Abstract

DNA methylation, which is modulated by both genetic factors and environmental exposures, may offer a unique opportunity to discover novel biomarkers of disease-related brain phenotypes, even when measured in other tissues than brain, such as blood. A few studies of small sample sizes have revealed associations between blood DNA methylation and neuropsychopathology, however, large-scale epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) are needed to investigate the utility of DNA methylation profiling as a peripheral marker for the brain. Here, in an analysis of eleven international cohorts, totalling 3337 individuals, we report epigenome-wide meta-analyses of blood DNA methylation with volumes of the hippocampus, thalamus and nucleus accumbens (NAcc)—three subcortical regions selected for their associations with disease and heritability and volumetric variability. Analyses of individual CpGs revealed genome-wide significant associations with hippocampal volume at two loci. No significant associations were found for analyses of thalamus and nucleus accumbens volumes. Cluster-based analyses revealed additional differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with hippocampal volume. DNA methylation at these loci affected expression of proximal genes involved in learning and memory, stem cell maintenance and differentiation, fatty acid metabolism and type-2 diabetes. These DNA methylation marks, their interaction with genetic variants and their impact on gene expression offer new insights into the relationship between epigenetic variation and brain structure and may provide the basis for biomarker discovery in neurodegeneration and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Subject terms: Genetics, Molecular biology, Neuroscience

Introduction

Structural brain measures are important correlates of developmental and health outcomes across the lifetime. A large body of evidence has revealed age-related reductions in grey matter structures across the brain [1], notably in the hippocampus, which correlates with declining memory performance in older adults [2, 3]. Recent findings from large-scale neuroimaging analyses within the ENIGMA consortium have revealed consistent patterns of cortical [4, 5] and subcortical [5–8] brain volume reductions across several neuropsychiatric disorders. Of all structures reported, the hippocampus was the most consistently and robustly altered, being smaller in major depressive disorder [6], schizophrenia [7], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [8], obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [9], and posttraumatic stress disorder [10]. Other notable changes included volume reductions in the thalamus and nucleus accumbens (NAcc) in schizophrenia [7, 8], as well as volume increases in the same regions in paediatric OCD [9].

Such differences in brain structure may fundamentally reflect the effects of genetic and environmental factors and their interplay, as suggested by the study of discordant monozygotic twins [11]. DNA methylation is an epigenetic mechanism that may underlie gene–environment contributions to brain structure. It is under the influence of genetic [12, 13] and developmental [13–15] factors and plays an important role in brain development and disease, by regulating gene expression. DNA methylation is also a mechanism through which external stimuli, such as the environment, may contribute to expression of common diseases such as neurodegenerative disorders [16].

While efforts to identify genetic factors influencing brain structure have flourished in recent years [17–19], epigenetic studies of brain-related phenotypes remain very sparse. A considerable constraint is the need for a surrogate tissue for epigenetic studies of the living human brain. Crucially, while initial reports have demonstrated that although DNA methylation patterns are largely tissue-specific, often differing between blood and brain [20, 21], there are also similarities [22] and blood DNA methylation shows promise as a biomarker for brain-related traits, including neuropsychiatric disorders [23–27], cognitive ability [28, 29] and future psychopathology [26]. However, only a few studies of small sample sizes have reported associations between blood DNA methylation and brain phenotypes [26, 30–32].

Here, we built upon these findings and performed a large multisite epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) of structural brain volumes in 3337 individuals from 11 cohorts. We focussed on analyses of the hippocampus, thalamus and NAcc, based on relevance of these subcortical brain regions for disease and on heritability of these phenotypes. We selected the hippocampus as the brain structure most consistently and robustly altered in neuropsychiatric disorders, as described above. We also selected the thalamus and NAcc as subcortical regions with the highest and lowest twin-based heritability estimates, respectively [18, 33], to test a model according to which a substantial fraction of the heritability of complex traits may be due to epigenetic variation [34].

Material and methods

Subjects and brain measures

The brain phenotypes examined in this study are from the ENIGMA analysis of high-resolution MRI brain scans of volumetric measures (full details in [18]). Our analyses were focussed to mean (of left and right hemisphere) volumetric measures of three subcortical areas: the hippocampus, thalamus and NAcc, selected for their link to disease, different levels of heritability, and developmental trajectories. MRI brain scans and genome-wide DNA methylation data were available for 3337 subjects from 11 cohorts (Supplementary Table 1). All participants in all cohorts in this study gave written informed consent and sites involved obtained approval from local research ethics committees or Institutional Review Boards.

DNA methylation microarray processing and normalization

Blood DNA methylation was assessed for each study using the Illumina HumanMethylation450 (450k) microarray, which measures CpG methylation across >485,000 probes covering 99% of RefSeq gene promoters [35], following the manufacturer’s protocols. Standardised quality control procedures and quantile normalization were performed using the minfi Bioconductor package in R [36]. Please refer to Supplementary Materials and Methods for more details.

Epigenome-wide association analysis

EWAS with volumes of the thalamus, hippocampus and NAcc were performed for each site separately with standardised procedures (see Supplementary Materials and Methods for details), where control variables included sex, age, age [2], intracranial volume, methylation composition (the first four components), blood cell-type composition (the first two components), sample batches (when applicable), recruitment centres (when applicable) and disease status (when applicable). For studies with data collected across several centres, dummy-coded covariates were also included in the model.

Results from each cohort were then meta-analysed by combining correlations (fisher’s r-to-Z transformed) across all 11 cohorts with a fixed effect model, weighted by the corresponding inversed variance [37]. False discovery rates (FDR) were computed (correcting for the number of brain regions tested and the number of DNA methylation probes) and FDR < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified by applying the Comb-p algorithm [38] (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Results

Associations of DNA methylation with subcortical volumes: analyses of individual CpG sites

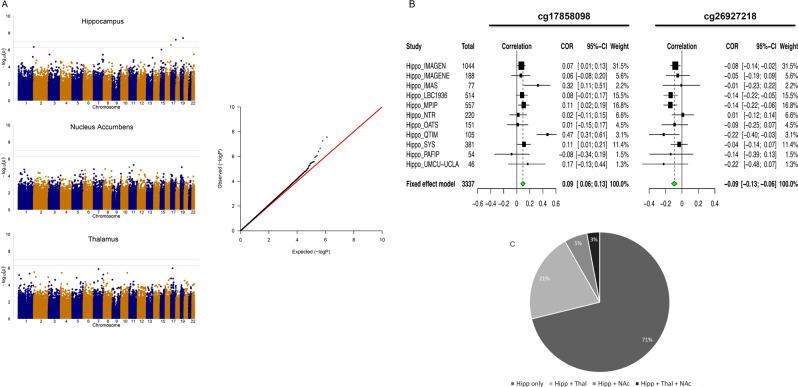

We first investigated the association of DNA methylation at individual CpG sites in whole blood samples with the mean bilateral volumes of the hippocampus, thalamus and NAcc. Meta-analysis was applied by combining correlations across all 11 cohorts with a fixed effect model, weighting for sample size. We identified two CpGs associating with the volume of the hippocampus (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table 2) at an experiment-wide (correcting for the number of brain regions tested) FDR < 0.05. The analyses of thalamus and NAcc volumes identified no CpG reaching the experiment-wide FDR threshold. Q–Q plots for the P values of the analyses showed no evidence of P value inflation. The CpGs associated with hippocampal volume explained each 0.9% of the phenotypic variance. Their effects were consistent across cohorts, with similar effect sizes for the cg26927218 site (P > 0.1, Cochran’s Q test), while moderate heterogeneity in the magnitude, but not the direction of effects was noted for cg17858098 (Fig. 1b). Effect sizes for analyses with and without patients across the 11 cohorts were very highly correlated (r ≥ 0.99) for CpGs with P < 1 × 10−3, indicating that these effects were unlikely driven by disease. These CpGs were annotated to the brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1-associated protein 2 (BAIAP2) gene (also known as IRSp53; cg26927218)—encoding a synaptic protein whose expression in the hippocampus is required for learning, memory [39] and social competence [40] and to the enoyl-CoA hydratase-1 (ECH1; cg17858098), which encodes an enzyme involved in the β-oxidation of fatty acids [41].

Fig. 1.

a Manhattan plots (left) summarizing the association results for the hippocampus, thalamus and NAcc volumes. The red and blue lines represent the genome-wide FDR significance level (corrected for three brain regions) and non-corrected FDR significance level, respectively. Quantile–quantile plots (right) of multivariate GWAS of all traits (volumes of the hippocampus, thalamus and accumbens) show that the observed P values only deviate from the expected null distribution at the most significant values, indicating no undue inflation of the results. b Forest plots show the effect (i.e. correlations between CpG methylation and hippocampus volume) at each of the contributing sites to the meta-analysis. The size of the dot is proportional to the sample size, the correlation level is shown on the x-axis, and confidence interval is represented by the line. c Pie chart of distribution of the 340 CpGs associated with hippocampus volume at P < 5 × 10−4. The chart indicates the proportion of these CpG sites that are unique to the hippocampus or that are also associated (nominally, at p < 0.05) with the two other volumetric phenotypes investigated. In general, CpGs that influence other phenotypes than hippocampus volume have higher effect on thalamus than on NAcc volume

CpGs associated with hippocampal volume showed effects specific for this structure rather than pleiotropic effects. Of the 340 CpGs associated with hippocampus volume at P < 5 × 10−4 (Supplementary Table 2), 71% were associated only with the hippocampus, 21% were shared with the thalamus and few with the NAcc (Fig. 1c). These closer epigenetic links between hippocampus and thalamus reflected closer correlations between their volumes (rH*T = 0.367, P = 5.78 × 10−34 and rH*N = 0.201, P = 8.36 × 10−11, for correlations of hippocampal volumes with thalamus and NAcc volumes, respectively).

Associations of DNA methylation with subcortical volumes: differentially methylated regions

The analyses described above did not account for effects of DNA methylation clusters at regions formed by spatially correlated CpGs, which often occur within regulatory regions in the genome and are powerful means to control gene expression. Therefore, in the following analyses, we set out to identify such DNA methylation clusters (i.e. differentially methylated regions, DMRs) by applying the comb-p algorithm [38] to our epigenome-wide meta-analyses of hippocampal volume (see Supplementary Materials and Methods). Several DMRs significantly associated with the volume of hippocampus in the meta-analysed results (Šidák [42] corrected P < 0.05, number of consecutive probes ≥E2; total numbers of DMRs = 20; Table 1). A DMR that included the cg26927218 site was identified (Pcorrected = 9.44 × 10−4), further supporting the association of BAIAP2 methylation with hippocampal volume. In addition to being identified from the meta-analysed data, three of these DMRs were identified in at least two cohorts, when analyses were run on EWAS results of each cohort separately, indicating that their association with brain volumes were unlikely to be due to chance. They were located within the cardiomyopathy associated gene 5 (CMYA5; Pcorrected = 8.47 × 10−14; this DMR is subsequently referred to as DMR1), encoding an expression biomarker for diseases affecting striated muscle [43–46] and possibly a schizophrenia risk gene [47]; the hematopoietically expressed homeobox (HHEX; Pcorrected = 9.27 × 10−5; DMR2) gene, encoding a homeobox transcription factor controlling stem cells pluripotency and differentiation in several tissues [48–52], and a well-known risk loci for type 2 diabetes [53], as well as the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B (CPT1B; Pcorrected = 2.45 × 10−4; DMR3) gene, encoding a rate-limiting enzyme in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids, whose expression enhances reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells [54], cancer cell self-renewal and chemoresistance [55]. There was a significant degree of correlation of DNA methylation at these DMRs (r = 0.155, P = 7.30 × 10−8 and r = 0.147, P = 2.91 × 10−7, for DMR1 versus DMR3 and DMR1 versus DMR2, respectively). These three DMRs were also taken forward for further analyses.

Table 1.

List of DMRs identified from the the hippocampus EWAS meta-analysis results

| Chrom no. | Start | End | n_probes | z_p | z_sidak_p | Nearest gene | Distance to TSS | Other gene | Distance to TSS | Number of cohorts individually identifying the DMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | ||||||||||

| chr5 | 78,985,425 | 78,985,593 | 9 | 3.39E−17 | 8.47E−14 | CMYA5 | −191 | 3 | ||

| chr7 | 149,569,715 | 149,570,184 | 12 | 4.34E−08 | 3.88E−05 | ATP6V0E2 | −107 | 1 | ||

| chr10 | 94,455,543 | 94,455,896 | 4 | 7.79E−08 | 9.27E−05 | HHEX | 7775 | EXOC6 | −152,557 | 2 |

| chr14 | 23,623,480 | 23,623,936 | 6 | 1.24E−07 | 1.14E−04 | CEBPE | −34,883 | SLC7A8 | 29,141 | 0 |

| chr22 | 51,016,501 | 51,016,900 | 7 | 2.33E−07 | 2.45E−04 | CPT1B | 395 | 2 | ||

| chr3 | 130,745,442 | 130,745,686 | 10 | 4.63E−07 | 7.97E−04 | NEK11 | −163 | ASTE1 | 82 | 0 |

| chr2 | 161,504,772 | 161,504,906 | 3 | 2.65E−07 | 8.30E−04 | TANK | −511,969 | RBMS1 | −154,534 | 0 |

| chr7 | 130,626,376 | 130,626,560 | 3 | 3.83E−07 | 8.73E−04 | MKLN1 | −386,151 | KLF14 | −207,580 | 0 |

| chr17 | 79,053,905 | 79,054,074 | 3 | 3.80E−07 | 9.44E−04 | BAIAP2 | 45,028 | AATK | 85,827 | 0 |

| chr8 | 66,472,662 | 66,472,956 | 3 | 9.33E−07 | 1.33E−03 | CYP7B1 | −761,491 | ARMC1 | 73,633 | 0 |

| chr7 | 29,605,808 | 29,606,350 | 4 | 2.04E−06 | 1.58E−03 | WIPF3 | –268,262 | PRR15 | 2652 | 0 |

| chr17 | 80,195,101 | 80,195,403 | 3 | 1.51E−06 | 2.09E−03 | SLC16A3 | 3689 | CSNK1D | 36,355 | 0 |

| chr22 | 43,739,992 | 43,740,231 | 3 | 1.48E−06 | 2.59E–03 | SCUBE1 | −718 | 0 | ||

| chr4 | 3,365,280 | 3,365,443 | 4 | 2.12E−06 | 5.44E−03 | HGFAC | –78,252 | RGS12 | 49,488 | 0 |

| chr17 | 81,028,481 | 81,028,497 | 2 | 3.24E−07 | 8.47E–03 | B3GNTL1 | –18,803 | METRNL | −9078 | 0 |

| chr2 | 3,699,195 | 3,699,354 | 4 | 5.24E−06 | 1.37E−02 | ALLC | −6510 | COLEC11 | 49,779 | 0 |

| chr22 | 43,525,330 | 43,525,432 | 2 | 3.86E−06 | 1.58E−02 | MCAT | 14,019 | BIK | 18,627 | 0 |

| chr22 | 38,506,589 | 38,506,782 | 4 | 1.09E−05 | 2.34E−02 | BAIAP2L2 | −9 | 0 | ||

| chr2 | 236,100,688 | 236,100,752 | 3 | 4.77E−06 | 3.08E−02 | AGAP1 | −302,031 | SH3BP4 | 213,391 | 0 |

| chr7 | 155,150,681 | 155,150,794 | 2 | 9.95E−06 | 3.63E−02 | EN2 | −100,086 | INSIG1 | 61,252 | 0 |

Bold values represent 3 DMRs taken forward for further analyses because, in addition to being identified from the meta-analysis, they were also identified in at least two cohorts, when analyses were run in each cohort separately.

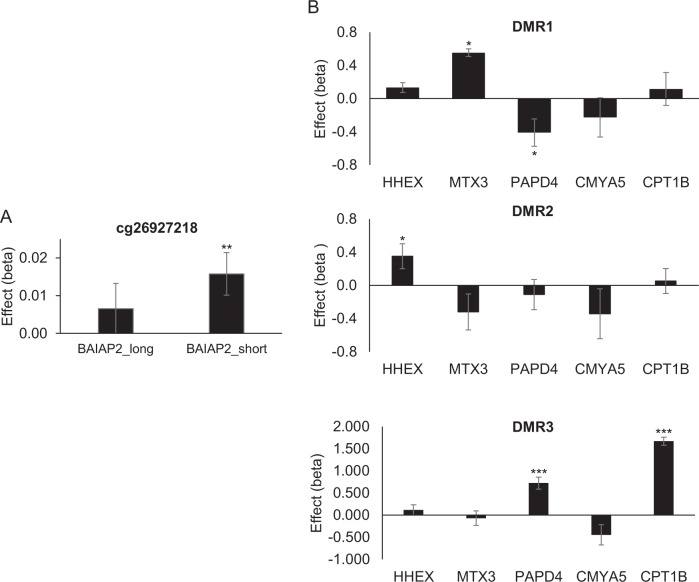

Effects of differential methylation on gene expression

We measured the impact of DNA methylation on expression of neighbouring genes (cis-effects) in 631 IMAGEN subjects for which DNA methylation and mRNA expression data were available (see Supplementary Materials and Methods). Methylation at most loci affected gene expression, with the effects of DMRs being larger than that of individual CpGs (i.e. cg26927218). Several isoforms are expressed from BAIAP2, and isoform-specific effects were observed for cg26927218; methylation at this locus correlated with increased expression of the short isoform for BAIAP2 (β = 0.016, P = 5 × 10−3; Fig. 2a). There were no significant effects of cg17858098 on ECH1 mRNA levels (β = −0.008, P = 0.201). Given the correlations between the selected three DMRs noted above, we controlled for methylation at the other two DMRs when testing for effects of a given DMR on gene expression. As shown in Fig. 2b, DMR1 methylation had no effect on expression of CMYA5 (β = −0.227, P = 0.492), tending instead to have contrasting effects on expression of neighbouring genes (β = −0.410, P = 0.039 and β = 0.554, P = 0.019 for PAPD4 and MTX3, respectively). Methylation at DMR2 increased expression of its closest gene, HHEX (β = 0.351, P = 0.020). Methylation at DMR3 had strong effects on expression of the adjacent CPT1B gene (β = 1.670, P = 2.55 × 10−59). Trans-effects were also noted for this DMR, as it associated with increased expression of PAPD4 (β = 0.724, P = 1.21 × 10−7), a gene adjacent to DMR1.

Fig. 2.

Analyses of top CpG (a) and DMRs (b) demonstrate effects of DNA methylation on gene expression in 631 subjects from the IMAGEN sample. In the DMR analyses, linear regression analyses tested relationship between methylation at the listed DMR and expression of HHEX, MTX3, PAPD4, CMYA5 and CPT1B, controlling for methylation at the other two DMRs. Results represent unstandardized coefficients ± S.E.M. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Correlations of DNA methylation between blood and brain

To investigate if the above findings would remain relevant for the brain, we first compared methylation levels at the selected differentially methylated loci (i.e. two CpG sites and three DMRs) in blood and brain tissues sampled from the same individuals to establish the degree to which blood methylation levels at selected loci correlated with their brain methylation patterns. Then, we compared the degree of these blood–brain covariations (i.e. the extent to which of DNA methylation in blood correlated with DNA methylation in brain) to the corresponding Z-values from the hippocampal EWAS. We evaluated these effects across all three DMRs, as well as within each DMR. It is important to point out that higher degree of blood–brain covariations in methylation, which indicates a higher proportion of shared information between blood and brain, would result in increased strength in association between blood DNA methylation and hippocampus volume, solely if this association was indeed mediated by brain DNA methylation. Please see Supplementary Materials and Methods for details of the approach.

We compared methylation levels at these sites in blood and brain tissues (prefrontal cortex, entorhinal cortex, superior temporal gyrus and cerebellum) sampled from the same individuals (N = 75) using the blood–brain DNA methylation comparison tool [56] (see Supplementary Materials and Methods; Supplementary Table 3). There was no significant correlation between blood and brain methylation levels at the individual CpG sites (cg26927218—BAIAP2 and cg17858098—ECH1). On the other hand, interindividual variation in whole blood was a moderate predictor of interindividual variation in all tested cortical brain areas for DMR1 and DMR3 (strongest correlations: r = 0.54, P = 1.20 × 10−6 and r = 0.59, P = 2.37 × 10−8, respectively; Supplementary Table 3). For DMR2, correlations were more varied with the strongest correlation in the superior temporal gyrus (r = 0.37, P = 9.68 × 10–4; Supplementary Table 3). Generally, correlations were stronger in cortical brain regions than in the cerebellum. Crucially, the degree of blood–brain covariations in DNA methylation at these sites predicted associations between blood DNA methylation and hippocampus volume with moderate to large effect sizes (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1). These effects were particularly notable in the superior temporal gyrus, across all three DMRs (r = 0.751, t = 4.54, df = 16, Pone tailed = 6.6 × 10−3 after Bonferroni correction for four brain regions), and at each DMR (r = 0.707, t = 2.65, df = 7, Pone tailed = 0.017 for DMR1; r = 0.964, t = 5.14, df = 2, Pone tailed = 0.018 for DMR2; r = −0.748, t = −2.52, df = 5, Pone tailed = 0.027 for DMR3). There was also moderate prediction by the degree of covariation of DNA methylation in prefrontal cortex, across all three DMRs (r = 0.417, t = 1.84, df = 16, Pone tailed = 0.042), and with DMR2 (r = 0.966, t = 5.26, df = 2, Pone tailed = 0.017). These results strongly suggest that associations between hippocampal volume and blood DNA methylation levels at the selected DMRs are largely mediated by their DNA methylation levels in the brain (see Supplementary Materials and Methods for more details).

Another comparison between methylation in blood and other brain regions—Brodmann area (BA)7 (parietal cortex); BA10 (anterior prefrontal cortex) and BA20 (ventral temporal cortex)—using a smaller dataset of 16 BECon post-mortem samples [57] revealed similar patterns (see Supplementary Materials and Methods; Supplementary Fig. 2). For DMR1, there were moderate correlations between blood and BA7 methylation at all CpGs (r = 0.13–0.47) and between blood and BA10 for most CpGs (r = 0.13–0.30). For DMR3, correlations between blood and brain methylation were strong in all areas (r = 0.37–0.86), while the degree of correlations varied at DMR2 ranging from −0.35 to 0.34, depending on the CpG site and the brain area.

Genetic contributions to differential DNA methylation associated with hippocampal volume

Given that genetic factors may underlie the correlations between DNA methylation in different tissues, we searched for methylation QTLs in two datasets. A search in the ARIES mQTL database [58] identified several SNPs associated with methylation at the DMR1 and DMR3 loci (see Supplementary Materials and Methods; Supplementary Table 5A). The strongest mQTLs, rs131758 and rs4441859, affected methylation such that the A-allele at these SNPs associated with increased methylation at DMR3 and DMR1, respectively. These effects were replicated in two other datasets [59, 60] (see Supplementary Materials and Methods; Supplementary Table 5B). Remarkably, eQTL analyses indicated that these alleles correlated with expressions of CMYA5 and CPT1B, albeit differently. While the effects of the rs4441859_A allele were tissue-specific, the rs131758_A allele increased CPT1B expression in all tissues, including the brain (Supplementary Table 5C and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Furthermore, we considered whether there was a significant overlap between DNA methylation differences identified in this study and SNPs associated with hippocampal volume. To test this, we used the recent genome-wide association studies of hippocampal volume conducted by ENIGMA [18] (excluding the IMAGEN data; GWAS association thresholds P < 5 × 10–6 and P < 5 × 10−7) as a dataset for significant hippocampal SNP regions, adapting MAGENTA [61] (see Supplementary Materials and Methods), the gene sets-based enrichment analysis tool for GWAS data to the analysis of methylation data. SNPs were merged into genomic regions that were then examined for overlap with DNA methylation identified in hippocampal EWAS performed in the IMAGEN sample. These analyses revealed a significant overlap between DNA methylation loci and SNP loci influencing hippocampal volume (Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

In this large epigenome-wide meta-analysis we identified for the first time differentially methylated CpG sites and genomic regions whose levels of DNA methylation correlate with variation in hippocampal volume. We further demonstrate the potential of using blood to discover epigenetic biomarkers for the living human brain. Methylation at these sites affect the expression of genes required for hippocampal function and metabolic regulation. At the identified sites, the observation that DNA methylation variation in blood can mirror that of brain tissues, and that the degree of this covariation could predict the association of blood DNA methylation with hippocampus volume, helps us generate hypotheses as to how modifiable factors such as diet and lifestyle may contribute to some of the impairments associated with diabetes and neurodegenerative conditions [62].

Changes in hippocampal volumes are hallmarks of brain development predictive of cognitive deficits generally associated with aging and neurodegeneration. While large hippocampal volume is linked with good memory and cognitive function, hippocampal atrophy is associated with the development of a range of neurodegenerative [63] and neuropsychiatric disorders [6–8, 10]. Modifiable factors such as obesity, exercise, stress and medication can reduce or increase the size of the hippocampus throughout life [63]. Collectively, our findings support these observations, pointing to associations of hippocampal volume with fatty acid metabolism, as discussed below.

Two of the top hits identified (CPT1B and ECH1) encode key enzymes involved in β-oxidation of fatty acids. These enzymes act on the same pathway, CPT1B being necessary for the transport of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria and ECH1 for a key step in their β-oxidation. Fatty acids (notably the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids) benefit brain development and healthy brain aging by modulating neurogenesis and protecting from oxidative stress throughout the lifespan [64]. More specifically, neural precursors in the hippocampus and subventricular zone require fatty acid oxidation for proliferation [65]. This led to the proposition that abnormalities in brain lipid metabolism contribute to hippocampal dysfunction in AD by their ability to suppress neurogenesis at early stages of disease pathogenesis [66]. Accordingly, fatty acid metabolism in the brain seems to be closely related to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [67].

Further links between metabolism and hippocampal volume were suggested by our identification of a region annotated to a replicated risk locus for T2D (HHEX) [53]. The metabolic alterations observed in T2D may induce cognitive dysfunction [68] by exacerbating declines in hippocampal volumes associated with aging [69] and AD pathology [70], a process to which HHEX may contribute [71]. This is supported by findings that genetic variations within the HHEX gene region may underlie the association of T2D with AD, with the HHEX rs1544210_AA genotype interacting with diabetes to increase the risk of dementia and AD by more than fourfold [71]. Furthermore, individuals with diabetes who carry the HHEX rs1544210_AA genotype tend to have significantly smaller hippocampal volumes than those without these conditions [71].

DNA methylation at most loci had clear, albeit distinct effects on gene expression. Notable transcript-specific effects were observed for cg26927218 on BAIAP2. The cg26927218 locus is located in a DNase I hypersensitive site, characteristic of regions actively involved in transcriptional regulation [72], within a consensus DNA binding sequence for the MYC associated factor X (MAX)—a transcription factor controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. MAX belongs to a class of transcription factors that recognize CpG-containing DNA binding sequences, only in their unmethylated form [73, 74]. Thus, methylation at cg26927218 may affect expression of the BAIAP2 short variant by directly interfering with the function of this transcription factor. A role for the region surrounding cg26927218 in transcriptional regulation is further supported by findings showing that a genetic variant (rs8070741) near cg26927218 enhances cortical expression of the BAIAP2 short variant [75].

Besides the hippocampus, none of the other two subcortical structures investigated generated significant results. This may reflect a unique role of the hippocampus in brain development, possibly related to it being a site of neurogenesis. These findings are also consistent with the relative heritability of the different subcortical structures, indicating higher twin-based heritability estimates for larger (hippocampus and thalamus) compared with smaller (NAcc) subcortical structures but overall low SNP-based heritability [18]. This supports the model according to which a substantial fraction of the heritability of complex traits is due to epigenetic variation [34]. Our analyses on genetic contributions to DMRs’ effects also suggest that epigenetic control is partially modulated by genetic variations, which is further suggested by the overlap between GWAS and EWAS of hippocampal volume.

In conclusion, we have identified DNA methylation at several loci that correlate with hippocampus volume, which suggest for the first time possible biological pathways by which modifiable and metabolic factors might contribute to the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. A clear limitation is the small number of cohorts for which both MRI and DNA methylation data are available, we nonetheless provide a rigorous roadmap that should encourage larger and more extensive future studies. We also acknowledge several other limitations, such as the shortage of datasets enabling direct comparison of blood and brain DNA methylation patterns. In particular, the lack of datasets including the hippocampus as a brain region prevented us from establishing a direct link between DNA methylation in blood and in the hippocampus. However, we do provide evidence showing that DNA methylation in the superior temporal gyrus mediates associations between blood DNA methylation and hippocampal volume. Also, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, none of the associations identified can be claimed to be causal. Nevertheless, our work demonstrates the usefulness of combining peripheral DNA methylation markers and neuroimaging measures for biomarker discovery in common neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Paper writing and editing: SD wrote the paper; BR, EBB, FH, GS, JL, NF, PMT, PS, SE, TC-R, TJ, TJE, TP, UB, VC, VF and ZP edited the first draft; all authors critically reviewed the paper. Cohort principal investigators: AS, BC-F, DA, DIB, EBB, GS, HB, IJD, JT, LGA, MJW, MW, PRS, PSS, RAO, VC and ZP. Imaging data acquisition: AdB, DvE, EA, FN, GIZ, HF, J-LM, JJ, JL, JT, KLM, LTS, MEB, MH, PMT, PS, RB, TB, TP, VF, WC and WW. Epigenetic data acquisition: AFM, AT, DS, GB, JL, JS, JvD, JT, KAM, NGM, PS,TC-R, TJ, YL and ZP. Data analysis: AO, BR, CC, EP, JL, JS, JvD, KS, ML, NA, NJ, RJ, RR-S, SD,TC-R and TJ.

Code availability

The protocols used for testing association and meta-analysis and the meta-analytic results will be freely available from the ENIGMA consortium webpage upon publication (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/ and http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/research/downloadenigma-gwas-results).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

TB served in an advisory or consultancy role for Actelion, Hexal Pharma, Lilly, Lundbeck, Medice, Novartis, Shire. He received conference support or speaker’s fee by Lilly, Medice, Novartis and Shire. He has been involved in clinical trials conducted by Shire and Viforpharma. He received royalities from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, CIP Medien, Oxford University Press. The present work is unrelated to the above grants and relationships. HW received a speaker honorarium from Servier (2014). The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Paul M. Thompson, Gunter Schumann

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41380-019-0605-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Salat DH, Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Greve DN, Desikan RS, Busa E, et al. Thinning of the cerebral cortex in aging. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:721–30. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persson J, Nyberg L, Lind J, Larsson A, Nilsson LG, Ingvar M, et al. Structure-function correlates of cognitive decline in aging. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:907–15. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persson J, Pudas S, Lind J, Kauppi K, Nilsson LG, Nyberg L. Longitudinal structure-function correlates in elderly reveal MTL dysfunction with cognitive decline. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:2297–304. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibar DP, Westlye LT, Doan NT, Jahanshad N, Cheung JW, Ching CRK, et al. Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder: an MRI analysis of 6503 individuals from the ENIGMA bipolar disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:932–42. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rooij D, Anagnostou E, Arango C, Auzias G, Behrmann M, Busatto GF, et al. Cortical and subcortical brain morphometry differences between patients with autism spectrum disorder and healthy individuals across the lifespan: results from the ENIGMA ASD working group. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:359–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, van Erp TG, Samann PG, Frodl T, Jahanshad N, et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:806–12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Erp TG, Hibar DP, Rasmussen JM, Glahn DC, Pearlson GD, Andreassen OA, et al. Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:547–53. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoogman M, Bralten J, Hibar DP, Mennes M, Zwiers MP, Schweren LSJ, et al. Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:310–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boedhoe PSW, Schmaal L, Abe Y, Alonso P, Ameis SH, Anticevic A, et al. Cortical abnormalities associated with pediatric and adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA obsessive-compulsive disorder working group. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:453–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17050485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logue MW, van Rooij SJH, Dennis EL, Davis SL, Hayes JP, Stevens JS, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multisite ENIGMA-PGC study: subcortical volumetry results from posttraumatic stress disorder consortia. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suddath RL, Christison GW, Torrey EF, Casanova MF, Weinberger DR. Anatomical abnormalities in the brains of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:789–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003223221201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs JR, van der Brug MP, Hernandez DG, Traynor BJ, Nalls MA, Lai SL, et al. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaminsky ZA, Tang T, Wang SC, Ptak C, Oh GH, Wong AH, et al. DNA methylation profiles in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Nat Genet. 2009;41:240–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR, Urich M, Puddifoot CA, Johnson ND, et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science. 2013;341:1237905. doi: 10.1126/science.1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Dongen J, Nivard MG, Willemsen G, Hottenga JJ, Helmer Q, Dolan CV, et al. Genetic and environmental influences interact with age and sex in shaping the human methylome. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11115. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang JY, Aromolaran KA, Zukin RS. The emerging field of epigenetics in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:347–61. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein JL, Medland SE, Vasquez AA, Hibar DP, Senstad RE, Winkler AM, et al. Identification of common variants associated with human hippocampal and intracranial volumes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:552–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibar DP, Stein JL, Renteria ME, Arias-Vasquez A, Desrivieres S, Jahanshad N, et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature. 2015;520:224–9. doi: 10.1038/nature14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desrivières S, Lourdusamy A, Tao C, Toro R, Jia T, Loth E, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the neuroplastin locus associates with cortical thickness and intellectual ability in adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:263–74. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies MN, Volta M, Pidsley R, Lunnon K, Dixit A, Lovestone S, et al. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horvath S, Zhang Y, Langfelder P, Kahn RS, Boks MP, van Eijk K, et al. Aging effects on DNA methylation modules in human brain and blood tissue. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R97. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walton E, Hass J, Liu J, Roffman JL, Bernardoni F, Roessner V, et al. Correspondence of DNA methylation between blood and brain tissue and its application to schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:406–14. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melas PA, Rogdaki M, Osby U, Schalling M, Lavebratt C, Ekstrom TJ. Epigenetic aberrations in leukocytes of patients with schizophrenia: association of global DNA methylation with antipsychotic drug treatment and disease onset. Faseb J. 2012;26:2712–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lunnon K, Smith R, Hannon E, De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Volta M, et al. Methylomic profiling implicates cortical deregulation of ANK1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1164–70. doi: 10.1038/nn.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montano C, Taub MA, Jaffe A, Briem E, Feinberg JI, Trygvadottir R, et al. Association of DNA methylation differences with schizophrenia in an epigenome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:506–14. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggeri B, Nymberg C, Vuoksimaa E, Lourdusamy A, Wong CP, Carvalho FM, et al. Association of protein phosphatase PPM1G with alcohol use disorder and brain activity during behavioral control in a genome-wide methylation analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:543–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klengel T, Pape J, Binder EB, Mehta D. The role of DNA methylation in stress-related psychiatric disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2014;80:115–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marioni RE, McRae AF, Bressler J, Colicino E, Hannon E, Li S et al. Meta-analysis of epigenome-wide association studies of cognitive abilities. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:2133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kaminski JA, Schlagenhauf F, Rapp M, Awasthi S, Ruggeri B, Deserno L, et al. Epigenetic variance in dopamine D2 receptor: a marker of IQ malleability? Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:169. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0222-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Siyahhan Julnes P, Chen J, Ehrlich S, Walton E, Calhoun VD. The association of DNA methylation and brain volume in healthy individuals and schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2015;169:447–52. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin D, Chen J, Ehrlich S, Bustillo JR, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Walton E, et al. Cross-tissue exploration of genetic and epigenetic effects on brain gray matter in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:443–52. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freytag V, Carrillo-Roa T, Milnik A, Samann PG, Vukojevic V, Coynel D, et al. A peripheral epigenetic signature of immune system genes is linked to neocortical thickness and memory. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15193. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.den Braber A, Bohlken MM, Brouwer RM, van ‘t Ent D, Kanai R, Kahn RS, et al. Heritability of subcortical brain measures: a perspective for future genome-wide association studies. Neuroimage. 2013;83:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cortijo S, Wardenaar R, Colome-Tatche M, Gilly A, Etcheverry M, Labadie K, et al. Mapping the epigenetic basis of complex traits. Science. 2014;343:1145–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1248127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandoval J, Heyn H, Moran S, Serra-Musach J, Pujana MA, Bibikova M, et al. Validation of a DNA methylation microarray for 450,000 CpG sites in the human genome. Epigenetics. 2011;6:692–702. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.6.16196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1363–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Field AP. Is the meta-analysis of correlation coefficients accurate when population correlations vary? Psychol Methods. 2005;10:444–67. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen BS, Schwartz DA, Yang IV, Kechris KJ. Comb-p: software for combining, analyzing, grouping and correcting spatially correlated P-values. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2986–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim MH, Choi J, Yang J, Chung W, Kim JH, Paik SK, et al. Enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission, enhanced long-term potentiation, and impaired learning and memory in mice lacking IRSp53. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1586–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4306-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung W, Choi SY, Lee E, Park H, Kang J, Park H, et al. Social deficits in IRSp53 mutant mice improved by NMDAR and mGluR5 suppression. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:435–43. doi: 10.1038/nn.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Filppula SA, Yagi AI, Kilpelainen SH, Novikov D, FitzPatrick DR, Vihinen M, et al. Delta3,5-delta2,4-dienoyl-CoA isomerase from rat liver. Molecular characterization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:349–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sidak Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62:626–33. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benson MA, Tinsley CL, Blake DJ. Myospryn is a novel binding partner for dysbindin in muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10450–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312664200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durham JT, Brand OM, Arnold M, Reynolds JG, Muthukumar L, Weiler H, et al. Myospryn is a direct transcriptional target for MEF2A that encodes a striated muscle, alpha-actinin-interacting, costamere-localized protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6841–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kielbasa OM, Reynolds JG, Wu CL, Snyder CM, Cho MY, Weiler H, et al. Myospryn is a calcineurin-interacting protein that negatively modulates slow-fiber-type transformation and skeletal muscle regeneration. FASEB J. 2011;25:2276–86. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynolds JG, McCalmon SA, Donaghey JA, Naya FJ. Deregulated protein kinase A signaling and myospryn expression in muscular dystrophy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8070–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X, Lee G, Maher BS, Fanous AH, Chen J, Zhao Z, et al. GWA study data mining and independent replication identify cardiomyopathy-associated 5 (CMYA5) as a risk gene for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:1117–29. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shields BJ, Jackson JT, Metcalf D, Shi W, Huang Q, Garnham AL, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia requires Hhex to enable PRC2-mediated epigenetic repression of Cdkn2a. Genes Dev. 2016;30:78–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.268425.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodings C, Smith E, Mathias E, Elliott N, Cleveland SM, Tripathi RM, et al. Hhex is required at multiple stages of adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2628–41. doi: 10.1002/stem.2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogue CW, Zhang PX, McGrath J, Jacobs HC, Fuleihan RL. Impaired B cell development and function in mice with a targeted disruption of the homeobox gene Hex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:556–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0236979100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, McKenna LB, Bogue CW, Kaestner KH. The diabetes gene Hhex maintains delta-cell differentiation and islet function. Genes Dev. 2014;28:829–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.235499.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simpson MT, Venkatesh I, Callif BL, Thiel LK, Coley DM, Winsor KN, et al. The tumor suppressor HHEX inhibits axon growth when prematurely expressed in developing central nervous system neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2015;68:272–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J, Dina C, Shen L, Serre D, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin Z, Liu F, Shi P, Song A, Huang Z, Zou D, et al. Fatty acid oxidation promotes reprogramming by enhancing oxidative phosphorylation and inhibiting protein kinase C. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:47. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0792-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang T, Fahrmann JF, Lee H, Li YJ, Tripathi SC, Yue C, et al. JAK/STAT3-regulated fatty acid beta-oxidation is critical for breast cancer stem cell self-renewal and chemoresistance. Cell Metab. 2018;27:136–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hannon E, Lunnon K, Schalkwyk L, Mill J. Interindividual methylomic variation across blood, cortex, and cerebellum: implications for epigenetic studies of neurological and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Epigenetics. 2015;10:1024–32. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1100786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edgar RD, Jones MJ, Meaney MJ, Turecki G, Kobor MS. BECon: a tool for interpreting DNA methylation findings from blood in the context of brain. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1187. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaunt TR, Shihab HA, Hemani G, Min JL, Woodward G, Lyttleton O, et al. Systematic identification of genetic influences on methylation across the human life course. Genome Biol. 2016;17:61. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0926-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deary IJ, Gow AJ, Pattie A, Starr JM. Cohort profile: the Lothian Birth Cohorts of 1921 and 1936. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1576–84. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McRae AF, Marioni RE, Shah S, Yang J, Powell JE, Harris SE, et al. Identification of 55,000 replicated dna methylation QTL. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17605. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35871-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Segre AV, Groop L, Mootha VK, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Common inherited variation in mitochondrial genes is not enriched for associations with type 2 diabetes or related glycemic traits. PLoS Genet. 2010;6: pii: e1001058. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Stranahan AM. Models and mechanisms for hippocampal dysfunction in obesity and diabetes. Neuroscience. 2015;309:125–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fotuhi M, Do D, Jack C. Modifiable factors that alter the size of the hippocampus with ageing. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:189–202. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Innis SM. Dietary (n-3) fatty acids and brain development. J Nutr. 2007;137:855–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Knobloch M, Braun SM, Zurkirchen L, von Schoultz C, Zamboni N, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, et al. Metabolic control of adult neural stem cell activity by Fasn-dependent lipogenesis. Nature. 2013;493:226–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamilton LK, Dufresne M, Joppe SE, Petryszyn S, Aumont A, Calon F, et al. Aberrant lipid metabolism in the forebrain niche suppresses adult neural stem cell proliferation in an animal model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Snowden SG, Ebshiana AA, Hye A, An Y, Pletnikova O, O’Brien R, et al. Association between fatty acid metabolism in the brain and Alzheimer disease neuropathology and cognitive performance: a nontargeted metabolomic study. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Biessels GJ, Reagan LP. Hippocampal insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:660–71. doi: 10.1038/nrn4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raji CA, Ho AJ, Parikshak NN, Becker JT, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, et al. Brain structure and obesity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:353–64. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ho AJ, Raji CA, Saharan P, DeGiorgio A, Madsen SK, Hibar DP, et al. Hippocampal volume is related to body mass index in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport. 2011;22:10–14. doi: 10.1097/wnr.0b013e3283412868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu WL, Pedersen NL, Keller L, Kalpouzos G, Wang HX, Graff C, et al. HHEX_23 AA genotype exacerbates effect of diabetes on Dementia and Alzheimer Disease: a population-based longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yin Y, Morgunova E, Jolma A, Kaasinen E, Sahu B, Khund-Sayeed S et al. Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science. 2017;356: pii: eaaj2239. 10.1126/science.aaj2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Wang D, Hashimoto H, Zhang X, Barwick BG, Lonial S, Boise LH, et al. MAX is an epigenetic sensor of 5-carboxylcytosine and is altered in multiple myeloma. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:2396–407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luksys G, Ackermann S, Coynel D, Fastenrath M, Gschwind L, Heck A, et al. BAIAP2 is related to emotional modulation of human memory strength. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The protocols used for testing association and meta-analysis and the meta-analytic results will be freely available from the ENIGMA consortium webpage upon publication (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/ and http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/research/downloadenigma-gwas-results).