Abstract

Purpose

Three cases of acetabular labral tear (ALT) diagnosed with sonography (US) are reported. We aim to show utility for US with the addition of manual hip traction as an adjunctive modality to the current diagnostic imaging of choice, magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA), for diagnosing ALT.

Methods

Three cases of young athletic patients with similar clinical presentations are reported. All received US examination of the hip with attention to the labrum that included a novel long-axis hip traction technique which assisted in diagnosing ALT.

Results

In the first and second cases, MRA and orthopedic consult were obtained for confirmation of the diagnosis. Arthroscopy was performed to correct the ALT. The third patient declined an MRA. Conservative management consisted of McKenzie method active care, resulting in return to sport in the third case.

Conclusion

These three cases demonstrate the clinical and sonographic presentation of ALT. The dynamic long-axis hip traction protocol facilitated the use of US as an adjunctive modality for diagnosing ALT by increasing the visualization of the defect.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40477-020-00446-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acetabular labral tear, Ultrasonography, Magnetic resonance imaging, Traction

Introduction

Acetabular labral tears (ALT) are diagnosed in 22–55% of patients presenting with hip or groin pain [1]. The prevalence is even higher in athletes who frequently utilize twisting and pivoting motions in their sport [2, 3]. However, most patients go for more than 2 years before receiving an accurate diagnosis [1]. This is problematic as ALT predisposes patients to early onset osteoarthritis. Advanced degenerative joint disease results in decreased mobility, chronic pain, and overall reduced measures of health ultimately creating a significant reduction in quality of life [3].

The labrum in the hip deepens the femoroacetabular joint and provides stability against translation of the femoral head. It also increases the surface area of the acetabulum. This distributes load and decreases stress on the articular surface of the acetabulum creating a shock absorption function. Where the femur head contacts the labrum, a seal is created. This seal maintains the synovial fluid pressure which also reduces stress on the articular surface of the joint [1, 3].

When the acetabular labrum is torn, its function is affected. A tear results in joint laxity and causes increased and abnormal motion between the femur and the acetabulum. There is an increase in load on the articular surfaces as a tear breaks the labral seal, negatively impacting the shock absorption function. The increased stress on the articular surface leads to chondral degeneration which, in turn, leads to osteoarthritis [1, 3].

Diagnosing an ALT is challenging. Both intra-articular and extra-articular pathologies have similar clinical presentations. The narrative literature review by Battaglia et al. states that in young patients who present with anterior hip pain, an ALT must be considered in addition to other differentials such as femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), iliopsoas impingement, internal snapping hip, and neuropathies that cross the anterior hip joint [2–4]. Even when taking a thorough history and performing a constellation of clinical examinations, there is a significant overlap with the clinical presentation of ALT and other pathologies of the anterior hip [3, 4]. This is due to the limited specificity of clinical examinations to accurately differentiate pain generators of the anterior hip. Clinicians are, therefore, required to utilize diagnostic imaging to confirm clinical findings, which can be cost and time inefficient [2, 4].

The current gold standard for diagnosing an ALT is arthroscopy. Prior to such an invasive procedure, patients undergo other diagnostic imaging examinations [3–5]. It is common that patients will first have a radiographic evaluation to determine if there are any structural components that are known etiologies of ALT, such as FAI, osteoarthritis, or hip dysplasia. Further diagnostic imaging is required to evaluate the labrum itself [1–3, 5].

Current options for further imaging include magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA), computed tomography arthrogram (CTA), and sonography (US). Conventional 1.5 T MRI and CT are not as reliable as their arthrogram counterparts and are generally not used [5, 6]. The gadolinium contrast addition in an arthrogram distends the joint capsule and increases the sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing intra-articular pathology [5, 6]. There is limited research on the performance of 3 T MRI in diagnosing ALT when compared to 1.5 T MRA. At this time, the conclusion is that they are equivocal studies, but this issue awaits scientific verification [7, 8].

The diagnostic imaging of choice for ALT has consistently been MRA due to the high diagnostic value reported in the literature. MRA has superior soft-tissue resolution which allows superb visualization of the labrum [3, 6]. This visualization is derived not just from the multiplanar property of MRI, but also the inclusion of contrast. However, MRA is expensive and invasive with the intra-articular injection of contrast. A few studies have been published about the utilization of CTA in diagnosing hip pathology, but the level of sensitivity reported is similar to MRA [9]. CTA has shown good spatial resolution, but utilizes ionizing radiation [9]. In early studies, the diagnostic value of US in hip pathologies was poor. More recent studies are showing increased diagnostic value when examined by an experienced sonographer. US evaluation is cost-effective, time-efficient, noninvasive, and readily offers a dynamic component to the examination [10, 11].

We report a case series that utilized US with extremity manual hip traction procedure to increase visualization of and accurately diagnose ALT. In two cases, the diagnosis from the US examination was correlated with MRA and the gold standard of arthroscopy. These three cases exemplify the utility of US with manual traction as an adjunctive imaging modality for diagnosing ALT.

Case 1

A 22-year-old white female student presented with a complaint of progressive right hip pain of one month duration. The pain was described as a deep, dull ache that localized around the right hip joint in a “C” shape from front to back and was rated at a six out of ten on the Verbal Numerical Rating Scale (VNRS) at its worst. The symptoms were provoked by sitting, standing longer than 20 min, lunging, and sleeping on her right side. Ice and aspirin provided relief for approximately 20 min. This condition began when she increased her workout routine, which consisted of high-intensity interval training, from two times per week to five times per week.

Upon physical examination, dynamic internal rotatory impingement (DIRI) and scour tests recreated the patient’s hip pain. FABER’s test on the right created pain in the ipsilateral sacroiliac joint, but not the hip. Active range of motion of the right hip was normal. Dynamic external rotatory impingement (DERI) was negative bilaterally. Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) Outcome Assessment Questionnaire calculated a 23% disability [12].

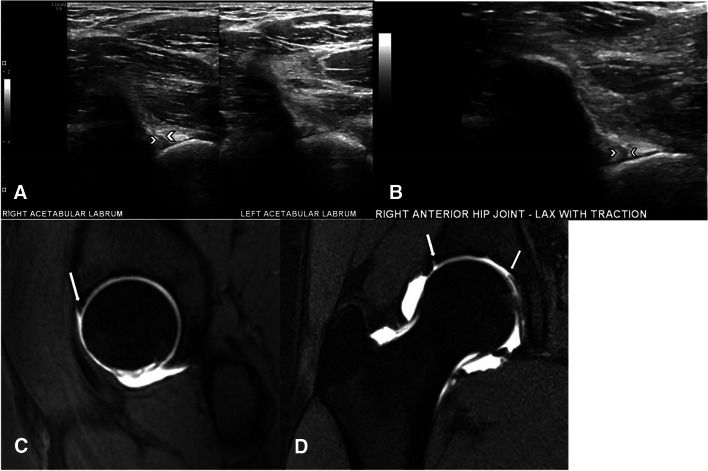

The patient was diagnosed with an anterior hip strain with possible hip impingement. Chiropractic manipulative therapy to the lumbar spine and pelvis and myofascial release were performed without improvement. Radiography was deferred and ultrasound was obtained. During US evaluation, an irregular hypoechoic line was seen to dissect through the anterosuperior portion of the right acetabular labrum that widened following manual long-axis hip traction, consistent with an ALT (Fig. 1a, b, and Online Resource 1). The femoral head and neck junction demonstrated a CAM-type FAI deformity that approximated and impacted the labrum with flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. A recommendation for MRA was made for additional evaluation of the labrum. The MRA revealed an ALT extending from approximately 11 o’clock to 3 o’clock (Fig. 1c, d). The patient was referred to an orthopedist for surgical consult.

Fig. 1.

Right ALT in a young athletic female. a US of the right hip labrum shows an irregular hypoechoic line extending through the anterosuperior portion with a comparison view of the normal left side. b The same hypoechoic line seen in image a shown widening under manual hip traction. c T1-weighted Fat Suppressed (FS) Turbo Spin Echo (TSE) MRA sequence in the sagittal plane depicting contrast extension through the articular surface of the anterosuperior labrum. d T1-weighted FS TSE MRA sequence in the coronal plane showing involvement from approximately the 11 o’clock position to the 3 o’clock position

Surgery was performed 3 months after the initial presentation to repair the torn acetabular labrum. The patient was referred for 30 post-surgical physical therapy sessions and maintained compliance. She experienced post-operative complications including progressive hip and groin pain that radiated down the leg in an S1 dermatomal distribution. This was resolved at 12 week post-surgery with a steroid and a 30 day course of anti-inflammatories. At most recent follow-up 36 weeks post-surgery, the patient’s symptoms had resolved.

Case 2

A 24-year-old white female student presented with a complaint of right anterior hip pain. The patient stated the pain began approximately 4 months prior during a softball game in which she slid into home base and collided with the catcher. The patient described a “C-sign” distribution of pain from the anterior to posterior hip which was accompanied by clicking and popping. The patient stated the pain was constant, although worse later in the day and after working out. She rated her pain as a four out of ten on the VNRS. Long-axis distraction and stretching of the hip provided mild and transient relief of symptoms.

The physical examination findings included painful and limited ranges of motion in flexion, internal rotation, and external rotation when compared to the left. Positive orthopedic tests recreating the pain in the right hip included scour, Patrick FABER, Laquerre, and Impingement test. The LEFS Questionnaire (5/20) resulted in a 12.5% disability.

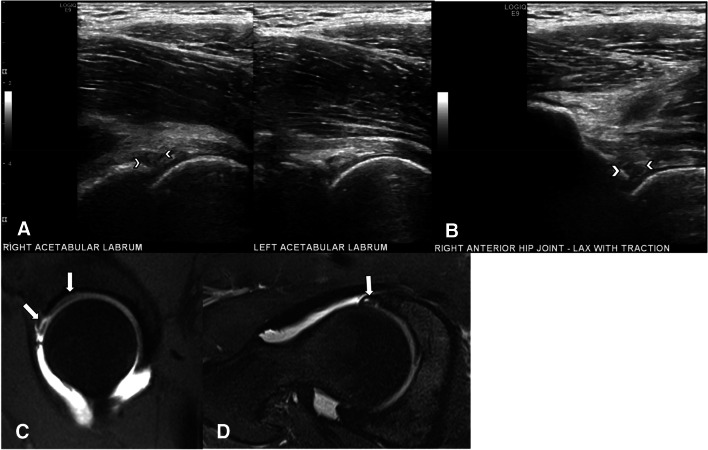

The patient was given the working diagnosis of femoral acetabular impingement. Radiography was waived and US was ordered to evaluate the femoroacetabular labrum. Upon sonographic evaluation, the right labrum was enlarged, heterogeneously hypoechoic, and blunted. Multiple irregular, hypoechoic lines dissected through the anterosuperior portion of the labrum which momentarily widened with manual long-axis hip traction (Fig. 2a, b, and Online Resource 2). The constellation of findings correlated to acetabular labral degeneration with probable anterosuperior tear.

Fig. 2.

Right ALT in a young athletic female. a US of the right hip labrum shows multiple irregular hypoechoic lines dissecting through the anterosuperior portion with a comparison view of the normal left side that is homogenously hyperechoic. b A clear gap of the hypoechoic lines seen in image a is appreciated with the addition of manual hip traction. c T1-weighted FS TSE MRA in the sagittal plane showing high-intensity signal within the right hip labrum from the 12 o’clock to 3 o’clock position. d T2-weighted FS TSE in the axial oblique plane depicting the right labrum as blunted with intrasubstance contrast

An MRA of the right hip was ordered and revealed a high signal intensity within the labrum from approximately the 12 o’clock to 3 o’clock position, consistent with contrast invasion. The triangular fibrocartilage of the anterior labrum was blunted (Fig. 2c, d). These findings confirmed a tear of the right anterior–superior labrum. The patient was referred for an orthopedic consult.

Arthroscopic repair of the ALT occurred 36 weeks after the US examination. In the interim, the patient had been treated with McKenzie hip extension and external rotation exercises at a prescription of one set of ten repetitions every 3 h. The prescribed active care reduced symptoms and delayed surgery to a more convenient time for the patient. At most recent follow-up 3 weeks post-surgery, the patient was experiencing mild pain at the incision sites and was compliant with prescribed post-surgical physical therapy.

Case 3

A 25-year-old male student presented with left anterior hip pain provoked by hip flexion. Four weeks prior to the initial visit, the patient heard a loud pop accompanied by immediate onset of left hip joint pain while performing loaded squats. He described the pain as sharp and rated it at a five out of ten on the VNRS. The pain limited his exercise routine, which typically consisted of 7 days per week of running and weight training.

Upon physical examination, there was tenderness over the left anterior hip joint. The left hip revealed reduced and painful ranges of motion in flexion, extension, and internal rotation. Orthopedic tests that recreated the patients pain included FAIR, FABER, and restricted straight leg raise. The Outcome Assessment Oswestry demonstrated a 38.88% disability.

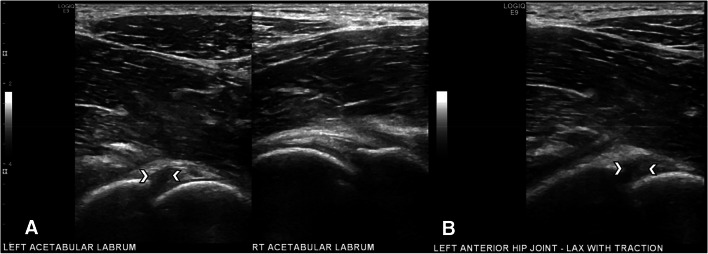

US was ordered to evaluate soft tissues of the left hip, including the acetabular labrum, and radiography was not obtained. The anterosuperior acetabular labrum was enlarged, heterogeneously hypoechoic, and blunted. There were multiple irregular, hypoechoic lines that dissected through the anterosuperior portion of the labrum, at approximately the 12 o’clock to 3 o’clock position, and gapped upon manual axial hip traction (Fig. 3a, b, and Online Resource 3). There was fluid around the labrum and a small joint effusion. The patient was diagnosed with a probable anterosuperior ALT and MRA was recommended.

Fig. 3.

Left ALT in a young athletic male. a US of the left hip shows an enlarged, heterogeneously hypoechoic and blunted morphology to the labrum with a comparison view of the normal left side that is homogenously hyperechoic. There are multiple irregular, hypoechoic lines dissecting through the anterosuperior portion of the left hip labrum. b The same hypoechoic lines seen in image a shown widening under manual hip traction

The patient declined the MRA and opted for a trial of conservative care. The focus was on regaining function and reducing pain by utilizing K-laser therapy and lumbar spinal manipulative therapy three times a week. The patient reduced his workout activities to recumbent biking, walking, and upper body resistance training. After 4 weeks, there was no subjective improvement and the patient sought care through another provider. The patient was diagnosed with a derangement of the left hip as classified by the McKenzie Method. McKenzie hip extension with internal rotation exercises were prescribed. The patient did 20 repetitions 3–5 times per day. At most recent follow-up 28 weeks after US examination, the patient had returned to sport.

Discussion

Diagnosis of ALT based on clinical information alone is a difficult task, requiring imaging to confirm. The first imaging modality utilized is often radiography, although none of the presented cases underwent a radiographic examination. While radiography has little diagnostic value for ALT, it can provide potentially valuable information. For example, it may identify concomitant pathology such as FAI, hip dysplasia, or osteoarthritis [2–4].

The gold standard in ALT diagnosis is arthroscopy. Because it requires a general anesthetic and is only done when surgical intervention is required, imaging modalities are utilized beforehand [9]. Most commonly, MRA is used. This modality enables superb visualization of the labrum due to the high-contrast resolution, the multiplanar property of the scan, and the inclusion of intra-articular contrast that extends the joint capsule [2, 5, 6, 11, 13]. All of these components elevate the sensitivity and specificity to 100% and 80%, respectively [5, 6, 9, 11, 13]. In two of the cases presented, MRA was ordered to confirm the findings from the US examination. In the third case, the patient declined the recommendation for MRA.

Because MRA has contraindications to certain metallic objects and implanted devices and it is not recommended for patients who are claustrophobic, CTA has been utilized to evaluate ALT. Due to the high spatial resolution, multiplanar property, and the inclusion of intra-articular contrast, it is often used as an alternative to MRA for evaluating the hip labrum. The sensitivity and specificity of CTA for ALT is comparable to MRA as high as 92% and 89%, respectively. However, CTA is often foregone as a diagnostic modality due to ionizing radiation [5, 9–11, 13].

An additional diagnostic tool for ALT diagnosis is US. A commonly cited shortcoming is the requirement of an experienced sonographer [10, 14]. The same credentialed sonographer evaluated the labrum of the three cases presented.

Historically, US has not shown competitive diagnostic value for evaluation of pathology of the acetabular labrum. In 2009, Troelsen et al. found a 94% sensitivity in utilizing US for ALT in a small study comparing US to MRA [10]. In 2012, Jin et al. showed slightly less at 82% sensitivity and 60% specificity [15]. Because this modality is non-ionizing, does not require intra-articular administration of contrast material, and is inexpensive, portable, and fast, there is reason to utilize US as an adjunct modality in the diagnosis of ALT.

An advantage of using US is its functional capacity which may improve visualization of suspected pathology in real time [14]. In the cases presented, dynamic joint movements, inherent in the hip protocol, were utilized to evaluate each case. The first case demonstrated approximation and impaction of the CAM-type femoral head–neck junction to the labrum, indicating the CAM as a possible etiology of the visualized ALT. In all three cases, manual long-axis traction was applied to better visualize the labral defects. Long-axis traction in US allowed the labral tear to gap, clarifying the presence of the defect.

While there are no publications describing manual long-axis traction in ALT diagnosis with US, this technique has been used with MRA evaluation of ALT. For MRA with traction, a weighted attachment is utilized to distract the femoroacetabular joint [16–18]. The sensitivity and specificity of MRA with traction were 97% and 86%, respectively, in diagnosing ALT [16]. In the three cases discussed here, traction under US was provided by an assistant manually applying a slow distracting force through the lower extremity, while the patient supine with the knee in full extension. The manual traction was performed at a moderate and non-painful degree that was sustained for a few seconds, while the labrum was evaluated by the sonographer. At that time, the lower extremity was slowly released to its original relaxed position.

When ALT is present on US, a hypoechoic cleft is seen extending through the body of the hip labrum, whereas at MRA, the high signal of the contrast is seen in the cleft. Degeneration is also similar at US and MRA with the shape blunted and intrasubstance cysts that are hypoechoic at US but high signal at MRA [1, 6, 10, 11, 13–15, 18]. When traction is added in either modality, the tear gaps allowing improved visualization. A normal hip labrum on US appears as a homogenous hyperechoic structure with a smoothly and sharply delineated margin. There is no evidence of a hypoechoic cleft inside of the structure. Similarly on MRI, a normal hip labrum will exhibit low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted sequences. The margins of the structure have clean outlines without invasion of contrast [1, 6, 10, 11, 13–15].

In a recent review Draghi et al. showed the important role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of calcific tendinopathy and in its treatment by US percutaneous aspiration guided (US-PICT) [19]. In other cases calcific tendinopathy may be treated conservatively and monitored by ultrasound [20].

A continued advantage MRA and CT hold over US is the capacity to evaluate the entire hip labrum. Because of the deep location and complexity of the targeted anatomy, visualizing the hip labrum is difficult with US, with the exception of the anterior and anterior–superior labrum [21]. Despite this limitation, US should be considered as a reasonable adjunct to MRA or CTA, since up to 92% of ALT occur in the anterosuperior labrum, an area that US is fully capable of evaluating [6, 14, 21–23].

After an ALT is confirmed, management is the next consideration. A patient is a candidate for arthroscopic repair of ALT only after a failed trial of conservative care [24, 25]. Conservative management is less invasive, less expensive, and less prone to complications when compared to surgery. It focuses around pain reduction and functional recovery, whereas surgery has an aim to repair the labral defect. Physical therapy to improve function is generally tailored to each patient to improve range of motion and strengthen the surrounding musculature to restore daily activities and sports participation [1, 24, 25]. In “Case 1”, the patient had a very short trial of care prior to arthroscopy, which confirmed the US and MRA findings.

In cases 2 and 3, the patients opted for a longer course of conservative treatment consisting of McKenzie Method, a system of mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT) commonly utilized in patients diagnosed with spine-related pain. The literature supporting the use of MDT for extremity diagnoses is sparse, but the available research shows consistency in diagnoses among MDT clinicians [26]. May et al. found that most patients could be classified as having a joint derangement, indicating that there will be a rapid response to repeated end range-loaded movement [26]. This was supported by the two cases presented here that were treated with MDT. The patient in “Case 2” proceeded with arthroscopy that confirmed the US and MRA findings, while the patient in “Case 3” had a positive outcome with only conservative care. More research should be done to evaluate the utility of MDT in patients with diagnosed ALT.

Limitations

Out of the three cases, only two proceeded with the MRA recommendation and the gold standard of arthroscopy leaving the third case with less diagnostic certainty. While the results of the two MRA and both arthroscopies proved the US findings, the results cannot be generalized to a larger population, because this is a case series. More research evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of US with manual long-axis traction is needed.

Conclusion

Diagnosing ALT is difficult, requiring a constellation of clinical findings to be supported with imaging findings. MRA remains the imaging modality of choice given its excellent soft-tissue resolution. CTA is a good alternative for patients for whom magnetic resonance is contraindicated. However, the cases presented here contribute to the literature showing the efficacy of US with a novel addition of manual long-axis hip traction as an adjunctive imaging modality in diagnosing ALT.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

No funding was sought or acquired.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No authors of this case series declare any conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration, and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the case series.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Groh MM, Herrera J. A comprehensive review of hip labral tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2007;2(2):105–117. doi: 10.1007/s12178-009-9052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiman MP, Mather RC, Hash TW, Cook CE. Examination of acetabular labral tear: a continued diagnostic challenge. Br J Sports Med. 2013;48(4):311–319. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin RL, Enseki KR, Draovitch P, Trapuzzano T, Philippon MJ. Acetabular labral tears of the hip: examination and diagnostic challenges. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(7):503–515. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia PJ, D’Angelo K, Kettner NW. Posterior, lateral, and anterior hip pain due to musculoskeletal origin: a narrative literature review of history, physical examination, and diagnostic imaging. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(4):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiman MP, Thorborg K, Goode AP, Cook CE, Weir A, Hölmich P. Diagnostic accuracy of imaging modalities and injection techniques for the diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement/labral tear: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(11):2665–2677. doi: 10.1177/0363546516686960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, et al. Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrography in detection and staging. Radiology. 1996;200(1):225–230. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.1.8657916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chopra A, Grainger AJ, Dube B, et al. Comparative reliability and diagnostic performance of conventional 3T magnetic resonance imaging and 1.5T magnetic resonance arthrography for the evaluation of internal derangement of the hip. Eur Radiol. 2017;28(3):963–971. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naraghi A, White LM. MRI of labral and chondral lesions of the hip. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(3):479–490. doi: 10.2214/ajr.14.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christie-Large M, Tapp MJ, Theivendran K, James SL. The role of multidetector CT arthrography in the investigation of suspected intra-articular hip pathology. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(994):861–867. doi: 10.1259/bjr/76751715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Troelsen A, Mechlenburg I, Gelineck J, Bolvig L, Jacobsen S, Søballe K. What is the role of clinical tests and ultrasound in acetabular labral tear diagnostics? Acta Orthop. 2009;80(3):314–318. doi: 10.3109/17453670902988402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perdikakis E, Karachalios T, Katonis P, Karantanas A. Comparison of MR-arthrography and MDCT-arthrography for detection of labral and articular cartilage hip pathology. Skelet Radiol. 2011;40(11):1441–1447. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) Scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Phys Ther. 1999 doi: 10.1093/ptj/79.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee GY, Kim S, Baek S, Jang E, Ha Y. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography in diagnosing acetabular labral tears and chondral lesions. Clin Orthop Surg. 2019;11(1):21. doi: 10.4055/cios.2019.11.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lungu E, Michaud J, Bureau NJ. US assessment of sports-related hip injuries. Radio Graph. 2018;38(3):867–889. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin W, Kim KI, Rhyu KH, et al. Sonographic evaluation of anterosuperior hip labral tears with magnetic resonance arthrographic and surgical correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;31(3):439–447. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmaranzer F, Klauser A, Kogler M, et al. Diagnostic performance of direct traction MR arthrography of the hip: detection of chondral and labral lesions with arthroscopic comparison. Eur Radiol. 2014;25(6):1721–1730. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3534-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishii T, Nakanishi K, Sugano N, Naito H, Tamura S, Ochi T. Acetabular labral tears: contrast-enhanced MR imaging under continuous leg traction. Skelet Radiol. 1996;25(4):349–356. doi: 10.1007/s002560050094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suter A, Dietrich TJ, Maier M, Dora C, Pfirrmann CWA. MR findings associated with positive distraction of the hip joint achieved by axial traction. Skelet Radiol. 2015;44(6):787–795. doi: 10.1007/s00256-015-2099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draghi F, Cocco G, Lomoro P, et al. Non-rotator cuff calcific tendinopathy: ultrasonographic diagnosis and treatment. J Ultrasound. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00393-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cocco G, Ricci V, Boccatonda A, et al. Migration of calcium deposit over the biceps brachii muscle, a rare complication of calcific tendinopathy: Ultrasound image and treatment. J Ultrasound. 2018;21:351–354. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson RE, Walker BF, Young KJ. The accuracy of diagnostic ultrasound imaging for musculoskeletal soft tissue pathology of the extremities: a comprehensive review of the literature. Chiropr Man Ther. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12998-015-0076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blankenbaker DG, Tuite MJ, Keene JS, Rio AM. Labral injuries due to iliopsoas impingement: can they be diagnosed on MR arthrography? Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(4):894–900. doi: 10.2214/ajr.11.8211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orellana C, Moreno M, Calvet J, Navarro N, García-Manrique M, Gratacós J. Ultrasound findings in patients with femoracetabular impingement without radiographic osteoarthritis: a pilot study. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;38(4):895–901. doi: 10.1002/jum.14768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theige M, David S. Nonsurgical treatment of acetabular labral tears. J Sport Rehabil. 2018;27(4):380–384. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2016-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skendzel JG, Philippon MJ. Management of labral tears of the hip in young patients. Orthop Clin N Am. 2013;44(4):477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May S, Rosedale R. A survey of the McKenzie classification system in the extremities: prevalence of mechanical syndromes and preferredloading strategies. Phys Ther. 2012;92:1175–1186. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.