Highlights

-

•

Pervasive stigma influences when and how Venezuelan migrants are prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination.

-

•

Attention must be paid to terminology defining migrants, which can fuel discrimination and limit healthcare access.

-

•

Migrants must be fully integrated into public health strategies to uphold a rights-based approach to health.

-

•

Full integration of migrants is a matter not just of social justice but a pragmatic strategy to stop pandemic spread.

Keywords: Latin America, COVID-19 vaccine equity, Venezuela, Migrants, South-South migration, Health justice, Critical global health

Abstract

Introduction

The entangled health and economic crises fueled by COVID-19 have exacerbated the challenges facing Venezuelan migrants. There are more than 5.6 million Venezuelan migrants globally and almost 80% reside throughout Latin America. Given the growing number of Venezuelan migrants and COVID-19 vulnerability, this rapid scoping review examined how Venezuelan migrants are considered in Latin American COVID-19 vaccination strategies.

Material and Methods

We conducted a three-phased rapid scoping review of documents published until June 18, 2021: Peer-reviewed literature search yielded 142 results and 13 articles included in analysis; Gray literature screen resulted in 68 publications for full-text review and 37 were included; and official Ministry of Health policies in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru were reviewed. Guided by Latin American Social Medicine (LASM) approach, our analysis situates national COVID-19 vaccination policies within broader understandings of health and disease as affected by social and political conditions.

Results

Results revealed a heterogeneous and shifting policy landscape amid the COVID-19 pandemic which strongly juxtaposed calls to action evidenced in literature. Factors limiting COVID-19 vaccine access included: tensions around terminologies; ambiguous national and regional vaccine policies; and pervasive stigmatization of migrants.

Conclusions

Findings presented underscore the extreme complexity and associated variability of providing access to COVID-19 vaccines for Venezuelan migrants across Latin America. By querying the timely question of how migrants and specifically Venezuelan migrants access vaccinations findings contribute to efforts to both more equitably respond to COVID-19 and prepare for future pandemics in the context of displaced populations. These are intersectional and evolving crises and attention must also be drawn to the magnitude of Venezuelan mass migration and the devastating impact of COVID-19 in the region. Integration of Venezuelan migrants into Latin American vaccination strategies is not only a matter of social justice, but also a pragmatic public health strategy necessary to stop COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The ongoing humanitarian crises in Venezuela have fueled the largest recorded mass migration and forced displacement in Latin American history (Long and Schipani, 2018; Mur, 2018). As of March 5th, 2021, more than 5.6 million people have fled Venezuela due to intensifying political instability and economic crisis following the presidencies of Hugo Chávez (1999–2013) and Nicolás Maduro (2013-present) (XX, 2021a). Once a wealthy nation with the world's largest oil reserves, by 2019 inflation in Venezuela rose by 10 million percent, while an estimated 94% of the population lived in poverty in 2020 (XXX, 2021b, 2021c). Venezuela's hyper-inflammatory economic collapse has resulted in chronic shortages of food, medicine, and other essential goods. Under Maduro's government there has been a rise in state-sanctioned violence, human-rights abuses, and arbitrary detentions, leading many Venezuelans to seek refuge across Latin America and the Caribbean (Page et al., 2019).

Almost 80% of Venezuelans have migrated to neighboring countries, with the more than four million Venezuelans residing in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru driving most of the migration in the region (XXX, 2021b). Far from a migration success story, displaced Venezuelans have documented experiences of stigmatization, xenophobia, and violence (Standley et al., 2020). The unprecedented influx of displaced Venezuelans into neighboring countries has further strained health care and public services in a region devastated by austerity politics and chronically underfunded public healthcare systems. Indeed, given the sociomaterial strain on host countries, popular and political discourse has focused on the deleterious impact of migrants.

COVID-19′s entangled health and economic crises are exacerbating the challenges facing Venezuelan migrants. According to a survey of 2200 Venezuelans in Colombia, Chile, Perú, and Ecuador, 34% were unemployed during the pandemic, 39% shared a dwelling with three or more people, and 33% reported being at risk of eviction (Equilibrium CenDE, 2020). Global evidence suggests that migrants and refugees are at increased vulnerability to COVID-19 acquisition, as well as worse health outcomes for those who contract COVID-19 (Bojorquez et al., 2021). In Brazil, Venezuelans are considered at heightened vulnerability due to poor living conditions, lack of stable employment, and barriers in accessing health services (Standley et al., 2020). Similarly, Venezuelans living in Colombia tend to reside in overcrowded apartments in Bogotá, the epicenter of the pandemic in Colombia (Monshipouri et al., 2020). Moreover, poor health insurance coverage and barriers in accessing health services place Venezuelan migrants at increased risk of serious illness due to COVID-19 (Equilibrium CenDE , 2021a; Chaves-González and Echeverría-Estrada, 2020).

Amid global calls for the inclusion of migrants and refugees in COVID-19 vaccination priority groups, little is known about how Latin American countries are prioritizing COVID-19 vaccination. Yet, due to the barriers in accessing health and social services for Venezuelan migrants coupled with increased vulnerability to COVID-19, there is an urgent need to better understand how national vaccination strategies in Latin America will address migrants, including the growing number of Venezuelan migrants. This rapid scoping review addresses this gap, taking up a Latin American Social Medicine approach to assess the region's sociopolitical context and explore the extent to which Venezuelan migrants are considered in COVID-19 vaccination strategies in Latin America.

2. Material and methods

We conducted a three-phased rapid scoping review (Tricco et al., 2015) assessing how, if at all, Venezuelan migrants are considered in Latin American COVID-19 vaccination strategies. We assessed academic literature, gray literature, and country-level government documents published on or before June 18th 2021. COVID-19 vaccination policies were evaluated in brief for 18 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, while an in-depth review was conducted for the six countries hosting the majority of Venezuelans in the Latin American region (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru). Data extraction was divided by data source with at least one full-text reviewer and data extractor per publication: academic literature [DH]; country-level government policies [ZA-R & KS]; and gray literature [EA]. Throughout the data extraction process, the team met twice weekly to review extraction procedures, utilizing a combination of online platforms for screening and data extraction (Covidence, Google Forms, Zotero, and Excel) and engaging in iterative summative content analysis, reviewing, comparing, discussing, and interpreting data across a six-week period (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005).

The aim of the scoping review was to explore how Venezuelan migrants are considered in COVID-19 vaccination strategies in Latin America, given that Venezuelan migrants are driving migration in the region. Yet, as Venezuelan migrants are often categorized within the broader umbrella categories of migrant, regular and irregular migratory status, the search strategy entailed a close review of text and references and key word searches. These variations in terminologies were salient in the review of government websites and documents which were frequently updated in the three-month review period. Further given the rapidly changing landscape, this scoping review concurrently examined peer-reviewed, gray literature, and governmental policy documents to assess the complexity potentially shaping Venezuelan migrants’ access to COVID-19 vaccines. Inclusion criteria included peer-reviewed, gray literature, and official government documents that addressed COVID-19 vaccine access for Venezuelan migrants in Latin America, and were published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese between January 2020 and June 2021. Further details by search strategy below.

Academic literature: The search strategy was created in consultation with a health sciences librarian at [the University of Toronto] and articles were identified through searches in EMBASE (44), CINAHL (1), JSTOR (63), and SCOPUS (37). EMBASE was selected rather than Medline or PubMed based on consultation with a health sciences librarian as it captures more international health journals. Moreover, a preliminary search in Medline yielded only one relevant article, which was also duplicated in the EMBASE search. Searches were limited to studies published in English or Spanish between January 2020 and June 2021. This timeframe was selected to coincide with the development of COVID-19 vaccines. The literature was considered in relation to two concepts: “COVID-19 Vaccination” and “Venezuelans”. Following is an example of the search terms used in SCOPUS database searches ((COVID-19) OR (Sars-CoV-2) OR (coronavirus)) AND ((vaccin*) OR (immuniz*)) AND (Venezuela*). Articles underwent two stages of screening. The peer-reviewed literature search yielded 142 results after removing three duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and 12 articles underwent full-text review, five of which were included. Review of reference lists and searches in Google Scholar yielded eight additional manuscripts for a total of 13 article s. Based on the full-text review, one peer-reviewed article was excluded because it did not address issues of access to COVID-19 vaccines, while five were excluded because they did not discuss issues of access for Venezuelan migrants.

Country-level government policies: Team members identified the official Ministry of Health website and reviewed links, documents, and news related to COVID-19 vaccination plans for the six countries hosting the majority of Venezuelans in the Latin American region. If migrants' access to vaccines was not explicitly mentioned, additional searches were conducted in Google, Qwant, and government websites. The researchers searched various online journalism sources containing government statements related to COVID-19 vaccination. Searches were conducted in Spanish and Portuguese by two native Spanish-speakers, one of whom is fluent in reading Portuguese. COVID-19 vaccination policies were evaluated in brief for 18 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, while an in-depth review of the available documents and government websites was conducted for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Gray literature: Searches were conducted in English for publications and reports by Non-Governmental Organizations, multilateral agencies, conference proceedings, and news media. Searches were conducted on the websites of the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), International Organization for Migration (IOM), Response for Venezuelans (R4V), World Bank, Mixed Migration Center (MMC), Migration Policy Institute, Migration Data Center, ACAPS, the Gavi Institute, and ReliefWeb. English-language publications were selected for close review based on relevancy of information pertaining to vaccine access for migrants with particular attention paid to Venezuelan migrants in the Latin American region. Initial searches resulted in 74 publications to be screened. Publications were excluded based on not addressing COVID-19 vaccine access or Venezuelan migration; 37 publications underwent full-text review and 13 were included in our analysis. References and cited materials within the 37 documents were further assessed resulting in an additional three sources included in analysis.

3. Theoretical frame

Research questions, data extraction and analysis were guided by a Latin American Social Medicine (LASM) approach which understands social and economic conditions as profoundly impacting health, disease, and the practice of medicine (Waitzkin et al., 2021). Our methodological approach to the scoping review and subsequent analysis thus situates national COVID-19 vaccination policies within broader understandings of health and disease as affected by social and political conditions (Birn and Muntaner, 2019), and shaped by capitalism and neoliberalism (Vasquez et al., 2019). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, country-level policies may impact health and disease for Venezuelan migrants by restricting access to safe and effective vaccines. However, it is also prudent to explore COVID-19 vaccination policies in Latin America and the Caribbean in the context of neoliberal policies which have left public health systems underfunded and overburdened. Indeed, neoliberal austerity measures promoted by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund resulted in cuts to social services and public health care across Latin America and the Caribbean (Crisp and Kelly, 1999), leaving public health systems across the region particularly ill-equipped to respond to COVID-19. Guided by LASM, we join with scholars and advocates calling for a rights-based, social justice-oriented approach to COVID-19 vaccination and underscore the sociopolitical factors that make vaccine access for Venezuelan migrants especially significant.

4. Results

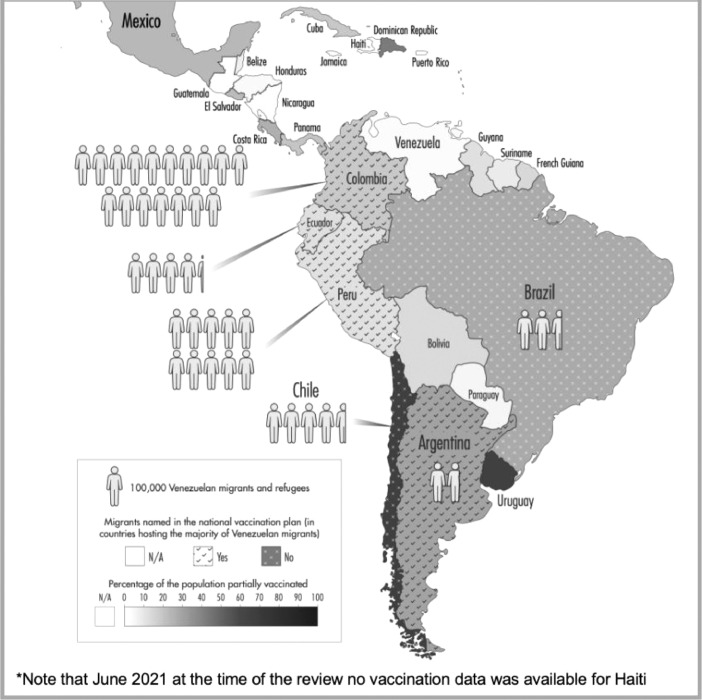

Results from the country-level policies revealed a heterogeneous and shifting policy landscape amid the COVID-19 pandemic which strongly juxtaposed calls to action evidenced in the peer-reviewed and gray literature. Results below are organized by the summative content analysis which found three major domains in the existing literature related to COVID-19 vaccine access for Venezuelan migrants in Latin America: (1) Migrant, Refugee, who? Terminology and implications for vaccine access; (2) Discriminatory and/or ambiguous public policies limit access for Venezuelan migrants; and (3) Pervasive stigma limits equitable vaccine access. Refer to Fig. 1 for estimated number of Venezuelan migrants, percentage of population covered by at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and country-level legislation surrounding vaccine access for migrants. A detailed analysis of migration policies and access to COVID-19 vaccination by six primary host countries is presented in Table 1, and a summary of national vaccination policies’ inclusion of migrants is presented in Table 2. Policies specific to Venezuelan migrants noted in tables.

Fig. 1.

Citations: (XXX, 2021b; Equilibrium CenDE, 2021b, 2021c).

Table 1.

Summary of policies impacting migrants access to COVID-19 vaccines until June 2021.

| Legal Processes to regularize Migration | Access to COVID-19 Vaccination | Other country-specific dynamics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina (Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, 2020; Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, 2021; Ministerio de Salud 2020; Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, 2004) | Disposition 1904/2020 "Certificado Electrónico de Residencia Precaria" (Electronic Certificate of Precarious Residence). Online system that allows migrants from Mercosur countries with irregular status to apply for a precarious residency certificate. Disposition 673/2021: Extends temporary, transitory, or precarious residency that expired after mid-March 2020. | The vaccination plan applies independent of migratory status, meaning it is available to migrants with regular or irregular status. According to the "Plan Estratégico de Vacunación contra Covid-19 (Resolución 2883/2020)" (Strategic Plan for Covid-19 Vaccination), once high-priority groups are vaccinated (health care workers, armed forces, teachers, older adults, and adults with chronic conditions), prioritization of vaccines will be based on social vulnerability criterion, including migration status. | Migratory Law No. 25.871 (Article 8): Health care and/or social assistance cannot be denied based on migration status. |

| Brazil (Peduzzi, 2021; Presidência da República Secretaria-Geral, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, and Presidência da República 2021; Ministério da Saúde, 2021; Secretaria Extraordinária de Enfrentamento à COVID-19 May, 2021) | "Operação Acolhida" (Operation Welcome): A humanitarian response to mass migration from Venezuela. With support from UN agencies and civil society organizations, provides services such as shelters, support with registration and documentation for migrants and refugees in the northern states of Roraima and Amazonas. Law No. 13.445: Waives fees for humanitarian visas and recognizes identity documents (residency permits and asylum applications) that expired after March 2020. | Vaccination plan includes all people in Brazil, but migrants are not mentioned in the priority list, and the vaccination guidelines do not instruct migrants with irregular status on how to access vaccines. While “Sistema Único de Saúde” (SUS) (Unified Health System) provides health coverage (including access to COVID-19 vaccination) regardless of migratory status, the government recommends proof of "Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas" (CPF) (Naturalized Persons Registry) or "Cartão Nacional de Saüde" (CNS) (National Health Card) to access COVID-19 vaccines. | Law N° 13.445: Grants access to health and social services regardless of nationality or migration status. Migrants can apply for a “Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas” (CPF) (Naturalized Persons Registry) for free, which grants access to health care (including vaccination) through “Sistema Único de Saúde” (SUS) (Unified Health System). |

| Chile (Vargas, 2021; Andina, 2021; Departamento Inmunizaciones DIPRECE, 2021; Ministerio de Salud, 2021; Ministerio de Salud, 2021; Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2021) | Law No. 21.325: Migrants with irregular status who arrived prior to March 18, 2021, can apply for a temporary visa. Those who entered “illegally” can self-report to police and receive "Fonasa A" status, granting access to health care, including COVID-19 vaccination. | Ministry of Health vaccination policy grants access to COVID-19 vaccination regardless of migratory status; requires ID documents (e.g., passport, FONASA card, ID from country-of-origin, etc.). However, the vaccination plan explicitly excludes people with a transitory visa. Vaccination guidelines contain no information about inclusion of migrants in vaccination plan. | Law No. 21.235 also facilitates deportation of migrants with irregular status. Contradictions between Ministry of Health and Ministry of Foreign Affairs policies and rhetoric have produced confusion surrounding vaccine eligibility for migrants with irregular status. |

| Colombia (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores 2021; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2021) | Decree No. 216–2021: Facilitates regularization of migrants with irregular status who arrived prior to January 31, 2021. Requires multiple valid or expired ID. | Vaccination plan grants resident migrants access to vaccines through the Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud (Ministry of Health and Social Protection) or by registering with 'Migration Colombia'. Migrants with irregular status must be approved for the Estatuto Temporal de Protección para Migrantes. (Temporary Protection Status for Migrants) | Government has defended its decision to exclude migrants with irregular status from vaccination, stating this would lead to a 'stampede' of migrants. |

| Ecuador (Guerra, 2021; Ecuador, 2020; Jumbo, 2021; El Universo, 2020) | Decree No. 826 (July 25, 2019, to August 13, 2020): Expedites online visa applications, including the VERHU humanitarian visa. Migrants must provide documentation to apply and pay 50 USD. On June 17, 2021, President Guillermo Lasso announced a new regularization plan for Venezuelan migrants, but details are not yet available as of June 18, 2021. | Ministry of Health COVID-19 vaccination is updated regularly, including details of the groups eligible for vaccination. Migrants are included in the third of four phases of the national vaccination plan "9/100″. The third phase is expected to occur from July 15th to August 30th, 2021. Migrants who have not legalized their migratory status can register with the help of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ecuador to get vaccinated. | June 14, 2021: Vice-Minister of Governance and Health Surveillance stated that vaccination clinics were instructed to ensure Venezuelan migrants with chronic conditions or living in vulnerable situations are included in the "9/100″ vaccine strategy. |

| Peru (Presidencia de la República, 2020; Ministerio de Salud, 2021; Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones, 2021) | Decreto Supremo 010–2020-IN: Expedites regularization of migrants with irregular status who arrived prior to October 20, 2020. Requires a current passport or other international travel documents. | Health policy N°133 includes non-Peruvians in vaccination plan, which includes resident migrants but does not mention migrants with irregular status. Migrants with irregular status are instructed to update their information online through the Padrón Nacional de Vacunación Universal (National Register for Universal Vaccination) | Migrants are mentioned in health policies and vaccination plans but migrants with irregular status are not. Health care providers can determine whether to vaccinate migrants with irregular status. |

Note: Gray shading indicates specific examples for Venezuelan migrants. .

Table 2.

COVID-19 vaccination policies until June 2021 by top six countries hosting the majority of Venezuelan migrants.

| Argentina | Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Ecuador | Peru | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migrants named in the vaccination plan |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Migrants with an irregular migration status named |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Venezuelan migrants named |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Specific documentation needed for vaccination |  |

|

|

|

|

|

4.1. Migrant, refugee, who? Terminology and implications for vaccine access

Across the academic and gray literature, and country-level policies, there is a high degree of variability in the terms used to define migrants, and authors largely do not define the terms used or differentiate between migrants with or without legal status (Bojorquez et al., 2021; Orcutt et al., 2020; Cabieses et al., 2020). In the literature assessed, there is no universal definition for the term “migrant”’. For example, in Peru the national vaccination plan uses the term "extranjeros residentes” (foreign residents) and refugees, while in Colombia terminology adopted includes migrants in regular and irregular condition, and in Argentina government documents only use the term migrant. Yet, most gray literature reviewed cited the IOM definition: “a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons” (International Organization for Migration, 2015).

Conversely, the term “refugee” refers to a person in an extremely vulnerable situation with urgent protection needs (International Organization for Migration, 2015). According to international treaties, once a person is recognized as a ‘refugee’, they qualify for various public goods, such as health care (Riggirozzi et al., 2020). While variations of the term ‘migrants’ were found in most of the literature reviewed, scholars have previously advocated for all Venezuelans to be termed ‘refugees’ given the magnitude of Venezuelan displacement which has surpassed the Syrian crisis of 2015 (Freier and Parent, 2019).

Noting the complexity within the term ‘migrant’, Chile has modified the term to “extranjeros en situación irregular” (Mennickent, 2021) (foreigners in an irregular situation) emphasizing migrants as ‘foreigners’ and differentiating between those with formal “estatus migratorio” (migratory status) and those who are not residents or visa applicants, “todos los otros extranjeros” (all the other foreigners) (Vargas, 2021). Although the Chilean Constitution recognizes the right to health for migrants (Cabieses et al., 2020), the Minister of Foreign Affairs has publicly stated that “extranjeros en situación irregular” (foreigners in an irregular situation) will not be vaccinated against COVD-19 (Mennickent, 2021). Nevertheless, the latest Ministry of Health policy (Vargas, 2021; Andina, 2021) underscores that anyone with identification, such as a passport, identification from country of origin, and/or documentation demonstrating they have self-reported to the police as having entered the country without official documentation, can receive a vaccine.

In Ecuador terms used include “población en situación de movilidad” (mobile populations) or “migrantes que no han legalizado su situación migratoria” (migrants who have not legalized their migratory status) (Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021a). Migrants or “población en situación de movilidad” are included in the vaccination plan's third phase expected to proceed in mid-July 2021. The vaccination plan “9/100″, which seeks to vaccinate nine million people in 100 days, mentions that “migrantes que no han legalizado su situación migratoria” (migrants who have not legalized their migratory status) can access further support from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ecuador (Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021a, 2021b).

The inconsistent use of terminology results in confusion surrounding if migrants, and which type of migrants, can access vaccines. Irregular migrants, often not differentiated from regular migrants, are further marginalized by their lack of documentation. Their irregular migratory status in tandem with physical precarity increases their vulnerability to disease and makes accessing healthcare significantly more difficult. In Brazil poor living conditions, difficulty accessing the health service, the language barrier, and the lack of employment are some of the many factors that place refugees and other migrants in COVID-19 risk groups (Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021c). With a lack of documents and a closure of public offices, people with irregular migration status are unable to obtain emergency aid the federal government created during the pandemic (Standley et al., 2020). Brazil's vaccination plan emphasizes “refugiados residentes em abrigos” (refugees in shelters) as a population with increased social and economic vulnerability to COVID-19; nonetheless, migrants are not explicitly included as a priority group within Brazil's national vaccination plans (Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021d). This is further reflected in gray and peer-reviewed literature which frequently highlight migrants’ unique vulnerability to disease and call for their inclusion in national vaccination plans (Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021e).

Our review of country-level policies found unclear and, at times, conflicting information regarding vaccine eligibility, which was further exacerbated by inconsistent use of terminology to refer to migrants. These inconsistencies and ambiguities in the use of terminology can make it more difficult to ascertain who is eligible for vaccines, when and where they can go to access vaccines. Results underscored that country-level policies differentiated, at times arbitrarily, between refugees, irregular migrants, and regular migrants, with important implications for vaccine access. While the international right-to-health legislation prohibits discrimination based on migration status (UN General Assembly, 2008) and urges states to refrain from denying access to preventive health services to non-citizens (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1976), these results suggest the need for further guidance on terminology to better contend with migrants’ social vulnerabilities. This is particularly relevant for Venezuelan migrants who belong to the larger ‘forcibly displaced’ persons category which can include the range of experiences and vulnerabilities associated with being a refugee, internally displaced, or asylum seeker (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Right, 2021).

4.2. Discriminatory and/or ambiguous policies limit access for Venezuelan migrants

Across the literature reviewed, the challenges regarding Venezuelan mass migration and changing scope of best practices for COVID-19 were noted. Indeed, scholars have referred to Latin America's inconsistent vaccine rollout as a “gamble” to think that recovery from COVID-19 is possible while millions of Venezuelans within host countries are unable to access vaccines (Villareal and Mazza, 2021). Status of migration emerged as a contested domain, heightening the inequities in accessing vaccines. While there are numerous ‘urgent’ calls in the peer-reviewed literature for governments to “adopt policies that safeguard the right to health of migrants and refugees regardless of their legal status” (Riggirozzi et al., 2020), this was far from the reality within existing policies. Results from the gray literature revealed that certain countries grant access to vaccines based on legal status within the country, including in Colombia which plans to exclude migrants who are ineligible for the Temporary Protection Status from its vaccination plan (Rahhal, 2021). For example, migrants with irregular status, referring to omission of formalized entry process and/or recognized legal status within host countries, were explicitly excluded from Costa Rica's vaccination plan. Rather, Costa Rica is only vaccinating ‘regular’ migrants and those officially classified as refugees by the UNHCR, an explicit example of how politics and connotations of “refugee” versus “migrant” are tangibly impacting policy and healthcare (Zúñiga, 2021).

Given the heighted experience of xenophobia and discrimination targeting Venezuelan migrants, it is critical to draw attention to the ways in which policies also perpetuate discrimination. For instance, while Chile has implemented a process for irregular migrants to access vaccines, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has stated publicly that irregular migrants will not be vaccinated in Chile (Mennickent, 2021). The literature also evidenced numerous examples of policies that did not overtly exclude Venezuelan migrants, but were vague and lacked coherence, raising questions as to whether Venezuelans could access vaccines in practice. For example, under the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) all people in Brazil are provided access to COVID-19 vaccines regardless of migratory status. Nevertheless, proof of certain documents such as the Naturalized Persons Registry and/or a National Health Card is still needed, posing as a potentially critical barrier for migrants.

While the pandemic is rapidly evolving and thus policies are being modified, failure to clarify how migrants are included in national vaccination plans introduces barriers in accessing prevention and care and can lead to discrimination, especially of those most vulnerable. For example, Peru, Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador have policies which in theory afford some degree of access to vaccination for migrants, while only two (Colombia and Ecuador) include Venezuelans explicitly (XXXX, 2021c; Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021a). Similarly, although Trinidad and Tobago's national vaccination plan includes Venezuelan migrants, there is no mention of whether irregular migrants are included and/or what associated processes might entail (XX, 2021a). These contradictory policy stances and outright exclusion from vaccination efforts limit the number of Venezuelans accessing vaccines in Latin America.

In our in-depth review of government policies, only Colombia and Ecuador mention Venezuelan migrants in their COVID-19 vaccination policies, and both have separate processes for irregular migrants to access the vaccines. Yet, naming Venezuelan migrants does not necessarily lead to vaccine access, which can still be restricted by various factors. In Colombia, all migrants with regular status can access COVID-19 vaccines by showing a residence permit known as the “PermisoEspecial de Permanencia” (PEP) (Special Permanency Permit), or other documents proving their migratory status. Irregular migrants, however, must apply for Temporary Protection Status (TPS) to access vaccines (Zard et al., 2021). However, the gray literature indicates that TPS is only available to migrants who arrived prior to January 31st, 2021, and at the time of writing this article, no applications for TPS had been approved (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2021). Further, those with a criminal record are ineligible for TPS, and ultimately Colombian immigration services could reject an applicant even if they meet all criteria (XX, 2021a). The differential access to vaccination based on migratory status inherent within Colombia's vaccination policy threatens access to COVID-19 vaccines for the more than half of Venezuelans without formal migration status in Colombia.

Although migrants and/or Venezuelan migrants were named in some policies, bureaucratic minutiae made it difficult to determine in practice whether Venezuelans can access COVID-19 vaccines. For instance, Colombia, Chile, and Brazil required migrants to submit formal documents, such as passports, proof of status in-country, or enrollment to healthcare system, to access vaccines. Similar processes were found in Guatemala, Dominica, and Barbados, where an identification number is required for vaccination (Garza, 2021). Delays in processing these documents and closures of government offices due to the pandemic can prevent migrants from accessing the required documentation and consequently from accessing vaccines (Standley et al., 2020). Although less direct than countries like Costa Rica where irregular migrants are excluded from vaccination, the vagueness and ambiguities evidenced in the country-level policies flag important embedded barriers to an equitable and rights-based approach to health not only during a global pandemic but also for communities undergoing mass displacement.

These complex, incoherent bureaucratic policies present structural barriers in accessing safe and effective vaccines for all migrants in Latin America. According to IOM research, although migrants with regular migratory or refugee status are included in the majority of National Vaccination Plans, there is greater uncertainty as to whether they are included in practice. In many countries, it is unclear if migrants with irregular migratory status are included, both in National Vaccination Plans and in practice (Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones, 2021). Although 110 countries globally have named refugees in their vaccine distribution plans, pervasive discrimination and fears related to disclosure of migration status can deter migrants from seeking vaccines even if they are eligible (Zard et al., 2021).

These ambiguities in access to health care extend beyond vaccine access and have also been reported regarding eligibility for COVID-19 treatment. Given the magnitude of Venezuelan migration in the Latin American region, existing evidence suggest that the lack of clarity regarding eligibility has fueled confusion among Venezuelan migrants as to if and how they could access needed COVID-19 related services. According to the Mixed Migration Center, 39% of Venezuelans in Colombia and 75% in Peru answered that they believed they could not access healthcare to seek treatment for COVID-19. Additional barriers for Venezuelan migrants seeking health care services identified in the literature included: informal labor and precarious employment, food insecurity, lack of knowledge of available services (Cubillos-Novella et al., 2020), issues of cost, as well as distrust of authorities and fear related to disclosure of migration status (Zard et al., Apr. 2021).

4.3. Pervasive stigma limits equitable vaccine access

Specific to Venezuelan migrants, our review identified pervasive stigmatization and discrimination within documents related to COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, policies, and access more generally. First, in the context of limited resources, Venezuelan migrants in Latin America are often socially constructed as ‘outsiders’ to justify exclusion from vaccination campaigns (Riggirozzi et al., 2020). In Chile, refugees and migrants have been blamed for the spread of COVID-19, and these stigmatizing social norms have resulted in increased violence against Venezuelans (Zard et al., 2021). In late 2020, President Duque of Colombia stated that displaced Venezuelans residing in his country would be excluded from COVID-19 vaccination for fear that it would lead to a stampede of migrants (Daniels, 2020). These examples reflect the ways that stigma toward Venezuelan displaced persons is reproduced through blaming the ‘foreign other’ for epidemic spread—a common and recurrent historical trend in COVID-19 and other pandemics (Logie, 2020). This framing of displaced persons as vectors of COVID-19 in community and political discourse both elevates risks of violence and COVID-19 vaccine exclusions.

Second, legally enforced movement restrictions in COVID-19 to halt pandemic spread may facilitate stigma and xenophobia through authoritarian means (Logie and Turan, 2020; Perez-Brumer and Silva-Santisteban, 2020). This scoping review documented the use of military tactics to stop and contain the mobility of Venezuelan migrants, particularly along the borders of Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, and Peru (XX, 2021a). Notably, due to hardships exacerbated by COVID-19, flows of Venezuelan migrants have become bidirectional, not only into host countries but also with Venezuelans seeking to return to Venezuela (i.e., reverse migration). An estimated 130,000 Venezuelans have reportedly returned to Venezuela “from or through Colombia since the border closure” on March 14, 2020 (Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones, 2021). While WHO, PAHO, and UNICEF have collaborated to implement temporary shelters to assist these migrants with food and healthcare needs, many shelters in remote and border areas have experienced disrupted service or have been closed altogether due to COVID-19 (World Health Organization 2020). While reports on accessibility of vaccines in these remote border regions is limited, there is documentation noting that even if migrants were able to return to Venezuela, they could be labeled as COVID-19 “biological weapons” and stigmatized as carriers of COVID-19 (Standley et al., 2020).

Third, stigma toward Venezuelan migrants is reported in healthcare settings through nationalist rhetoric and xenophobia and has implications for reducing vaccine access and uptake. For instance, in Brazil, media has documented complaints of xenophobic treatment of Venezuelan migrants seeking health care (Vargas, 2021). This discrimination has been recorded despite guaranteed access to the Unified Health System (SUS) for migrants under the Brazilian Constitution, and more recently, the new Immigration Law (No. 13,445/2017). However, in practice, migrants seeking services through SUS reported difficulties due to the language barrier, lack of guidance, and incidents of explicit prejudice (Branco, 2020). In Peru, xenophobic discourse targeted at Venezuelan migrants has been a core campaign platform throughout the 2021 presidential elections, and has led to concerns among Venezuelan migrants as to whether they will be able to access essential medicines and other social services (Equilibrium CenDE, 2021a). Together, this review underscores the importance of addressing the social and political discourse on migrants as vectors of COVID-19, and reducing xenophobia, to increase vaccine access specifically (and healthcare access more generally) among Venezuelan migrants. Due to the ambiguous and at times arbitrary use of terminology in national COVID-19 vaccination plans, combined with the increased stigma, xenophobia, and violence enacted against Venezuelan migrants, this group can fall through the cracks when not explicitly mentioned in vaccination plans.

5. Discussion

Findings presented underscore the extreme complexity and associated variability of providing access to COVID-19 vaccines for Venezuelan migrants across Latin America. While there are more than 5.6 million Venezuelan migrants globally, over 4.9 million Venezuelans migrants remain in Latin America (XXX, 2021b, XXXX, 2021c; UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2021). Paralleling the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination levels vary greatly by country, with Chile leading with a reported 62% of the population having received at least one dose compared to countries such as Peru with 8% or Paraguay with just 3% (Equilibrium CenDE, 2021b). The review identified key factors limiting COVID-19 vaccine access for Venezuelan migrants: tensions around terminologies used for displaced communities; variable and contradictory vaccine policies both nationally and regionally; and pervasive stigmatization of migrants impacting policy creation and individual-level access and uptake even if eligible.

In tandem with the ambiguity within policies that impede migrants’ access to vaccines, the theoretical framework as applied to COVID-19 vaccination in this review also highlights how other sociopolitical forces (such as pervasive stigma) influences the logics of when Venezuelan migrants are counted as vulnerable and/or target populations for vaccines. As a result of social exclusion and economic precarity, Venezuelan migrants face a unique set of risks within host countries that increase their vulnerability to COVID-19 (Standley et al., 2020; Monshipouri et al., 2020). Factors documented in peer-reviewed and gray literature include crowded living arrangements, poor access to water and sanitation hygiene, and limited access to personal protection equipment. A Latin American Social Medicine approach allows us to better understand the sociopolitical drivers of these barriers within the context of limited vaccine supply and years of austerity measures leaving public healthcare systems across Latin America underfunded and overburdened even before COVID-19. Indeed, as of June 2021, most Latin America and the Caribbean countries have fully vaccinated less than 15% of residents, compared to over 45% fully vaccinated in the United States (Equilibrium CenDE, 2021b).

The response to COVID-19, especially access to vaccines, has shown the limits of multilateral responses to support Latin American countries to address the public health crisis in an equitable, rights-based way. COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) is a global initiative charged with ensuring “quick, fair, safe, and global equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines” (Acharya et al., 2021). Yet, as of March 30th, 2021, over 85% of vaccine doses were delivered to high- and upper-middle income countries, while only 0.1% were delivered to low-income countries (Zard et al., 2021). This is unsurprising as industrialized countries participating in COVAX during vaccine development had already secured millions of doses surpassing the quantity needed for their populations. Thus, COVAX failed to distribute vaccines to Latin America and the Caribbean, resulting in widespread vaccine shortages in the region. Integral to the success of global efforts to eradicate polio have been intensive vaccination in conflict-affected areas, and prioritization of mobile and marginalized populations (Zard et al., 2021). Yet, results showed that current COVID-19 vaccination trends fall short of the peer-review and gray literature recommendations for equity and rights-based approaches to vaccination that prioritize migrants. The slow rollout of vaccines is compounding the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America, which is now widely considered to be suffering the “deepest and most severe health and economic…impact of any developing region” (Villareal and Mazza, 2021).

Like the COVID-19 pandemic, mass migration from Venezuela is a dynamic phenomenon. Policy responses to both phenomena likewise are rapidly shifting. The findings reported here thus should be interpreted with care. Nonetheless, these findings provide an important comparative baseline by which the policy-context currently shaping migrant health in these settings can be further assessed. Further research can illuminate the differential health impact of the policies discussed here, as well as the broader socioeconomic variables impacting Venezuelan migrants’ access to COVID-19 vaccines. Further research is also needed to understand fully the impact of policies that acknowledge migrants with ambiguity or not at all, as these may indicate either neutrality toward migration status or their exclusion—detailed attention is necessary regarding the specific dynamics of on-the-ground policy implementation. Indeed, with an eye to the complexity of policy implementation, this review demonstrates the utility of concurrently examining three types of literature (peer-reviewed, gray literature, and governmental policy) to assess the range of directives potentially shaping migrant health in pandemic times.

By querying the timely question of how Venezuelan migrants access vaccinations we seek to not only understand the present moment but also better understand how to prepare and respond to future pandemics and influxes of displaced peoples. These are intersectional and evolving crises and attention must also be drawn to the magnitude of Venezuelan mass migration and the devastating impact of COVID-19 in the region. We join scholars and multilateral agencies advocating strongly for the inclusion of migrants, regardless of their migratory status, and refugees in national vaccination strategies (Orcutt et al., 2020; Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2021e; Zard et al., 2021). Importantly, while gaps can still exist between naming and including migrants in vaccination plans, it is a critical first step to securing needed resources and advancing a rights-based response to COVID-19 in the region.

6. Conclusion

While healthcare access is critical for all migrants, given the magnitude of the Venezuelan displacement as the second largest international displacement globally in contemporary history, its unprecedented burden on Latin American countries, and the reactionary violence and xenophobia it has engendered, the question of vaccine access for this group is especially significant. The Venezuelan migrant crisis and the vaccination of migrants should and can be addressed regionally in Latin America. Further, a rights-based regional response necessitates not only global policies that ensure the equitable distribution of vaccines but also accountability of the international treaties and commitments that countries have signed to drive national health policies amid times of crisis. Understandably, however, given uncertainty surrounding the vaccine supply and recent extreme political views on migration, the current state of public policies in Latin America remains messy and ever evolving. Full integration of migrants and refugees into public health strategies is not only a matter of social justice and a rights-based approach to health, but also a pragmatic public health strategy necessary to stop the COVID-19 pandemic globally.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), Insight Development Award.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100072.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Acharya K.P., Ghimire T.R., Subramanya S.H. “Access to and equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccine in low-income countries,”. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):54. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00323-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andina, A.P.N., “COVID-19: Chile da marcha atrás y aclara que vacunación incluye a extranjeros irregulares,” Nov. 02, 2021. https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-covid19-chile-da-marcha-atras-y-aclara-vacunacion-incluye-a-extranjeros-irregulares-833441.aspx (accessed Jun. 02, 2021).

- Birn A.-.E., Muntaner C. “Latin American social medicine across borders: south-South cooperation and the making of health solidarity,”. Glob. Public Health. 2019;14(6–7):817–834. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1439517. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojorquez I., et al. “Migration and health in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond,”. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1243–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00629-2. Apr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco, M., “Refugiados e imigrantes denunciam xenofobia no sistema público de saúde durante pandemia,” Metrópoles, Oct. 18, 2020. https://www.metropoles.com/brasil/refugiados-e-imigrantes-denunciam-xenofobia-no-sistema-de-saude-durante-pandemia (accessed Jun. 07, 2021).

- Cabieses B., Rada I., Vicuña J.T., Araos R. “Reporte situacional: el caso de migrantes internacionales en Chile durante la pandemia de COVID-19,”. Lancet Migr. 2020 Dec. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-González D., Echeverría-Estrada C. “Venezuelan migrants and refugees in Latin America and the Caribbean: a regional profile,”. Migr. Policy Inst. 2020:31. Aug. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp B.F., Kelly M.J. “The socioeconomic impacts of structural adjustment,”. Int. Stud. Q. 1999;43(3):533–552. [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos-Novella A., Bojorquez-Chapela I., Fernández-Niño J.A. “Situational brief: report on Venezuelan migrants in Colombia and the COVID-19 pandemic,”. Lancet Migr. 2020 May https://www.migrationandhealth.org/migration-covid19-briefs. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, J.P., “Alarm at Colombia plan to exclude migrants from coronavirus vaccine,” the Guardian, Dec. 22, 2020. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/dec/22/colombia-coronavirus-vaccine-migrants-venezuela-ivan-duque (accessed Jun. 28, 2021).

- Departamento Inmunizaciones DIPRECE, “GRUPOS objetivos para vacunación contra SARS-COV-2* Según EL Suministro DE Vacunas.” Mar. 03, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GRUPOS-OBJETIVOS-3-marzo-2021.pdf

- Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, “Ley de Migraciones N°2587.” Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina., de enero del 2004. [Online]. Available: http://www.migraciones.gov.ar/pdf_varios/campana_grafica/pdf/Libro_Ley_25.871.pdf

- Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, “Disposición 1904/2020.” Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina., May 16, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/disposici%C3%B3n-1904-2020-336399/texto.

- Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, “Disposición 673/2021.” Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina., Mar. 22, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/disposici%C3%B3n-673-2021-348190/texto

- Cancillería del Ecuador, “La regularización de venezolanos fue un proceso inédito para el Ecuador – Cancillería,” Aug. 31, 2020. https://www.cancilleria.gob.ec/2020/09/01/la-regularizacion-de-venezolanos-fue-un-proceso-inedito-y-exitoso-para-el-ecuador/ (accessed Jun. 17, 2021).

- El Universo, “37.619 venezolanos recibieron la visa humanitaria en casi un año,” El Universo, Aug. 13, 2020. https://www.eluniverso.com/noticias/2020/08/13/nota/7940437/venezolanos-visa-humanitaria-verhu-ecuador (accessed Jun. 18, 2021).

- Equilibrium CenDE, “Segunda encuesta regional: migrantes y refugiados Venezolanos,” Equilibrium CenDE, 2020. https://equilibriumcende.com/segunda-encuesta-regional-2020/ (accessed Jun. 24, 2021).

- “Access to health services for Venezuelans in Colombia and Peru during the COVID-19 pandemic,” mixed migration centre, Mar. 2021. https://mixedmigration.org/resource/4mi-snapshot-access-to-health-services-for-venezuelans-in-colombia-and-peru-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed May 28, 2021).

- “Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations - statistics and research,” Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed Jun. 03, 2021).

- “Latest updates: COVID-19 vaccination charts, maps and eligibility by country,” Reuters. Accessed: Sep. 29, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/vaccination-rollout-and-access/

- Freier L.F., Parent N. The regional response to the Venezuelan exodus. Curr. Hist. 2019;118(805):56–61. doi: 10.1525/curh.2019.118.805.56. Feb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garza, I., “Achieving COVID-19 vaccination for all migrants in Latin America – MMB Latin America.” https://mmblatinamerica.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2021/03/25/achieving-covid-19-vaccination-for-all-migrants-in-latin-america/ (accessed Jun. 28, 2021).

- Guerra, J., “Ecuador anuncia nueva regularización de venezolanos,” Jun. 17, 2021. https://www.lahora.com.ec/ecuador-nueva-regularizacion-venezolanos/ (accessed Jun. 18, 2021).

- Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. “Three approaches to qualitative content analysis,”. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration, “Key migration terms,” International organization for migration, Jan. 14, 2015. https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms (accessed Jun. 25, 2021).

- Jumbo, B., “Acnur y el gobierno de Ecuador definen el mecanismo para vacunar a los extranjeros en condición de movilidad como venezolanos y colombianos,” El Comercio, Jun. 14, 2021. https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/ecuador/vacunacion-extranjeros-venezolanos-covid-ecuador.html (accessed Jun. 17, 2021).

- Logie C.H., Turan J.M. “How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2003–2006. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02856-8. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie C.H. “Lessons learned from HIV can inform our approach to COVID-19 stigma,”. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020;23(5):e25504. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, G. and Schipani, A., “Venezuela's imploding economy sparks refugee crisis,” Financial Times, Apr. 16, 2018. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ft.com/content/a62038a4-3bdc-11e8-b9f9-de94fa33a81e

- Mennickent, C., “Gobierno categórico: no podrán vacunarse extranjeros turistas o irregulares,” BioBioChile - La Red de Prensa Más Grande deChile, Feb. 10, 2021. https://www.biobiochile.cl/noticias/nacional/chile/2021/02/10/gobierno-categorico-no-podran-vacunarse-extranjeros-turistas-o-irregulares.shtml (accessed May 31, 2021).

- Ministério da Saúde, “Perguntas e Respostas,” Jul. 06, 2021. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/coronavirus/perguntas-e-respostas.

- Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, “Decreto 216 Por medio del cual se adopta el Estatuto Temporal de Protección para Migrantes Venezolanos.” Bogotá D.C., Colombia. [Online]. Available: https://www.migracioncolombia.gov.co/normas/por-medio-del-cual-se-adopta-el-estatuto-temporal-de-proteccion-para-migrantes-venezolanos-decreto-216-del-1-de-marzo-de-2021 2021

- Ministerio de Salud Pública, “Plan de vacunacion 9 100, Respuestas a inquietudes ciudadanas sobre el plan de vacunacion 9/100,” May 31, 2021. https://www.salud.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/31-05-2021_-Preguntas-y-Respuestas_Plan-de-Vacunacion-9100_validado.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud Pública, “Cronograma semanal de vacunación. Fase 1: salvamos vidas 1era dosis,” n.a. https://lugarvacunacion.cne.gob.ec/boletin/cronograma_semanal.pdf 2021

- “Integration of Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants in Brazil - Brazil,” ReliefWeb, May 19, 2021. https://reliefweb.int/report/brazil/integration-venezuelan-refugees-and-migrants-brazil (accessed May 25, 2021).

- “Interiorização beneficia mais de 50 mil refugiados e migrantes da Venezuela no Brasil,” Ministério da Cidadania. https://www.gov.br/cidadania/pt-br/noticias-e-conteudos/desenvolvimento-social/noticias-desenvolvimento-social/interiorizacao-beneficia-mais-de-50-mil-refugiados-e-migrantes-da-venezuela-no-brasil (accessed Jun. 18, 2021).

- “Migrants: guidance on equitable access to COVID-19 vaccine,” OHCHR, Mar. 08, 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26860&LangID=E (accessed May 23, 2021).

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, “Plan Nacional de Vacunación contra el COVID-19,” Bogotá, Documento Técnico 2, Feb. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://mivacuna.sispro.gov.co/MiVacuna?v1

- Ministerio de Salud, “Resolución 2883/2020.” Buenos Aires, Argentina, de diciembre del 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/disposici%C3%B3n-1904-2020-336399/texto

- Ministerio de Salud, “Aprueba lineamientos técnico operativos vacunación SARS-COV-2,” Ministerio de Salud Subsecretaría de Salud Pública, Chile, Government 1138, Dic 2020. Accessed: May 29, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RE-N%C2%BA-1138-Lineamientos-SARS-CoV-2.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud, “Complementa resolución exenta N. 1138 de 2020, del Ministerio de Salud que aprueba lineamientos técnico operativos vacunación SARS-COV-2,” Ministerio de Salud Subsecretaría de Salud Pública, Chile, Government 136, Oct. 2021. Accessed: May 29, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RES.-EXENTA-N-136_.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud, “Directiva Sanitaria N° 133-MINSA/2021/DGIESP, ‘Directiva Sanitaria actualizada para la vacunación contra la COVID-19 en la situación de emergencia sanitaria por la pandemia en el Perú.’” Lima, Perú, May 12, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1893194/Directiva%20%20Sanitaria%20N%C2%B0%20133-MINSA-2021-DGIESP%20.pdf

- Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, “LEY NÚM. 21.325, Ley de Migración y Extranjería,” Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, Chile, Government 42.934, Apr. 2021. Accessed: May 31, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://immichile.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/nueva-Ley-de-Migraciones-Ley-de-Migracion-y-Extranjeria-21325.pdf

- Monshipouri M., Ellis B.A., Yip C.R. “Managing the refugee crisis in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic,”. Insight Turk. 2020;22(4):179–200. [Google Scholar]

- O. Mur, “Venezuela situation.” UNHCR, Jun. 2018. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/64428

- Orcutt M., et al. “Global call to action for inclusion of migrants and refugees in the COVID-19 response,”. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1482–1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30971-5. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page K.R., Doocy S., Ganteaume F.R., Castro J.S., Spiegel P., Beyrer C. “Venezuela's public health crisis: a regional emergency,”. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1254–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30344-7. Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- P. Peduzzi, “Operación Acogida ya reubicó a 50.000 refugiados venezolanos,” Agência Brasil, Apr. 23, 2021. https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/es/direitos-humanos/noticia/2021-04/operacion-acogida-ya-reubico-50000-refugiados-venezolanos (accessed Jun. 07, 2021).

- Perez-Brumer A., Silva-Santisteban A. “COVID-19 policies can perpetuate violence against transgender communities: insights from Peru,”. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(9):2477–2479. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02889-z. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presidência da República Secretaria-Geral, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, and Presidência da República, “LEI No 13.445, DE 24 DE MAIO DE 2017.” https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/l13445.htm 2021.

- Presidencia de la República, “Decreto Supremo N° 010-2020-IN Que aprueba medidas especiales, excepcionales y temporales para regularizar la situación migratoria de extranjeros y extranjeras.” Lima, Perú, Oct. 21, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-supremo-que-aprueba-medidas-especiales-excepcionale-decreto-supremo-n-010-2020-in-1895950-4/

- Rahhal N. Amnesty International; 2021. “Refugees and COVID-19 Vaccinations: Part of the Solution but not Always Part of the Plan; p. 4. May. [Google Scholar]

- P. Riggirozzi, J. Grugel, and N. Cintra, “Situational brief: perspective on migrants’ right to health in Latin America during COVID-19,” Lancet Migr., Jun. 2020. Accessed: Jun. 10, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://1bec58c3-8dcb-46b0-bb2a-fd4addf0b29a.filesusr.com/ugd/188e74_543cbb0400824084abcea99479dfa124.pdf?index=true

- P. Riggirozzi, J. Grugel, and N. Cintra, “Protecting migrants or reversing migration? COVID-19 and the risks of a protracted crisis in Latin America,” p. 6, 2020.

- Secretaria Extraordinária de Enfrentamento à COVID-19, “Plano Nacional de Operacionalização da Vacinação contra Covid-19,” Ministerio de Salud, Brazil, May 2021. Accessed: May 24, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/coronavirus/publicacoes-tecnicas/guias-e-planos/plano-nacional-de-vacinacao-covid-19/view

- Standley C.J., Chu E., Kathawala E., Ventura D., Sorrell E.M. “Data and cooperation required for Venezuela's refugee crisis during COVID-19,”. Glob. Health. 2020;16(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00635-7. Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- “Migrant Inclusion in COVID-19 Vaccination Campaigns . International Organisation for Migration; 2021. https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/DMM/Migration-Health/iom-vaccine-inclusion-mapping-17-may-2021-global.pdf May Accessed: Jun. 11, 2021. [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones, “Comunicado 007 - 2021,” Plataforma Digital Única del Estado Peruano, de abril del 2021. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/migraciones/noticias/368406-comunicado-007-2021 (accessed Jun. 23, 2021).

- “Colombia Operational Update, March 2021 - Colombia,” ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/colombia/colombia-operational-update-march-2021 (accessed May 26, 2021).

- Tricco A.C., et al. “A scoping review of rapid review methods,”. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly, Committee on the elimination of racial discrimination, and general assembly, Report of the committee on the elimination of racial discrimination: seventieth session (19 February-9 March 2007). New York: United Nations, 2008.

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “International covenant on economic, social, and cultural rights, article 12(1) and 12(2),” 1976. Accessed: Sep. 16, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx

- “UNHCR global trends - forced displacement in 2020.” Accessed: Sep. 28, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globaltrends/

- F. Vargas, “Minsal recalca que solo extranjeros que realizan turismo no pueden vacunarse contra el covid-19 | Emol.com,” Emol, May 31, 2021. https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2021/05/31/1022465/Minsal-Vacunacion-Extranjeros.html (accessed Jun. 02, 2021).

- Vasquez E.E., Perez-Brumer A., Parker R.G. “Social inequities and contemporary struggles for collective health in Latin America,”. Glob. Public Health. 2019;14(6–7):777–790. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1601752. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N.F. Villareal and J. Mazza, “Latin America's vaccine gamble with Venezuelan migrants,” Apr. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/Latin.America%E2%80%99s.Vaccine.Gamble.with_.Venezuelan.Migrants.pdf

- Waitzkin H., Pérez A., Anderson M. Routledge; New York, NY: 2021. Social Medicine and the Coming Transformation. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, “COLOMBIA: through a structured and coordinated response, Colombia seeks to leave no one behind in the fight against COVID-19,” World Health Organization, 2020. Accessed: May 12, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28073

- XX, “Quarterly mixed migration update,” Mixed migration centre, Apr. 22, 2021. https://mixedmigration.org/resource/quarterly-mixed-migration-update-lac-q1-2021/ (accessed May 28, 2021).

- XXX, “Refugees and migrants from Venezuela | R4V,” Response for Venezuelans, Jun. 05, 2021. https://www.r4v.info/en/refugeeandmigrants (accessed Jun. 25, 2021).

- XXXX, “Indicatores sociales,” Instituto de investigaciones económicas y sociales. https://insoencovi.ucab.edu.ve/(accessed Jun. 24, 2021).

- A. Zúñiga, “DIMEX required for vaccination, Costa Rica says,” The Tico Times, Mar. 03, 2021. https://ticotimes.net/2021/03/03/dimex-required-for-vaccination-costa-rica-says (accessed May 31, 2021).

- Zard M., et al. “Leave no one behind: ensuring access to COVID-19 vaccines for refugee and displaced populations,”. Nat. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01328-3. Apr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.