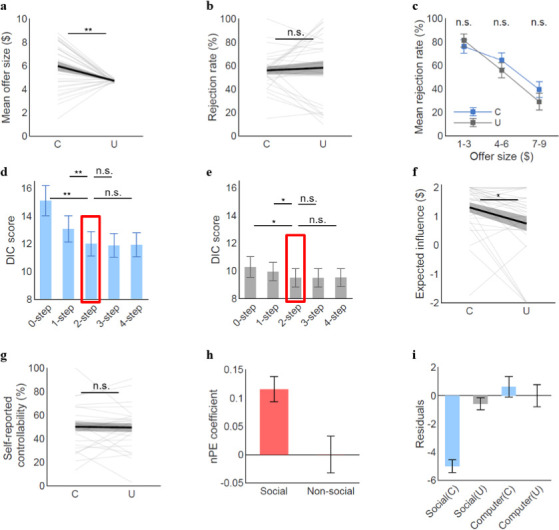

To investigate whether our results are specific to the social domain, we ran another batch of the task in which 27 out of the 48 original participants were re-contacted with a 14- to 24-month temporal gap and played the same game with the instruction of ‘playing with computer’ instead of ‘playing with virtual human partners.’ Overall, we found choice patterns (

a–f) similar to those in the social task, while the subjective states (i.e., self-reported controllability) (

g) and the impact of the norm prediction error on the emotion ratings (

Supplementary file 1) differed from the social task. (

a) Similar to the results of the social task, offers (mean

C=6.0, mean

U=4.7, t(26.23)=3.03, p<0.01) were higher for the Controllable than the Uncontrollable. (

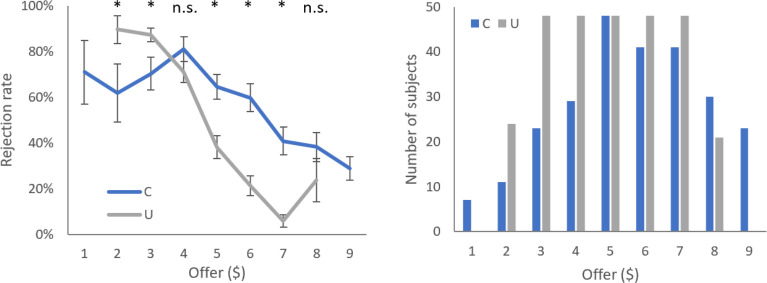

b) Overall rejection rates (mean

C=55.9%, mean

U=58.1%, t(40.76)=–0.33, p=0.74) or (

c) any of the binned rejection rates were not significantly different between the two conditions (paired t

-test; low ($1–3): mean

C=76%, mean

U=81%, t(12)=1.54, p=0.15; middle ($4–6): mean

C=64%, mean

U=56%, t(26)=1.74, p=0.09; high ($7–9): mean

C=39%, mean

U=29%, t(19)=0.80, p=0.44). (

d, e) The DIC scores showed a similar pattern to the social task, with the elbow point at the 2-step FT model for both conditions. Paired t-tests confirmed that the 2-step model’s DIC scores were significantly lower than the 0-step model (Controllable: t(26)=–3.16, p<0.01; Uncontrollable: t(26)=–2.38, p<0.05) and the 1-step model (Controllable: t(26)=–3.02, p<0.01; Uncontrollable: t(26)=–2.31, p<0.05), whereas the DIC scores were not significantly different between the 2-step model and the 3-step model (Controllable: t(26)=–1.23, p=0.23; Uncontrollable: t(26)=0.20, p=0.84) or the 4-step model (Controllable: t(26)=0.68, p=0.50; Uncontrollable: t(26)=–0.13, p=0.90). (

f) Expected influence was significantly higher for the Controllable than the Uncontrollable condition (mean

C=1.31, mean

U=0.75, t(26)=2.54, p<0.05). (

g) In contrast to the social task, self-reported controllability was not different between the two conditions when individuals played the game with a computer (mean

C=62.7, mean

U=56.9, t(25)=0.78, p=0.44). (

h) To unpack the norm prediction error×social interaction effect in

Supplementary file 1a, we used the regression coefficients from the original mixed-effect regression (‘emotion rating~ offer+norm prediction error+condition+task+task*(offer+norm prediction error+condition)+(1+offer+norm prediction error | subject)’) and calculated the residual, which should be explained by the differential impact of nPE between social and non-social tasks. Correlation coefficients between the residuals and nPE were plotted for each task condition (mean

Social=0.151, mean

Non-social=0.005; SD

Social=0.023, SD

Non-social=0.025). Note that the non-social task was coded as the reference group (0 for the group identifier) in our original regression. This result indicates that the impact of nPE was stronger in the social than in the non-social Computer task. Bars represent the mean of the coefficients and error bars represent the standard deviation. (

i) To unpack the Controllable×social task interaction effect in

Supplementary file 1a, similar to (

h), we used the coefficients from the original mixed-effect regression (‘emotion rating~ offer+norm prediction error+condition+task+task*(offer+norm prediction error+condition)+(1+offer+norm prediction error | subject)’) and calculated the residual by each condition and task as shown in the figure (mean

Social(C)=–5.00, mean

Social(U)=–0.58, mean

Computer(C)=0.63, mean

Computer(U)=0.00; SEM

Social(C)=0.46, SEM

Social(U)=0.43, SEM

Computer(C)=0.72, SEM

Computer(U)=0.77). Bars represent the mean of the coefficients and error bars represent SEM. Note that the non-social task and the Uncontrollable condition were coded as the reference group (0 for the group identifiers) in the regression. These results show that the emotion ratings were lower in the Controllable social context compared to the non-social as well as the Uncontrollable social context. We speculate that exerting control over other people—compared to not needing to exert control over other people or playing with computer partners—might be more effortful (as shown by our RT results). Intentionally decreasing other people’s portion of money might also induce a sense of guilt. Satterthwaite’s approximation was used for the effective degrees of freedom for t-test with unequal variance. The variance significantly differed for the offer and the overall rejection rates. Error bars and shades represent SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; n.s. indicates not significant. For (

a,

b,

f,

g), each line represents a participant and each bold line represents the mean. DIC, Draper’s Information Criteria; FT, forward thinking.