Abstract

Emerging evidence indicates that for some people, the COVID-19 lockdowns are a time of high risk for increased food intake. A clearer understanding of which individuals are most at risk of over-eating during the lockdown period is needed to inform interventions that promote healthy diets and prevent weight gain during lockdowns. An online survey collected during the COVID-19 lockdown (total n = 875; analysed n = 588; 33.4 ± 12.6 years; 82% UK-based; mostly white, educated, and not home schooling) investigated reported changes to the amount consumed and changes to intake of high energy dense (HED) sweet and savoury foods. The study also assessed which eating behaviour traits predicted a reported increase of HED sweet and savoury foods and tested whether coping responses moderated this relationship. Results showed that 48% of participants reported increased food intake in response to the COVID-19 lockdown. There was large individual variability in reported changes and lower craving control was the strongest predictor of increased HED sweet and savoury food intake. Low cognitive restraint also predicted greater increases in HED sweet snacks and HED savoury meal foods. Food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, emotional undereating, emotional overeating and satiety responsiveness were not significant predictors of changes to HED sweet and savoury food intake. High scores on acceptance coping responses attenuated the conditional effects of craving control on HED sweet snack intake. Consistent with previous findings, the current research suggests that low craving control is a risk factor for increased snack food intake during lockdown and may therefore represent a target for intervention.

Keywords: COVID-19 lockdown, Food intake, Eating behaviour traits, Craving control, Cognitive restraint, Acceptance coping responses

1. Introduction

To control the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), Governments across the world enforced orders for people to stay at home and engage in social distancing (e.g. UK Government, 2020). While such lockdowns are important to limit viral transmission, they risk undermining engagement in health behaviours such as adopting a balanced and nutritious diet. Early survey findings from participants based mostly in Africa and Asia, reported increased snacking in response to COVID-19 lockdowns (Ammar et al., 2020). Such dietary changes have important public health implications as repeated episodes of overconsumption, even by 10–50 calories a day promote weight gain and increase risk of obesity (Hall et al., 2011). Considering that obesity is a current major public health priority in Western countries (World Health Organization, 2020b), it is important to understand the impact that COVID-19 has on diet and identify which individuals are most susceptible to increasing food intake during this high-risk time.

There are multiple aspects of the COVID-19 lockdowns that are associated with greater risk of increased food intake. Lockdown orders to stay at home, concern over viral contraction and financial uncertainty all negatively impact psychological wellbeing by increasing stress, boredom, loneliness and other negative emotions (Brooks et al., 2020; Daly, Sutin, & Robinson, 2020; Shevlin et al., 2020). Psychological distress has been linked with greater food intake, especially increased intake of high fat, energy dense and palatable snack foods (Abramson & Stinson, 1977; Adam & Epel, 2007; Epel, Lapidus, McEwen, & Brownell, 2001; Hill, Weaver, & Blundell, 1991; Oliver & Wardle, 1999; Wardle, Steptoe, Oliver, & Lipsey, 2000). Indeed, recent findings from a survey in French adults, reported that 37–43% of respondents indicated eating to reduce stress, boredom and feelings of emptiness experienced during the COVID-19 lockdown (Cherikh et al., 2020).

Additionally, food-rich environments, where food is easily available, is a main driver of overconsumption (Lowe & Butryn, 2007; Swinburn et al., 2011). In response to the COVID-19 lockdown there has been increased stockpiling of foods (Nicola et al., 2020), meaning that homes, where people are restricted to stay for most of the day are potentially food-rich environments that promote overconsumption. As such, the COVID-19 lockdowns are a time of high risk for increased food intake and ultimately weight gain in susceptible individuals.

Early evidence from multiple countries across the world have reported dietary changes in response to the COVID-19 lockdowns (Allabadi, Dabis, Aghabekian, Khader, & Khammash, 2020; Ammar et al., 2020; Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020; Matsungo & Chopera, 2020; Mitchell, Yang, Behr, Deluca, & Schaffer, 2020; Robinson, Gillespie, & Jones, 2020; Sidor & Rzymski, 2020). Importantly, in most studies not all participants report increased food intake in response to the COVID-19 lockdowns. Rather, studies have identified subgroups of individuals who report increased intake, subgroups who report no changes and subgroups who report decreased food intake (Allabadi et al., 2020; Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020). This individual variability in response to COVID-19 reflects the individual variability found in response to the obesogenic environment, with some individuals being more susceptible to increased food intake than others (Blundell et al., 2005; Finlayson, Cecil, Higgs, Hill, & Hetherington, 2012). The Behavioural Susceptibility Theory (Llewellyn & Wardle, 2015) explains individual variability in food intake by proposing that genetic predispositions determine appetitive traits which interact with the environment. Individuals scoring high in appetite traits such as food responsiveness and enjoyment of food will increase food intake in food-rich environments that permit these traits to manifest. The theory suggests that increased food intake is more likely to occur for foods that are commonly reported to be difficult to control or difficult to resist intake of, such as high energy dense (HED) sweet and savoury foods (Christensen, 2007; Hill & Heatonbrown, 1994; Roe & Rolls, 2020). Applied to the COVID-19 lockdown, this suggests that individuals scoring high in appetitive eating behaviour traits linked with susceptibility to increased food intake will report increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods.

It is currently unclear which eating behaviour traits predict susceptibility to increased food intake in response to COVID-19 lockdowns. Identifying these traits is particularly important because studies have found that participants who report increased food intake are at greater risk of weight gain than participants reporting no changes or reduced food intake in response to COVID-19 lockdowns (Allabadi et al., 2020; Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020). Identifying the characteristics of individuals who report increased food intake will be important for informing strategies to prevent excessive food intake and risk of weight gain and obesity in future viral outbreaks (Xu & Li, 2020).

Given that the COVID-19 lockdown is linked with increased psychological distress (Daly et al., 2020; Shevlin et al., 2020), the way in which people respond and cope with the pandemic may also affect dietary responses to the COVID-19 lockdown. Coping styles refer to the way in which people respond to and manage stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Adopting maladaptive coping strategies such as self-blame, behavioural disengagement and venting are linked with negative affect and impaired well-being (Kato, 2015). Use of maladaptive coping strategies prolong psychological distress and this prolonged distress has been hypothesised to lead to stress-induced eating (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). In contrast, adopting adaptive strategies such as active coping, positive reframing and acceptance have been found to reduce psychological distress (Aldao et al., 2010; Kato, 2015). Active coping refers to active attempts to improve a situation, positive reframing refers to adopting a positive perspective to challenging situation and acceptance refers to accepting reality and accepting the uncomfortable cognitions and feelings in a non-judgemental way (Carver, 1997). Of these three strategies linked with reduced distress, acceptance has been the coping strategy most applied to eating behaviours. Studies have reported that accepting challenging cognitions such as cravings, reduces food cravings, food intake (Alberts, Mulkens, Smeets, & Thewissen, 2010; Alberts, Thewissen, & Middelweerd, 2013; Forman et al., 2007) and supports weight loss in people with disinhibited eating styles (Schumacher, Kemps, & Tiggemann, 2017). In relation to COVID-19, people who adopt adaptive coping strategies (acceptance, active coping and positive reframing) may be less likely to report increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods. Identifying effective strategies that reduce the negative impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on food intake is important to inform future lockdown-based interventions that promote controlled food intake and prevent weight gain. To date, no research has examined whether adopting adaptive coping strategies buffer against increased food intake during the COVID-19 lockdown.

The aims of this study were threefold; firstly to assess reported changes in food intake (overall amounts consumed and for HED sweet and savoury foods) during the COVID-19 lockdown. Secondly, to identify eating behaviour traits that predict increased susceptibility to increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods. Thirdly, the study explored whether adopting coping strategies previously linked with reduced distress (active coping, acceptance and positive reframing) moderate the relationship between eating behaviour traits and changes to HED sweet and savoury foods (not pre-registered).

As specified in the preregistered protocol (https://osf.io/b8atr/), it was hypothesised that most participants would report increases in the amount of food consumed and increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods during the COVID-19 lockdown (Ammar et al., 2020). Higher scores on food responsiveness, enjoyment of foods, emotional overeating and low craving control were expected to be associated with increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods. Whereas, higher scores on emotional undereating, satiety responsiveness and cognitive restraint were expected to be associated with lower reports of increased intake (preregistered). Finally (not pre-registered), it was expected that high scores on adaptive coping strategies (active coping, acceptance and positive reframing coping) would attenuate the relationship between eating behaviour traits linked with increased susceptibility and increased intake.

2. Methods

The study protocol was pre-registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/b8atr/). The protocol refers to the primary research questions addressed here (overall dietary changes and eating behaviour traits) as well as secondary mediation and moderation analyses not reported here but planned for secondary analyses.

3. Participants

To achieve adequate power for testing a small effect size, we aimed to recruit at least 500 participants aged ≥18 years. We followed sample size recommendations outlined by Fritz and MacKinnon (2007) and took a conservative approach to ensure that the sample size provided enough power for the current analysis and for potential further analyses [i.e., secondary mediation data analyses (0.8 power, small effect size mediation analyses using bias-corrected bootstrapping)].

Recruitment strategies were primarily UK based (included social media, email distribution lists, survey recruitment website ‘Call for Participants’, online forums and online panel provider Prolific) but participants from non-UK countries were eligible to participate. In total, responses were collected from 875 participants between 15th May and June 27, 2020. Of these, 143 dropped out before completing any survey questions, twenty-six were excluded from survey participation for having an eating disorder and two participants were excluded for incorrectly answering both attention check questions. Of the remaining participants, 485 were from the UK and 219 from non-UK countries. As lockdown situations differed across countries, for non-UK respondents only respondents who indicated that they were in lockdown, self-isolating, only going out for essential reasons and staying at home as much as possible were included (n = 103). Non-UK respondents who indicated that they were no longer under lockdown conditions (n = 89) or did not specify lockdown conditions were excluded (n = 27). As such, the final eligible sample comprised of 588 participants. Of the 588 participants, 499 participants completed the survey (85% completion rate). However, participants were retained in the analysis up to the point at which they dropped out; therefore sample sizes vary for each variable reported. Whilst this final completed sample size fell short of the planned sample size, Ellis (2010) suggests that this sample size is sufficient to detect a small effect size correlation coefficient (r = 0.15). Of note, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers for any sample characteristic variables measured (smallest p = .18; means not reported here).

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Reported changes to food intake

Overall changes to the amount of food consumed, snack intake, meal intake and craving frequency and intensity were assessed using single item questions generated by the research team [amount: “Has the AMOUNT of food you have eaten changed since the lockdown?“; snack intake: “Has the AMOUNT of SNACK FOODS that you have eaten changed since the lockdown?“; meal intake: “Has the AMOUNT YOU HAVE EATEN AT MEALS (e.g. breakfast, lunch, dinner) changed since the lockdown?“; craving frequency: “Have the AMOUNT of FOOD CRAVINGS (A food craving is a strong urge to eat a particular food or drink)” you've experienced changed since the lockdown); craving intensity: “Have the STRENGTH of the FOOD CRAVINGS you've experienced changed since the lockdown?“].

To assess changes to HED sweet and savoury foods, participants reported changes to individual food items that have previously been reported to be difficult to control intake of (Christensen, 2007; Hill & Heatonbrown, 1994; Roe & Rolls, 2020). Scores for individual food items were averaged for HED sweet snacks, HED savoury snacks and HED savoury meals. HED sweet snacks comprised chocolate, biscuits, cakes, other sweet baked foods, sweets and ice cream (Cronbach's α = 0.81). HED savoury snack foods comprised crisps or other packet savoury snacks, peanuts or other nuts, cream crackers, cheese biscuits and cheese (Cronbach's α = 0.57). HED savoury meal foods comprised of pizza, white pasta, chips or French fries, white bread and rolls and savoury pies (Cronbach's α = 0.73). The survey also assessed reported changes to fruit and vegetables. In the pre-registration protocol (https://osf.io/b8atr/) it was initially planned to average responses to fruit and dried fruit, however due to low internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.23) only responses to the food item fruit were assessed.

Responses to questions assessing changes to food intake were collected on a scale range from ‘0 = I eat a lot less’; ‘50 = no change’; and ‘100 = I eat a lot more’ (anchors adapted for each question). For all questions the cursor was set at the mid-point, and participants were required to select and position the cursor on the scale at the point which best represented their response to the question. This scale was converted to a ‘-50 = eat a lot less’ to ‘50 = eat a lot more’ with ‘0 = no change’ scale by deducting 50 from the obtained raw scores. As such, negative scores indicate reduced intake and positive scores indicate increased intake. As well as assessing this variable as a continuous variable, scores were categorised to allow for frequencies to be reported. Scores ≤ -6 were classified as decreased intake, scores ranging between −5 and +5 were classified as no change (this range was chosen for ‘no change’ rather than using values of zero only to allow for some response error recording no change responses) and scores ≥ 6 were classified as increased intake.

3.1.2. Habitual food intake before the lockdown

To control for habitual diets prior to the lockdown, participants completed an adapted version of the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (Mulligan et al., 2014). Only food items related to HED sweet and savoury foods and fruits and vegetables were included. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency to which they consumed a medium serving of each food item before the COVID-19 lockdown. Scores ranged from ‘0 = never or less than once a month’ to ‘8 = 6+ times a day.’ Individual food items were averaged to produce scores for the following food groups: HED sweet snacks (Cronbach's α = 0.70), HED savoury snacks (Cronbach's α = 0.39) and HED savoury meal foods (Cronbach's α = 0.64).

3.1.3. Eating behaviour traits

The Adult Eating Behaviour questionnaire (AEBQ) (Hunot et al., 2016) was used to assess appetitive traits linked with susceptibility to increased food intake. In the current study the following subscales were administered: food responsiveness (Cronbach's α = 0.71), enjoyment of food (Cronbach's α = 0.83), emotional overeating (Cronbach's α = 0.85), emotional undereating (Cronbach's α = 0.86), and satiety responsiveness (Cronbach's α = 0.74). Responses were collected on a 5-point scale (’1 = strongly disagree’ and ‘5 = strongly agree’). The AEBQ is a valid measure to assess individual differences in food approach and food avoidance (Hunot et al., 2016; Mallan et al., 2017).

Cognitive restraint was assessed with the 6-item cognitive restraint subscale of the revised Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) (Cronbach's α = 0.78) (Karlsson, Persson, Sjostrom, & Sullivan, 2000). Cognitive restraint assesses individual differences in volitional efforts to control food intake as a means to manage body weight. Higher cognitive restraint is associated with lower energy intake (Bryant, Rehman, Pepper, & Walters, 2019). Responses were collected on a 4-point scale.

The Control of Eating Questionnaire (CoEQ) (Dalton, Finlayson, Hill, & Blundell, 2015) assesses the severity and type of food cravings experienced over the previous 7 days. Items on the CoEQ were assessed by 100-point visual analogue scale, with items averaged to create a final score. The 5-item Craving Control subscale was used in the current study (Cronbach's α = 0.90). Research has shown the CoEQ to have very good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha 0.92) and validity (Dalton et al., 2015, 2017).

3.1.4. Coping strategies

Coping strategies were assessed using the Brief Cope Questionnaire (Carver, 1997) which is the most commonly used coping scale (Kato et al., 2015). Responses were collected on a 4-point scale (’1 = I have not been doing this at all’ to ‘4 = I have been doing this a lot’). The scale has been found to be reliable and valid (Litman, 2006). For this study, active coping, acceptance and positive reframing were assessed because these three coping strategies have been linked with reduced distress (Kato et al., 2015).

3.1.5. COVID-19 status and lockdown situation

Participants completed a series of questions assessing whether they had contracted COVID-19 (yes, confirmed by test, yes self-diagnosed, possibly, no confirmed by test and I don't think so), the impact of COVID-19 on employment, lockdown status (self-isolating, leave the house only for essentials or work, minimal restrictions - free to attend social gatherings, visit family and friends and access non-essential services), and indicated who they were in lockdown with. Participants also indicated the number of children (if any) that they were home schooling.

3.2. Socioeconomic status (SES)

To characterise the sample based on SES, participants were requested to provide their postcode to determine Index of Multiple Deprivation (Scottish Government, 2020; StatsWales, 2019; UK Government, 2019). The IMD ranks small geographical areas in England, Wales and Scotland. Deciles are reported and range from ‘1 = most deprived’ to ‘10 = least deprived’. Participants also completed the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status subjective social status (Adler & Stewart, 2007). Subjective social status assesses participants' perceived social rank compared to others in society based on money, education and jobs.

3.3. Procedure

The survey was administered online via Qualtrics (Provo, UT). Participants were informed that the survey aim was to investigate eating habits during the COVID-19 lockdown. The survey involved participants completing measures related to eating behaviours and coping responses, as well as additional measures not reported here (questions related to sleep, mental well-being, boredom which are planned for future reports). After providing informed consent, participants completed initial questions on demographics (age, gender, country of residence, postcode, nationality, ethnicity and education), indicated existing health conditions, dieting status and indicated whether they had a history or current eating disorder. Participants then completed questions assessing changes to eating behaviours, followed by indicating habitual intake prior to COVID-19. Next, participants completed the AEBQ (Hunot et al., 2016), the cognitive restraint subscale (Karlsson et al., 2000) and the COEQ (Dalton et al., 2015). Participants then completed the Brief Cope Questionnaire which was presented in a random order with other questionnaires not reported here (measuring sleep, well-being and boredom as reported in the registered protocol). Participants then completed further questions assessing disabilities (Washington Group Short Set of Disabilities Questions, Madans, Loeb, & Altman, 2011), self-reported weight (kilograms or stones and pounds), height [centimetres or feet and inches; body mass index was computed based on self-reported height and weight. Values deemed implausible or at high risk of error were removed (BMI <17 kg/m2 and >60 kg/m2)], reported weight status (ranging from underweight to obese), indicated subjective social status, COVID-19 status and impact and household income prior to COVID-19. Participants were then debriefed and indicated if they wished to be entered into the prize draw to win either a £50 or £100 Amazon voucher, or if recruited via Prolific received a small monetary remuneration. Of note, during the survey for quality control, two attention check questions were included (e.g. ‘What is 2 + 2?‘) and participants who incorrectly answered both questions were excluded. The study was approved by the University of Sheffield's ethics committee. Mean completed survey duration was 25.3 ± 13.4 (24.1, 26.5) minutes.

4. Strategy for data analysis

Data are displayed as means ± standard deviations (95% confidence intervals) unless specified. A series of independent t-tests and chi-squared tests were used to compare completers and non-completers on sample characteristics. Correlations between changes to food intake were initially explored using bivariate correlations (Pearson's r). Due to the number of associations examined, alpha for bivariate correlations was set at p < .01. Pearson's r correlation coefficients were interpreted as .1 small, 0.3 medium and 0.5 large (Cohen, 1992).

To compare reported changes for different food groups, paired-samples t-tests and repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted with Bonferonni corrections applied. To test the linear association between eating behaviour traits, and changes to HED sweet and savoury foods separate linear regression models were computed. All models were adjusted for gender (male, female; the sample size for other gender responses was too low to include in the analysis), country (UK, non-UK) and habitual food intake (FFQ) (step 1, stepwise method), before all eating behaviour traits were entered into the model using the stepwise method. To check for the presence of statistical outliers that might unduly influence the relationship between variables, the residual statistics were examined. A standardised residual of less than −3 or greater than +3 SD was used to indicate that an observation was a statistical outlier. Furthermore, Cook's Distance scores were also calculated, with a score of greater than 1 taken to indicate that an observation unduly influenced the model. To check for multicollinearity between predictor variables, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance statistics were assessed. In all models there were no issues with multicollinearity as based on the VIF (<10), and tolerance values (>0.2; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

To investigate whether the relationship between eating behaviour traits and changes to food intake were moderated by coping strategies moderator analysis was conducted using PROCESS for SPSS (Model 1)(Hayes, 2017). Each model controlled for gender and habitual food intake. Significant interactions were explored with simple slopes at the 16th, 50th and 85th percentiles. The moderation analysis reported here was exploratory based on the eating behaviour traits identified to predict increased food intake. For t-test, F-tests and regression analyses, alpha was set at p < .05.

5. Results

5.1. Participants

The final sample comprised of 588 participants who were mostly females (69%, n = 403; 30% males, n = 176; 1% non-conforming, n = 5; 0.5% other, n = 3 and; 0.2% prefer not to say, n = 1) with a mean age of 33.4 ± 12.6 (32.3, 34.4) years and a mean BMI of 25.1 ± 5.6 (24.6, 25.7) kg/m2 (based on self-reported height and weight). Ethnicity was as follows: 86% (n = 491) White, 7% (n = 42) Asian or Asian British, 3% (n = 20) mixed or multiple ethnic groups, 1% (n = 4) Black, African, Caribbean, or Black British, 1% (n = 5) prefer not to say and 2% (n = 10) other. All other measured participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1 . Of note, most participants classified themselves as having a healthy weight and 39% classified themselves with overweight or obesity which is lower than national prevalence of overweight and obesity (NHS Digital, 2020). Most of the sample were educated and reported having an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. The majority of the sample were living with others during the lockdown and most reported that they were not home schooling.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Variable (total n) | n (%) or M ± SD (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Country of residence (n = 588) | |

| UK | |

| England | 422 (72%) |

| Wales | 32 (5%) |

| Scotland | 11 (2%) |

| Northern Ireland | 3 (1%) |

| Not reported | 17 (3%) |

| Non-UK (n = 103) | 62 (11%) |

| Europe (non-UK country) | 33 (6%) |

| North America | 2 (0.3%) |

| Australasia | 3 (0.5%) |

| Asia | 1 (0.2%) |

| Africa | 1 (0.2%) |

| South America | 1 (0.2%) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.2%) |

| Weight status (n = 500) | |

| Underweight | 20 (4%) |

| Healthy weight | 283 (57%) |

| Overweight | 157 (31%) |

| Obese | 40 (8%) |

| Disability status (n = 501)a | |

| With a disability | 57 (11%) |

| Not with a disability | 444 (89%) |

| Health (n = 572, note some participants selected multiple answer) | |

| No health issues | 353 (62%) |

| Pregnant | 6 (1%) |

| Lactating | 11 (2%) |

| Dieting to lose weight or avoid weight gain | 101 (18%) |

| Weight loss surgery | 0 (0%) |

| Regular smoker | 48 (8%) |

| Diabetic | 7 (1%) |

| Heart disease | 3 (1%) |

| Underactive or overactive thyroid | 18 (3%) |

| Other health condition | 66 (12%) |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation decile (n = 374)b | 6.2 ± 2.87 (5.9, 6.5) |

| Subjective social status (n = 496) | 6.0 ± 1.7 (5.9, 6.2) |

| Household income (n = 499) | |

| < £10 000 | 41 (8%) |

| £10 000 - £20 000 | 76 (15%) |

| £20 000 - £30 000 | 51 (10%) |

| £30 000 - £40 000 | 62 (12%) |

| £40 000 - £50 000 | 54 (11%) |

| £50 000 - £60 000 | 43 (9%) |

| Above £60 000 | 97 (19%) |

| Prefer not to say | 75 (15%) |

| Education (n = 572) | |

| None | 12 (2%) |

| GCSEs > 1 and < 4 | 14 (2%) |

| GCSEs ≥ 5 | 22 (4%) |

| A-levels (≥2) | 110 (19%) |

| Undergraduate degree or equivalent | 256 (45%) |

| Postgraduate degree | 129 (23%) |

| Apprenticeship | 7 (1%) |

| Other | 17 (3%) |

| Prefer not to say | 5 (1%) |

| COVID-19 status (n = 499) | |

| Contracted, confirmed by test | 0 (0%) |

| Contracted, self-diagnosis | 10 (2%) |

| Possibly contracted | 89 (18%) |

| Not contracted, confirmed by test | 15 (3%) |

| Don't think so | 385 (77%) |

| Home schooling (n = 500) | |

| Not home schooling | 407 (81%) |

| 1 child | 34 (7%) |

| 2 children | 44 (9%) |

| 3 children | 13 (3%) |

| 4 + children | 2 (0.4%) |

| COVID-19 employment impact (n = 490) | |

| Key worker | 50 (10%) |

| Working from home | 229 (47%) |

| Unable to work and furloughed or paid | 54 (11%) |

| Unable to work and not furloughed | 24 (4.9) |

| Returned to work after May 13, 2020 | 2 (0.4%) |

| Work availability decreased | 5 (1.0%) |

| Alternative work/new job | 2 (0.4%) |

| Not applicable | 108 (22%) |

| Off sick | 1 (0.2%) |

| Prefer not to say | 11 (2.2%) |

| Other | 3 (1%) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.2%) |

| Living situation (n = 499) | |

| Living alone | 58 (12%) |

| Living with others | 441 (88%) |

| Eating behaviour traits | |

| Food responsiveness (AEBQ) (n = 514) | 3.3 ± 0.8 (3.2, 3.3) |

| Enjoyment of food (AEBQ) (n = 512) | 4.2 ± 0.7 (4.1, 4.2) |

| Emotional overeating (AEBQ) (n = 514) | 2.8 ± 1.0 (2.7, 2.9) |

| Emotional undereating (AEBQ) (n = 512) | 2.9 ± 0.9 (2.8, 3.0) |

| Satiety responsiveness (AEBQ) (n = 512) | 2.5 ± 0.8 (2.4, 2.5) |

| Cognitive restraint (TFEQ) (n = 508) | 13.6 ± 3.6 (13.3, 14.0) |

| Craving control (COEQ) (n = 508) | 52.9 ± 22.9 (50.9, 54.9) |

AEBQ = Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (Hunot et al., 2016); COEQ = Control of Eating Questionnaire (Dalton et al., 2015); TFEQ = Three Factor Eating Questionnaire, revised version (Karlsson et al., 2000).

Note.

Disability status was determined by the Washington Group Short Set of Disability Questions (Madans et al., 2011).

n = 374 due to missing data whereby participants did not provide a valid postcode or were from a non-UK country.

In terms of the lockdown, most participants indicated being under lockdown conditions by only going outside for essential purposes [medical, purchasing essential items, exercise or work (if key worker)] (86%, n = 429) or self-isolating (6%, n = 28). A further 8% (n = 38) indicated that they were free to leave the house and see others from different households whenever they liked and 1% (n = 4) indicated ‘other’ and detailed that they went outside to meet with one other person at a social distance.

5.2. Correlations between reported changes to food intake and eating behaviour traits

Table 2 shows correlations between reported changes in food intake and eating behaviour traits. As expected, higher increased intake (amount overall) was significantly associated with greater HED sweet and savoury food intake, greater craving frequency and intensity (all medium effects), greater food responsiveness (small to medium), greater emotional overeating (small to medium), lower emotional undereating (small effect) and lower craving control (medium effect). Greater reported overall intake was also significantly associated with higher BMI scores, but the association was small (r = 0.14, p = .002).

Table 2.

Correlations between eating behaviour traits and changes to HED sweet and savoury foods.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overall amount | – | ||||||||||||||

| 2. SW snacks | .47*** | – | |||||||||||||

| 3. SAV snacks | .37*** | .60*** | – | ||||||||||||

| 4. SAV meals | .37*** | .63*** | .61** | – | |||||||||||

| 5. Fruit | .02 | -.10 | -.04 | -.10 | – | ||||||||||

| 6. Vegetables | -.04 | -.19*** | -.10 | -.13** | .46*** | – | |||||||||

| 7. Craving freq. | .46*** | .38*** | .31*** | .35*** | -.07 | -.12** | – | ||||||||

| 8. Craving int. | .42*** | .38*** | .36*** | .35*** | -.07 | -.11 | .82*** | – | |||||||

| 9. AEBQ FR | .24*** | .13** | .13** | .11 | .07 | .10 | .15** | .14** | – | ||||||

| 10. AEBQ EF | .04 | .08 | .10 | .05 | .08 | .11 | -.04 | -.02 | .47*** | – | |||||

| 11. AEBQ EOE | .25*** | .13** | .10 | .12** | -.03 | .00 | .24*** | .21*** | .43*** | .15** | – | ||||

| 12. AEBQ EUE | -.19*** | -.13** | -.08 | -.11 | -.00 | .00 | -.20*** | -.18*** | -.14** | -.06 | -.53*** | – | |||

| 13. AEBQ SR | -.10 | -.02 | -.06 | -.00 | .04 | -.04 | .03 | .04 | -.32*** | -.30*** | -.23*** | .25*** | – | ||

| 14. CR | -.03 | -.05 | .03 | -.06 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .04 | .08 | -.01 | .18*** | -.09 | .04 | – | |

| 15. COEQ | -.38*** | -.30*** | -.25*** | -.27*** | .09 | .09 | -.53*** | -.50*** | -.43*** | -.14** | -.44*** | .21*** | .10 | -.11 | – |

Note.

AEBQ = Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire; FR = Food Responsiveness; EF = Enjoyment of Food; EF = Enjoyment of Food; EOE = Emotional Overeating; EOE = Emotional Undereating; SR = Satiety Responsiveness (Hunot et al., 2016).

COEQ = Control of Eating Questionnaire (Dalton et al., 2015).

CR = Cognitive restraint (Karlsson et al., 2000).

Craving freq. = craving frequency.

Craving int. = craving intensity.

HED = high energy dense.

SAV snacks = HED savoury snacks.

SAV meals = HED savoury meals.

SW snacks = HED sweet snacks.

Sample size range = 508–559.

**p < .01.

***p < .001.

Overall changes in the amount eaten did not significantly correlate with changes to fruit and vegetable intake, enjoyment of food, satiety responsiveness or cognitive restraint. Greater reported increases in HED sweet snack intake were significantly associated with increased intake of HED savoury snacks and meal foods, and greater craving frequency and intensity (medium effects). Greater increases in HED sweet snacks and HED savoury meal foods (not HED savoury snacks) were significantly associated with lower vegetable intake, but these association were small. Changes in HED sweet and HED savoury food intake were not significantly associated with changes to fruit intake. The associations between different food groups (HED sweet and savoury foods, fruits and vegetables) indicate that the measures used in the survey had reasonable convergent and divergent validity (Robinson, 2018). For eating behaviour traits, higher scores on food responsiveness and emotional overeating and lower scores on emotional undereating were significantly associated with greater increases in HED sweet and savoury foods (associations between emotional overeating, emotional undereating were not significant for HED savoury meal foods), but the associations were small. Lower craving control was significantly associated with increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods (medium effects), but as expected, craving control was not significantly associated with changes to fruit and vegetable intake. Changes to food groups were not significantly associated with self-reported BMI (largest r = 0.06, p = .21).

5.3. Reported changes to food intake

Table 3 shows reported changes to food intake (overall changes and for HED sweet and savoury foods, fruits and vegetables) in response to the COVID-19 lockdown. Almost half of participants reported increasing the amount of food consumed during the lockdown, with the remaining participants reporting either no changes or reduced intake. Participants were more likely to report increased intake of snacks than increased meal intake [based on percentages, and demonstrated by significantly higher mean snack change scores compared to meals, t(558) = 5.24, p < .001]. Similarly, examination of the percentages showed that fewer participants reported no changes to snack intake than no changes to meal intake. Craving scores indicated that almost a half of participants reported increases in cravings.

Table 3.

Mean ± SD (95% confidence intervals) reported changes to food intake in response to the COVID-19 lockdown.

| Variable | n | M ± SD (95% CI) | Individual response % (n) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased | No change | Increased | |||

| Overall changes | |||||

| Overall amount changed | 559 | 4.5 ± 17.9 (3.1, 6.0) | 27% (150) | 25% (141) | 48% (268) |

| Snack amount changed | 559 | 6.0 ± 21.7 (4.2, 7.8) | 26% (147) | 20% (114) | 53% (298) |

| Meal amount changed | 559 | 1.2 ± 15.7 (−0.2, 2.5) | 23% (131) | 46% (255) | 31% (173) |

| Food cravings changed | 559 | 5.9 ± 20.5 (4.2, 7.6) | 23% (129) | 31% (175) | 46% (255) |

| Food craving intensity changed | 559 | 2.8 ± 18.4 (1.3, 4.3) | 23% (129) | 41% (230) | 36% (200) |

| Specific food types | |||||

| Sweet snacks foods changeda | 549 | −1.6 ± 15.0 (−2.9, −0.3) | 26% (145) | 46% (251) | 28% (153) |

| Savoury snacks foods changeda | 549 | 0.2 ± 12.6 (−0.9, 1.2) | 22% (123) | 49% (270) | 28% (156) |

| Savoury meal foods changeda | 549 | −1.2 ± 13.2 (−2.3, −0.9) | 24% (133) | 50% (277) | 25% (139) |

| Fruit intake changed | 549 | 7.3 ± 18.0 (5.7, 8.8) | 16% (87) | 36% (196) | 48% (266) |

| Vegetable intake changed | 549 | 9.0 ± 16.8 (7.6, 10.4) | 11% (63) | 40% (217) | 49% (269) |

Scores ranged from ‘-50 = I eat a lot less’ to ‘50 = I eat a lot more’, with ‘50 = I eat the same amount’.

Percentages were computed based on scores ≤ -6 = decreased intake; −5 to 5 = no change; ≥6 = increased intake.

Different sample sizes are due to participants dropping out of the survey.

Note.

Average scores computed from responses to individual food items, high energy dense foods.

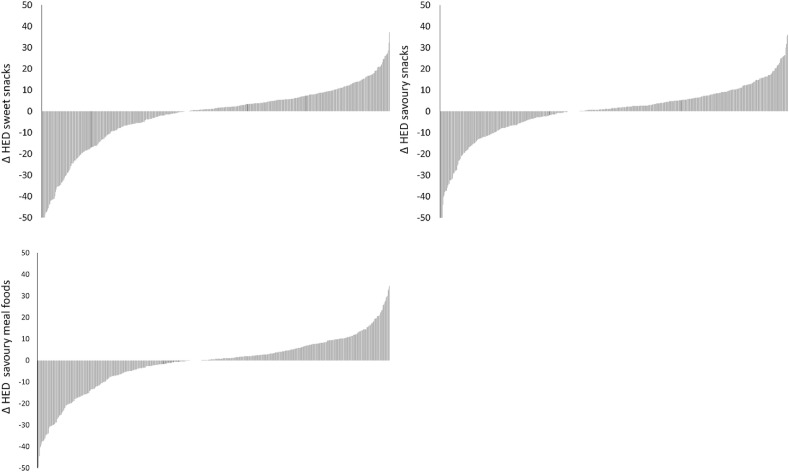

For reported changes to specific food groups, participants reported greater increases of fruit and vegetable intake compared to HED sweet and savoury foods (p < .001). Reported changes for HED sweet and savoury foods (average scores of individual items) were also significantly lower compared to overall snack changes (p < .001). Despite lower mean scores, at least a quarter of participants reported increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods (see Table 3). This individual variability in reported changes to HED sweet and savoury foods is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Individual variability in reported changes (Δ) to high energy dense (HED) sweet (top left) and savoury (top right = snacks, bottom left = meal) foods (n = 549). Participants ranked by order of change on the x-axis.

5.4. Eating behaviour traits as predictors of changes to HED sweet and savoury food intake

Linear regression models identifying the eating behaviour traits that most predict changes to HED sweet and savoury foods are shown in Table 4 . Low craving control was the strongest predictor of increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods. Lower cognitive restraint also significantly predicted increased intake of HED sweet snacks and HED savoury meal foods, but did not significantly predict changes in HED savoury snack intake. Gender, country and habitual food intake were non-significant predictors in each model, except for habitual HED sweet food intake. For HED sweet snacks, lower habitual HED sweet intake significantly predicted greater increases in HED sweet food intake. In all models, eating behaviour traits explained between 6% and 12% of the variance in reported changes to HED sweet and HED savoury foods during the COVID-19 lockdown. Of note, food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, emotional overeating, emotional undereating and satiety responsiveness were not significant predictors in any of the models.

Table 4.

Stepwise linear regressions for eating behaviour traits regressed on to changes for HED sweet snacks, HED savoury snacks and HED savoury meals (n = 499).

| Outcome variable | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| HED sweet snacks | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Constant | 1.25 | 1.37 | |

| Habitual sweet food intake | −1.77 | 0.78 | -.10* |

| Step 2 | |||

| Constant | 13.20 | 2.08 | |

| Habitual sweet food intake | −2.53 | 0.75 | -.14** |

| Craving control | −0.20 | 0.03 | -.32*** |

| Step 3 | |||

| Constant | 19.52 | 3.46 | |

| Habitual sweet food intake | −2.78 | 0.75 | -.16*** |

| Craving control | −0.21 | 0.03 | -.33*** |

| Cognitive restraint | −0.40 | 0.18 | -.10* |

| HED Savoury snacks | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Constant | 7.17 | 1.35 | |

| Craving control | -.13 | 0.02 | -.25*** |

| HED Savoury meal foods | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Constant | 6.76 | 1.41 | |

| Craving control | -.15 | 0.03 | -.26*** |

| Step 2 | |||

| Constant | 11.48 | 2.69 | |

| Craving control | −0.16 | 0.03 | -.27*** |

| Cognitive restraint | −0.32 | 0.16 | -.09* |

Note.

Gender (male, female), country (UK, non-UK) and habitual dietary intake (stepwise method) were entered as covariates in step 1, followed by all eating behaviour traits in step 2 (stepwise method).

For HED sweet snacks: R2 = 0.01, p = .02 for Step 1; R2 = 0.11, p < .001 for Step 2; R2 = 0.12, p < .001 for Step 3. For HED savoury snacks: R2 = 0.06, p < .001. For HED savoury meal foods, R2 = 0.07, p < .001 for Step 1; R2 = 0.08, p < .001 for Step 2.

*p < .05.

***p < .001.

HED = high energy dense.

B = unstandardized coefficient; B SE = unstandardized coefficient standard error; β = standardised coefficient.

5.5. Coping response as a moderator of the relationship between craving control and increased HED sweet and savoury food intake (not pre-registered)

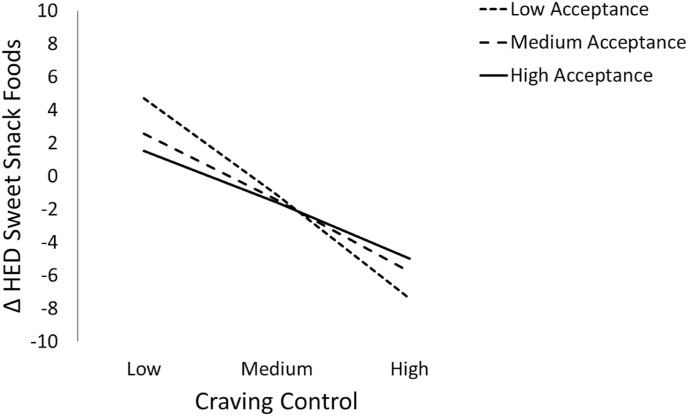

As craving control was the eating behaviour trait that most strongly predicted changes to HED sweet and savoury food intake, moderation analyses were conducted to assess whether coping strategies moderate the conditional effects of craving control on changes to food intake. There was no evidence that acceptance, active coping or positive reframing moderated the relationship between craving control and changes to HED savoury foods (snacks and meals; largest t: b = .02, t(488) = 1.26, p = .21, see Supplementary Materials, Tables 1–8). Active coping and positive reframing also did not significantly moderate the relationship between craving control and changes to HED sweet snacks (largest t: b = −.01, t(488) = −0.75, p = .45). However, for changes to HED sweet snack intake, the interaction between acceptance and craving control was significant (see Table 5 ). Lower craving control was a significant predictor of greater HED sweet snack intake at low (16th; b = −0.24, t(488) = −6.49, p < .001), medium (50th b = −0.17, t(488) = −5.53, p < .001) and high (84th percentile; b = −0.13, t(488) = −3.14, p = .002) levels of acceptance. However, as shown in Fig. 2 this relationship was most pronounced for low acceptance scores, and least pronounced for high acceptance scores. Specifically, participants scoring the lowest in craving control and the lowest in acceptance reported the greatest increases in HED sweet foods. Whereas, medium and high acceptance scores acceptance attenuated the conditional effect of low craving control on HED sweet snack intake.

Table 5.

Moderated regression analysis: interaction of craving control and acceptance coping on changes to HED sweet snack intake.

| Effects | B | SE | t | p | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ HED SW snack intake | 0.12 | 10.58 | 6 | 487 | <.001 | ||||

| Craving control | −0.43 | 0.12 | −3.58 | .0004 | |||||

| Acceptance | −2.11 | 1.09 | −1.94 | .0529 | |||||

| Craving control x acceptance | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.006 | .0454 | |||||

| Gender | 1.25 | 1.43 | 0.87 | .3845 | |||||

| Country | −0.45 | 1.65 | −0.27 | .7846 | |||||

| Habitual sweet snack intake | −2.57 | 0.75 | −3.41 | .0007 |

Note.

HED SW snack intake = high energy dense sweet snack intake.

B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = unstandardized coefficient standard error.

Fig. 2.

Conditional effects of craving control on high energy dense (HED) sweet snack food intake at low, medium, and high values of acceptance coping.

Note. Scores for changes to sweet snack intake ranged from −

50 to 50.

6. Discussion

This study aimed to assess reported changes to food intake (changes to overall amount eaten and for HED sweet and savoury foods) during the COVID-19 lockdown and identify the eating behaviour traits that increase susceptibility to increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods. The study also aimed to explore whether adopting coping strategies linked with reduced distress (active coping, acceptance and positive reframing) would moderate the relationship between eating behaviour traits and changes to food intake. In relation to the first aim, overall, almost half of the participants (48%) reported increased amounts of food intake in response to the UK lockdown. The remaining sample reported either no changes to the amount of food consumed or reported consuming less since the COVID-19 lockdown. Comparison of reported changes to snacks versus meals, showed that participants were more likely to report increased snack intake than increased meal intake. The amount eaten at meals was also more likely to stay the same than snacks. On average, there was an increase in fruit and vegetable intake. Mean changes to HED sweet and savoury foods were low indicating that based on average scores there were minimal changes to the intake of these foods. However, there was large individual variability in reported changes to HED sweet and savoury foods, with 25-28% of participants reporting an increase in the amount of HED sweet and savoury foods consumed. This variability was partly explained by individual differences in eating behaviour traits (aim 2). Specifically, linear regressions showed that low craving control was the strongest predictor of increased HED sweet and savoury snack foods. For HED sweet snacks and HED savoury meals, lower cognitive restraint was also associated with increased intake. These models explained 6–12% of the variance in changes to the amount consumed in response to the COVID-19 lockdown. Finally (aim 3), moderation analysis revealed that acceptance significantly moderated the relationship between craving control and changes to HED sweet snack intake. While participants with the lowest craving control reported the greatest intake in HED sweet snacks, those scoring high in acceptance reported less increases in intake compared to participants scoring low in acceptance. As such adopting an accepting coping strategy appears to buffer to some extent, the negative association between low craving control and increased HED sweet food intake. There was no evidence that coping strategies moderated the relationship between craving control and changes to HED savoury snack and meal intake. Each of these findings will now be discussed.

The finding that almost half of participants reported increased amounts of food intake and most reported increased intake of snack foods since the lockdown aligns with emerging evidence that COVID-19 lockdowns can be a time of high risk for increased food intake. Early reports have indicated increased food intake in response to COVID-19 lockdowns (Ammar et al., 2020). This increased food intake may reflect an increased drive for comfort foods to soothe negative feelings such as stress and boredom experienced in response to the pandemic (Finch & Tomiyama, 2015). Indeed, multiple studies have shown that stress increases food intake, especially for energy dense snacks (Adam & Epel, 2007; Epel et al., 2001; Jane Wardle et al., 2000), and snacking reduces negative affect induced by stress (e.g. Wouters, Jacobs, Duif, Lechner, & Thewissen, 2018). Early reports indicated that some people increased food intake in an effort to reduce COVID-19 related stress, boredom and feelings of emptiness (Cherikh et al., 2020). However, in the current study not all participants reported increased food intake. A substantial proportion of participants reported either no changes or reductions in overall intake and snack intake. Such varied dietary changes in response to COVID-19 reflect other studies also reporting that a subgroup of participants reported reduced intake or no changes in intake during lockdown (Allabadi et al., 2020; Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020). As such, the current findings confirm that COVID-19 lockdowns can be a risky time for some people to increase food intake, but there is large individual variability in responses with a substantial proportion of participants reporting no changes or reduced food intake.

The current study extends previous research on dietary changes in response to COVID-19 by identifying the eating behaviour traits linked with increased susceptibility to increased intake of HED sweet and savoury snack foods. While some research has identified characteristics linked with greater food intake in response to COVID-19, including being female, scoring high in anxiety and depression, having a poor diet quality prior to the COVID-19 lockdown (Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020) and a higher self-reported BMI (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Sidor & Rzymski, 2020), at the time of conducting this study, no research had reported on the eating behaviour traits. For the first time, this study identified the importance of craving control as a main predictor of increased susceptibility to increased intake of HED sweet and savoury foods during the COVID-19 lockdown. While experiences of cravings are commonly reported not all cravings result in food intake (Hill, 2007). Lower ability to control cravings is associated with increased binge eating, tendency to eat opportunistically (Dalton et al., 2015) and less weight loss (Smithson & Hill, 2017). A high number of participants reported increased cravings during the COVID-19 lockdown people, and as such, the ability to control these cravings was important to prevent increased intake of commonly craved HED sweet and savoury snacks (Hill & Heatonbrown, 1994). This finding has important implications and suggests that COVID-19 dietary interventions should target improving craving control in people susceptible to increased HED sweet and savoury snack intake. Indeed, a meta-analysis of 69 laboratory based studies has shown that strategies such as imagining food cues and inhibitory control training reduces cravings and reduces food intake (Wolz, Nannt, & Svaldi, 2020). It will be important for future studies to test whether such strategies are also effective for reducing intake for HED sweet and savoury foods during lockdowns. Such evidence is needed to inform public health guidance on how to maintain a healthy diet during COVID-19 lockdowns. Current guidance advises people to reduce sugar intake, but provides no advice on how to manage cravings (World Health Organization, 2020a). Generating evidence to inform such advice is especially important given that future COVID-19 outbreaks and regional and national lockdowns across the world are likely (Xu & Li, 2020).

In addition to craving control, this study also found that high cognitive restraint predicted lower increases in intake of HED sweet snacks and HED savoury meals during the COVID-19 lockdown (although to a lower extent than craving control). This aligns with previous work showing that cognitive restraint, as measured by the TFEQ is associated with improved control over eating, such as lower energy intake, lower fat intake and lower cravings for energy dense foods (for a review see:Bryant et al., 2019). As such, low scores on cognitive restraint can be used to identify people at risk of increasing intake of HED sweet and savoury snack foods during COVID-19 lockdowns, and appropriate interventions applied.

Unexpectedly, none of the AEBQ subscales significantly predicted changes to HED sweet and savoury food intake. Although greater food responsiveness, emotional overeating and lower emotional undereating were significantly associated with greater reported increases in HED sweet snack foods, these correlations were small and were not significant predictors of changes to HED sweet snack intake. The AEBQ used a 5-point response scale and it is possible that in this study, this restricted range of responses did not allow sufficient variability in scores in detect variability between participants. Future research will benefit by extending the response scale (provided revised response scales are validated) or opting for questionnaires more widely used to assess traits linked with increased susceptibility such as trait disinhibition (Bryant et al., 2019) and trait binge eating (M. Dalton & Finlayson, 2014; Gormally, Black, Daston, & Rardin, 1982). In the current study, the AEBQ was selected over these other measures because it allows for multiple traits to be assessed within a short questionnaire.

Another unique finding reported here which needs to be interpreted with caution, is that coping strategies, specifically acceptance was identified as a protective factor to limit the conditional effects of craving control on increased HED sweet snack food intake. Previous research has shown that scoring high in acceptance coping strategy is associated with reduced psychological distress (Kato, 2015). In the current study, adopting an acceptance coping response may have minimised psychological distress and therefore reduced drives to eat and consume sweet foods. Further research is needed to replicate this finding (especially as the differences in the slopes for each level of acceptance appear small) but it should be noted that this finding aligns with acceptance-based strategies for promoting controlled food intake (Alberts et al., 2013; Forman et al., 2007; Palmeira, Cunha, & Pinto-Gouveia, 2019; Schumacher et al., 2017).

However, it is important to note that acceptance only moderated the relationship between craving control and HED sweet food intake, and did not extend to HED savoury snacks and meals. This might be due to psychological distress tending to increase intake of sweet snacks rather than savoury foods (Wardle & Beales, 1987), meaning that people are in more need of coping strategies to control intake of HED sweet foods over savoury foods during times of high psychological distress. Additionally, positive reframing and active coping which are two other coping responses linked with reduced distress (Kato, 2015) did not moderate the relationship between craving control and changes to HED sweet or savoury foods. Nevertheless, the finding that acceptance coping strategies buffer the negative impact on craving control on HED sweet food intake informs future interventions aimed at tackling susceptibility to increased food intake during viral lockdowns. Future trials evaluating the effectiveness of acceptance-based interventions on HED sweet food intake under lockdown conditions are currently needed before this strategy can be integrated into public health recommendations and clinical practice.

Of note too, although not the primary focus of this report, the results reported here showed increased intake of fruits and vegetables during the COVID-19 lockdown. This differs to previous findings reporting reduced fruit and vegetable intake adults (Matsungo & Chopera, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2020). This might be due to the timing that the survey was administered. Previous studies assessed changes to food intake in the first few weeks of lockdown (e.g. Mitchell et al., 2020), whereas in this study participants completed the survey during the later phases of the lockdown. It is possible that there was more stability in food supply and more adaptation to the lockdown which supported more fruit and vegetable intake in this study compared to previous studies.

There are several limitations to this research that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, in line with the majority of COVID-19 research on eating behaviour (e.g. Ammar et al., 2020; Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020; Sidor & Rzymski, 2020), this study relied on self-reported food intake. It is well documented that self-report dietary measures tend be underestimated, especially in participants with higher BMIs (Heitmann & Lissner, 1995). However, associations reported between different foods and eating behaviour traits indicated that the measures used were sensitive to detect variability in responses as they aligned with expected associations [e.g. HED sweet food intake positively correlated with HED savoury snack intake and negative correlated with craving control (Dalton et al., 2015], suggesting validity in the measures used. Secondly, based on the measures collected, it is not possible to quantify the amount that food intake changed using standard measurements (e.g. energy intake). As self-report data was collected, rather than retrospectively assessing food intake prior to the lockdown and comparing this to reported food intake during the lockdown, we chose to collect subjective ratings of changes to food intake on a 100-point scale. It would be valuable to validate the use of this scale when the opportunity permits and research laboratories begin to open again after the COVID-19 lockdown (due to time pressures to collect data during the lockdown it was not possible to validate or pre-test the survey prior to data collection). The survey also assessed a restricted range of foods and grouped these into food types. As such this report was unable to detail and identify specific food items that participants were most likely to report overconsuming. Thirdly, this study included no measure of subjective stress, so we are unable to confirm whether participants scoring higher in acceptance coping strategies reported lower levels of stress compared to participants scoring lower in acceptance. This decision was made because at the time of devising the survey, there were no validated COVID-19 stress scales. Given the nature of survey-based research, there were constraints on the number of measures that could be included in the survey and measuring coping responses to the lockdown situation was selected over a subjective stress measure. Fourthly, while a range of recruitment methods were used, most of the sample were White, well educated, indicated having a relatively high household income (41% ≥ £40 000), reported a healthy weight status and were not home schooling. As such, the findings may not generalise to other individuals from non-White ethnicities, lower socioeconomic status groups, those with obesity and to individuals who may have been most impacted by COVID-19 in terms of managing a change in roles and responsibilities (e.g. home schooling, balancing work and childcare). This is particularly important considering that the health risks and impacts of COVID-19 are greater for people with a higher BMI and from BAME groups (Public Health England, 2020). As such it is highly recommended that future research focuses on recruiting and including participants from these high risk and under researched groups. Finally, it is important to consider that the data collected is cross-sectional. While the eating behaviour trait questionnaires used have been shown to be valid measurements of stable traits (Dalton et al., 2015, 2017; Hunot et al., 2016; Karlsson et al., 2000), without pre-lockdown an explanation based on reverse causality cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, within a sample of mostly white, educated, not low income, and not home schooling participants, this study identified the role of craving control as an important predictor of increased HED sweet and savoury food intake in response to the UK COVID-19 lockdown. The study also showed that the increased HED sweet food intake reported in people scoring low in craving control was reduced in people who adopted an acceptance coping strategies. Strategies that promote improved craving control and acceptance coping strategies should be further investigated as targets for future interventions to promote controlled food intake during viral lockdowns.

Author contributions

NB conceived and designed the study with contributions from all authors. LS set up the survey and led the data collection and all authors contributed to recruitment of participants. NB performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University of Sheffield's Ethics Committee # 300 420.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abramson E.E., Stinson S.G. Boredom and eating in obese and non-obese individuals. Addictive Behaviors. 1977;2(4):181–185. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(77)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam T.C., Epel E.S. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior. 2007;91(4):449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler N.E., Stewart J. Psychosocial research notebook. 2007. The MacArthur scale of subjective social status.http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/subjective.php Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts H.J.E.M., Mulkens S., Smeets M., Thewissen R. Coping with food cravings. Investigating the potential of a mindfulness-based intervention. Appetite. 2010;55(1):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts H.J.E.M., Thewissen R., Middelweerd M. Accepting or suppressing the desire to eat: Investigating the short-term effects of acceptance-based craving regulation. Eating Behaviors. 2013;14(3):405–409. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allabadi H., Dabis J., Aghabekian V., Khader A., Khammash U. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on dietary and lifestyle behaviours among adolescents in Palestine. Dynamics of Human Health. 2020;7 [Google Scholar]

- Ammar A., Brach M., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L.…Ahmed M. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on physical activity and eating behaviour Preliminary results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online-survey. Nutrients. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell J.E., Stubbs R.J., Golding C., Croden F., Alam R., Whybrow S.…Lawton C.L. Resistance and susceptibility to weight gain: Individual variability in response to a high-fat diet. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;86(5):614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant E.J., Rehman J., Pepper L.B., Walters E.R. Obesity and eating disturbance: The role of TFEQ restraint and disinhibition. Current Obesity Reports. 2019;8(4):363–372. doi: 10.1007/s13679-019-00365-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4(1):92. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherikh F., Frey S., Bel C., Attanasi G., Alifano M., Iannelli A. Behavioral food addiction during lockdown: Time for awareness, time to prepare the aftermath. Obesity Surgery. 2020;30:3585–3587. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04649-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen L. Craving for sweet carbohydrate and fat‐rich foods–possible triggers and impact on nutritional intake. Nutrition Bulletin. 2007;32:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton M., Finlayson G. Psychobiological examination of liking and wanting for fat and sweet taste in trait binge eating females. Physiology & Behavior. 2014;136:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton M., Finlayson G., Hill A., Blundell J. Preliminary validation and principal components analysis of the Control of Eating Questionnaire (CoEQ) for the experience of food craving. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2015;69(12):1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton M., Finlayson G., Walsh B., Halseth A., Duarte C., Blundell J. Early improvement in food cravings are associated with long-term weight loss success in a large clinical sample. International Journal of Obesity. 2017;41(8):1232–1236. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Sutin A., Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/qd5z7/ Accessed July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy M., Druesne-Pecollo N., Esseddik Y., de Edelenyi F.S., Alles B., Andreeva V.A.…Egnell M. medRxiv; 2020. Diet and physical activity during the COVID-19 lockdown period (March-May 2020): Results from the French NutriNet-sante cohort study.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.04.20121855v1 Accessed July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attinà A., Cinelli G.…Scerbo F. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P.D. Cambridge University Press; 2010. The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. [Google Scholar]

- Epel E., Lapidus R., McEwen B., Brownell K. Stress may add bite to appetite in women: A laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch L.E., Tomiyama A.J. Comfort eating, psychological stress, and depressive symptoms in young adult women. Appetite. 2015;95:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson G., Cecil J., Higgs S., Hill A., Hetherington M. Susceptibility to weight gain. Eating behaviour traits and physical activity as predictors of weight gain during the first year of university. Appetite. 2012;58(3):1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman E.M., Hoffman K.L., McGrath K.B., Herbert J.D., Brandsma L.L., Lowe M.R. A comparison of acceptance- and control-based strategies for coping with food cravings: An analog study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(10):2372–2386. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz M.S., MacKinnon D.P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormally J., Black S., Daston S., Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K.D., Sacks G., Chandramohan D., Chow C.C., Wang Y.C., Gortmaker S.L., et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. The Lancet. 2011;378(9793):826–837. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60812-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Guilford publications; 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- Heitmann B.L., Lissner L. Dietary underreporting by obese individuals--is it specific or non-specific? British Medical Journal. 1995;311(7011):986–989. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7011.986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A.J. Symposium on 'molecular mechanisms and psychology of food intake' - the psychology of food craving. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2007;66(2):277–285. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A.J., Heatonbrown L. The experience of food craving: A prospective investigation in healthy women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38(8):801–814. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A.J., Weaver C.F., Blundell J.E. Food craving, dietary restraint and mood. Appetite. 1991;17(3):187–197. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(91)90021-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunot C., Fildes A., Croker H., Llewellyn C.H., Wardle J., Beeken R.J. Appetitive traits and relationships with BMI in adults: Development of the adult eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite. 2016;105:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J., Persson L.O., Sjostrom L., Sullivan M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24(12):1715–1725. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. Frequently used coping scales: A meta-analysis. Stress and Health. 2015;31(4):315–323. doi: 10.1002/smi.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. Springer publishing company; 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. [Google Scholar]

- Litman J.A. The COPE inventory: Dimensionality and relationships with approach-and avoidance-motives and positive and negative traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41(2):273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn C., Wardle J. Behavioral susceptibility to obesity: Gene–environment interplay in the development of weight. Physiology & Behavior. 2015;152:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe M.R., Butryn M.L. Hedonic hunger: A new dimension of appetite? Physiology & Behavior. 2007;91(4):432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madans J.H., Loeb M.E., Altman B.M. Measuring disability and monitoring the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: The work of the Washington group on disability statistics. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S4-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallan K.M., Fildes A., Garcia X.d. l.P., Drzezdzon J., Sampson M., Llewellyn C. Appetitive traits associated with higher and lower body mass index: Evaluating the validity of the adult eating behaviour questionnaire in an Australian sample. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017;14 doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0587-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsungo T.M., Chopera P. medRxiv; 2020. The effect of the COVID-19 induced lockdown on nutrition, health and lifestyle patterns among adults in Zimbabwe.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.16.20130278v1 Accessed July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell E.S., Yang Q., Behr H., Deluca L., Schaffer P. medRxiv; 2020. Self-reported food choices before and during COVID-19 lockdown.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.15.20131888v1 Accessed July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan A.A., Luben R.N., Bhaniani A., Parry-Smith D.J., O'Connor L., Khawaja A.P., et al. A new tool for converting food frequency questionnaire data into nutrient and food group values: FETA research methods and availability. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Digital Statistics on obesity, physical activity and diet. 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/england-2020 England, 2020. Accessed September 2020.

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C.…Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;78:185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver G., Wardle J. Perceived effects of stress on food choice. Physiology & Behavior. 1999;66(3):511–515. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira L., Cunha M., Pinto-Gouveia J. Processes of change in quality of life, weight self-stigma, body mass index and emotional eating after an acceptance-, mindfulness- and compassion-based group intervention (Kg-Free) for women with overweight and obesity. Journal of Health Psychology. 2019;24(8):1056–1069. doi: 10.1177/1359105316686668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England Excess Weight and COVID-19. Insights from new evidence. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/907966/PHE_insight_Excess_weight_and_COVID-19__FINAL.pdf Accessed September 2020.

- Robinson M.A. Using multi‐item psychometric scales for research and practice in human resource management. Human Resource Management. 2018;57(3):739–750. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E., Gillespie S.M., Jones A. Weight‐related lifestyle behaviors and the COVID‐19 crisis: An online survey study of UK adults during social lockdown. Obesity Science & Practice. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1002/osp4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe L.S., Rolls B.J. Which strategies to manage problem foods were related to weight loss in a randomized clinical trial? Appetite. 2020;151 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104687. 104687-104687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher S., Kemps E., Tiggemann M. Acceptance- and imagery-based strategies can reduce chocolate cravings: A test of the elaborated-intrusion theory of desire. Appetite. 2017;113:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government . 2020. Scottish index of multiple deprivation 2020 v2 postcode lookup file.https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020v2-postcode-look-up/ [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M., McBride O., Murphy J., Miller J.G., Hartman T.K., Levita L.…Stocks T.V. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and COVID-19 related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/hb6nq?fbclid=IwAR2-oeNKPdDs89ThulzLqAjgxq51dag7bZrwXsJ-34ue3EcdqChJ1hWc_Bw Accessed July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sidor A., Rzymski P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1657. doi: 10.3390/nu12061657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithson E.F., Hill A.J. It is not how much you crave but what you do with it that counts: Behavioural responses to food craving during weight management. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017;71(5):625–630. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StatsWales Welsh index of multiple deprivation. 2019. https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Community-Safety-and-Social-Inclusion/Welsh-Index-of-Multiple-Deprivation Hentet July 2020 fra. Accessed July 2020.

- Swinburn B.A., Sacks G., Hall K.D., McPherson K., Finegood D.T., Moodie M.L., et al. Obesity 1 the global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B.G., Fidell B.G. 5th ed. utg. Pearson Education, Inc; Boston: 2007. Using multivariate statistics. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government English indices of deprivation 2019. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 Hentet July 2020 fra. Accessed July 2020.

- UK Government Guidance Staying alert and safe (social distancing) 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/staying-alert-and-safe-social-distancing/staying-alert-and-safe-social-distancing.%20Retrieved%20on%2015/05/20 Hentet fra. Accessed July 2020.

- Wardle J., Beales S. Restraint and food-intake - an experimental study of eating patterns in the laboratory and in normal life. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1987;25(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J., Steptoe A., Oliver G., Lipsey Z. Stress, dietary restraint and food intake. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;48(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolz I., Nannt J., Svaldi J. Laboratory-based interventions targeting food craving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2020;21(5) doi: 10.1111/obr.12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization #Healthyathome: Healthy diet. 2020. https://www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---healthy-diet Hentet fra. Accessed July 2020.

- World Health Organization . 2020. Obesity and overweight.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight Hentet July 2020 fra. Accessed July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters S., Jacobs N., Duif M., Lechner L., Thewissen V. Negative affective stress reactivity: The dampening effect of snacking. Stress and Health. 2018;34(2):286–295. doi: 10.1002/smi.2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Li Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10233):1321–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30845-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data