | 584 (48.1) | 237 (50.2) | ... |

| 3 (30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%, FEV1 to FVC ratio, < 0.7) | 268 (22.1) | 119 (25.2) | ... |

| 4 (FEV1 < 30%, FEV1 to FVC ratio, 0.7) | 69 (5.7) | 20 (4.2) | ... |

| Percent emphysema < –950 HU | 10.1 ± 10.7 | 9.7 ± 8.8 | .47 |

| Adjusted lung density, g/L | 74.0 ± 23.7 | 74.2 ± 25.3 | .9 |

| Perc15, HU | 68.3 ± 24.8 | 68.4 ± 27.1 | .9 |

| 6MWT, feet | 1,381.5 ± 364.2 | 1,309.5 ± 348.6 | .0003 |

| SGRQ total score | 29.4 ± 21.5 | 31 ± 20.9 | .2 |

| No. of exacerbations in the last year | 0.48 ± 1 | 0.52 ± 1 | .4 |

| Current smoker | 489 (40.3) | 118 (25) | < .0001 |

| Pack-years smoked | 48.3 ± 25.1 | 52.9 ± 26.4 | .001 |

| Respiratory medication use | 671 (55.2) | 291 (61.7) | .02 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 432 (36) | 185 (39.8) | .2 |

| BMI | 27.7 ± 5.6 | 29.7 ± 5.8 | < .0001 |

| BMI category | ... | ... | < .0001 |

| Underweight | 21 (1.7) | 2 (0.4) | ... |

| Normal or overweight | 826 (68) | 275 (58.3) | ... |

| Obese | 368 (30.3) | 195 (41.3) | ... |

| Congestive heart failure | 28 (2.3) | 22 (4.7) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 79 (6.5) | 122 (25.9) | < .0001 |

| High BP | 378 (31.1) | 420 (89) | < .0001 |

| High cholesterol | 442 (36.4) | 284 (60.2) | < .0001 |

| Atherosclerotic disease | 121 (10) | 117 (24.8) | < .0001 |

| History of heart attack | 67 (5.5) | 62 (13.1) | < .0001 |

| History of stroke | 36 (3) | 19 (4) | .3 |

| History of coronary artery bypass graft | 23 (1.9) | 35 (7.4) | < .0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 69 (5.7) | 88 (18.6) | < .0001 |

| BP, mm Hg | ... | ... | ... |

| Systolic | 129.2 ± 16.4 | 130.7 ± 17.3 | .1 |

| Diastolic | 76.2 ± 10.5 | 74.7 ± 10.9 | .01 |

| Oral corticosteroid | 32 (2.7) | 12 (2.6) | .9 |

| Aspirin | 197 (16.2) | 181 (38.4) | < .0001 |

| Statin | 262 (21.6) | 253 (53.6) | < .0001 |

| Calcium-channel blocker | 111 (9.1) | 117 (24.8) | < .0001 |

| β-blocker | 137 (11.3) | 135 (28.6) | < .0001 |

| Same scanner identification at both visits | 576 (47.4) | 223 (47.3) | 1 |

| Same scanner model at both visits | 700 (57.6) | 270 (57.2) | .9 |

Data are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated. ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HU = Hounsfield unit; Perc15 = 15th percentile of the attenuation histogram; SGRQ = St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; 6MWT = 6-min walk test.

Primary Outcome of ALD

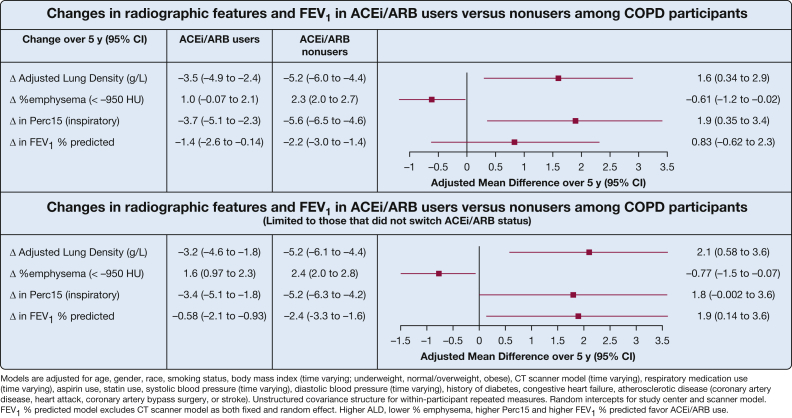

In longitudinal analysis of participants with spirometry-confirmed COPD, baseline ACEi and ARB users showed less worsening of lung density over 5 years (adjusted mean difference [aMD] of ALD, 1.6 g/L; 95% CI, 0.34-2.9 g/L) compared with ACEi and ARB nonusers. When limiting analysis to those with consistent ACEi or ARB status, results were stronger with consistent ACEi or ARB users having a 2.1-g/L slower progression of ALD (95% CI, 0.58-3.6 g/L) (Fig 2). No difference was found between ACEi users (n = 340) and ARB users (n = 132) when evaluated separately (e-Fig 1).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing change in radiographic features and FEV1 in ACEi and ARB users vs nonusers among participants with COPD. ACEi = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; HU = Hounsfield unit; Perc15 = 15th percentile of the attenuation histogram.

For participants with baseline emphysema, results were stronger in those with quantitative emphysema showing an association between baseline ACEi and ARB use and less progression of lung density (aMD, 1.8 [95% CI, 0.17-3.4] in those with quantitative emphysema; aMD, 0.93 [95% CI, –0.06 to 1.9] in those with qualitative emphysema). The results again were more robust when limiting to those whose ACEi or ARB status did not change (e-Table 3). When analyzing all participants meeting inclusion criteria regardless of COPD status or baseline emphysema, ACEi and ARB users showed directionally similar—but not statistically significant—less progression of ALD (aMD, 0.54; 95% CI, –0.22 to 1.3). Results still did not achieve statistical significance when limiting to consistent ACEi and ARB users.

Secondary Emphysema Outcomes

Among participants with COPD, baseline ACEi and ARB use was associated with significantly less progression in percent emphysema (aMD, –0.61; 95% CI, –1.2 to –0.02) and Perc15 (aMD, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.35-3.4), with similar results when limiting analysis to consistent users (Fig 2). No difference was found between ACEi and ARB users when evaluated separately (e-Fig 1).

For participants with baseline emphysema, results of secondary emphysema measures again were stronger in those with quantitative emphysema. When limited to those with the consistent ACEi or ARB status, associations remained stronger in those with quantitative emphysema. Among all participants, similar, but nonstatistical, trends were found of slowing of progression in emphysema and Perc15. Analysis limited to those with consistent ACEi or ARB status demonstrated similar results (e-Table 3).

Secondary Outcome of Lung Function (FEV1 % Predicted)

Among participants with COPD, those reporting baseline ACEi or ARB use showed a trend toward lower loss in lung function (0.83%; 95% CI, –0.62 to 2.3) (Fig 2) compared with those not using ACEis or ARBs at baseline. When limiting to those with consistent ACEi or ARB status, a slower progression of FEV1 % predicted was found that showed a 1.9% lower loss (95% CI, 0.14%-3.6%). When analyzing COPD participants who were ACEi users and ARB users separately, the slowing FEV1 % predicted progression seemed to be more pronounced in ACEi users, but neither was statistically significant (e-Fig 1).

In those with qualitative and quantitative emphysema at baseline, baseline ACEi and ARB users showed a decline in attenuated progression of FEV1 % predicted compared with those not reporting ACEi or ARB use (aMD for FEV1 % predicted, 2.5 less [95% CI, 0.23-4.8] in those with quantitative emphysema and 1.1 less [95% CI, 0.05-2.2] in those with qualitative emphysema). When limited to consistent users, associations were stronger, with consistent ACEi or ARB users showed a 3.6% and 2.2% lower loss in FEV1 % predicted among those with baseline quantitative and qualitative emphysema, respectively. Among all participants, no statistically significant association was found with slowing in FEV1 % predicted (aMD, 0.7% less; 95% CI, –0.09 to 1.6 less) based on phase 1 medication, but a statistically significant association was found when limiting the analysis to consistent users (aMD, 1.2% less; 95% CI, 0.27%-2.2% less).

Effect Modification and Sensitivity Analyses

Among all participants, effect modification by COPD status was statistically significant (P < .05 for interaction) for the primary outcome of ALD, and trends were similar but not statistically significant for secondary emphysema outcomes (e-Table 4). Among participants with COPD, no effect modification was found by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage (e-Table 5). Among participants with COPD, no effect modification was found by smoking status on progression of ALD, percent emphysema, or Perc15 (all P > .05 for interaction). However, the protective association between ACEi or ARB status and lung function decline was stronger among former smokers than current smokers, a trend that was similar, but not statistically significant, when limiting to consistent users (e-Table 6).

The propensity score-matched sensitivity analysis included 405 participant pairs (e-Table 7). An association was found between ACEi or ARB use and slower progression of ALD and Perc15, but results were attenuated for percent emphysema and FEV1 % predicted. Results for the inverse probability of treatment weights analysis was similar to those for the main analysis (e-Table 8). The sensitivity analysis investigating alternative antihypertensive medication revealed that β-blocker and calcium-channel blocker users did not show a change in primary or secondary outcomes when compared with nonusers (e-Table 9).

Discussion

In those with COPD, either confirmed by spirometry or those with quantitative or qualitative emphysema, ACEi and ARB use was associated with slower progression of emphysema, regardless of current or former smoking status. ACEi and ARB use also was associated with attenuated lung function decline, particularly in former smokers. Participants reporting consistent ACEi or ARB use showed more robust signals for slowing emphysema progression and lung function decline. The magnitude of effect of ACEi and ARB use with emphysema and FEV1 % predicted progression was less when analyzing all participants in the COPDGene Study, suggesting that individuals with existing evidence of disease are more likely to benefit from any potential protective effects of ACEi and ARB use.

Although our results suggest that those with existing evidence of disease (airflow obstruction or emphysema) may be more likely to benefit from ACEi or ARB use and association results were less strong when including smokers without evidence of obstructive lung disease, other studies suggest that ACEi and ARB use also may be associated with attenuated emphysema or lung function progression in general population cohorts. A prior study of MESA Lung participants identified ACEi and ARB users among a general population cohort without clinical cardiovascular disease as showing a slower progression of emphysema.16 In the MESA study, the association of ACEi and ARB use was more pronounced in former smokers, but was not statistically significant in current smokers. In our study, we did not find effect modification by smoking status, and the difference in study results may be because our cohort included only participants with heavy smoking histories, or because the association of ACEi and ARB use in those already identified to be susceptible to disease by having baseline airflow obstruction or emphysema may be larger and evident regardless of smoking status. Additionally, a study of smokers without COPD from the Lovelace Smokers Cohort showed that ACEi users demonstrated slower worsening of FEV1 on serial spirometry.17 We observed a similar slowing in all participants that included both former and current smokers and among those with COPD when limiting to those with consistent ACEi and ARB status, with a more pronounced effect in former smokers. No established minimally clinically important difference for FEV1 % predicted exists; however, regulators have noted that a change of 5% to 10% of change from baseline is considered to be clinically important.31 The difference over 5 years did not meet this threshold, but prolonged use may lead to such a change. Similarly, no minimally clinically important difference has been established for ALD, but increased radiographic emphysema has been associated with worse COPD morbidity21,32 and increased mortality.3,4,33 For example, a recent study of COPDGene participants found that a 1-g/L faster decline in lung density per year was associated with an 8% higher all-cause mortality and a 22% higher respiratory mortality.34

Our results add strength to the results of a pilot trial of 106 participants with COPD, randomized to losartan vs placebo for 12 months of therapy, that showed a marginal significant difference between the subgroup of 50 participants with baseline emphysema (β = –2.5%; P = .06) in emphysema progression, which was defined as 5% to 35% of voxels < 950 HU.15 The hypothesized mechanism of our observations is attenuation of TGF-β through reduction of angiotensin II effect on angiotensin II type 1 receptors. The hypothesis that protective benefits are conferred through TGF-β is supported by histologic emphysema improvement in a murine model of emphysema with both TGF-β-specific neutralizing antibody or ARB therapy.14 Studies have demonstrated that angiotensin II stimulates extracellular protein synthesis via TGF-β activation and may lead to a fibroproliferative response.13,35 It also may be related to effects on angiotensin II on the Smad2/3 pathway that, in other cell types, has been shown to occur in a TGF-β-independent mechanism.36 Other mechanisms that may be complementary also are plausible. Improvement in skeletal muscle function has been postulated given that angiotensin II promotes skeletal muscle atrophy37; however, trials thus far of ACEi in COPD have not improved muscle strength, either alone or as an adjunct to pulmonary rehabilitation.38,39 Angiotensin II also generates reactive oxygen species and exerts a direct proinflammatory effect on immune cells, which is proposed to occur through activation of the nuclear factor κ B pathway, rather than TGF-β.40 Finally, attenuating the classical effects of angiotensin II on pulmonary vasculature, for example, vasoconstriction and reduced nitric oxide,41 are less likely to explain an improvement in radiographic emphysema and lung function. This ambiguity is underscored further and amplified by studies assessing ACEi independently or ARB independently or considering them together. Although both abrogate the effects of angiotensin II, they do so in distinct manners, namely, ACEi inhibits conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, whereas ARBs function as an angiotensin II receptor antagonist. Whether the benefits conferred from ARBs are related to preventing deleterious effects through antagonism of angiotensin II type I receptors or protective benefits through increased agonism of angiotensin II type II receptors is unknown.42 We observed comparable benefits of slowing emphysema progression in both the ACEi-only group and ARB-only group; however, the slowing of FEV1 % predicted progression seemed more pronounced in the ACEi-only group. Therefore, it is plausible that the protective mechanism may be through antagonism of angiotensin type 1 receptors. However, further studies are required to elucidate the specific signaling mechanism of angiotensin II and its role in emphysema and COPD.

Limitations of our study merit discussion. Only participants who completed the phase 2 visit were included in our study, which biased our cohort toward a healthier group than those who were lost to follow-up or died before the phase 2 visit. Our medication data did not include dosage, and therefore, we were unable to assess for a dose-response effect that was identified previously in the MESA Lung participants.16 Furthermore, medication was self-reported, and we did not have medication data at both visits for all participants. However, we addressed the durability of our results by repeating analyses on those with phase 1 and phase 2 medication data who did not change ACEi or ARB status. We structured our study to evaluate prevalent users given an unknown start date, and therefore an unknown duration of exposure before study entry. This may be interpreted as a continued benefit; however, given an unknown duration of exposure before phase 1, no definitive conclusions can be drawn. Also a potential for confounding exists by indication for treatment with an ACEi or ARB or residual confounding. However, the strength of our study lies in the comprehensive phenotype data and the ability to investigate subgroups with baseline pulmonary disease and adequate sample size to explore effect modification by smoking status.

Interpretation

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report slower progression of emphysema and FEV1 decline among adults with COPD and those with presence of quantitative and qualitative radiographic emphysema in ACEi and ARB users. Findings from this study support the pursuit of randomized control trials regardless of smoking status to determine potential therapeutic benefit of ACEi and ARB use in patients with emphysema or spirometry-confirmed COPD.

Take-home Points.

Study Question: Is ACEi and ARB use associated with less progression of emphysema and FEV1 decline among individuals with COPD or baseline emphysema?

Results: Over a 5-year follow-up, ACEi and ARB users with COPD showed slower ALD progression (adjusted mean difference [aMD], 1.6; 95% CI, 0.34-2.9). Slowed lung function decline was not observed based on phase 1 medication (aMD of FEV1 percent predicted, 0.83; 95% CI, –0.62 to 2.3), but was when analysis was limited to consistent ACEi and ARB users (aMD of FEV1 percent predicted, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.14-3.6). No effect modification by smoking status was found for radiographic outcomes, and the lung function effect was more pronounced in former smokers. Results were similar among participants with baseline emphysema.

Interpretation: Among participants with spirometry-confirmed COPD or baseline emphysema, ACEi and ARB use was associated with slower progression of emphysema and lung function decline.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: V. T. is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript. V. T., F. R. D., and N. N. H conceived of the presented concept. P. C., M. H. C., K. A. P., and S. A. B. contributed to the study design. D. A. L. and S. M. H. contributed to the radiologic assessments and outcomes. G. L. K. ensured veracity of medication data. V. T., A. F., N. P., and N. N. H. performed biostatistical analysis. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: M. H. C. has received grant support from GSK and Bayer and consulting or speaking fees from Genentech, AstraZeneca, and Illumina. None declared (V. T., A. F., N. P., P. C., K. A. P., S. P. B., D. A. L., S. M. H., G. L. K., F. R. D.).

∗COPDGene Investigators – Core Units:Administrative Center: James D. Crapo, MD (PI); Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD (PI); Barry J. Make, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD. Genetic Analysis Center: Terri Beaty, PhD; Ferdouse Begum, PhD; Peter J. Castaldi, MD, MSc; Michael Cho, MD; Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Adel R. Boueiz, MD; Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Eitan Halper-Stromberg; Lystra P. Hayden, MD, MMSc; Craig P. Hersh, MD, MPH; Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS, MPH; Brian D. Hobbs, MD; John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Nan Laird, PhD; Christoph Lange, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Merry-Lynn McDonald, PhD; Margaret M. Parker, PhD; Dmitry Prokopenko, Ph.D; Dandi Qiao, PhD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Phuwanat Sakornsakolpat, MD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; Emily S. Wan, MD; Sungho Won, PhD. Imaging Center: Juan Pablo Centeno; Jean-Paul Charbonnier, PhD; Harvey O. Coxson, PhD; Craig J. Galban, PhD; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Eric A. Hoffman, Stephen Humphries, PhD; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; Philip F. Judy, PhD; Ella A. Kazerooni, MD; Alex Kluiber; David A. Lynch, MB; Pietro Nardelli, PhD; John D. Newell Jr., MD; Aleena Notary; Andrea Oh, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; James C. Ross, PhD; Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD; Joyce Schroeder, MD; Jered Sieren; Berend C. Stoel, PhD; Juerg Tschirren, PhD; Edwin Van Beek, MD, PhD; Bram van Ginneken, PhD; Eva van Rikxoort, PhD; Gonzalo Vegas Sanchez-Ferrero, PhD; Lucas Veitel; George R. Washko, MD; Carla G. Wilson, MS; PFT QA Center, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, PhD. Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Douglas Everett, PhD; Jim Crooks, PhD; Katherine Pratte, PhD; Matt Strand, PhD; Carla G. Wilson, MS. Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO: John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Gregory Kinney, MPH, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Kendra A. Young, PhD. Mortality Adjudication Core: Surya P. Bhatt, MD; Jessica Bon, MD; Alejandro A. Diaz, MD, MPH; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Barry Make, MD; Susan Murray, ScD; Elizabeth Regan, MD; Xavier Soler, MD; Carla G. Wilson, MS. Biomarker Core: Russell P. Bowler, MD, PhD; Katerina Kechris, PhD; Farnoush Banaei-Kashani, Ph.D. COPDGene® Investigators – Clinical Centers: Ann Arbor VA: Jeffrey L. Curtis, MD; Perry G. Pernicano, MD. Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, MD, MS; Mustafa Atik, MD; Aladin Boriek, PhD; Kalpatha Guntupalli, MD; Elizabeth Guy, MD; Amit Parulekar, MD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Alejandro A. Diaz, MD, MPH; Lystra P. Hayden, MD; Brian D. Hobbs, MD; Craig Hersh, MD, MPH; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; George Washko, MD. Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH; John Austin, MD; Belinda D’Souza, MD; Byron Thomashow, MD. Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre Jr., MD; H. Page McAdams, MD; Lacey Washington, MD. Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, GA: Eric Flenaugh, MD; Silanth Terpenning, MD. HealthPartners Research Institute, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH; Joseph Tashjian, MD. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, MD; Robert Brown, MD; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Karen Horton, MD; Allison Lambert, MD, MHS; Nirupama Putcha, MD, MHS. Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovationat Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA: Richard Casaburi, PhD, MD; Alessandra Adami, PhD; Matthew Budoff, MD; Hans Fischer, MD; Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD; Harry Rossiter, PhD; William Stringer, MD. Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, PhD; Charlie Lan, DO. Minneapolis VA: Christine Wendt, MD; Brian Bell, MD; Ken M. Kunisaki, MD, MS. National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD; David A. Lynch, MB. Reliant Medical Group, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, MD; David Pace, MD. Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, MD; David Ciccolella, MD; Francis Cordova, MD; Chandra Dass, MD; Gilbert D’Alonzo, DO; Parag Desai, MD; Michael Jacobs, PharmD; Steven Kelsen, MD, PhD; Victor Kim, MD; A. James Mamary, MD; Nathaniel Marchetti, DO; Aditi Satti, MD; Kartik Shenoy, MD; Robert M. Steiner, MD; Alex Swift, MD; Irene Swift, MD; Maria Elena Vega-Sanchez, MD. University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: Mark Dransfield, MD; William Bailey, MD; Surya P. Bhatt, MD; Anand Iyer, MD; Hrudaya Nath, MD; J. Michael Wells, MD. University of California, San Diego, CA: Douglas Conrad, MD; Xavier Soler, MD, PhD; Andrew Yen, MD. University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Alejandro P. Comellas, MD; Karin F. Hoth, PhD; John Newell Jr., MD; Brad Thompson, MD. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: MeiLan K. Han, MD MS; Ella Kazerooni, MD MS; Wassim Labaki, MD MS; Craig Galban, PhD; Dharshan Vummidi, MD. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Joanne Billings, MD; Abbie Begnaud, MD; Tadashi Allen, MD. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, MD; Jessica Bon, MD; Divay Chandra, MD, MSc; Carl Fuhrman, MD; Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH. University of Texas Health, San An

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figure, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant F32HL149258-01 to V.T.] and the Baurenschmidt Award from the Johns Hopkins Eudowood Foundation (V.T.). M. H. C. was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants R01HL135142, R01 HL137927, and R01 HL147148]. The COPDGene study (NCT00608764) is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants R01 HL089897 and R01 HL089856] and the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an industry advisory board comprising AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Siemens, and Sunovion.

Contributor Information

Vickram Tejwani, Email: tejwanv@ccf.org.

COPDGene Investigators:

James D. Crapo, Edwin K. Silverman, Barry J. Make, Elizabeth A. Regan, Terri Beaty, Ferdouse Begum, Peter J. Castaldi, Michael Cho, Dawn L. DeMeo, Adel R. Boueiz, Marilyn G. Foreman, Eitan Halper-Stromberg, Lystra P. Hayden, Craig P. Hersh, Jacqueline Hetmanski, Brian D. Hobbs, John E. Hokanson, Nan Laird, Christoph Lange, Sharon M. Lutz, Merry-Lynn McDonald, Margaret M. Parker, Dmitry Prokopenko, Dandi Qiao, Elizabeth A. Regan, Phuwanat Sakornsakolpat, Edwin K. Silverman, Emily S. Wan, Sungho Won, Juan Pablo Centeno, Jean-Paul Charbonnier, Harvey O. Coxson, Craig J. Galban, MeiLan K. Han, Eric A. Hoffman, Stephen Humphries, Francine L. Jacobson, Philip F. Judy, Ella A. Kazerooni, Alex Kluiber, David A. Lynch, Pietro Nardelli, John D. Newell, Jr., Aleena Notary, Andrea Oh, Elizabeth A. Regan, James C. Ross, Raul San Jose Estepar, Joyce Schroeder, Jered Sieren, Berend C. Stoel, Juerg Tschirren, Edwin Van Beek, Bramvan Ginneken, Eva van Rikxoort, Gonzalo Vegas Sanchez-Ferrero, Lucas Veitel, George R. Washko, Carla G. Wilson, Robert Jensen, Douglas Everett, Jim Crooks, Katherine Pratte, Matt Strand, Carla G. Wilson, John E. Hokanson, Gregory Kinney, Sharon M. Lutz, Kendra A. Young, Surya P. Bhatt, Jessica Bon, Alejandro A. Diaz, MeiLan K. Han, Barry Make, Susan Murray, Elizabeth Regan, Xavier Soler, Carla G. Wilson, Russell P. Bowler, Katerina Kechris, Farnoush Banaei-Kashani, Jeffrey L. Curtis, Perry G. Pernicano, Nicola Hanania, Mustafa Atik, Aladin Boriek, Kalpatha Guntupalli, Elizabeth Guy, Amit Parulekar, Dawn L. DeMeo, Alejandro A. Diaz, Lystra P. Hayden, Brian D. Hobbs, Craig Hersh, Francine L. Jacobson, George Washko, R. Graham Barr, John Austin, Belinda D’Souza, Byron Thomashow, Neil MacIntyre, Jr., H. Page McAdams, Lacey Washington, Eric Flenaugh, Silanth Terpenning, Charlene McEvoy, Joseph Tashjian, Robert Wise, Robert Brown, Nadia N. Hansel, Karen Horton, Allison Lambert, Nirupama Putcha, Richard Casaburi, Alessandra Adami, Matthew Budoff, Hans Fischer, Janos Porszasz, Harry Rossiter, William Stringer, Amir Sharafkhaneh, Charlie Lan, Christine Wendt, Brian Bell, KenM. Kunisaki, Russell Bowler, David A. Lynch, Richard Rosiello, David Pace, Gerard Criner, David Ciccolella, Francis Cordova, Chandra Dass, Gilbert D’Alonzo, Parag Desai, Michael Jacobs, Steven Kelsen, Victor Kim, A. James Mamary, Nathaniel Marchetti, Aditi Satti, Kartik Shenoy, Robert M. Steiner, Alex Swift, Irene Swift, Maria Elena Vega-Sanchez, Mark Dransfield, William Bailey, Surya P. Bhatt, Anand Iyer, Hrudaya Nath, J. Michael Wells, Douglas Conrad, Xavier Soler, Andrew Yen, Alejandro P. Comellas, Karin F. Hoth, John Newell, Jr., Brad Thompson, MeiLan K. Han, Ella Kazerooni, Wassim Labaki, Craig Galban, Dharshan Vummidi, Joanne Billings, Abbie Begnaud, Tadashi Allen, Frank Sciurba, Jessica Bon, Divay Chandra, Carl Fuhrman, and Joel Weissfeld

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Lozano R., Naghavi M., Foreman K. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelmeier C.F., Criner G.J., Martinez F.J. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(5):557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johannessen A., Skorge T.D., Bottai M. Mortality by level of emphysema and airway wall thickness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(6):602–608. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1722OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haruna A., Muro S., Nakano Y. CT scan findings of emphysema predict mortality in COPD. Chest. 2010;138(3):635–640. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAllister D.A., Ahmed F.S., Austin J.H.M. Emphysema predicts hospitalisation and incident airflow obstruction among older smokers: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oelsner E.C., Lima J.A.C., Kawut S.M. Noninvasive tests for the diagnostic evaluation of dyspnea among outpatients: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Lung Study. Am J Med. 2015;128(2):171–180.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oelsner E.C., Hoffman E.A., Folsom A.R. Association between emphysema-like lung on cardiac computed tomography and mortality in persons without airflow obstruction. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):863–873. doi: 10.7326/M13-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Königshoff M., Kneidinger N., Eickelberg O. TGF-β signalling in COPD: deciphering genetic and cellular susceptibilities for future therapeutic regimens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(39–40):554–563. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonniaud P., Kolb M., Galt T. Smad3 null mice develop airspace enlargement and are resistant to TGF-β-mediated pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2004;173(3):2099–2108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker M.M., Hao Y., Guo F. Identification of an emphysema- associated genetic variant near TGFB2 with regulatory effects in lung fibroblasts. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.42720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrine N., Guyatt A.L., Erzurumluoglu A.M. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat Genet. 2019;51(3):481–493. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavel J., Terrón J.A., Benicky J. Increased angiotensin II AT1 receptor mRNA and binding in spleen and lung of AT2 receptor gene disrupted mice. Regul Pept. 2009;158(1–3):156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall R.P., Gohlke P., Chambers R.C. Angiotensin II and the fibroproliferative response to acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286(1):L156–L164. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00313.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Podowski M., Calvi C., Metzger S. Angiotensin receptor blockade attenuates cigarette smoke—induced lung injury and rescues lung architecture in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):229–240. doi: 10.1172/JCI46215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert A., Neptune E., Brown R. Angiotensin receptor blockade treatment for COPD: phase II trial. Chest. 2015;148(4) [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh M.A., Aaron C.P., Hoffman E.A. Angiotensin-converting inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers and longitudinal change in percent emphysema on computed tomography the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis lung study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(5):649–658. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-317OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen H., Sood A., Meek P.M. Rapid lung function decline in smokers is a risk factor for COPD and is attenuated by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use. Chest. 2014;145(4):695–703. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regan E.A., Hokanson J.E., Murphy J.R. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2010;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashraf H., Lo P., Shaker S.B. Short-term effect of changes in smoking behaviour on emphysema quantification by CT. Thorax. 2011;66(1):55–60. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.132688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman E.A., Ahmed F.S., Baumhauer H. Variation in the percent of emphysema-like lung in a healthy, nonsmoking multiethnic sample. The MESA Lung Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(6):951–955. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-364OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pompe E., Strand M., van Rikxoort E.M. Five-year progression of emphysema and air trapping at CT in smokers with and those without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the COPDGene Study. Radiology. 2020;295(1):218–226. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller M.R., Hankinson J., Brusasco V. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hankinson J.L., Odencrantz J.R., Fedan K.B. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. Population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aaron C.P., Schwartz J.E., Hoffman E.A. A longitudinal cohort study of aspirin use and progression of emphysema-like lung characteristics on CT imaging: the MESA Lung Study. Chest. 2018;154(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright J.L., Zhou S., Preobrazhenska O. Statin reverses smoke-induced pulmonary hypertension and prevents emphysema but not airway remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(1):50–58. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0399OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch D.A., Austin J.H.M., Hogg J.C. CT-definable subtypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2015;277(1):192–205. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin P.C. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(2):150–161. doi: 10.1002/pst.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coca-Perraillon M. Proceedings of NorthEast SAS Users Group Conference (NESUG) NESUG; 2006. Matching with propensity scores to reduce bias in observational studies.https://www.lexjansen.com/nesug/nesug06/an/da13.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Agostino R.B., Jr. Tutorial in biostatistics: propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis L.H., Hammill B.G., Eisenstein E.L., Kramer J.M., Anstrom K.J. Using inverse probability-weighted estimators in comparative effectiveness analyses with observational databases. Med Care. 2007;45(10 Supl 2):S103–S107. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806518ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cazzola M., MacNee W., Martinez F.J. Outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):416–468. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00099306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labaki W.W., Martinez C.H., Martinez F.J. The role of chest computed tomography in the evaluation and management of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(11):1372–1379. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0451PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zulueta J.J., Wisnivesky J.P., Henschke C.I. Emphysema scores predict death from COPD and lung cancer. Chest. 2012;141(5):1216–1223. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ash S.Y., San José Estépar R., Fain S.B. Relationship between emphysema progression at CT and mortality in ever-smokers: results from the COPDGene and ECLIPSE cohorts. Radiology. 2021;299(1):222–231. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kagami S., Border W.A., Miller D.E., Noble N.A. Angiotensin II stimulates extracellular matrix protein synthesis through induction of transforming growth factor-β expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(6):2431–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI117251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez-Vita J., Sánchez-López E., Esteban V., Rupérez M., Egido J., Ruiz-Ortega M. Angiotensin II activates the Smad pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells by a transforming growth factor-β-independent mechanism. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2509–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165133.84978.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shrikrishna D., Astin R., Kemp P.R., Hopkinson N.S. Renin-angiotensin system blockade: a novel therapeutic approach in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Sci. 2012;123(8):487–498. doi: 10.1042/CS20120081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis K.J., Meyrick V.M., Mehta B. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition as an adjunct to pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(11):1349–1357. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0094OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shrikrishna D., Tanner R.J., Lee J.Y. A randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition for skeletal muscle dysfunction in COPD. Chest. 2014;146(4):932–940. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benigni A., Cassis P., Remuzzi G. Angiotensin II revisited: new roles in inflammation, immunology and aging. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2(7):247–257. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maron B.A., Leopold J.A. The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension (2013 Grover Conference series) Pulm Circ. 2014;4(2):200–210. doi: 10.1086/675984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karnik S.S., Unal H., Kemp J.R. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCIX. Angiotensin receptors: interpreters of pathophysiological angiotensinergic stimuli. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67(4):754–819. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.010454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.