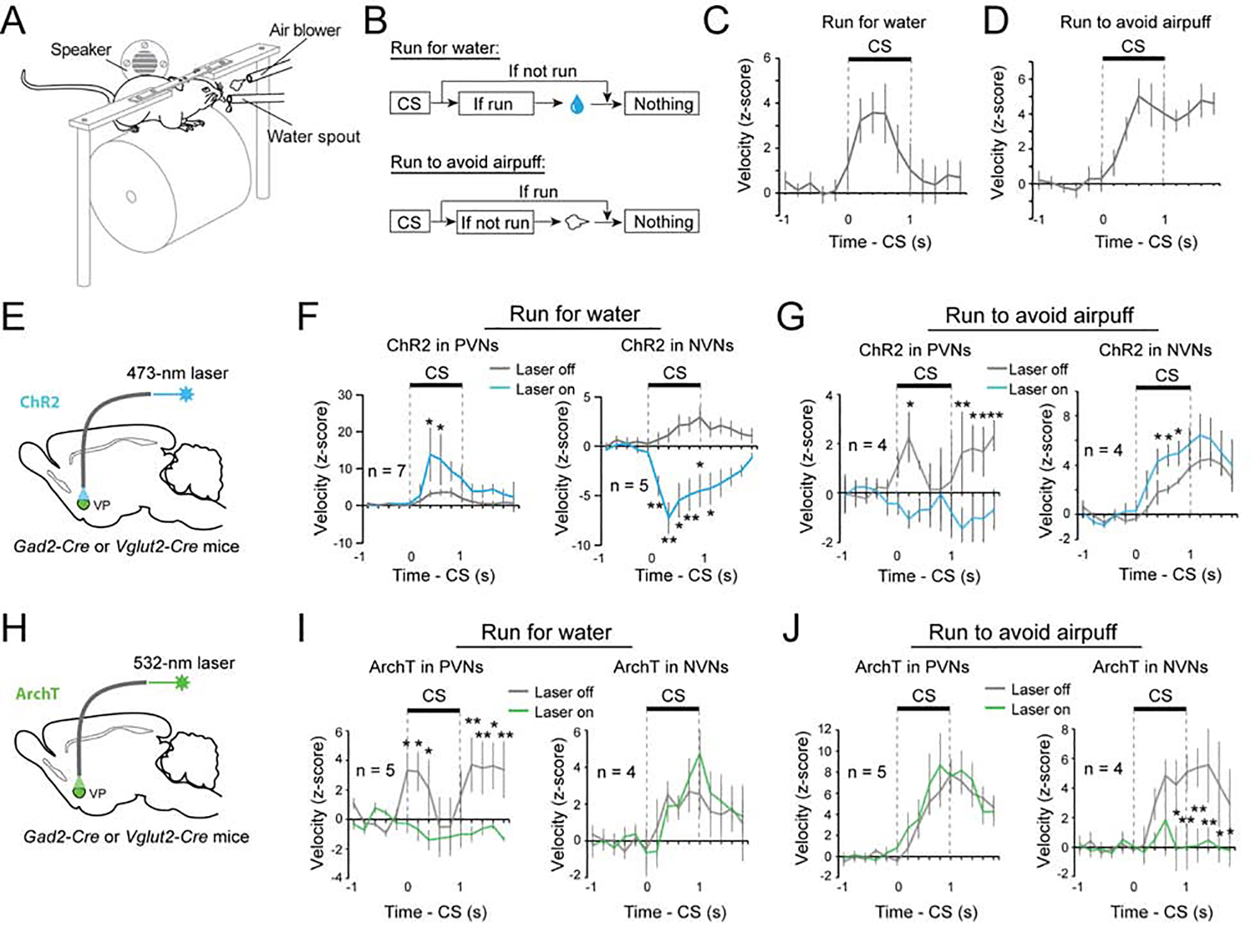

Figure 6. PVNs and NVNs switch roles in controlling actions when motivational context changes.

(A-D) The running tasks. (A) A schematic of the experimental design. (B) Schematics of the experimental procedure. (C) Behavioral performance of mice in the run-for-water task (n = 7). (D) Behavioral performance of mice in the run-to-avoid-air-puff task (n = 4). (E) Schematics of the approach. (F) Left: activation of PVNs increased running for water reward (F(1, 13) = 7.90, p = 0.0055). Right: activation of NVNs decreased running for water reward (F(1, 9) = 132.73, p <0.001). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (G) Left: activation of PVNs decreased running to avoid air puff (F(1,7) = 18.76, P < 0.0001). Right: activation of NVNs increased running to avoid air puff (F(1,7) = 11.61, P = 0.0010). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (H) Schematics of the approach. (I) Left: inhibition of PVNs decreased running for water reward (F(1,9) = 29.283, p < 0.0001). Right: inhibition of NVNs had no effect on running for water reward (F(1, 7) = 0.30, p = 0.59). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (J) Left: inhibition of PVNs had no effect on running to avoid air puff (F(1,9) = 1.30, p = 0.26). Right: inhibition of PVNs decreased running to avoid air puff (F(1, 7) = 22.06, p <0.001). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.