Abstract

Background:

Cognitive-frailty (CF), defined as simultaneous presence of cognitive-impairment and physical-frailty, is a clinical symptom in early-stage dementia with promise in assessing the risk of dementia. The purpose of this study was to use wearables to determine the most sensitive digital gait biomarkers to identify CF.

Methods:

Of 121 older adults (age=78.9±8.2years, body mass index=26.6±5.5kg/m2) who were evaluated with a comprehensive neurological exam and the Fried Frailty Criteria, 41 participants (34%) were identified with CF and 80 participants (66%) were identified without CF. Gait performance of participants was assessed under single-task (walking without cognitive distraction) and dual-task (walking while counting backward from a random number) using a validated wearable platform. Participants walked at habitual speed over a distance of 10 meters. A validated algorithm was used to determine steady-state walking. Gait parameters of interest including steady-state gait speed, stride length, gait cycle time, double-support, and gait unsteadiness. In addition, speed and stride length were normalized by height.

Results:

Our results suggest that compared to the group without CF, the CF group had deteriorated gait performances in both single-task and dual-task walking (Cohen’s effect size d=0.42–0.97, p<0.050). The largest effect size was observed in normalized dual-task gait speed (d=0.97, p<0.001). The use of dual-task gait speed improved the area-under-curve (AUC) to distinguish CF cases to 0.76 from 0.73 observed for the single-task gait speed. Adding both single-task and dual-task gait speeds did not noticeably change AUC. However, when additional gait parameters such as gait unsteadiness, stride length, and double-support were included in the model, AUC was improved to 0.87.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that gait performances measured by wearable sensors are potential digital biomarkers of CF among older adults. Dual-task gait and other detailed gait metrics provide value for identifying CF above gait speed alone. Future studies need to examine the potential benefits of gait performances for early diagnosis of CF and/or tracking its severity over time.

Keywords: cognitive-frailty, gait, dual-task walking, older adults, wearable, digital biomarker, digital health, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive decline, cognitive motoric syndrome

Introduction

Dementia causes great stress to our society, health care system, and family caregivers [1–3]. Today 47.5 million people worldwide have dementia, and this number will increase to 75.6 million by 2030 and 135.5 million by 2050 [1]. This “dementia epidemic” [4] creates an urgent need for a robust and rapidly-administered cognitive assessment tool, which is capable of identifying individuals in the earliest stage of cognitive decline and measuring subtle changes in cognitive-motor performance over time [5]. A recent study [6] demonstrated that measures of physical frailty identify individuals with Alzheimer disease (AD) who are at greater risk for cognitive decline and loss of independence. Despite the evidence, cognitive impairment and frailty are rarely assessed, and when assessed, are independently assessed, mainly because conventional cognitive performance assessment tools do not account for motor capacity (an indicator of physical frailty). Conversely, conventional physical frailty assessment tools do not account for cognitive performance.

Identifying persons who experience both motor and cognitive decline, known as cognitive-frailty (CF), a recently recognized symptom in early-stage dementia [4, 7, 6, 8], may have a greater prognostic value in assessing dementia risk. This is because the combination could identify a group in whom gait speed decline is, at least in part, caused by neurodegenerative pathologic conditions of the central nervous system rather than local musculoskeletal problems, such as sarcopenia or osteoarthritis [9–11]. A growing line of research confirmed that CF syndrome is associated with high risks of cognitive decline over time and is a strong predictor of transition to dementia [12–16, 11, 17, 18]. Despite this evidence, motor function and cognitive performance, if assessed, are assessed independently.

AD neuropathology usually starts in the hippocampus and has a profound impact on memory function. However, AD also affects other areas of the brain, including prefrontal areas and its associated cognitive functions, including divided attention, set-shifting, response inhibition, planning, and organizing [19]. The dual-task paradigm (e.g., dual-task walking) is a method for assessing executive function and divided attention performance. It can be used for quantifying both cognitive function and motor capacity, and is sensitive to identify both frailty and mild cognitive impairment [20, 2]. In older adults without the overt disease, greater dual-task “cost” (e.g., the decrement in gait speed induced by performing a cognitive task in parallel with walking) has been linked to worse executive function [21–25], increased incidence of falls [26, 27], more rapid cognitive decline [2, 28, 29], and amyloid deposition [30]. Dual-task performance often declines before memory impairment, highlighting its value as a tool to identify pre-clinical AD diagnosis [23–25].

The spread of wearable digital technologies in healthcare have provided new opportunities to routinely assess gait performance outside of a gait laboratory, including detailed gait metrics rather than simple gait speed calculated by walking distance and stopwatch-measured walking time [31–33]. In this study, we used a validated wearable platform to investigate potential digital biomarkers measured by gait assessment for capturing CF in older adults. We measured detailed gait metrics, including gait speed (normalized by height), stride length (normalized by height), gait cycle time, double support, dual-task cost, and gait unsteadiness in both single-task and dual-task walking tests. We hypothesized that 1) older adults with CF can be identified using gait performance measured by wearables, and specifically dual-task walking will yield a larger effect at discriminating CF than single-task walking and 2) detailed gait metrics measured by the wearable platform can yield better results than using normalized gait speed alone to determine CF.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We recruited older adults (age 65 years or older) with and without cognitive impairment. Older adults with cognitive impairment were recruited from the Memory Disorders Clinic at the Banner Sun Health Research Institute, the Senior Care Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine, and Department of Neurology, Neuropsychology Section at Baylor College of Medicine. Participants with cognitive impairment were clinically diagnosed with either amnestic mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia by board-certified neurologists using comprehensive neurological exams and cognitive screens or comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations. We also recruited cognitively intact older adults within the age range of ± 5 years compared to the cognitively impaired older adults.

Participants were excluded from the study if they were non-ambulatory or had a severe gait impairment (e.g., inability to walk 10 meters independently with or without an assistive device); had major foot problems (e.g., major amputation, severe neuropathy, foot deformity, foot arthritis, foot pain, etc.); had other neurological conditions associated with cognitive impairment (stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, etc.); had any clinically significant medical or psychiatric condition or laboratory abnormality; had severe visual and/or hearing impairment; had changes in psychotropic or sleep medications in the last 6 weeks; or were unwilling to participate.

All participants signed an approved consent form before participation in this study. This study was approved by the local institutional review boards including Baylor College of Medicine (H- 2521) and at the Banner Sun Health Research Institute (1146563).

Demographics and Clinical Information

Demographics and relevant clinical information for all participants were collected using chart-review and self-report, including age, sex, height, weight, use of walking assistance, pain level, activity level, and fall history. Body mass index was calculated based on height and weight. All participants underwent clinical assessments, including Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [34], Fall Efficacy Scale - International (FES-I) [35], Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression (CES-D) [36], and Fried Frailty criteria [37]. The FES-I was used to measure self-report concern about falling. A cutoff of FES-I score of 23 or greater was used to identify participants with high concern about falling [35]. The CES-D scale was used to measure self-reported depression symptoms. A cutoff of CES-D score of 16 or greater was used to identify participants at risk for clinical depression [36].

Determination of Physical Frailty and Cognitive-Frailty

We used Fried Frailty criteria to determine physical frailty [37]. In summary, the presence or absence of physical frailty phenotypes, including unintentional weight loss, weakness (grip strength), slow gait speed (15-foot gait test), self-reported exhaustion, and self-reported low physical activity, were used to assess physical frailty [37]. Participants without phenotype presence were classified as physically robust. Participants with 1 or more positive phenotypes were considered physically frail [37]. In this study, instead of using frailty categories (robust, pre-frail, and frail), we use the term of frailty severity, which is defined by number of phenotypes present [38]. The status of cognitive impairment was confirmed by comprehensive neurological exams and cognitive screens or comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations by board-certified neurologists. The cognitive-intact participants were defined as those without any clinical diagnosis of cognitive impairment and MMSE of 24 or greater [39]. Participants presenting with both cognitive impairment and presence of any physical frailty phenotype were classified into a CF group. Others were classified into a non-CF (NCF) group, which includes all robust participants with or without cognitive impairment.

Gait Test

For all participants, five wearable sensors (LegSys™, BioSensics, Newton, MA, USA) were attached to the lower back, both the left and right thighs and lower shins to quantify gait metrics of interest (Figure 1). Participants were asked to walk with their habitual gait speed for 10 meters without any distraction (single-task walking), using the protocol described in our previous studies [40, 41]. Then they were asked to repeat the test while loudly counting backward from a random two-digit number (dual-task walking: walking + working memory test) [2]. The two walking tests together took less than 1 minute. We used validated algorithms [42–45] to identify the gait initiation and steady state walking. All gait metrics were calculated during the steady-state phase of walking, using validated algorithms [46–49]. All gait metrics of interest were averaged during the entire steady state phase. Normalized gait metrics were calculated by the average gait metrics divided by body height. The evaluated gait metrics in this study included normalized gait speed, normalized stride length, gait cycle time, double support, dual-task cost, gait speed unsteadiness (coefficient of variability of gait speed), and stride length unsteadiness (coefficient of variability of stride length). Dual-task cost was defined as the percentage of normalized gait speed reduction between single-task walking and dual-task walking.

Figure 1:

Gait was assessed using five wireless wearable sensors attached to the lower back, both the left and right thighs and lower shins. We assessed gait under two walking conditions: 1) Single-task walking: Participants were asked to walk with their habitual gait speed for 10 meters without any distraction 2) Dual-task walking Participants were asked to walk with their habitual gait speed for 10 meters, while loudly counting backward from a two-digit random number

Data and Statistical Analysis

All continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. All categorical data were expressed as percentages. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for between-group comparison of continuous demographics and clinical data. Analysis of Chi-square was used for comparison of categorical demographics and clinical data. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed to compare differences between groups for gait metrics, adjusting for gender. A 2-sided p<0.050 was considered to be statistically significant. The effect size for discriminating between groups was estimated using Cohen’s d effect size and represented as d in the Results section. Values were defined as small (0.20–0.49), medium (0.50–0.79), large (0.80–1.29), and very large (above 1.30) [50]. Values less than 0.20 were classified as having no noticeable effect [50]. Linear regression analysis was conducted for the four outcome measures, including MMSE, frailty phenotype, normalized single-task and dual-task gait speeds, to examine correlations between each outcome measure; correlation analyses (Pearson correlation or Spearman’s correlation, depending on data normality) for pairs of these outcome measures were observed. Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to examine the relationship between gait metrics and CF. Four models were built for prospective identification of CF. In Model 1, we used only normalized single-task gait speed as the independent variable. In Model 2, we used only normalized dual-task gait speed as the independent variable. In Model 3, we used both normalized single-task and dual-task gait speed as independent variables. Then, to examine additional values of detailed gait metrics, in Model 4, independent variables included normalized gait speed and gait speed unsteadiness, normalized stride length and stride length unsteadiness, gait cycle time, and double support, in both single-task and dual-task walking. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area-under-curve (AUC) were calculated for the four models. All data and statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) and IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

One hundred and twenty-one participants were recruited. According to their cognitive status and physical frailty status, 41 (34%) participants were classified into the CF group and 80 (66%) participants were classified into the NCF group. As summarized in Table 1, the CF group had a lower prevalence of women (p=0.018) and were taller (p=0.045) than the NCF group. The average MMSE score of the CF group was significantly lower than the NCF group (p<0.001). The CF group had a higher prevalence of high concern about falling (p=0.021), higher CES-D score (p=0.013), and significantly higher prevalence of low activity (p=0.015) than the NCF group. No between-group difference was observed for other characteristics including age, weight, body mass index, prevalence of using walking assistance/aids, pain level, FES-I score, prevalence of at risk for clinical depression, or fall history (p>0.050).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study groups.

| NCF (n=80) | CF (n=41) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 78.7 ± 8.5 | 79.2 ± 7.5 | 0.725 |

| Sex (female), % | 66% | 44% | 0.018 |

| Height, m | 1.63 ± 0.10 | 1.67 ± 0.11 | 0.045 |

| Weight, kg | 71.7 ± 17.3 | 74.1 ± 18.5 | 0.474 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.8 ± 5.8 | 26.2 ± 4.8 | 0.592 |

| Using walking assistance, % | 30% | 17% | 0.123 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| MMSE, units on a scale (max 30) | 29.0 ± 1.3 | 24.7 ± 4.8 | <0.00 |

| Pain level, units on a scale (max 10) | 1.8 ± 4.3 | 1.8 ± 2.2 | 0.996 |

| Concern for fall (FES-I score), units on a | 26.4 ± 10.5 | 22.2 ± 5.8 | 0.069 |

| High concern about falling (FES-I≥23), % | 51% | 29% | 0.021 |

| Depression (CES-D score), units on a scale | 8.2 ± 7.2 | 4.9 ± 6.1 | 0.013 |

| At risk for clinical depression (CES-D≥16), % | 21% | 7% | 0.051 |

| Low activity, % | 15% | 34% | 0.015 |

| Had fall in last 12-month, % | 35% | 32% | 0.717 |

NCF: non cognitive frailty group

CF: cognitive frailty group

FES-I: Fall Efficacy Scale - International

CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression

Significant difference between groups were indicated in bold

As summarized in Table 2, during single-task walking, all gait metrics, except double support, reached statistical significance to identify older adults with CF (d=0.42–0.79, p<0.050), with the largest effect size observed in gait speed unsteadiness (d=0.79, p<0.001). Overall, the effect sizes for between group differences were larger during dual-task walking compared to single-task. All dual-task gait metrics reached statistical significance to identify older adults with CF (d=0.62–0.97, p<0.010), with the largest effect size observed in normalized gait speed (d=0.97, p<0.001). In addition, dual-task cost reached a statistically significant level when compared between the NCF group and the CF group (d=0.68, p=0.001).

Table 2.

Gait performance for groups with and without cognitive frailty.

| NCF (n=80) | CF (n=41) | d * | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Task Walking | ||||

| Normalized Gait Speed, height/s | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.001 |

| Normalized Stride Length, % of height | 71.58 ± 10.89 | 64.09 ± 11.71 | 0.66 | 0.002 |

| Gait Cycle Time, s | 1.14 ± 0.15 | 1.21 ± 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.037 |

| Double Support, % | 24.85 ± 5.21 | 25.60 ± 5.92 | 0.21 | 0.283 |

| Single Task Gait Speed Unsteadiness, % | 5.80 ± 3.64 | 8.96 ± 5.12 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Single Task Stride Length Unsteadiness, % | 4.09 ± 3.19 | 6.75 ± 4.92 | 0.68 | 0.001 |

| Dual Task Walking | ||||

| Normalized Gait Speed, height/s | 0.60 ± 0.15 | 0.45 ± 0.15 | 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Normalized Stride Length, % of height | 71.71 ± 11.74 | 61.21 ± 11.36 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| Gait Cycle Time, s | 1.25 ± 0.19 | 1.46 ± 0.32 | 0.76 | <0.001 |

| Double Support, % | 26.22 ± 5.31 | 29.91 ± 7.52 | 0.62 | 0.002 |

| Dual Task Gait Speed Unsteadiness, % | 6.40 ± 2.62 | 8.56 ± 3.90 | 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Dual Task Stride Length Unsteadiness, % | 3.95 ± 1.82 | 6.10 ± 3.89 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Dual Task Cost, % | 7.70 ± 11.38 | 17.82 ± 16.59 | 0.68 | 0.001 |

NCF: non cognitive frailty group

CF: cognitive frailty group

Results were adjusted by gender

Significant difference between groups were indicated in bold

Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d

Figure 2A color-maps the mutated data to normalized single-task gait speed, whereas Figure 2B color-maps the mutated data to normalized dual-task gait speed. The brighter color (red) presents the higher normalized gait speed, and the darker color (dark blue) presents the lower normalized gait speed. The NCF group is shown in the green region, and the CF group is shown in the pink region. This illustration suggests increasing in frailty severity (higher number of phenotypes) reduces gait speed during both single-task and dual-task conditions. However, only under dual-task condition, cognitive function decline leads to noticeable decline in gait speed. Results also suggest a significant negative correlation between normalized single-task gait speed and frailty severity (r=−0.569, p<0.001). A significant correlation was also observed between normalized single-task gait speed and MMSE score but with lower effect size (r=0.231, p=0.017). Under dual-task gait a similar negative correlation was observed between normalized dual-task gait speed and frailty severity (r=−0.524, p<0.001). However, the correlation between normalized dual-task gait speed and MMSE score showed a higher effect size compared to single-task gait (r=0.297, p=0.002). Moreover, the results showed a significant and strong correlation between normalized single-task and dual-task gait speeds (r=0.864, p<0.001), and a negative correlation between frailty severity and MMSE score (r=−0.231, p=0.029).

Figure 2:

A) A color-coded illustration of MMSE score (x-axis) and number of frailty phenotype presences (y-axis) with color map based on normalized single-task gait speed. With increase in frailty severity, gait speed is reduced (darker blue color). However, deterioration in cognitive function (lower MMSE) does not necessarily map to slower gait speed under single-task walking. B) A similar color-coded grant as Figure 2A, however with color map based on normalized dual-task gait speed. Unlike to single-task, deterioration in cognitive function led to decrease in normalized dual-task gait speed as well. MMSE: Mini-Mental State Exam; CF: Cognitive-frailty; NCF: Non cognitive-frailty

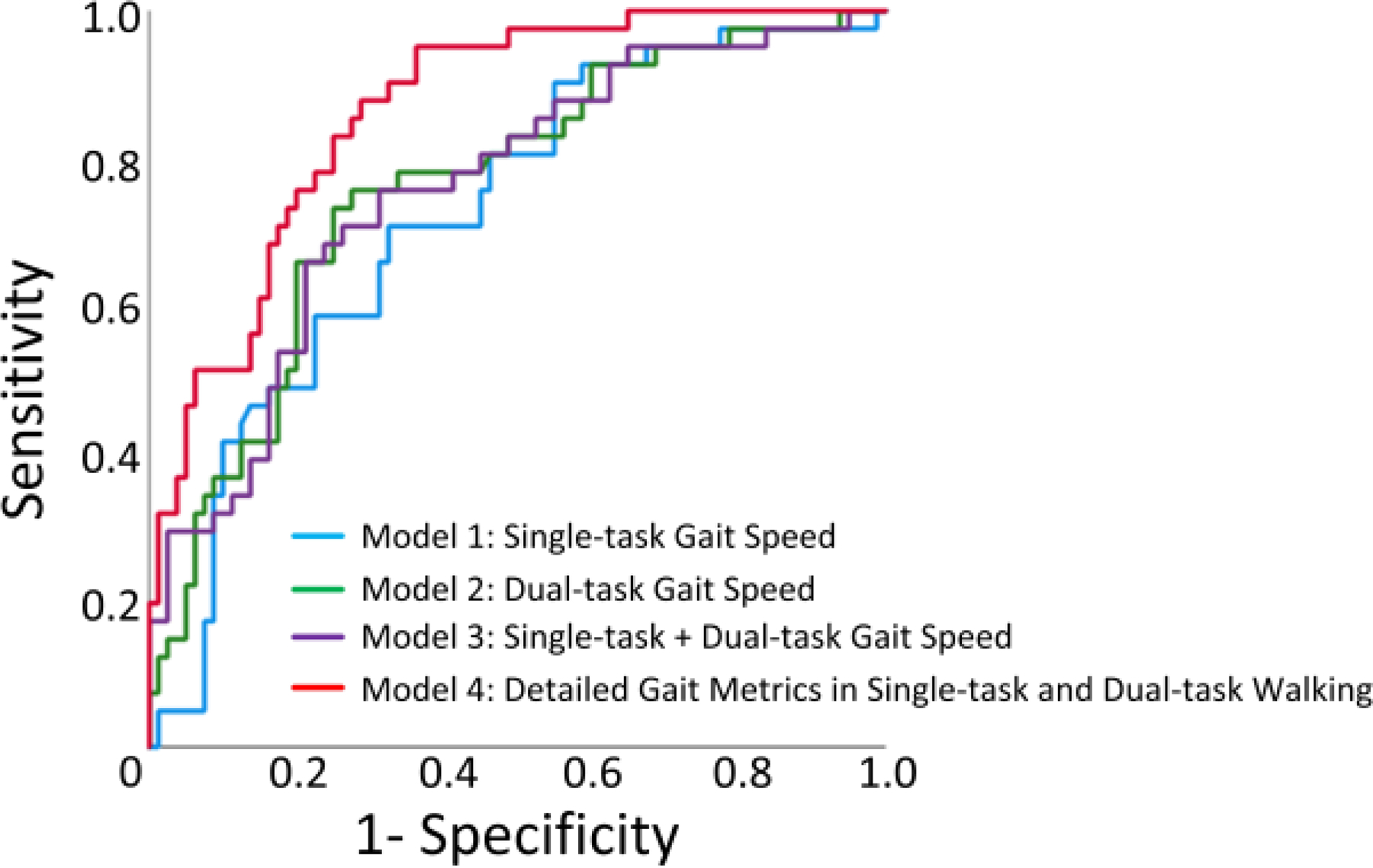

As illustrated in Figure 3, the AUC (accuracy) for distinguishing CF cases were 0.73 (70.2%), 0.76 (70.2%), 0.76 (69.4%), and 0.87 (76%), respectively for the Model 1 (normalized single-task gait speed), Model 2 (normalized dual-task gait speed), Model 3 (normalized single-task + dual-task gait speed) , and Model 4 (normalized gait speed and gait speed unsteadiness + normalized stride length and stride length unsteadiness + gait cycle time + double support, in both single-task and dual-task walking).

Figure 3).

Illustration of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for Model 1 (normalized single-task gait speed), Model 2 (normalized dual-task gait speed), Model 3 (normalized single-task + dual-task gait speed) , and Model 4 (normalized gait speed and gait speed unsteadiness + normalized stride length and stride length unsteadiness + gait cycle time + double support, in both single-task and dual-task walking). While normalized dual-task gait speed improved area under curve (AUC) compared to normalized single-task gait speed, combination of both single-task and dual-task did not noticeably improve AUC. However, addition of other gait metrics during both single-task and dual-task walking (Model 4) noticeably improved AUC.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate potential digital biomarkers using gait performance measures to assess CF in older adults. The results suggest that older adults with CF have deteriorated gait performance compared to those without CF. We confirmed our hypothesis that CF can be identified using gait performance measures, while dual-task walking had a larger observed effect than single-task walking to identify CF. In addition, combining normalized gait speed and gait speed unsteadiness, normalized stride length and stride length unsteadiness, gait cycle time, and double support in both single-task and dual-task walking into the binary logistic regression model enables one to distinguish between older adults with and without CF. This combined model yields relatively higher accuracy compared to normalized gait speed alone (increasing AUC from 0.76 to 0.87 for detection of CF).

In the past decade, there has been an increased interest in identifying and validating biomarkers for early diagnosis and identification of individuals who are at risk of dementia. However, the use of biomarkers has limitations in many settings [51]. For instance, access to neuroimaging is difficult and the cost of biological biomarkers limits their use [52, 51]. Additionally, the highest prevalence and incidence of dementia in the coming years will be observed in low and intermediate income countries, where the accessibility to expensive biomarkers is limited [53]. Hence, there is a need to increase the accessibility to clinical risk assessment of dementia in community-dwelling older populations [8]. Using low-cost wearable technology to determine CF irrespective of setting (e.g., home, small clinic or residential care home) is a promising predictor of dementia in older populations.

There is increasing evidence that impaired motor capacity, such as slow gait, occurs early in dementia and may precede declines in cognitive tests [54–56]. But the effect size of this association is generally modest [14, 18]. Identifying persons who experience both motor decline and cognitive decline, or CF, may have a greater prognostic value in assessing the risk of dementia. In current practice, clinicians typically use resource-intensive methods to assess cognitive function. The current cognitive screening tools have limited ability to detect subtle changes in cognitive performance over time and the accuracy is highly dependent on the examiner’s experience and the patient’s education level [57, 23]. They also do not provide an objective assessment of the impact of cognitive decline on mobility performance. Moreover, while mounting evidence suggests that knowledge of intra-subject performance variation can significantly augment clinical judgment and care, especially in the early stages of AD, the majority of available neuropsychological assessments are ill-suited for repeat testing within relatively short periods due to the effects of practice, patient’s mood, fatigue, and other influences.

Compared with conventional methods, gait assessment is an objective and time-efficient method (usually takes less than 1 minute) to assess functional ability in older adults. A previous systematic review investigating the association between gait and frailty showed that single-task gait speed has the largest effect size to discriminate between frailty subgroups [58]. Previous studies also demonstrated that dual-task gait speed is efficient in discriminating between individuals with different frailty statuses [59] as well as individuals with different cognitive status [60]. In addition, dual-task gait speed is associated with traditional cognitive measurements [61]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using instrumented assessment suggests that mild cognitive impairment related gait changes are most pronounced when subjects are challenged cognitively (dual-task gait) [2]. The results of this study are consistent with these studies. Figure 2A shows that participants with zero or only one positive frailty phenotype had relatively higher single-task walking normalized gait speed (brighter color on the color map). For participants that exhibited higher severity of frailty (those with 3 or 4 positive frailty phenotypes), their normalized single-task gait speeds were reduced (darker color on the color map). However, the normalized single-task gait speed is not sensitive in change along with the decreasing of MMSE score, especially among participants with cognitive impairment. On the other hand, Figure 2B shows that normalized dual-task gait speed is sensitive in reduction along with the decreasing of MMSE score, as well as the increase of presented frailty phenotypes (p<0.001). Among all gait metrics, normalized dual-task gait speed also had the largest effect to discriminate participants with CF (d=0.97, p<0.001).

In this study, instead of using a simple stopwatch, we used a validated wearable platform to measure gait performance. The advantage of using wearable sensors is that we can easily measure detailed gait metrics, such as stride length, gait cycle time, double support, and gait unsteadiness, rather than simple gait speed alone. Although gait speed is still considered the most reliable marker of functional deterioration and physical frailty [62, 63], gait is a complex motor behavior with many measurable facets besides velocity and with an intricate relationship to different aspects of cognition [64]. Previous studies have linked other gait metrics, such as stride length and gait unsteadiness, to cognitive impairment [65, 64, 2]. Our results demonstrate that all gait metrics in dual-task walking can discriminate individuals with CF. In addition, during single-task walking, the gait speed unsteadiness has larger observed effect than normalized gait speed to identify CF. Adding additional gait metrics can increase the power to identify CF in older adults over the use of gait speed alone.

A major strength in this study is using comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations to identify those with cognitive impairment instead of just relying on MMSE to determine those who are at risk of dementia. A recent study suggested that while MMSE has high specificity (94%) to distinguish those with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment from age-matched cognitive intact population, it has poor sensitivity (33%) [25]. Thus, just relying on MMSE may be insufficient to accurately determine those with early stage of dementia. Similarly, in our study we used Fried frailty criteria to determine presence of physical frailty instead of using just gait speed. In the absence of complete phenotype assessment, interpretation of frailty results for prediction of prospective adverse events (e.g., risk of mortality) can be narrow and the predictive power might be reduced [66, 67].

A major limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which could be underpowered for the clinical conclusion. Another limitation of this study is that we did not perform feature selection or other machine learning techniques to find the optimal model for identifying CF. It is possible that some of gait metrics are dependent and may over-train the classifier. We will perform feature selection and Bootstrap techniques [68] in the future study. In this study, we did not have participants presenting with severe cognitive impairment and severe physical frailty simultaneously. Individuals presenting both severe cognitive impairment and severe physical frailty are usually excluded because of other medical conditions they have, as well as because of safety concerns. In this study, the female percentage in the NCF group was significantly higher than in the CF group, which also resulted in a significant difference in height between the two groups. We provided normalized gait speed and stride length by height in the results. We also adjusted the results by gender to provide a fair comparison. In this study, our cohort with cognitive impairment included older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment or cognitive impairment caused by mild dementia. However, cognitive decline may also cause by other neurological disorders such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, etc. Future studies are needed to confirm the observation of this study to determine CF using gait-derived digital metrics among other neurological conditions.

Conclusion

This study suggests that gait metrics measured by wearable sensors during walking tests are potential digital biomarkers of CF among older adults. Results suggest that older adults with CF have deteriorated gait performances compared to those without CF. Dual-task walking has larger observed effect than single-task walking to identify CF. Besides gait speed, adding detailed gait metrics can improve the power to identify CF. We believe that our findings can inform the future design of technologies aiming at screening digital biomarkers of CF among older adults. Future studies are encouraged to use gait metrics to detect onset of CF, as well as to track its severity changes over time. Future studies are also recommended for the potential use of gait metrics to facilitate timely intervention and evaluate treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Noun, Luciana Narvaez, and Anmol Momin for assisting with data collection.

Funding

This research was funded partly by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (award numbers 1R42AG060853–01 and 1R44AG066360–01A1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsor.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

H.Z is now with BioSensics LLC, the company that manufactured the wearable technologies used in this study. H.Z. has however completed the study before joining BioSensics and do not claim any financial conflict of interest relevant to this study.

Statement of Ethics:

All participants signed an approved consent form before participation in this study. This study was approved by the local institutional review boards including Baylor College of Medicine (H-42521) and at the Banner Sun Health Research Institute (1146563).

References

- 1.WHO. World Health Organization. Mental health and older adults 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahureksa L, Najafi B, Saleh A, Sabbagh M, Coon D, Mohler MJ, et al. The Impact of Mild Cognitive Impairment on Gait and Balance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Using Instrumented Assessment. Gerontology 2017;63(1):67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelis E, Gorus E, Beyer I, Bautmans I, De Vriendt P. Early diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia through basic and instrumental activities of daily living: Development of a new evaluation tool. PLoS Med 2017. Mar;14(3):e1002250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, van Kan GA, Ousset PJ, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) international consensus group. J Nutr Health Aging 2013. Sep;17(9):726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks LG, Loewenstein DA. Assessing the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: current trends and future directions. Alzheimers Res Ther 2010. Sep 29;2(5):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelaiditi E, Canevelli M, Andrieu S, Del Campo N, Soto ME, Vellas B, et al. Frailty Index and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease: Data from the Impact of Cholinergic Treatment USe Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016. Jun;64(6):1165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruan Q, Yu Z, Chen M, Bao Z, Li J, He W. Cognitive frailty, a novel target for the prevention of elderly dependency. Ageing research reviews 2015;20:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekhon H, Allali G, Launay CP, Barden J, Szturm T, Liu-Ambrose T, et al. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome, incident cognitive impairment and morphological brain abnormalities: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2019. May;123:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzer R, Epstein N, Mahoney JR, Izzetoglu M, Blumen HM. Neuroimaging of mobility in aging: a targeted review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014. Nov;69(11):1375–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosso AL, Sanders JL, Arnold AM, Boudreau RM, Hirsch CH, Carlson MC, et al. Multisystem physiologic impairments and changes in gait speed of older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015. Mar;70(3):319–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doi T, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, Makino K, et al. Combined effects of mild cognitive impairment and slow gait on risk of dementia. Exp Gerontol 2018. Sep;110:146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verghese J, Ayers E, Barzilai N, Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Holtzer R, et al. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: Multicenter incidence study. Neurology 2014. Dec 9;83(24):2278–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beauchet O, Allali G, Annweiler C, Verghese J. Association of Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome With Brain Volumes: Results From the GAIT Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016. Aug;71(8):1081–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beauchet O, Annweiler C, Callisaya ML, De Cock AM, Helbostad JL, Kressig RW, et al. Poor Gait Performance and Prediction of Dementia: Results From a Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016. Jun 1;17(6):482–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chhetri JK, Chan P, Vellas B, Cesari M. Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome: Predictor of Dementia and Age-Related Negative Outcomes. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017;4:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doi T, Shimada H, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Verghese J, Suzuki T. Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome: Association with Incident Dementia and Disability. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;59(1):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verghese J, Wang C, Bennett DA, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Ayers E. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and predictors of transition to dementia: A multicenter study. Alzheimers Dement 2019. Jul;15(7):870–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian Q, Resnick SM, Mielke MM, Yaffe K, Launer LJ, Jonsson PV, et al. Association of Dual Decline in Memory and Gait Speed With Risk for Dementia Among Adults Older Than 60 Years: A Multicohort Individual-Level Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020. Feb 5;3(2):e1921636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Li X, Wu W, Li Z, Qian L, Li S, et al. Atrophic Patterns of the Frontal-Subcortical Circuits in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One 2015;10(6):e0130017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwenk M, Grewal GS, Honarvar B, Schwenk S, Mohler J, Khalsa DS, et al. Interactive balance training integrating sensor-based visual feedback of movement performance: a pilot study in older adults. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2014. Dec 13;11:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubost V, Kressig RW, Gonthier R, Herrmann FR, Aminian K, Najafi B, et al. Relationships between dual-task related changes in stride velocity and stride time variability in healthy older adults. Hum Mov Sci 2006. Jun;25(3):372–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubost V, Annweiler C, Aminian K, Najafi B, Herrmann FR, Beauchet O. Stride-to-stride variability while enumerating animal names among healthy young adults: result of stride velocity or effect of attention-demanding task? Gait Posture 2008. Jan;27(1):138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou H, Sabbagh M, Wyman R, Liebsack C, Kunik ME, Najafi B. Instrumented Trail-Making Task to Differentiate Persons with No Cognitive Impairment, Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer Disease: A Proof of Concept Study. Gerontology 2017;63(2):189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Park S. Effects of a priority-based dual task on gait velocity and variability in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J Exerc Rehabil 2018. Dec;14(6):993–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toosizadeh N, Ehsani H, Wendel C, Zamrini E, Connor KO, Mohler J. Screening older adults for amnestic mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease using upper-extremity dual-tasking. Sci Rep 2019 Jul 29;9(1):10911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman T, Mirelman A, Giladi N, Schweiger A, Hausdorff JM. Executive control deficits as a prodrome to falls in healthy older adults: a prospective study linking thinking, walking, and falling. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010. Oct;65(10):1086–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goncalves J, Ansai JH, Masse FAA, Vale FAC, Takahashi ACM, Andrade LP. Dual-task as a predictor of falls in older people with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Braz J Phys Ther 2018. Sep - Oct;22(5):417–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauchet O, Launay CP, Sekhon H, Barthelemy JC, Roche F, Chabot J, et al. Association of increased gait variability while dual tasking and cognitive decline: results from a prospective longitudinal cohort pilot study. Geroscience 2017. Aug;39(4):439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montero-Odasso MM, Sarquis-Adamson Y, Speechley M, Borrie MJ, Hachinski VC, Wells J, et al. Association of Dual-Task Gait With Incident Dementia in Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results From the Gait and Brain Study. JAMA Neurol 2017. Jul 1;74(7):857–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadkarni NK, Lopez OL, Perera S, Studenski SA, Snitz BE, Erickson KI, et al. Cerebral Amyloid Deposition and Dual-Tasking in Cognitively Normal, Mobility Unimpaired Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017. Mar 1;72(3):431–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H, Al-Ali F, Rahemi H, Kulkarni N, Hamad A, Ibrahim R, et al. Hemodialysis impact on motor function beyond aging and diabetes—objectively assessing gait and balance by wearable technology. Sensors 2018;18(11):3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang GE, Zhou H, Varghese V, Najafi B. Characteristics of the gait initiation phase in older adults with diabetic peripheral neuropathy compared to control older adults. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2019. Dec 23;72:155–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling E, Lepow B, Zhou H, Enriquez A, Mullen A, Najafi B. The impact of diabetic foot ulcers and unilateral offloading footwear on gait in people with diabetes. Clinical Biomechanics 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, et al. Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Archives of neurology 2008;65(7):963–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delbaere K, Close JC, Mikolaizak AS, Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Lord SR. The falls efficacy scale international (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age and ageing 2010;39(2):210–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. American journal of epidemiology 1977;106(3):203–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2001;56(3):M146–M57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Razjouyan J, Najafi B, Horstman M, Sharafkhaneh A, Amirmazaheri M, Zhou H, et al. Toward Using Wearables to Remotely Monitor Cognitive Frailty in Community-Living Older Adults: An Observational Study. Sensors (Basel) 2020. Apr 14;20(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pezzotti P, Scalmana S, Mastromattei A, Di Lallo D, Progetto Alzheimer Working G. The accuracy of the MMSE in detecting cognitive impairment when administered by general practitioners: a prospective observational study. BMC Fam Pract 2008. May 13;9:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Najafi B, Khan T, Fleischer A, Wrobel J. The impact of footwear and walking distance on gait stability in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 2013;103(3):165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zahiri M, Chen KM, Zhou H, Nguyen H, Workeneh BT, Yellapragada SV, et al. Using wearables to screen motor performance deterioration because of cancer and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) in adults - Toward an early diagnosis of CIPN. J Geriatr Oncol 2019. Nov;10(6):960–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindemann U, Najafi B, Zijlstra W, Hauer K, Muche R, Becker C, et al. Distance to achieve steady state walking speed in frail elderly persons. Gait Posture 2008. Jan;27(1):91–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Najafi B, Miller D, Jarrett BD, Wrobel JS. Does footwear type impact the number of steps required to reach gait steady state?: an innovative look at the impact of foot orthoses on gait initiation. Gait Posture 2010. May;32(1):29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Najafi B, Khan T, Fleischer A, Wrobel J. The impact of footwear and walking distance on gait stability in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2013. May-Jun;103(3):165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang GE, Zhou H, Varghese V, Najafi B. Characteristics of the gait initiation phase in older adults with diabetic peripheral neuropathy compared to control older adults. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2020. Feb;72:155–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aminian K, Najafi B, Büla C, Leyvraz P-F, Robert P. Spatio-temporal parameters of gait measured by an ambulatory system using miniature gyroscopes. Journal of biomechanics 2002;35(5):689–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aminian K, Trevisan C, Najafi B, Dejnabadi H, Frigo C, Pavan E, et al. Evaluation of an ambulatory system for gait analysis in hip osteoarthritis and after total hip replacement. Gait Posture 2004. Aug;20(1):102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Najafi B, Helbostad JL, Moe-Nilssen R, Zijlstra W, Aminian K. Does walking strategy in older people change as a function of walking distance? Gait Posture 2009. Feb;29(2):261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Najafi B, Khan T, Wrobel J. Laboratory in a box: wearable sensors and its advantages for gait analysis. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011;2011:6507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belleville S, LeBlanc AC, Kergoat MJ, Calon F, Gaudreau P, Hebert SS, et al. The Consortium for the early identification of Alzheimer’s disease-Quebec (CIMA-Q). Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2019. Dec;11:787–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Handels RLH, Wimo A, Dodel R, Kramberger MG, Visser PJ, Molinuevo JL, et al. Cost-Utility of Using Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers in Cerebrospinal Fluid to Predict Progression from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;60(4):1477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Jager CA, Msemburi W, Pepper K, Combrinck MI. Dementia Prevalence in a Rural Region of South Africa: A Cross-Sectional Community Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;60(3):1087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camicioli R, Howieson D, Oken B, Sexton G, Kaye J. Motor slowing precedes cognitive impairment in the oldest old. Neurology 1998. May;50(5):1496–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buracchio T, Dodge HH, Howieson D, Wasserman D, Kaye J. The trajectory of gait speed preceding mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2010. Aug;67(8):980–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Savica R, Cha R, Drubach DI, Christianson T, et al. Assessing the temporal relationship between cognition and gait: slow gait predicts cognitive decline in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013. Aug;68(8):929–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin F, Vance DE, Gleason CE, Heidrich SM. Caring for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: an update for nurses. J Gerontol Nurs 2012. Dec;38(12):22–35; quiz 36–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwenk M, Howe C, Saleh A, Mohler J, Grewal G, Armstrong D, et al. Frailty and technology: a systematic review of gait analysis in those with frailty. Gerontology 2014;60(1):79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guedes RC, Dias RC, Pereira LS, Silva SL, Lustosa LP, Dias JM. Influence of dual task and frailty on gait parameters of older community-dwelling individuals. Braz J Phys Ther 2014. Sep-Oct;18(5):445–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maquet D, Lekeu F, Warzee E, Gillain S, Wojtasik V, Salmon E, et al. Gait analysis in elderly adult patients with mild cognitive impairment and patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease: simple versus dual task: a preliminary report. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2010. Jan;30(1):51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doi T, Shimada H, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Uemura K, Anan Y, et al. Cognitive function and gait speed under normal and dual-task walking among older adults with mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurol 2014. Apr 1;14:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parentoni AN, Mendonca VA, Dos Santos KD, Sa LF, Ferreira FO, Gomes Pereira DA, et al. Gait Speed as a Predictor of Respiratory Muscle Function, Strength, and Frailty Syndrome in Community-Dwelling Elderly People. J Frailty Aging 2015;4(2):64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Syddall HE, Westbury LD, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Self-reported walking speed: a useful marker of physical performance among community-dwelling older people? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015. Apr;16(4):323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, Xue X. Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007. Sep;78(9):929–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheridan PL, Solomont J, Kowall N, Hausdorff JM. Influence of executive function on locomotor function: divided attention increases gait variability in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2003. Nov;51(11):1633–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013. Sep;61(9):1537–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Theou O, Cann L, Blodgett J, Wallace LM, Brothers TD, Rockwood K. Modifications to the frailty phenotype criteria: Systematic review of the current literature and investigation of 262 frailty phenotypes in the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Ageing research reviews 2015. May;21:78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee H, Joseph B, Enriquez A, Najafi B. Toward Using a Smartwatch to Monitor Frailty in a Hospital Setting: Using a Single Wrist-Wearable Sensor to Assess Frailty in Bedbound Inpatients. Gerontology 2018;64(4):389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]