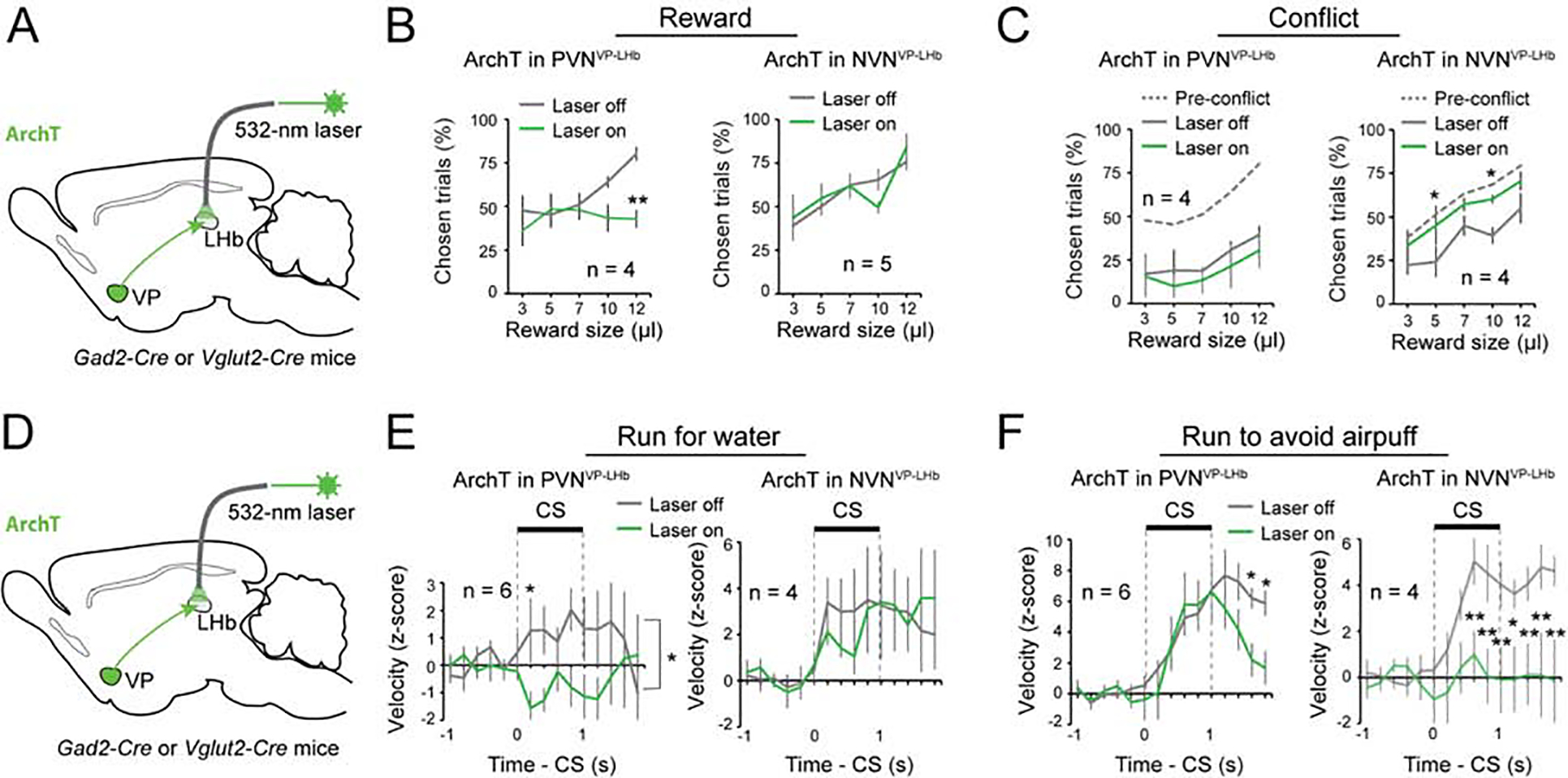

Figure 7. PVNs and NVNs act via the VP-LHb pathway.

(A) A schematic of the approach. (B) Left: inhibition of PVNVP→LHb decreased reward seeking (F(1, 7) = 9.55, p = 0.0043). Right: inhibition of NVNVP→LHb had no effect on reward seeking (F(1, 9) = 0.0041, p = 0.95). **P < 0.01, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (C) Left: inhibition of PVNVP→LHb did not further decrease reward seeking in these mice in the conflict task (F(1, 7) = 1.39, p = 0.25). Right: inhibition of NVNVP→LHb increased reward seeking to pre-conflict levels (F(1, 7) = 13.17, p = 0.0010). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (D) A schematic of the approach. (E) Left: inhibition of PVNVP→LHb decreased running for water reward (F(1, 11) = 8.56, p = 0.004). Right: inhibition of NVNVP→LHb had no effect on running for water reward (F(1, 7) = 0.060, p = 0.81). *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. (F) Left: inhibition of PVNVP→LHb had no effect on running to avoid air puff during the cue, although it induced an earlier termination of the running response after the cue (F(1, 11) = 5.57, p = 0.020). Right: inhibition of NVNVP→LHb decreased running to avoid air puff (F(1, 9) = 40.72, p < 0.0001). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.