Figure S7.

Nucleotide-dependent interactions between STAG1, NIPBL, and cohesin domains, related to Figure 7

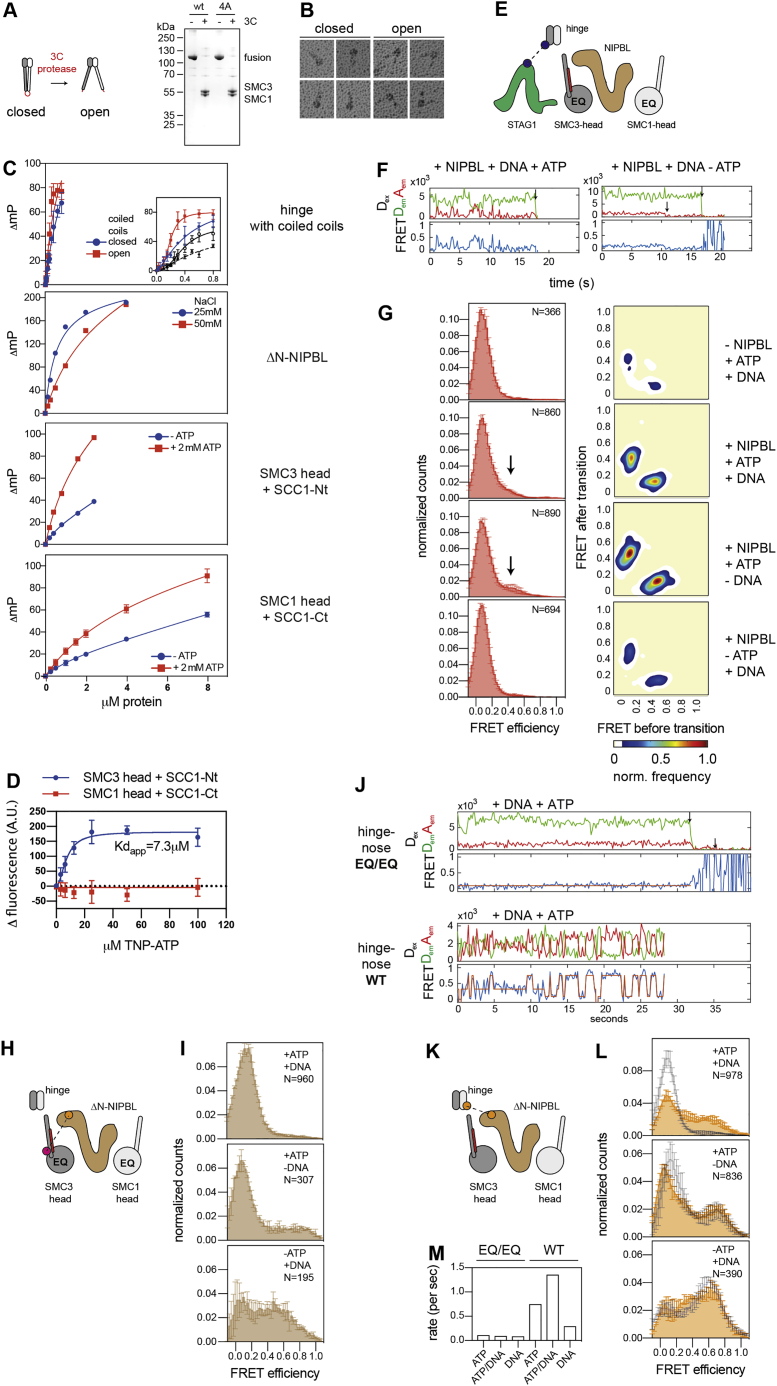

A.) Design and purity of a hinge construct containing the upper coiled coils. The coiled coils emanate from the hinge up until the elbow region and are directly fused to one another with a peptide linker that can be cleaved by 3C-protease. In the uncleaved form, the upper coiled coils are in a closed, but upon cleavage in an open conformation, thus mimicking the rod and ring conformations observed in cohesin.

B.) Rotary shadowing EM images of hinge constructs as in (A), before and after cleavage of the peptide linker (‘closed’ and ‘open’, respectively).

C.) Affinities of different cohesin domains and ΔN-NIPBL to DNA as measured by fluorescence polarization. Proteins were incubated at increasing concentrations with a 75 bp fluorescine-labeled DNA probe under the indicated conditions. DNA binding was monitored by measuring the change in polarization (in milli-polarization units, ‘mP’) of the DNA probe upon protein binding. For the hinge containing short coiled coils, the inlet shows an expanded view of the binding data in the low concentration range and binding data for a construct containing the hinge4A mutations in the closed (black interrupted line) and open conformations (black continuous line). For the ATPase heads, experiments were performed in the presence and absence of 2 mM ATP. Note that the presence of ATP increases the apparent affinities of the ATPase heads for DNA. This indicates that nucleotide-dependent conformational changes affect DNA-binding and that the ATPase heads can bind ATP without forming heterodimers.

D.) Binding of TNP-ATP to the ATPase heads. The fluorescence of TNP-ATP was measured at increasing concentrations in the presence and absence of a constant amount of the SMC3 or SMC1 head domains. Plotted is the change in fluorescence due to binding to protein as a function of the concentration of TNP-ATP (three replicates per condition). Note that we could not detect significant binding of TNP-ATP to the SMC1 head using this assay. However, the effect of addition of 2 mM ATP on the DNA-binding affinity of the SMC1 head (C) would indicate that also the SMC1 head binds ATP at high concentrations, which we could not test using TNP-ATP. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the opposite behavior has been observed for the ATPase heads of yeast condensin, in which the SMC2 head (most similar to SMC1) binds ATP with high affinity and binding of ATP to the SMC4 head (most similar to SMC3) could not be detected (Hassler et al., 2019).

E.) Cartoon illustration of the FRET sensor used to detect interactions between STAG1 and the hinge. CohesinEQ/EQ was used in these experiments to compare engaged and disengaged head conformations.

F.) Example smFRET traces of the hinge-STAG1 sensor, showing transient oscillations between low and high FRET states in the presence but not in absence of ATP.

G.) Left column: FRET distributions of STAG1-hinge interactions. Shown are means ± SD of 3 replicates, with exception of –NIPBL/+ATP/+DNA (2 replicates). The total number of molecules analyzed (N) is indicated. Right column: Transition density plots of conditions shown in the first column.

H.) Cartoon illustration of the FRET sensor pair used to measure interactions between the cohesin hinge and the NIPBL nose. The YBBR-tag was positioned on the N terminus of SCC1, which is close to the SMC3 head.

I.) FRET distributions of nose-SMC3 head interactions in the engaged (top), pre-engaged (middle) and apo conformations (bottom). Means and standard deviations from three replicates.

J.) Example smFRET traces of the hinge-nose sensor in cohesinEQ/EQ (top) and wild-type cohesin (bottom) in the presence of ATP and DNA. Note that the ability to hydrolyze ATP allows cohesin to undergo cycles of binding and dissociation between the hinge and the nose of NIPBL.

K.) Cartoon illustration of the hinge-nose sensor in wild-type cohesin.

L.) FRET distributions of the hinge-nose sensor in wild-type cohesin in different nucleotide conditions (orange). Shown are means ± SD (3 replicates). The corresponding distributions recorded for cohesinEQ/EQ (Figure 7) are outlined in black.

M.) Estimated rates of hinge-nose interactions in cohesinEQ/EQ and wild-type cohesin under different conditions. Half times of low and high FRET states were determined by fitting the distribution of their dwell times to single exponential decay curves. The rates were estimated as the inverse sum of the half times of the low and high FRET states.