Development of a plastic surgery (PS) integrated residency program (IRP) at an institution requires careful consideration of budget, as well as faculty, administrative, and educational space.1 IRPs are rapidly expanding the educational framework of PS, necessitating a review of the characteristics of institutions that have successfully implemented a PS IRP.

We hypothesize that establishment of IRPs is linked to successful grant acquisition by faculty. Institutions support faculty members who have attained grants, and thus, many implement an IRP to promote the research endeavors of their plastic surgeons.1 Grant money is also a distinguishing factor in the NRMP’s record of IRP applicants; 34.2% of PS trainees matriculated from a top 40 grant-receiving school in 2020, compared with 28% of those unmatched, suggesting that grant awards may represent a sense of prestige in one’s pedigree.2

To investigate the correlation between PS IRP and grant money, a list of US MD medical schools (AAMC) and total grant awards for all faculty at each institution were recorded from the National Institutes of Health Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (NIH RePORT) and the US Department of Defense (DOD), and those medical schools missing from RePORT were excluded. Schools were categorized as those with and without a PS IRP. All DOD funding agencies and NIH grants in 2020 were totaled for each institution. The two groups were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test.

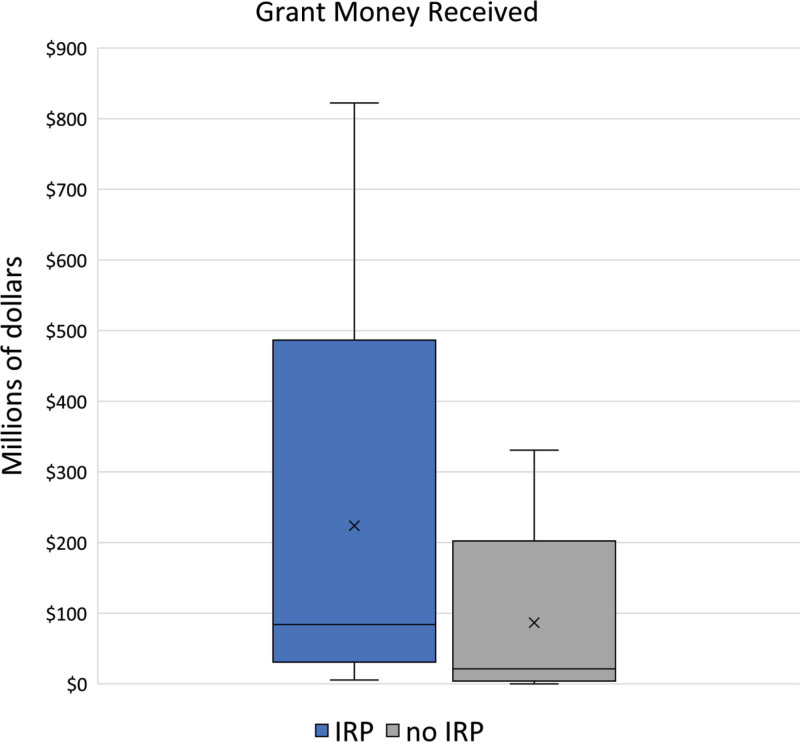

Institutions with a PS IRP were found to have significantly more grant money when compared with those without (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The three institutions with the most grant money all have IRPs, and the first institution without an IRP was identified after 20 institutions with IRP. Six percent of schools with IRPs had less than $10,000,000 in funding, whereas 33.8% of schools with no IRP fell below that threshold. The mean grant amount for IRP institutions lies above the interquartile range of the schools without IRP (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Grant Money Received from the NIH and DOD

| Integrated Program | No Integrated Program | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average grant money | $225,075,518 | $47,157,651 | ||

| Top 3 programs (dollars) | Johns Hopkins | 822,238,926 | Univ. of Alabama | 330,954,792 |

| UCSF | 685,608,202 | Boston Univ. | 233,371,910 | |

| UCLA | 677,424,653 | Univ. of Iowa | 196,921,024 | |

Comparison of grant money awarded by the NIH and DOD between institutions with and without an integrated plastic surgery program. Averages for each category and top three receiving institutions are listed.

Fig. 1.

The mean (X), median, interquartile range, and minimum/maximum for both IRP and no IRP categories.

Previous studies indicate that financial support is not required for influence in PS research.3 Nonetheless, our results indicate that the presence of an IRP is associated with top grant-receiving institutions. Larger amounts of funding at an institution should be investigated as a potential causative factor in IRP establishment. Should one of the three top institutions without IRPs develop one in the near future, this would support our results.

By striving to improve research productivity through the acquisition of grants, schools effectively add to their level of prestige5 and cultivate an environment that is financially and academically fertile for IRP initiation.1 The concept of prestige, carried by the achievements of an institution, enhances a student’s profile and prospects. The new pass/fail method of step 1 yields room for school reputation, and thus prestige, to serve as a pertinent factor in applicant selection.4 One may assume that if an institution has a substantial amount of grant money and has consequently established an IRP, as shown in our results, this combined sense of prestige may positively influence a student’s outcome in matching to PS.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Janis receives royalties from Thieme and Spring Publishing. All the other authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Published online 28 October 2021.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodbred A, Snyder R, Sweeney J, et al. Starting new accreditation council for graduate medical education (ACGME) residency programs in a teaching hospital. In: Contemporary Topics in Graduate Medical Education. Vol 2. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Resident Matching Program. National Resident Matching Program, results and data: 2020. Washington, D.C.: National Resident Matching Program; 2020. Available at http://www.nrmp.org/report-archives/. Accessed on July 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asserson DB, Janis JE. Majority of most-cited articles in top plastic surgery journals do not receive funding. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41:NP935–NP938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin LO, Makhoul AT, Hackenberger PN, et al. Implications of Pass/Fail USMLE step 1 scoring: the plastic surgery program director and applicant perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e3266.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J. Prestige, rankings, and competition for status. In: Controversies on Campus: Debating the Issues Confronting American Universities in the 21st Century. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger; 2018: 99–133. [Google Scholar]