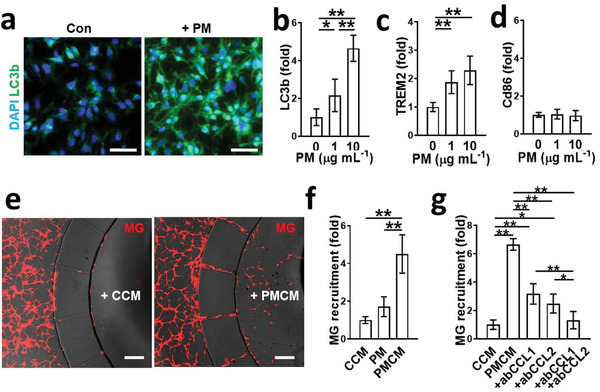

Figure 3.

Microglia migration in response to soluble factors released by PM2.5‐treated neurons and astrocytes. a,b) Increased phagocytic activity of microglia in response to PM2.5. The phagocytic activity was assessed by immunostaining of LC3b. Scale bars represent 50 µm (n = 8). Data represent means ± SD. *, p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; measured by one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni post‐hoc correction for multiple comparisons. c) Activation of microglia serving neuroprotective roles with both sensing and phagocytic activity (TREM2‐positive) by PM2.5. *, p < 0.05 and f > 0.8 versus control (n = 8). d) No detectable transition of M1 type microglia (CD86‐positive) by PM2.5 (n = 8). Data represent means ± SD. **, p < 0.01; measured by one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni post‐hoc correction for multiple comparisons. e) Notable number of microglia (red) were recruited to the central chamber with the conditioned media of Co‐PMB (PMCM) compared to that of Co‐Con (CCM). Scale bars represent 200 µm. f) Quantification of microglia migration. PMCM significantly increased microglia recruitment compared to CCM (n = 4). Data represent means ± SD. **, p < 0.01; measured by one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni post‐hoc correction for multiple comparisons. g) Validation of CCL1 and CCL2 as key chemokines in PMCM to recruit microglia. The addition of blockage antibody either for CCL1 (ab CCL1, 1 µg mL−1) or CCL2 (ab CCL2, 1 µg mL−1) to PMCM significantly reduced the microglia recruitment compared to PMCM (n = 5). The addition of blockage antibodies for both CCL1 and CCL2 completely blocked the microglia recruitment (n = 5). Data represent means ± SD. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; measured by one‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni post‐hoc correction for multiple comparisons.