Abstract

The multiredox reactivity of bioinorganic cofactors is often coupled to proton transfers. Here we investigate the structural, thermochemical, and electronic structure of ruthenium-amino/amido complexes with multi- proton-coupled electron transfer reactivity. The bis(amino)ruthenium(II) and bis(amido)ruthenium(IV) complexes [RuII(bpy)(en*)2]2+ (RuII-H0) and [RuIV(bpy)(en*-H2)2]2+ (RuIV-H2) interconvert reversibly with the transfer of 2e−/2H+ (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine, en* = 2,3-diamino-2,3-dimethylbutane). X-ray structures allow correlations between the structural and electronic parameters, and the thermochemical data of the 2e−/2H+ multi-square grid scheme. Redox potentials, acidity constants and DFT calculations reveal potential intermediates implicated in 2e−/2H+ reactivity with organic reagents in non-protic solvents, which shows a strong inverted redox potential favouring 2e−/2H+ transfer. This is suggested to be an attractive system for potential one-step (concerted) transfer of 2e−and 2H+ due to the small changes of the pseudo-octahedral geometries and the absence of charge change, indicating a relatively small overall reorganization energy.

Keywords: Amido complexes, Electronic structure, Multiredox, PCET, Ruthenium complexes

Graphical Abstract

Analysis of structural and electronic configurations reveal how energetics favors 2e−/2H+ transfers with potential inversion in a model Ruthenium bis-amido complex. These studies bring tools for further understanding of the increased complexity of multi-PCET reactions.

Introduction

Electron and proton transfers are central to energy conversion and storage, catalysis, and chemical synthesis for a wide range of biological processes and technological developments.1 The importance of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions has inspired numerous studies,2-3 most of which focus on mechanistic and thermochemical aspects of one-electron/one-proton (1e−/1H+) transfers.1-4 However, transfer of multiple electrons and protons is typically required. It would be very advantageous to have concerted 2e−/2H+ transfers to avoid formation of open-shell, high energy organic radical intermediates, but such processes are quite rare.5 One approach to such multi-PCET processes could be the development of (bio)-inorganic compounds able to sustain multiple-redox states within a small range of redox potentials.

Correlations among structure, electronic configuration, and thermochemistry using model systems have revealed the parameters that control the mechanism and rates of 1e−/1H+ PCET reactions.6 However, studies expanding into multi-PCET systems are sparce,5,7 largely due to their inherent higher complexity.8 Revealing the parameters that control multi-PCET reactivity holds promise to understand and control processes of significant biological and technological importance, such as H2O oxidation, CO2 reduction and nitrogen fixation.

Multi-PCET reactions are generally considered to require significant reorganizations from the initial donor to the final acceptor states.5,7 However, ways in which proton transfer might assist stabilization of charge states, reduction of activation energies, and redox potential inversion remain unclear.1b,e

Metal complexes featuring amine/imine/amido/imido/nitride complexes interconvert by transfer of protons and redox equivalents. The wide reactivity of this extensive family of complexes awards them unique catalytic properties.9 The ruthenium congeners are highly versatile, allowing isolation of complexes ranging from amine to nitride ligands. Ru amido/nitride complexes are, however, more reactivate compared to analogue Os complexes leading to a smaller number of complexes isolated and characterized.8c,f General similarities with Ru aquo/hydroxo/oxo complexes underlines the potential to access a wide range of reactivity based on their multi-PCET chemistry.10 For example, RuV-N amido complexes have been proposed as reactive electrophiles enabling water nucleophilic attack (WNA) as a critical step in water oxidation.11-13

Chiu et al. showed the 2e−/2H+ chemically reversible interconversion of RuII-amine to RuIV-amido in aqueous media.14 Central to chemical stability of this couple is the use of two en* ligands (en* = 2,3-diamino-2,3-dimethylbutane) in which the methyl groups prevent α-CH elimination and the two amido groups stabilize the RuIV redox state.15 Stable RuIV-amido complexes bear clear parallels to chemistry of Ru=O species, thus highlighting potential similarities in their multi-PCET reactivity.16

We recently reported outer-sphere 2e−/2H+ reactions that form and cleave a variety of O─H, N─H, S─H, and C─H bonds using the RuII-amine/RuIV-amido couple with [RuII(bpy)(en*)2]2+ (RuII-H0) and [RuIV(bpy)(en*-H)2]2+ (RuIV-H2) (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine).17 IR and MS cryogenic studies revealed hydrogen bonding interactions likely to be critical for the formation of the association complex required for 2e−/2H+ transfers.18

Here we report on the combined analysis of X-Ray and calculated structures, thermochemical data, and electronic configuration from DFT computations. This allowed us to identify species involved in the 2e−/2H+ interconversion of RuII-H0/RuIV-H2 couple with spectroscopic signatures and energies involved, highlighting the preferences for a 2e−/2H+ reaction.

Results and Discussion

Structures.

X-ray crystal structures of both species of the RuII-H0 /RuIV-H2 couple with PF6− counterions were successfully determined (Table 1). For simplicity and for clarity, the nomenclature for each species in the manuscript includes the oxidation state and the number of protons subtracted from the amino groups, as was stated by Chiu et. al.14 The crystal structure for RuIV-H2 with [ZnBr4]2− counterions was previously reported,14 and there are no significant differences from ours. The X-ray structure of RuII-H0 is shown in Figure 1. Both structures crystalized in the monoclinic system, with an acetone molecule also shown in the packing. Thermal distortions at the PF6− anion are also observed.

Table 1.

X-ray Crystallographic Data for [RuII-H0](PF6)2 and [RuIV-H2](PF6)2.

| [RuII-H0](PF6)2.3C3H6O | [RuIV-H2](PF6)2.0.5C3H6O | |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C47H86F24N12OP4Ru2 | C31H56F12N6O3P2RU |

| Formula weight | 1617.30 | 951.83 |

| Temperature | 100(2) K | 100(2) K |

| Wavelength | 0.71073 Å | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | C 2/c | P21/n |

| A | 33.9091(5) Å | 11.5969(3) Å |

| B | 9.7830(2) Å | 14.7299(4) Å |

| C | 20.4460(3) Å | 25.6697(7) Å |

| β | 105.048(1)° | 91.733(2)° |

| Volume | 6550.02(19) Å3 | 4382.9(2) Å3 |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| d calcd | 1.640 Mg/m3 | 1.442 Mg/m3 |

| μ | 0.673 mm−1 | 0.519 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 3296 | 1960 |

| Crystal size | 0.30 x 0.15 x 0.10 mm3 | 0.16 x 0.13 x 0.10 mm3 |

| Θ range | 2.06 to 26.37° | 1.91 to 28.32° |

| Index ranges | −42 ≤ h ≤ 42 | −15 ≤ h ≤ 15 |

| −12 ≤ k ≤ 12 | −19 ≤ k ≤ 19 | |

| −25 ≤ I ≤ 25 | −34 ≤ I ≤34 | |

| Reflns collected | 57226 | 145961 |

| Indt reflections | 6600 [R(int) = 0.0256] | 10792 [R(int) = 0.0645] |

| Completeness to theta = 25.00° | 98.4 % | 99.3 % |

| Max. and min. transmission | 0.9358 and 0.8236 | 0.9499 and 0.9216 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 6600 / 0 / 471 | 10792 / 0 / 510 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.171 | 1.124 |

| Final R indices [I>2sigma(I)] | R1 = 0.0595, wR2 = 0.1118 | R1 = 0.0663, WR2 = 0.1492 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0654, wR2 = 0.1162 | R1 = 0.0899, WR2 = 0.1640 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole | 0.967 and −1.497 e.Å−3 | 1.313 and −0.952 e.Å−3 |

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagram for complex [RuII-H0](PF6)2.

A comparison of the X-ray structures of RuII-H0 and RuIV-H2 shows small structural distortions upon 2e−/2H+ transfer. The primary reorganizations are centred at the N-Ru-N bonds and angles. The observed structural distortions are in general smaller than those observed for the interconversion of RuII-OH2 to RuIV=O.19 Table 2 shows selected bond lengths and angles undergoing the most significant distortions for the RuII-H0 / RuIV-H2 couple.

Table 2.

Comparison of most distorted bond lengths between [RuII-H0](PF6)2 and [RuIV-H2](PF6)2.

| bond | RuII-H0 | RuIV-H2 |

|---|---|---|

| C-N in en* | 1.50 – 1.52 | 1.50 |

| C-N in en*-H | --- | 1.46 – 1.49 |

| C-C in en* | 1.55 | 1.56 – 1.58 |

| Ru-N bpy | 2.05 | 2.16 |

| Ru-N amine | 2.11 – 2.14 | 2.11 |

| Ru-N amido | --- | 1.86 – 1.87 |

| N4-RU-N6 | 90.1 | 105.7 |

The most significant structural changes between RuII-H0 and RuIV-H2 are the Ru─N bond distances and angles for the nitrogen atoms trans to the bpy ligand, where the −NH2 is converted to −NH (RuII-amine → RuIV-amido). The Ru─N bond is shortened after oxidation from ~2.13 Å to ~1.86 Å, forming a Ru─N bond with distances in the range of related Ru─N double bonds.13 Strengthening of the Ru─N bond on the en* ligand occurs concomitant with weakening (lengthening) of the Ru─N bond to the bpy ligand, from 2.05 Å to 2.16 Å from RuII-H0 to RuIV-H2. These rearrangements are consistent with a trans effect due to the increased π-donor ability of the amido ligand in RuIV-H2, and rehybridization of the N-amido towards sp2 indicated by the Ru─N─C angle ~120°.

Computed structures of potential intermediates of a stepwise 2e−/2H+transfer (vide infra, and SI) show gradual distortions of the Ru-N-H and Ru-N(bpy) bonds and N(amine/amido)-Ru-N(amine/amido) angle. Table S12 summarizes the main computed bond lengths and angles for intermediates and highlights important structural differences.

Electrochemistry.

Cyclic voltammograms of both complexes were measured in dry MeCN showing irreversible electrochemical features. In presence of triflic acid (TfOH), however, the RuIII-H0/RuII-H0 couple becomes chemically reversible with E½ = 260 mV vs Fc+/0 in MeCN TBAPF6 0.1M (Figure S8). The required presence of TfOH (pKa = 2.6 in MeCN)20 indicates that amine group becomes strongly acidic upon oxidation. The [Ru(bpy)(NH3)4]2+ complex has a similar E½ = 0.13 V vs. Fc+/0.21 Reduction of complex RuIV-H2 shows a chemically reversible process at E½ = −1190 mV vs Fc+/0 in MeCN but only when measured at high scan rates (2000 mVs−1). This is assigned to the couple RuIV-H2/RuIII-H2. The need for fast scan rates or added acid show that the irreversibility typically observed in both that cases is the result of an EC mechanism, where the chemical step agrees with the protonation/deprotonation of the formed species. In the case of the oxidation of RuII-H0 in the presence of 2-Cl-aniline an ECE mechanism is evidenced, suggesting that the pKa for RuIII-H0 should be ≦ 7.8 in MeCN (Figure S9). Also, a second reduction potential appears at a ~150 mV lower value. This implies that RuIV-H1/ RuIII-H1 has E° ~100 mV vs. Fc+/0.

Spectrophotometric Titrations.

Titrations of RuII-H0 with bases of different pKa show that RuII-H0 is a very weak acid. Spectrophometric titrations of RuII-H0 in strong basic aqueous solution didn’t show any evidence of deprotonation up to pH 14. Spectrophotometric titration in MeCN with additions of more than 1000 eq of DBU indicate that its pKa value is over 27.3 (Figure S4). Titration with P2-t-Bu-phosphazene (pKa = 33.5 in MeCN),22 gives very well defined isosbestic points. Fitting of data shows a small component that could be assigned to some decomposition under these strong basic conditions (see details in sup info). Otherwise, analysis of data resolved a very clear titration and after mathematical analysis fit of data results in pKa = 33.1 ± 0.2 for: (RuII-H0 ⇌ RuII-H1 + H+) in MeCN (Eq 1).

| (1) |

MLCT transitions at 380 and 519 nm shift to lower energies at 405 and 580 nm in the deprotonated species (RuII-H1) with isosbestic points at 390, 485 and 542 nm (Figure 2). This result suggests a strong π-antibonding interaction between the filled ruthenium d-t2g and amide π nitrogen orbitals, making this deprotonation very unfavourable. The reported pKa dependence of the electrochemistry in water showed no deprotonation of RuII-H0 up to pH 7, and an aqueous pKa of ~2.0 for RuIII-H0 ⇌ RuIII-H1 + H+ (Eq 2).14

| (2) |

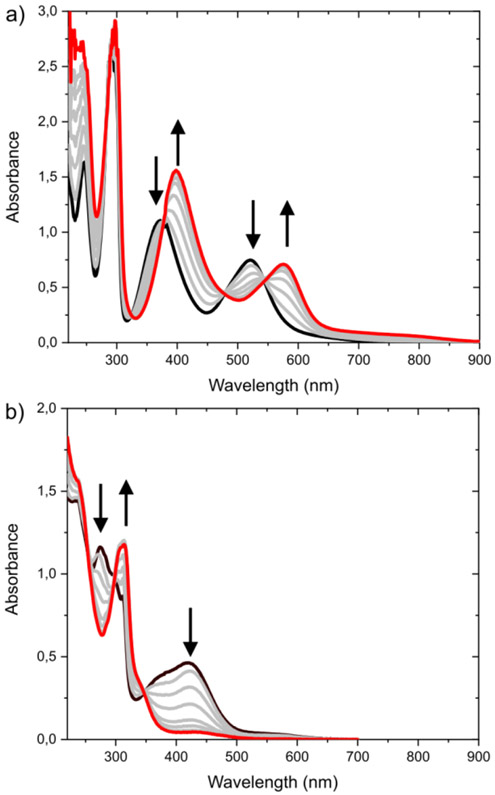

Figure 2.

a) Titration of RuII-H0 with P2-t-Bu-phosphazene (pKa = 33.5) in MeCN. b) Titration of RuIV-H2 With triflic acid (pKa = 2.6) in MeCN.

Titrations of RuIV-H2 with different acids indicate a very low pKa value. Titration in water with sulfuric acid shows weak changes suggesting a pKa < 0. In MeCN, the titration of RuIV-H2 with 2,6-dimethoxy-pyridinium and 2,6-dichloro-anilinum (pKa 7.6423 and 5.0724 respectively), indicated a pKa < 3. Addition of TfOH in MeCN shows complete and reversible conversion. The protonated species (RuIV-H1) has electronic transitions at higher energies (below 350 nm) with concomitant depletion of transitions of RuIV-H2 at 420 nm (Figure 2). This TfOH titration gave a pKa = 1.5 ± 0.2 for (RuIV-H2 + H+ ⇌ RuIV-H1 (Eq 3), which is slightly more acidic than TfOH (pKa = 2.6)20 in MeCN. Also, here protonation of the nitrogen means that the Ru ⚍ N bond is very stable and only a strong acid can break it.

| (3) |

Calculations of electronic structure and electronic spectra.

DFT and TD-DFT computations were used to gain insights into the electronic structure and thermochemical data for each accessible redox or protonation intermediate in a grid square scheme for 2e−/2H+ transfers.

Optimization of structures of RuII-H0 and RuIV-H2 show excellent agreement with both crystallographic structures. A comparison of functionals resulted on the hybrid functional B3LYP to yield the best correlation between calculated electronic transitions and experimental absorption spectra. Likewise, the exchange-correlation BPV86 functional yielded the best agreement with the experimental thermochemical data used for benchmarking for the square diagrams of the complexes investigated here (see below) and of [RuII/III(acac)2(py-am(H))]+/0/− complexes (acac = β-diketonato, and py-im(H) = 2-(2’-pyridyl)imidazole)25-27 (Table S11).

TD-DFT calculations reproduce well the experimental UV-vis spectra of RuII-H0 and RuIV-H2 (Figure 3). For RuII-H0, the lowest electronic transition is MLCT dπ(Ru)→π1*(bpy), followed by MLCT dπ(Ru)→π2*(bpy) and IL π→π1*(bpy). In the frontier molecular orbitals (FMO’s), the LUMO, LUMO+1, LUMO+2, and LUMO+4 of RuII-H0 have major contributions from the bpy π* orbitals; whereas, LUMO+3, and LUMO+5 have major contribution from the antibonding Ru d-eg orbitals, (dz2, dx2y2). HOMO, HOMO-1, and HOMO-2 are the nonbonding Ru d-t2g orbitals, (dxy, dyz, dxz); whereas HOMO-4 corresponds to bpy π orbitals. For RuIV-H2, the lowest electronic transition is LMCT pN→dπ*(Ru ⚍ N) from the equatorial NH’s trans to bpy, followed by MLCT dπ(Ru)→π1*(bpy) and IL π→π1*(bpy). The LUMO has major contributions from the dπ(Ru ⚍ N) (π*) orbital; whereas LUMO+1, LUMO+2, and LUMO+3 are bpy (π*) orbitals. The HOMO-4, HOMO, and LUMO have major contributions of the N-amido fragment and Ru dxy-t2g orbital; this combination of unoccupied atomic 4d-Ru orbital (d4 configuration in pseudo-octahedral symmetry) and 2p-N orbitals results in three molecular orbitals: a bonding occupied orbital with contribution Ru-N orbitals, a non-bonding occupied with main contribution of 2pN Ru-N and a anti-bonding Ru-N orbital. Whereas HOMO-1, and HOMO-2 have major contributions from nonbonding Ru d-t2g orbitals (dyz, dxz), according to its d4 configuration. For further details of transitions and selected frontier MO see tables S13, S14, S16, and S17. Figure S19 shows molecular orbitals centred at Ru and N-amido group to represent this electronic structure.

Figure 3.

Calculated electronic transitions and UV-Vis spectra for a) RuII-H0 ⇌ RuII-H1 + H+, and b) RuIV-H2 + H+ ⇌ RuIV-H1.

Figure 3 shows calculated transitions and UV-Vis spectra for RuIV-H2 and RuIV-H1, and RuII-H0 and RuII-H1 (eq. 1 and 2, respectively), as well as electron density difference maps (EDDM) for the lowest energy transitions. For the RuII-H0 ⇌ RuII-H1 + H+ equilibria (eq. 1), electronic structure shows a strong destabilization of dπRu by the induction effect of the of anionic ligand over the nitrogen free-electron pair, resulting on a smaller HOMO-LUMO gap of the deprotonated complex. This is reflected in the UV-vis spectrum and calculated transitions showing a MLCT at lower energy (cf. Figure 3a). The MO diagram and percental contribution (Figure S5 and Table S13) were used to assign electronic transitions (Tables S14-15). For RuII-H1, the lowest transition can be assigned as ML-LCT (metal-ligand to ligand charge transfer) due to the significant contribution of the Ru ⚍ N bond in the transition. EDDM plots for the lowest transitions of RuII-H0 and RuII-H1 show that the nitrogen p-orbital has a significant contribution to the lowest energy transitions for RuII-H1, in agreement with the assignments, indicative of increasing Ru-N bond order.

For the RuIV-H2 + H+ ⇌ RuIV-H1 equilibria (eq. 3), the FMO’s show that the HOMO is centred at the N-amido non-bonding, and the LUMO at the Ru ⚍ N π*-bond orbitals in RuIV-H2. Due to the Ru d4 configuration, electronic transitions bring electron density from the equatorial NH nitrogen to the dπ-t2g orbital shifting electron density to the deficient metal. The character of the lower energy transition could be represented as LMCT/MC. Upon protonation at the N-amido in RuIV-H2, the Ru ⚍ N bond is weakened and the contribution of that nitrogen p-orbital to HOMO orbital disappear due to the formation of the N-H bond. This results in a change in character of the lowest transition to LMCT at higher energies (Figure 3b).

With these results we computed the spectra of the intermediates in this system that have not been observed, which will be valuable in future studies of 2e−/2H+ reactions. Using TD-DFT, the MO diagram, percental contribution, and electronic transitions were obtained for all of the possible intermediates. Notably, the calculated UV-vis spectra of intermediates confirm their absence in the studied 2e−/2H+ transfers that form and cleave a variety of O─H, N─H, S─H, and C─H bonds.17 Upon oxidation of RuII-H0 to RuIII-H0, (Figures S10, S11; Tables S19, S20) one dπRu orbital splits becoming part of αHOMO and βLUMO orbitals as this is d5 configuration. This shifts the MLCT transitions to higher energies and mixes them with MC and LMCT transitions. Upon reduction of RuIV-H2 to RuIII-H2, (Figures S13, S14; Tables S21, S22) the LUMO π*Ru ⚍ N orbital splits becoming part of αHOMO and βLUMO orbitals in this d5 complex. The transitions decrease in energy and have ML-LCT contributions. The 1e−/1H+ steps from RuII-H0 to RuIII-H1 to RuIV-H2, cause an even change in transition energies as the total charge remains the same. As oxidation is taking place, stabilization of the rest of d-electrons is observed with the generation Ru ⚍ N orbitals by deprotonation, increasing contribution in electronic transitions from amido group. Figure 4 shows the simulated electronic transitions for RuII-H0, RuIII-H1, and RuIV-H2, with the change in energetics and electronic transition character (details for MO orbital contribution and simulated spectra are in Figures S15-S17, and Tables S23, S24).

Figure 4.

Simulated electronic transitions spectra for each 1e−/1H+ step: RuII-H0 → RuIII-H1 → RuIV-H2.

Computations of thermochemical properties.

Calculated acid-base equilibria pKa’s and redox potentials E° have been used to complement the experimentally accessible data, and to estimate inaccessible data. We also calculated thermochemical parameters for the complex [Ru(acac)2(py-imH)] in order to minimize potential systematic errors of the continuum solvation method and compensate for intrinsic method corrections.25 Comparisons among different functionals and basis sets show a low level of data dispersion, thus supporting the accuracy of the selected level of theory (see SI for further details).

In figure 5a, are presented the experimental results obtained together with the computed pKa and E° values. At the corners for RuIV-H2 and RuII-H0 there is a good agreement with experimental values. Compensation with the parent [Ru(acac)2(py-imH)] was helpful to compensate errors because it has similar volume and coordination scheme, despite that them have different charges, but it is a well characterized complex with all corners of the square measured in MeCN.27 E° values are in the error of ~0.1 V and pKa of ~1 unit. Even the estimated experimental values agree with computations for RuIII-H0 ⇌ RuIII-H1 + H+, and RuIII-H1/RuIV-H1.

Figure 5.

a) Double square scheme for ruthenium amine/amido complex at different redox and protonation states, with experimental and calculated data. b) Simulated Pourbaix diagram with calculated pKa and E°, red lines show the RuII/III couple and blue lines the RuIII/IV couple.

The agreement between calculations and experiments inspired us to calculate thermochemical values for experimentally inaccessible intermediates. This allowed us to complete a double square scheme for this system (Figure 5a) and an extended Pourbaix diagram for the couples RuII/III in red and RuIII/IV in blue, both in MeCN, similar to related computational PCET studies (Figure 5b).25a Our calculations indicate an inversion of the reduction potentials, consistent with the experimental results above. That is, we observe that upon the initial 1e−/1H+ PCET, the subsequent 1e−/1H+ PCET event is thermodynamically more favourable, thus resulting in a net 2e−/2H+ transfer. The other kinetics parameters should be evaluated, as this indicates only the energetic profile.

Combining the pKa and E° values shows that there is a wide region of the Pourbaix diagram that has a 59 mV/pKa slope, for an ne−/nH+ redox couple. This Nernstian behaviour extends over 23-28 pKa units in MeCN. This diagram is similar to the Pourbaix diagram reported for this system in water, except that in that solvent there is a small region of stability for RuIII-H0 below pH 2, and only pH 0-7 could be examined.14 This extended 59 mV/pKa behaviour is observed for metal complexes where the ligand atom is directly protonatable as in M-OH and M-NH bonds.10 As it was mentioned, this situation is common in water oxidation catalysts.28-29

Implications for Reactivity.

The understanding of this system developed above – the structures, electronic structures, and thermochemistry – has implications for the chemical reactivity of the ruthenium complexes. Upon 1e− oxidation of RuII-H0 (E1/2 = 0.26 V), the resulting RuIII-H0 intermediate becomes significantly more acidic (pKa = 6.6 in acetonitrile), as discussed above. Then, successive oxidation to reach RuIV shows redox potential inversion (ΔE1/2 > 0.35 V). Likewise, deprotonation of RuII-H0 (pKa = 33.5) is highly unfavourable. These patterns of large shifts in pKa upon redox change, or large shifts in E1/2 upon proton transfer, are known to favour the transfer of both e− and H+ in a single kinetic step (termed concerted proton-electron transfer, CPET).4 The shifts for the RuIV-H2/RuIII-H1 couple are even larger. Outer-sphere reduction of RuIV-H2 is difficult (E1/2 < −1eV), as is its protonation to yield the RuIV-H1 (pKa = 1.5; is close to that of TfOH).

Both 1e−/1H+ process in the interconversion of the RuIV-H2/RuII-H0 couple are therefore likely to proceed by CPET, which combined result in a total 2e−/2H+ transfer. Also, the potential inversion, that the intermediate RuIII-H1 is unstable to disproportionation, provides a thermodynamic push for both 1e−/1H+ steps to occur simultaneously. The calculations give the N-H BDFEs as 72 kcal/mol for RuII-H0 and 64 kcal/mol for RuIII-H1. The smaller BDFE of RuIII-H1 versus RuII-H0 is the main reason for the RuIII-H1 intermediate not being detected experimentaly.17-18

The origin of the large pKa/E1/2 shifts is the formation of Ruamide π bonds, which progressively stabilize the higher oxidation states and destabilize the d5 configuration. Notably, a similar scenario has been described for a number Ru-O(H)x complexes on the basis of the structural rearrangements, however with a smaller destabilization of the intermediate RuIII(OH) complexes, so that potential inversion is not typically observed in these 2e−/2H+ transfers.29

This ruthenium amide system has been shown to undergo 2e−/2H+ transfers can be readily carried out in aprotic, non-polar solvents, for a diverse set of X─H bonds, in both oxidative and reductive directions.16 This could indicate a small reorganization energy for the 2e−/2H+ RuIV-H2 / RuII-H0 couple. The lack of a net charge change for the 2e−/2H+ PCET interconversion suggests a small outer-sphere reorganization energy. This reactivity should therefore mostly be dominated by the intrinsic barrier by innersphere reorganization energy, especially the formation of the short, strong Ru─amide bonds, and the strong regulation of the 2 H transfer coordinate.

Conclusion

Structural and thermochemical information for bis(amino)ruthenium(II) and bis(amido)ruthenium(IV) complexes is used to further understand their 2e−/2H+ PCET reactivity. Crystal structures, redox potentials and pKa’s of these species in combination with DFT and TD-DFT calculations allowed us to establish the relative stability of intermediates in the overall 2e−/2H+ transfers. The structural changes between RuII-H0 and RuIV-H2 are primarily in the Ru-N-H fragments between amine-amido transitions. Experimental thermochemical data validates calculated values obtained by DFT and combined provide a simulated Pourbaix diagram and double square scheme in MeCN. The combined thermochemical characterization captures the instability for ruthenium(III) species and the potential inversion for these pair of redox couples sustained by the stabilization with the Ru=N bond formation. This provides a thermodynamic preference for coupled 2e−/2H+ transfers, consistent with the previously observed 2e−/2H+ reactivity in non-protic solvents.16 The electronic structure characterization of the complexes and intermediates in 2e−/2H+ transfers provide insight into the metal-ligand cooperativity in their PCET reactivity, and a roadmap to further exploit their 2e−/2H+ reactivity, which studies are currently under development.

Experimental Section

General.

All reagents were purchased as reagent grade and used without further purification. Reagent grade solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific or EMD chemicals. [RuII(bpy)(en*)2](PF6)2 ([RuII-H0](PF6)2) and [RuIV(bpy)(en-H*)2](PF6)2 ([RuIV-H2](PF6)2), were synthesized as was reported.13,16 Crystallizations were made by slow evaporation of acetone in toluene allowing good quality crystals.

Instruments.

Electrochemical measurements were recorded using degassed dry MeCN with Bu4NPF6 used as conducting salt, I= 0.1 M and the complex concentration was ~1mM. A common three electrode setup was used with a glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum wire as a counter electrode, and Ag/AgNO3 as reference electrode. All data were referenced vs the Fc+/0 redox potential. UV-vis spectra were acquired with a Hewlett-Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer in anhydrous MeCN. Acid base titration were measured in MeCN solutions with stoichiometric addition of acid or base. Deprotonation of RuII-H0 was done with DBU (pKaMeCN= 24.34)22 and P2-t-Bu-phosphazene (pKaMeCN=33.5).20 Protonation of RuIV-H2 was done with triflic acid (pKaMeCN= 2.6)23 2,6-dichloro-anilinium BF4 (pKaMeCN= 5.06).22 and 2,6-dimethoxy-pyridine hydrochloride (pKaMeCN= 7.64).21

X-ray Structural Determinations.

Crystals of [RuII-H0](PF6)2 were grown from the slow evaporation of acetone/toluene solutions inside a N2 glove box. Crystals of [RuIV-H2](PF6)2 were grown by slow evaporation of acetone/toluene solutions of the complex under air. The crystals were mounted onto glass capillaries with oil. The data were collected on a Bruker APEX II diffractometer. The data were integrated and scaled using SAINT/SADABS.30 Solution by direct methods (SIR97) produced a complete heavy-atom phasing model consistent with the proposed structure.31 All of the hydrogen atoms were located using a riding model. All of the non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically by full-matrix least-squares (SHELXL).32 Half of a solvent molecule per Ru is found in the unit cells of [RuII-H0](PF6)2 (0.5 C3H6O). In the structure of [RuII-H0](PF6)2, each of the unit cell contains two independent ruthenium complexes with slightly different parameters.

Deposition numbers 2100726 (for RuII-H0), and 2100725 (for RuIV-H2) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Computational Details.

DFT calculations were carried out to characterize the Ruthenium complex in the oxidation states II and IV, and other intermediate species. Optimization, single point energy, frequencies and electronic transitions were carried out using Gaussian 09 software.33 Detailed calculation methods used are available in sup info. GaussSum 3.034 software was used to analyse and plot molecular orbitals, group contributions, electronic transitions and electron density difference maps (EDDM).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

M.C. thanks FONCyT of Argentina (Grant PICT-2016-3224), and UNT (Grant PIUNT 26D/620) for financial support. M.C. is member of the Research Career (CONICET). G.A.P., A.L.T. and J.M.M. acknowledge the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant GM050422), which also supported M.C. during his postdoctoral stay at the University of Washington, when this work was initiated.

References

- [1].a) Hammes-Schiffer S, Acc. Chem. Res, 2018, 51, 1975–1983; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Darcy JW, Koronkiewicz B, Parada GA, Mayer JM, Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 2391–2399; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Warren JJ, Mayer JM, Biochemistry, 2015, 54, 1863–1878; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Tyburski R, Liu T, Glover SD, Hammarström L, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 560–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Nomrowski J, Wenger OS, Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 3680–3687; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huynh MT, Mora SJ, Villalba M, Tejeda-Ferrari ME, Liddell PA, Cherry BR, Teillout A-L, Machan CW, Kubiak CP, Gust D, Moore TA, Hammes-Schiffer S, Moore AL, ACS Cent. Sci 2017, 3, 372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lebedeva NV, Schmidt RD, Concepcion JJ, Brennaman MK, Stanton IN, Therien MJ, Meyer TJ, Forbes MDE, J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 3346–3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Mayer JM, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2004, 55, 363–90; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huynh HV, Meyer TJ, Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 5004–5064; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM, Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 6961–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Tang HR, McKee ML, Stanbury DM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 8967–8973; [Google Scholar]; b) McKee ML, Stanbury DM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 3214–3219; [Google Scholar]; c) Hagenbuch JP, Stampfli B, Vogel P, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 3934–3935; [Google Scholar]; d) Reetz MT, Adv. Organometallic Chem 1977, 16, 33–65; [Google Scholar]; e) Reetz MT, Tetrahedron 1973, 29, 2189–2194; [Google Scholar]; f) Paquette LA, Kesselmayer MA, Rogers RD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 284–291; [Google Scholar]; g) Paquette LA, O'Doherty GA, Rogers RD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 7761–7762. [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Schrauben JN, Cattaneo M, Day TC, Tenderholt AL, Mayer JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 16635–45; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pannwitz A, Prescimone A, Wenger OS, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017, 609–615. [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Houk KN, Li Y, McAllister MA, O’Doherty G, Paquette LA, Siebrand W, Smedarchina ZK, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 10895; [Google Scholar]; b) Mackenzie K, Astin KB, Gravett EC, Gregory RJ, Howard JAK, Wilson C, J. Phys. Org. Chem 1998, 11, 879; [Google Scholar]; c) Tang HR, Stanbury DM, Inorg. Chem 1994, 33, 1388. [Google Scholar]; a) Koper MTM, Chem. Sci 2013, 4, 2710–2723; [Google Scholar]; b) Koper MTM, J. Electroanal. Chem 2011, 660, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Hammes-Schiffer S, Energy Environ. Sci 2012, 5, 7696–7703; [Google Scholar]; b) Hammes-Schiffer S, Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1975–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Nugent WA, Mayer JM in Metal-Ligand Multiple Bonds, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1988; [Google Scholar]; b) Wigley DE, Progress Inorg. Chem 1994, 42, 239; [Google Scholar]; c) Eikey RA, Abu-Omar MM, Coord. Chem. Rev 2003, 243, 83–124; [Google Scholar]; d) Che C-M, Pure&Appl. Chem 1995, 67, 225–232; [Google Scholar]; e) Pietraszuk C, Rogalski S, Powała B, Mietkiewski M, Kubicki M, Spolnik G, Danikiewicz W, Wozniak K, Pazio A, Szadkowska A, Kozłowska A, Grela K, Chem. Eur. J 2012, 18, 6465–6469; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Berry JF, Comm. Inorg. Chem 2009, 30, 28–66. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Slattery SJ, Blaho JK, Lehnes J, Goldsby KA, Coord. Chem. Rev 1998, 174, 391–416. [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Neill J, Nam AS, Barley KM, Meza B, Blauch DN, Inorg. Chem 2008, 47, 5314–5323; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chiu W-H, Cheung K-K, Che C-M, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1995, 441. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Thompson MS, Meyer TJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 5577–5579. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Guan X, Law S-M, Tse C-W, Huang J-S, Che C-M, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 15122–15130; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Burrell AK, Steedman AJ, Organometallics 1997, 16, 1203–1208; [Google Scholar]; c) Yi X-Y, Ng H-Y, Williams ID, Leung W-H, Inorg. Chem 2011, 50, 1161–1163; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ishizuka T, Kogawa T, Makino M, Shiota Y, Ohara K, Kotani H, Nozawa S, Adachi S, Yamaguchi K, Yoshizawa K, Kojima T, Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 12815–12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chiu W-H, Peng S-M, Che C-M, Inorg. Chem 1996, 35, 3369–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Keene FR, Coord. Chem. Rev 1999, 187, 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kagalwala HN, Deshmukh MS, Ramasamy E, Nair N, Zhou R, Zong R, McCormik L, Chem P-A, Thummel RA, Inorg. Chem 2021, 60, 1806–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cattaneo M, Ryken SA, Mayer JM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 3675–3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Perez EH, Menges FS, Cattaneo M, Mayer JM, Johnson MA, J. Chem. Phys 2020, 152, 234309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vigara L, Ertem MZ, Planas N, Bozoglian F, Leidel N, Dau H, Haumann M, Gagliardi L, Cramer CJ, Llobet A, Chem. Sci 2012, 3, 2576. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kütt A, Selberg S, Kaljurand I, Tshepelevitsh S, Heering A, Darnell A, Kaupmees K, Piirsalu M, Leito I, Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 3738–3748. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Curtis JC, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ, Inorg. Chem 1983, 22, 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ishikawa T in Superbases for Organic Synthesis, Wiley & Sons, 2009, p-147. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kaljurand I, Kutt A, Soovali L, Rodima T, Maemets V, Leito I, Koppel IA, J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tshepelevitsh S, Kütt A, Lõkov M, Kaljurand I, Saame J, Heering A, Plieger PG, Vianello R, Leito I, Eur. J Org. Chem 2019, 6735–6748. [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Solis BH, Hammes-Schiffer S, Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 6427–6443; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Emelyanova N, Sanina N, Krivenko A, Manzhos R, Bozhenko K, Aldoshin S, Theo. Chem. Acc 2013, 132, 1316; [Google Scholar]; c) Salomón FF, Vega NC, Parella T, Morán Vieyra FE, Borsarelli CD, Longo C, Cattaneo M, Katz NE, ACS Omega 2020, 5, 8097–8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Details of calculations methods followed for E0 and pKa are in supp info.

- [27].Wu A, Masland J, Swartz RD, Kaminsky W, Mayer JM, Inorg. Chem 2007, 46, 11190–11201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Matheu R, Garrido-Barros P, Gil-Sepulcre M, Ertem MZ, Sala X, Gimbert-Suriñach C, Llobet A, Nat. Rev. Chem 2019, 3, 331–341; [Google Scholar]; b) Llobet A in Molecular Water Oxidation Catalysis: A Key Topic for New Sustainable Energy Conversion Schemes, Wiley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Roglans A, Parella T, Benet-Buchholz J, Poyatos M, Llobet A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 5306–5307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bruker (2007) APEX2 (Version 2.1-4), SAINT (version 7.34A), SADABS (version 2007/4), BrukerAXS Inc, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. [Google Scholar]

- [31].(a) Altomare A, Burla C, Camalli M, Cascarano L, Giacovazzo C, Guagliardi A, Moliterni AGG, Polidori G, Spagna R, J. Appl. Cryst 1999, 32, 115; [Google Scholar]; (b) Altomare A, Cascarano G, Giacovazzo C, Guagliardi A, J. Appl. Cryst 1993, 26, 343. [Google Scholar]

- [32].a) Sheldrick GM, Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem 2015, 71, 3; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mackay S, Edwards C, Henderson A, Gilmore C, Stewart N, Shankland K, Donald A. maXus 1.1, A computer program for the solution and refinement of crystal structures from X-ray diffraction data, University of Glasgow, Scotland, Nonius, The Netherlands, and MacScience, Japan: (1997). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gaussian 09, Revision A.02, Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Li X, Caricato M, Marenich A, Bloino J, Janesko BG, Gomperts R, Mennucci B, Hratchian HP, Ortiz JV, Izmaylov AF, Sonnenberg JL, Williams-Young D, Ding F, Lipparini F, Egidi F, Goings J, Peng B, Petrone A, Henderson T, Ranasinghe D, Zakrzewski VG, Gao J, Rega N, Zheng G, Liang W, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Throssell K, Montgomery JA Jr., Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith T, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Millam JM, Klene M, Adamo C, Cammi R, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Fox DJ, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [34].O'Boyle NM, Tenderholt AL, Langner KM. J. Comp. Chem 2008, 29, 839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.