Abstract

BACKGROUND:

While autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT) has become a common practice for eligible patients in the front-line setting with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), there are limited data regarding trends in autoHCT utilization and associated outcomes.

METHODS:

This study utilized the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research database to evaluate survival outcomes and transplant utilization in adults age ≥ 18 years-old who underwent autoHCT within 12-months of MCL diagnosis between January 2000 and December 2018. The 19-year period from 2000–2018 was divided into 4 separate intervals, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, and 2015–2018, and encompassed 5082 patients. To evaluate transplant utilization patterns, we combined MCL incidence derived from the SEER 21 database with CIBMTR reported autoHCT activity within 12-months of MCL diagnosis. Primary outcomes included overall survival (OS) along with the stem cell transplant utilization rate.

RESULTS:

The cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality at 1-year decreased from 7% in the earliest cohort (2000–2004) to 2% in the latest cohort (2015–2018). Mirroring this trend, OS outcomes continually improved with time, whereby the 3-year OS was 72% in the earliest cohort and improved to 86% in the latest cohort. Additionally, we noted an increase in autoHCT utilization from 2001 to 2018, particularly in patients ≤ 65 years old.

CONCLUSIONS:

This large retrospective analysis highlights utilization trends and autoHCT outcomes in patients with MCL and emphasizes the need to optimize pre- and post-transplant treatment strategies to enhance survival outcomes.

Keywords: Mantle cell lymphoma, Autologous transplantation, Chemoimmunotherapy, Transplantation outcomes, Transplantation utilization

Precis for use in the Table of Contents:

Using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research database, we demonstrate that over time survival for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients undergoing front-line consolidative autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT) has improved, though lymphoma remains the primary cause of death. AutoHCT as front-line consolidation appears to be utilized in only a minority of MCL patients.

INTRODUCTION:

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon subtype of B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) characterized by the t(11:14) chromosomal translocation which results in dysregulation and overexpression of cyclin D1.1, 2 Compared to other B-NHL subtypes, MCL has a less favorable prognosis, especially for patients harboring high-risk features such as TP53 alterations, blastoid or pleomorphic histology, an elevated Ki-67 proliferative index, or a high-risk MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score.3–6 The treatment of MCL has evolved through the years based on a better understanding of disease biology, patient selection, and optimal treatment regimens. Specifically, the introduction of intensive induction chemotherapy, the incorporation of rituximab, and the advent of novel agents have altered the therapeutic landscape.7–12

In MCL, front-line treatment selection is heavily influenced by patient age, comorbidities, and fitness for intensive therapy. Rituximab and cytarabine containing induction regimens followed by high-dose conditioning therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT) has emerged as a common practice in young (< 65 years) and fit patients with newly diagnosed MCL based on data demonstrating prolonged progression-free survival (PFS).7, 8, 13, 14

While front-line consolidative autoHCT is a common practice at many centers, there remains limited longitudinal data regarding survival outcomes and utilization rates in patients undergoing this treatment approach in the United States (US). To address this knowledge gap, we used the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) registry to evaluate outcomes of MCL patients undergoing autoHCT within 12-months of diagnosis. We hypothesized that over time the survival of MCL patients undergoing autoHCT as front-line consolidation has improved.

METHODS:

Data source:

The CIBMTR is a working group of more than 380 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed HCT data to a statistical center housed at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW), Milwaukee. Participating centers report all HCTs consecutively, and compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Data quality is ensured through computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and onsite audits of participating centers. Observational studies by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with federal regulations related to the protection of human research subjects. Patients provided written informed consent for research. The institutional review boards of the MCW and the National Marrow Donor Program approved this study.

The CIBMTR collects data at 2 levels: Transplant Essential Data (TED) and Comprehensive Report Form (CRF) data. TED-data include age, sex, disease type, date of diagnosis, pre-HCT disease stage and chemotherapy responsiveness, conditioning regimen, graft type, post-HCT disease progression and survival, development of a new malignant neoplasm(s), and cause of death. All CIBMTR centers contribute TED-data. The CIBMTR uses a weighted randomization scheme to select a subset of patients for CRF reporting with more details about disease and pre- and post-HCT clinical information. Both TED- and CRF-level data are collected before HCT, at 100 days, and 6 months post-HCT, and annually thereafter or until death. Data for the current analysis were retrieved from CIBMTR transplant (TED and CRF) report forms.

Patients:

This retrospective analysis included adults age ≥ 18 years-old with a diagnosis of MCL who underwent an autoHCT within 12-months of diagnosis between January 2000 and December 2018, in the US. To determine if survival has improved over time, patients were grouped into 4 time periods: 2000 through 2004 (reference group), 2005 through 2009, 2010 through 2014, and 2015 through 2018.

The incidence of MCL was obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the US National Cancer Institute. SEER data comprises population-based cancer registries covering approximately 34.6% of the US population. We utilized the SEER 21 database, which includes patients diagnosed from 2000–2017. We subsequently calculated incidence rates per 100,000 persons for the years 2001–2017 using US population estimates (SEER*Stat, version 8.3.8). We combined MCL incidence derived from the SEER program with transplantation activity for autoHCT within 12-months of MCL diagnosis reported to the CIBMTR for the period of 2001 to 2017 to assess the transplant utilization.

Study Endpoints and Definitions:

Disease response prior to autoHCT was assessed using the International Working Group criteria.15, 16 Primary outcomes included overall survival (OS) along with the stem cell transplant utilization rate (STUR). Secondary outcomes included PFS, relapse/progression, and non-relapse mortality (NRM). NRM was defined as death from any cause without evidence of MCL progression or relapse; relapse/progression was considered a competing risk. Relapse/progression was defined as progressive lymphoma after autoHCT, or lymphoma recurrence after a CR; NRM was considered a competing risk. PFS was defined as survival without death or relapse/progression. OS was defined as the time from autoHCT until death. All data were censored at date of last follow-up.

Statistical Analyses:

The STUR provided an estimate of transplantation rates and was defined as autoHCT within 12-months of diagnosis each year divided by newly diagnosed MCL patients for that year (US population yearly * SEER incidence rate). The number of autoHCT each year for MCL was calculated as the number of first autoHCT reported to the CIBMTR divided by the CIBMTR capture rate. The estimated CIBMTR capture rate from 2000–2008 was 75% and increased to 80% from 2009 to 2018.

Baseline patient, disease, and autoHCT characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. PFS and OS probabilities were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimates and comparison of survival curves was performed using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidences and Gray’s test of relapse/progressions and NRM were calculated to accommodate for competing risks. One-, three-, and five-year probabilities with 95% CIs and P-values were reported. A Cox proportional hazards model was performed to identify prognostic factors via forward stepwise variable selection with the categorical year of transplant as the main effect. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining a time-varying effect for each variable. Interactions between year of transplant and significant factors were examined. Center effect was significant using the score test of homogeneity for OS, PFS, and relapse/progression; therefore, the marginal cox model was chosen to make adjustments for center effect in these instances.17, 18 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and covariates with a P <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS:

Baseline Characteristics:

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The study included 5082 patients who underwent a first autoHCT for MCL within 12-months of diagnosis between 2000 and 2018. Of the 5082 cases, 4381 (86%) were reported through TED level data. There were 331 patients transplanted between 2000 and 2004, 1283 patients transplanted between 2005 and 2009, 1922 patients transplanted between 2010 and 2014, and 1546 patients transplanted between 2015 and 2018. Throughout the course of the study, autoHCT recipients were largely of male gender and transplanted at a median age of 57–60 years. Notable differences among the four cohorts included the incidence a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥ 90, remission status at the time of autoHCT, and conditioning regimen utilized. Compared with the earliest cohort (2000–2004), patients in subsequent cohorts were more likely to have a preserved KPS of ≥ 90 at the time of autoHCT. Similarly, patients were more likely to be in a complete remission (CR) at the time of autoHCT in the three later time periods. BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) conditioning therapy was increasingly utilized over time mirroring a decrease in utilization of total body irradiation (TBI)-based conditioning regimens. The application of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) at any point following autoHCT relapse remained relatively stable between 2000 and 2014 with a lower utilization in the more recent cohort (2015–2018), though an accurate assessment of alloHCT utilization patterns in the recent cohort is limited by a short median follow-up of only 24 months.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| 2000–2004 | 2005–2009 | 2010–2014 | 2015–2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| No. of patients | 331 | 1283 | 1922 | 1546 |

|

| ||||

| No. of centers | 99 | 126 | 136 | 130 |

|

| ||||

| Age at diagnosis, years - n (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Median (range) | 57 (32–73) | 59 (23–78) | 59 (23–78) | 59 (24–78) |

|

| ||||

| < 65 | 285 (86) | 984 (77) | 1493 (78) | 1170 (76) |

|

| ||||

| Age at HCT, years - n (%) | ||||

| Median (range) | 57 (32–73) | 59 (24–78) | 60 (23–78) | 60 (24–78) |

| 60–69 | 103 (31) | 496 (39) | 833 (43) | 662 (43) |

| ≥ 70 | 13 (4) | 102 (8) | 124 (6) | 116 (8) |

|

| ||||

| Male gender - n (%) | 249 (75) | 987 (77) | 1450 (75) | 1172 (76) |

|

| ||||

| KPS - n (%) | ||||

| ≥ 90 | 21 (6) | 438 (34) | 1342 (70) | 1032 (67) |

| < 90 | 238 (72) | 571 (45) | 541 (28) | 502 (32) |

| Missing | 72 (22) | 274 (21) | 39 (2) | 12 (1) |

|

| ||||

| Race - n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 310 (94) | 1200 (94) | 1798 (94) | 1404 (91) |

| African American | 6 (2) | 33 (3) | 63 (3) | 56 (4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (1) | 12 (1) | 22 (1) | 28 (2) |

| Native American | 0 | 1 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 8 (1) |

| Other1 | 6 (2) | 17 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| More than one race | 0 | 2 (<1) | 6 (<1) | 6 (<1) |

| Missing | 6 (2) | 18 (1) | 29 (2) | 44 (3) |

|

| ||||

| Remission status at autoHCT - n (%) | ||||

| Complete remission | 209 (63) | 941 (73) | 1528 (80) | 1338 (87) |

| Partial remission | 73 (22) | 268 (21) | 371 (19) | 195 (13) |

| Resistant | 8 (2) | 20 (2) | 18 (1) | 12 (1) |

| Untreated/missing | 41 (13) | 54 (4) | 5 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Graft type - n (%) | ||||

| Bone marrow | 1 (<1) | 14 (1) | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| Peripheral blood | 320 (97) | 1265 (99) | 1920 (100) | 1546 (100) |

| Missing | 10 (3) | 4 (<1) | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Conditioning regimen - n (%) | ||||

| BEAM | 23 (7) | 354 (28) | 1252 (65) | 1274 (82) |

| CBV | 69 (21) | 299 (23) | 372 (19) | 96 (6) |

| TBI-based | 75 (23) | 116 (9) | 92 (5) | 19 (1) |

| Others | 119 (36) | 396 (31) | 185 (10) | 144 (9) |

| Missing | 45 (14) | 118 (9) | 21 (1) | 13 (1) |

|

| ||||

| AlloHCT after relapse - n (%) | ||||

| No relapse | 185 (56) | 573 (45) | 995 (52) | 1237 (80) |

| No | 114 (34) | 588 (46) | 751 (39) | 275 (18) |

| Yes | 32 (10) | 122 (10) | 176 (9) | 34 (2) |

|

| ||||

| Rituximab in maintenance – n (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| No | 88 (27) | 215 (17) | 164 (9) | 70 (5) |

|

| ||||

| Yes | 3 (1) | 37 (3) | 33 (2) | 71 (5) |

|

| ||||

| Not available at TED level | 240 (73) | 1031 (80) | 1725 (90) | 1405 (91) |

|

| ||||

| Median overall survival, months | 89 | 137 | NR | NR |

|

| ||||

| Median follow-up of survivors, months (range) | 168 (3–217) | 120 (3–178) | 72 (3–116) | 24 (3–55) |

Abbreviations: HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant; KPS = Karnofsky performance status; BEAM = carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; CBV = cyclophosphamide, carmustine, etoposide; TBI = total body irradiation; AlloHCT = allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; TED = transplant essential data; NR = not reached

Race: Other: 2000–2004: 5 Hispanic, race NOS; 1 other race NOS. 2005–2009: 4 Hispanic, race NOS; 13 other race NOS.

Non-relapse Mortality and Relapse/Progression:

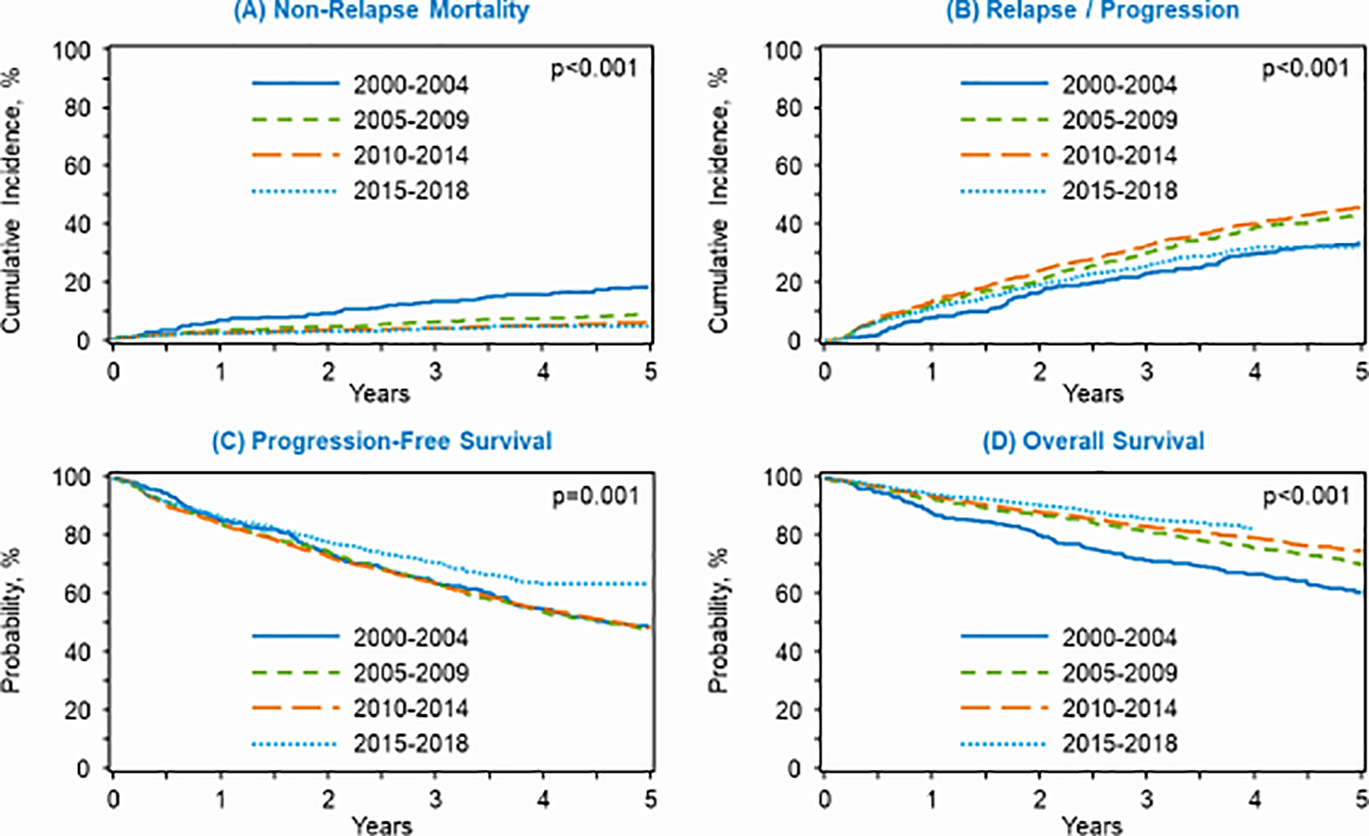

On univariate analysis, the cumulative incidence of NRM for all transplanted patients decreased over time (Table 2). During the earliest cohort (2000–2004) NRM at 1 and 5 years went from 7% and 18%, respectively, to 2% and 5% in the 2015 to 2018 cohort. On multivariate analysis (MVA), a significantly lower NRM risk was noted for autoHCT performed during 2005–2009 (Hazard ratio [HR] 0.51; 95% CI, 0.39–0.67, P <0.0001), 2010–2014 (HR 0.52; 95% CI, 0.37–0.73, P = 0.0001), and 2015–2018 (HR 0.45; 95% CI, 0.29–0.69, P = 0.0003) when compared to 2000–2004 (Table 3, Figure 1A).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of outcomes in patients undergoing first autoHCT for MCL

| 2000–2004 (N =331) | 2005–2009 (N =1283) | 2010–2014 (N =1922) | 2015–2018 (N = 1546) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Outcomes | N | Probability, % (95% CI) | N | Probability, % (95% CI) | N | Probability, % (95% CI) | N | Probability, % (95% CI) | P Value |

|

| |||||||||

| NRM | 310 | 1267 | 1906 | 1540 | <0.001 | ||||

| 1-year | 7 (4–10) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.012 | ||||

| 3-year | 13 (10–17) | 6 (5–7) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 | ||||

| 5-year | 18 (14–23) | 9 (7–10) | 6 (5–7) | 5 (3–6) | <0.001 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Relapse/progression | 310 | 1267 | 1906 | 1540 | <0.001 | ||||

| 1-year | 8 (5–11) | 12 (11–14) | 13 (12–15) | 11 (10–13) | 0.013 | ||||

| 3-year | 23 (19–28) | 30 (28–33) | 32 (30–35) | 26 (23–28) | <0.001 | ||||

| 5-year | 34 (28–39) | 44 (41–46) | 46 (44–48) | 32 (28–36) | <0.001 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| PFS | 310 | 1267 | 1906 | 1540 | 0.001 | ||||

| 1-year | 85 (81–89) | 85 (83–87) | 84 (83–86) | 87 (85–88) | 0.239 | ||||

| 3-year | 64 (58–69) | 64 (61–67) | 64 (62–66) | 71 (68–74) | <0.001 | ||||

| 5-year | 48 (43–54) | 48 (45–51) | 48 (46–51) | NE | 0.944 | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| OS | 331 | 1283 | 1922 | 1546 | <0.001 | ||||

| 1-year | 88 (84–92) | 93 (92–94) | 94 (93–95) | 95 (93–96) | 0.006 | ||||

| 3-year | 72 (67–77) | 82 (79–84) | 84 (82–85) | 86 (84–88) | <0.001 | ||||

| 5-year | 61 (55–66) | 70 (68–73) | 75 (73–77) | NE | <0.001 | ||||

Abbreviations: NRM = non-relapse mortality; PFS = progression-free survival; NE = not evaluable; OS = overall survival.

Table 3.

Main Effect of Multivariable Regression Analysis

| N | HR | Prob (95% CI) | P | Overall P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| NRM | |||||

| Year of Transplant | |||||

| 2000–2004 | 310 | 1.00 | <.0001 | ||

| 2005–2009 | 1267 | 0.51 | 0.39–0.67 | <.0001 | |

| 2010–2014 | 1906 | 0.52 | 0.37–0.73 | 0.0001 | |

| 2015–2018 | 1540 | 0.45 | 0.29–0.69 | 0.0003 | |

| Relapse/Progression | |||||

| Year of Transplant | |||||

| 2000–2004 | 310 | 1 | <.0001 | ||

| 2005–2009 | 1267 | 1.40 | 1.16–1.70 | 0.0006 | |

| 2010–2014 | 1906 | 1.51 | 1.25–1.84 | <.0001 | |

| 2015–2018 | 1540 | 1.23 | 0.99–1.53 | 0.0623 | |

| Relapse/progression adjusted for significant covariates: Age, sex, disease status | |||||

| PFS | |||||

| Year of Transplant | |||||

| 2000–2004 | 310 | 1.00 | 0.0182 | ||

| 2005–2009 | 1267 | 1.04 | 0.89–1.21 | 0.6344 | |

| 2010–2014 | 1906 | 1.07 | 0.92–1.25 | 0.3702 | |

| 2015–2018 | 1540 | 0.88 | 0.73–1.05 | 0.1551 | |

| PFS adjusted for significant covariates: Age, sex, disease status | |||||

| Overall Survival | |||||

| Year of Transplant | |||||

| 2000–2004 | 331 | 1.00 | <.0001 | ||

| 2005–2009 | 1283 | 0.74 | 0.62–0.88 | 0.0006 | |

| 2010–2014 | 1922 | 0.68 | 0.57–0.82 | <.0001 | |

| 2015–2018 | 1546 | 0.58 | 0.46–0.73 | <.0001 | |

| OS adjusted for significant covariates: Age, KPS, disease status | |||||

Abbreviations: NRM = non-relapse mortality; PFS = progression-free survival; OS = overall survival; KPS = Karnofsky performance status.

Figure 1:

Autologous hematopoietic cell transplant outcomes by era of transplant for (A) non-relapse mortality, (B) relapse/progression, (C) progression-free survival, and (D) overall survival.

The cumulative incidence of relapse/progression at 5 years was 34% from 2000–2004 and increased during the period of 2005–2009 (44%) and 2010–2014 (46%) prior to decreasing again during 2015–2018 (32%) (Table 2). On MVA, autoHCT during 2005–2009 (HR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.7, P = 0.0006) and 2010–2014 (HR 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.8, P <0.0001) was associated with an increased risk of relapse/progression compared 2000–2004 (Table 3, Figure 1B). Advanced age (≥ 60 years) at autoHCT was associated with a modestly increased risk (HR 1.2) of relapse/progression compared to patients < 60 years. Relative to patients in CR, those undergoing autoHCT in a PR (HR 2.0; 95% CI, 1.8–2.3, P <0.0001) or with resistant disease (HR 2.5; 95% CI, 1.7–3.6, P <0.0001) were at a significantly higher risk for relapse/progression. Additional details regarding significant covariates in the MVA for relapse/progression are delineated in Supporting Table 1.

PFS and OS:

On univariate analysis, 3-year PFS remained stable at 64% within the first three time periods and appeared to improve in the recent cohort (2015–2018) to 71% (P <0.001) (Table 2). On MVA, after adjusting for age, sex, and disease status at autoHCT, the era of transplantation was not independently predictive of PFS (Table 3, Figure 1C). Throughout the study, OS improved with time; specifically, the 3-year OS was 72% in the 2000–2004 era and increased to a peak of 86% in the period from 2015 to 2018 (Table 2). On MVA after adjusting for age, KPS, and disease status, autoHCT performed during 2005–2009 (HR 0.74; 95% CI, 0.62–0.88, P = 0.0006), 2010–2014 (HR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.57–0.82, P < 0.0001), and 2015–2018 (HR 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46–0.73, P < 0.0001) was associated with a lower mortality risk when compared to 2000–2004 (Table 3, Figure 1D). Furthermore, MVA suggests that advanced age (≥ 60 years), impaired KPS performance status (< 90%), and achieving a partial remission or having resistant disease prior to autoHCT were all independently predictive of an increased risk of mortality following transplantation (Supporting Table 1).

Causes of Death:

The primary cause of death in all cohorts was relapsed/progressive MCL, comprising 48% in 2000–2004, 55% in 2005–2009, 59% in 2010–2014, and 64% in 2015–2018. (Supporting Table 2) Common causes of death additionally included other HCT related causes, secondary malignancy, along with organ failure.

Stem Cell Transplant Utilization Rates:

AutoHCT utilization was evaluated in patients ≤ 65 years old, a population commonly considered for front-line consolidative autoHCT. For the analysis, the incidence of MCL was abstracted from the SEER database for the years 2001 to 2017 and the STUR was calculated. Based on data from Epperla et al., the incidence of MCL has increased through time from 0.71 per 100,000 from 2000–2006 to 0.8 from 2007–2013.19 In patients ≤ 65 years old, autoHCT utilization steadily increased from 5.4% in 2001 to a peak of 22.3% in 2013 followed by a slight decrease to 18.1% in 2017. When examining utilization of autoHCT in patients ≤ 65 years old based on sex, there was a lower utilization seen in female patients during the course of the study (Table 4). STUR data for the entire study population are delineated in Supporting Table 3.

Table 4.

Utilization rates for MCL patients age 65 years or younger diagnosed 2001–2017 based on CIBMTR reporting

| Male and female | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Utilization rate, % (95% CI) | Utilization rate, % (95% CI) | Utilization rate, % (95% CI) |

| 2001 | 5.4% (5.0–5.8) | 6.1% (5.6–6.6) | 3.6% (3.2–4.1) |

| 2002 | 9.9% (9.3–10.7) | 8.7% (8.0–9.4) | 14.9% (12.3–16.6) |

| 2003 | 9.4% (8.8–10.1) | 10.3% (9.5–11.1) | 6.5% (5.3–7.3) |

| 2004 | 10.2% (9.6–10.9) | 10.5% (9.6–11.3) | 9.7% (8.6–11.2) |

| 2005 | 11.4% (10.8–12.4) | 12.7% (11.7–13.6) | 8.5% (7.5–9.8) |

| 2006 | 13.1% (12.3–13.9) | 12.9% (12.0–14.0) | 13.9% (11.9–15.9) |

| 2007 | 13.0% (12.3–14.1) | 13.7% (12.7–14.8) | 11.5% (10.3–13.7) |

| 2008 | 14.1% (13.4–15.3) | 14.2% (13.3–15.4) | 14.8% (12.8–16.9) |

| 2009 | 19.6% (18.6–21.2) | 20.7% (19.3–22.4) | 17.6% (15.2–20.0) |

| 2010 | 17.3% (16.4–18.6) | 17.9% (16.7–19.3) | 16.2% (14.3–18.0) |

| 2011 | 21.8% (20.7–23.5) | 21.2% (19.8–22.9) | 24.3% (21.1–27.3) |

| 2012 | 19.8% (18.9–20.9) | 20.9% (19.6–22.5) | 16.7% (15.2–19.3) |

| 2013 | 22.3% (21.2–24.0) | 22.0% (20.6–23.6) | 23.9% (21.0–26.7) |

| 2014 | 19.4% (18.5–20.5) | 20.1% (18.7–21.4) | 18.2% (16.1–20.2) |

| 2015 | 19.3% (18.4–20.7) | 20.5% (19.2–22.0) | 16.4% (14.5–18.2) |

| 2016 | 19.9% (18.6–21.0) | 20.4% (19.5–22.4) | 17.1% (15.5–19.1) |

| 2017 | 18.1% (17.0–19.1) | 17.5% (16.3–18.8) | 19.9% (17.5–22.2) |

DISCUSSION:

We evaluated trends in survival outcomes in 5082 patients with MCL who underwent autoHCT within 12-months of diagnosis over a 19-year period. When comparing across time periods, there has been a continual improvement in OS since 2000, most notably in the recent cohort (2015–2018) where 3-year survival exceeds 80%. This OS trend was most pronounced in patients of younger age (< 60 years), preserved KPS (≥ 90%) and in those achieving a CR prior to autoHCT. This improvement in OS is largely driven by a decline in NRM, likely related to improvements in supportive care measures along with refinements in patient selection for autoHCT. Similarly, the shift from TBI-based conditioning regimens towards BEAM conditioning therapy throughout the study period may have additionally influenced this trend.

The cumulative incidence of relapse/progression at 5-years was 34% from 2000–2004 and increased in the two subsequent time periods to approximately 45%, prior to improving to 32% in the recent cohort. This trend may be explained by the high incidence of NRM in the 2000–2004 cohort which resulted in fewer patients being at risk for relapse/progression. In this analysis, 4381 of the 5082 (86%) cases were reported with TED level data and therefore induction and maintenance therapies were not adequately captured. We speculate that more uniform adoption of novel therapeutics, including the use of rituximab in both the front-line setting and as maintenance therapy following autoHCT, may account for the reduction in relapse/progression seen in the recent cohort (2015–2018), though we cannot exclude other factors.7–9, 20–24 PFS largely remained stable during the course of the study, suggesting that the increased OS may also be related to the application of novel targeted agents in the post-autoHCT salvage setting including bortezomib, lenalidomide, and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor therapy.10–12 Collectively, these data support research efforts focused on optimizing both pre- and post-transplantation strategies to further improve survival outcomes.

The incidence of MCL has increased in the past two decades, mirrored by an increase in autoHCT utilization.19, 25 The increased application of autoHCT as front-line consolidation in MCL coincides with the publication of clinical trials and retrospective analyses establishing the importance of high-dose conditioning therapy and autoHCT in this disease.7, 8, 26–28 During the study period, autoHCT utilization rose in both male and female patients and specifically in those ≤ 65 years of age. Our data show that autoHCT was less frequently applied in female patients, consistent with previously published data.29 This trend may be related to referral patterns, though the underlying reasons are unclear and deserve a more comprehensive evaluation. Despite evidence-based national practice guidelines recommending MCL patients be evaluated at a transplant center, the utilization of autoHCT remains at < 20% in recent years.30 Reasons for this relatively low utilization are varied and unfortunately our analysis does not adequately address root causes. We speculate that the decline in autoHCT utilization coincides with the regulatory approval of multiple novel agents with encouraging activity in the salvage setting. Additionally, a shift in practice patterns including the application of maintenance rituximab therapy in lieu of autoHCT consolidation may explain this trend. In the upcoming years, we reason that the utilization of autoHCT may continue to decline due to the broader adoption of cellular therapy-based treatments (e.g. brexucabtagene autoleucel).

This analysis has several limitations. Inherent with large retrospective registry studies, potential patient-selection biases and center-specific transplantation practices cannot be excluded. For the analysis, patients were grouped into four cohorts in order to examine survival trends over time. This grouping was arbitrary and not intended to reflect changes in practice patterns or pharmacologic advancements. Additionally, baseline disease characteristics such as MIPI score and the presence of TP53 alterations were not collected in the CIBMTR database during the study period, limiting our ability to assess the impact of these features on outcomes. While the utilization of front-line consolidative autoHCT in MCL and the survival outcomes following have improved, it must be recognized that these data are abstracted exclusively from a transplantation registry with no non-transplant comparator. Consequently, the true proportion of MCL patients who may be candidates for autoHCT is not known. Furthermore, this dataset does not specifically address the merits of autoHCT as front-line consolidation in this population, though recently published data suggest that a consolidative autoHCT is associated with improved PFS.31

In conclusion, our analysis confirms a continuous improvement in OS over time for MCL patients who undergo front-line autoHCT as consolidation in the US. This study also highlights that the utilization of autoHCT in this population has increased with time but still constitutes only a minority of all patients with MCL. While front-line autoHCT in MCL yields excellent PFS and OS, disease relapse/progression remains the most common cause of death. Despite the inherent limitations within this retrospective analysis, these data may help to serve as a basis against which future therapeutic approaches are compared.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Survival has improved for MCL patients undergoing front-line consolidative autoHCT, though lymphoma remains the primary cause of death.

AutoHCT as front-line consolidation appears to be underutilized in MCL.

FUNDING SUPPORT:

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); HHSH250201700006C from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014-20-1-2705 and N00014-20-1-2832 from the Office of Naval Research; Additional federal support is provided by R01AI128775, R01HL130388, and BARDA. Support is also provided by Be the Match Foundation, the Medical College of Wisconsin the National Marrow Donor Program, and from the following commercial entities: Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adienne SA; Allovir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Angiocrine Bioscience; Astellas Pharma US; bluebird bio, Inc.; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; Celgene Corp.; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.; ExcellThera; Fate Therapeutics; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Genentech Inc; Incyte Corporation; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin; Legend Biotech; Magenta Therapeutics; Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Oncoimmune, Inc.; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Pharmacyclics, LLC; Sanofi Genzyme; Stemcyte; Takeda Pharma; Vor Biopharma; Xenikos BV. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES:

Peter A. Riedell reports Research Support/Funding: Celgene/BMS, Kite Pharma, Inc./Gilead, MorphoSys, Calibr, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Speaker’s Bureau: Kite Pharma, Inc./Gilead and Bayer; Consultancy on advisory boards: Verastem Oncology, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Celgene/BMS, BeiGene, Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Bayer. Honoraria: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Mehdi Hamadani reports Research Support/Funding: Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; Astellas Pharma. Consultancy: Incyte Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Celgene Corporation; Pharmacyclics, Magenta Therapeutics, Omeros, AbGenomics, Verastem, TeneoBio. Speaker’s Bureau: Sanofi Genzyme, AstraZeneca.

Frederick Locke reports Research Support/Funding: Kite, a Gilead Company; Scientific Advisor: Allogene, Amgen, Bluebird Bio, BMS/Celgene, Calibr, Celgene, GammaDelta Therapeutics, Iovance, Kite/Gilead, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Wugen; Consultancy: Cellular Biomedicine Group, Cowen Consulting, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG), EcoR1, Emerging Therapies.

Claudio G. Brunstein reports Research support: Nant, BlueRock, Fate Therapeutics. Consulting: Allovir.

Taiga Nishihori reports: Research support: Karyopharm, Novartis.

Mohamed A. Kharfan-Dabaja reports Consultancy: Daiichi Sankyo, Pharmacyclics.

Alex Herrera reports Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Seattle Genetics, Karyopharm. Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), Merck (Inst), Pharmacyclics (Inst), Seattle Genetics (Inst), ADCT Therapeutics (Inst). Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Craig S. Sauter reports research support/funding: Juno Therapeutics; Celgene; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Precision Biosciences; Sanofi-Genzyme. Consultancy on advisory boards: Juno Therapeutics; Sanofi-Genzyme; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals; Novartis; Genmab; Precision Biosciences; Kite - A Gilead Company; Celgene; Gamida Cell; Karyopharm Therapeutics; GlaxoSmithKline.

Following authors report no conflicts of interest: Guru Subramanian Guru Murthy, Patrick J. Stiff, Reid Merryman, Attaphol Pawarode and Sonali Smith.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol. August 1998;16(8):2780–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKay P, Leach M, Jackson R, Cook G, Rule S. Guidelines for the investigation and management of mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. November 2012;159(4):405–26. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. October 26 2017;130(17):1903–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-779736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha R, Bhatt VR, Guru Murthy GS, Armitage JO. Clinicopathologic features and management of blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2015;56(10):2759–67. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1026902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyling M, Klapper W, Rule S. Blastoid and pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma: still a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge! Blood. December 27 2018;132(26):2722–2729. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-737502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. Prognostic Value of Ki-67 Index, Cytology, and Growth Pattern in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma: Results From Randomized Trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. April 20 2016;34(12):1386–94. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.63.8387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. October 1 2008;112(7):2687–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delarue R, Haioun C, Ribrag V, et al. CHOP and DHAP plus rituximab followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood. January 3 2013;121(1):48–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-370320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol. March 20 2005;23(9):1984–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. October 20 2006;24(30):4867–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. J Clin Oncol. October 10 2013;31(29):3688–95. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.49.2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. The New England journal of medicine. August 8 2013;369(6):507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damon LE, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for untreated patients with mantle-cell lymphoma: CALGB 59909. J Clin Oncol. December 20 2009;27(36):6101–8. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.22.2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenske TS, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al. Autologous or reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chemotherapy-sensitive mantle-cell lymphoma: analysis of transplantation timing and modality. J Clin Oncol. February 1 2014;32(4):273–81. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.49.2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. February 10 2007;25(5):579–86. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.09.2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. September 20 2014;32(27):3059–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commenges D, Andersen PK. Score test of homogeneity for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 1995;1(2):145–56; discussion 157–9. doi: 10.1007/bf00985764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee EW, Wei LJ, Amato DA, Leurgans S. Cox-Type Regression Analysis for Large Numbers of Small Groups of Correlated Failure Time Observations. In: Klein JP, Goel PK, eds. Survival Analysis: State of the Art. Springer Netherlands; 1992:237–247. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epperla N, Hamadani M, Fenske TS, Costa LJ. Incidence and survival trends in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. June 2018;181(5):703–706. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. The New England journal of medicine. September 28 2017;377(13):1250–1260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim SH, Esler WV, Periman PO, Beggs D, Zhang Y, Townsend M. R-CHOP followed by consolidative autologous stem cell transplant and low dose rituxan maintenance therapy for advanced mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. July 2008;142(3):482–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietrich S, Weidle J, Rieger M, et al. Rituximab maintenance therapy after autologous stem cell transplantation prolongs progression-free survival in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Leukemia. March 2014;28(3):708–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graf SA, Stevenson PA, Holmberg LA, et al. Maintenance rituximab after autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. November 2015;26(11):2323–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanate AS, Kumar A, Dreger P, et al. Maintenance Therapies for Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas After Autologous Transplantation: A Consensus Project of ASBMT, CIBMTR, and the Lymphoma Working Party of EBMT. JAMA Oncol. May 1 2019;5(5):715–722. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y, Wang H, Fang W, et al. Incidence trends of mantle cell lymphoma in the United States between 1992 and 2004. Cancer. 2008;113(4):791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vigouroux S, Gaillard F, Moreau P, Harousseau JL, Milpied N. High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation in first response in mantle cell lymphoma. Haematologica. November 2005;90(11):1580–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tam CS, Bassett R, Ledesma C, et al. Mature results of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center risk-adapted transplantation strategy in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. April 30 2009;113(18):4144–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, et al. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progression-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood. April 1 2005;105(7):2677–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshua TV, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, et al. Access to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: effect of race and sex. Cancer. July 15 2010;116(14):3469–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Abramson JS, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 3.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. June 1 2019;17(6):650–661. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerson JN, Handorf E, Villa D, et al. Survival Outcomes of Younger Patients With Mantle Cell Lymphoma Treated in the Rituximab Era. J Clin Oncol. February 20 2019;37(6):471–480. doi: 10.1200/jco.18.00690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.