Abstract

Carbon-centered radicals can be stabilized by delocalization of their spin density into the vacant p orbital of a boron substituent. α-Vinyl boronates, in particular pinacol (Bpin) derivatives, are excellent hydrogen atom acceptors. Under H2, in the presence of a cobaloxime catalyst, they generate α-boryl radicals; these species can undergo 5-exo radical cyclizations if appropriate double bond acceptors are present, leading to densely functionalized heterocycles with tertiary substituents on Bpin. The reaction shows good functional group tolerance with wide scope, and the resulting boronate products can be converted into other useful functionalities.

Keywords: Cycloisomerization, Hydrogen Atom Transfer, α-Boryl Radical, radical cyclization

Graphical Abstract

Carbon-centered radicals can be stabilized by delocalization of their spin density into the vacant p orbital of a boron substituent. α-Vinyl boronates, in particular derivatives of pinacol (Bpin), are therefore excellent hydrogen atom acceptors, generating α-boryl radicals from H2 in the presence of a cobaloxime catalyst. These radicals undergo 5-exo radical cyclizations onto appropriate double bonds, eventually furnishing densely functionalized heterocycles with tertiary substituents on Bpin. The reaction shows good functional group tolerance, and the resulting unsaturated boronates can be easily converted into other useful functionalities.

Radical cyclizations are an efficient method for introducing molecular complexity in a single step.1 Our groups have long been interested in the applications of H• transfer from transition-metal hydrides onto various olefins — especially those that carry our radical cyclizations.2 We now report that H• transfer to α-vinyl boronates from H2 in the presence of a cobaloxime catalyst can carry out intramolecular cycloisomerizations. Our method provides rapid access to functionalized five-membered heterocycles such as pyrrolidines, which are present in many natural products such as those shown in Figure 1.3

Figure 1.

Natural products with pyrrolidine moiety.

Organoboron compounds are intermediates for many useful transformations, including the frequently used Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction for C-C bond formation.4 Vinyl boronates are easily accessible through transition-metal-catalyzed borylation of alkynes,5 vinyl halides6 or allenes,7 can react via ionic or radical pathways, and have recently attracted much attention. Attack on the vinyl boronates by either Pd(II) (Morken)8a or an alkyl radical (Studer8b and Aggarwal8c) can induce 1,2 migration of R (alkyl or aryl) from the boron to the α-carbon, and bring about the formation of two C─C bonds and the difunctionalization of the original alkene.8

The empty p orbital of a boron atom can stabilize an adjacent carbon-centered radical through π-conjugation.9 Calculations indicate that the radical stabilization energy (RSE) of BH2-CH2• is about 11 kcal/mol, but the oxygens of a pinacolate (pin) ligand also interact with the empty boron orbital and decrease its ability to delocalize the unpaired electron; the RSE of Bpin-CH2• is thus only about 5 kcal/mol (Scheme 1).10

Scheme 1.

Radical Stabilization by Adjacent Boron

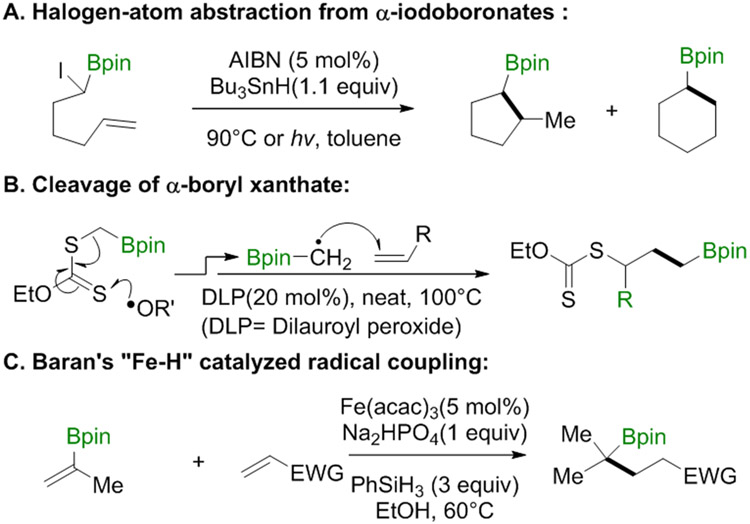

α-Boryl radicals are typically formed as intermediates in radical chain reactions. Halogen-atom abstraction from α-haloboronates, as shown in Scheme 2A, is generally performed with Bu3Sn• (which requires the use of a toxic tin hydride).11 The related reaction in Scheme 2B, reported by Zard and co-workers, cleaves a C─S bond in a boryl xanthate by adding an initiating (or a chain-carrying) radical to thiocarbonyl of the xanthate.12 The Baran group has generated boryl radicals by H• transfer to olefins, apparently from an in situ generated Fe hydride;13 the radicals then add to electron-deficient olefins, as shown in Scheme 2C.14

Scheme 2.

Generation and Application of α-Boryl Radicals

We have also generated radicals by H• transfer to olefins, but we have obtained the H• from H2. Substrates have included enol ethers,2c acrylamides,15 N-vinyl indoles,16 and 1,1-disubstituted (with aryl and CF3) olefins,17 and the transformations of these substrates have included cyclohydrogenations, cycloisomerizations, and hydrodefluorinations. In this article, we demonstrate the generation of boryl radicals by H• transfer from H2 to to vinyl boronates. H2 is a more practical, cheaper, and greener — especially for industrial applications — source of hydrogen atoms than the silanes which have become common in synthetic laboratories.

We have found Co(dmgBF2)2(MeOH)2 (dmg = dimethylglyoximato) to be quite effective as a catalyst for this reaction, and Co(dmgBF2)2(THF)2 even more so. The readily prepared substrate 1a gives the cycloisomerization product 2a (Table 1), surely via the formation of the radical A and its cyclization. No isomerization, hydrogenation or cyclohydrogenation side products have been observed.18 Control experiments (entries 2 and 4) show that both cobalt and H2 are indispensable. (Using several atm of H2 maximizes the generation of the intermediate responsible for H• transfer.19) Co(III)salen shows no catalytic activity, and CpCr(CO)3H/H22a gives a mixture of unidentified products. Screening of concentration, catalyst loading, and solvent gave the following conditions as optimal: 5 mol% Co(dmgBF2)2(THF)2 and 4.8 atm H2 in benzene (0.10 M) at 50 °C for 3 days.

Table 1.

Optimal Conditions for the Cyclization of the α-Vinyl Boronate 1a (eq 1)a

|

Conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 5.0 mol% catalyst C-1, 4.8 atm H2, benzene (0.1M), 50°C, three days.

Determined by 1H NMR with internal standard.

Under 6.1 atm H2.

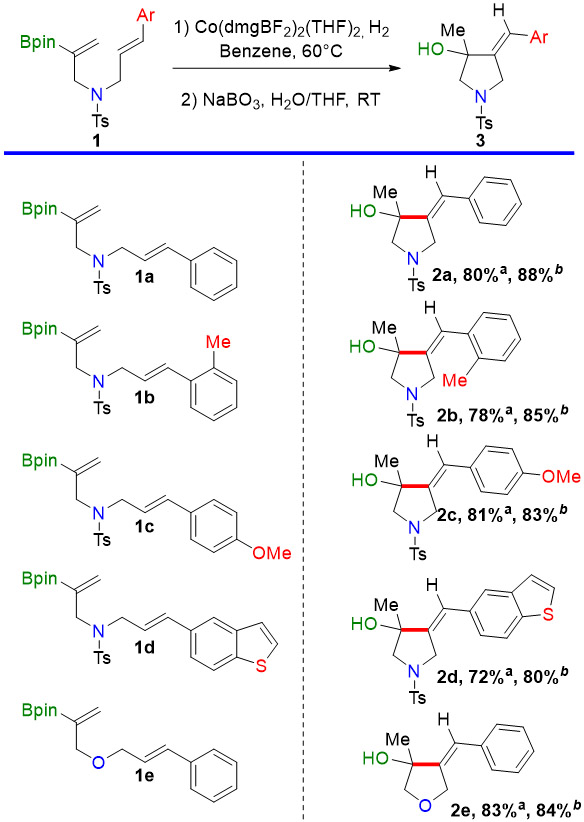

We have explored the scope of our cobaloxime catalyst with other aryl-substituted olefins as radical acceptors. The allylic boranes produced by these cyclizations are generally not stable enough for purification, so we have oxidized them to the allylic alcohols shown in Table 2. Neither steric hindrance (entry 2), nor an electron-donating substituent (entry 3), nor a heterocyclic substituent (entry 4) interfered with the reaction. Good results were also obtained when the nitrogen atom was replaced with an oxygen, making the tetrahydrofuran derivative in entry 5.

Table 2.

Scope of the Cyclization Reaction with an Aryl-substituted Olefin as Radical Acceptora

|

Conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 5.0 mol% Catalyst (C-1), 4.8 atm H2, benzene (0.1M), 50°C, three days.

Yield for cycloisomerization reaction determined by 1H NMR with internal standard.

Isolated yield for the oxidized product based on the cycloisomerized boronate intermediate.

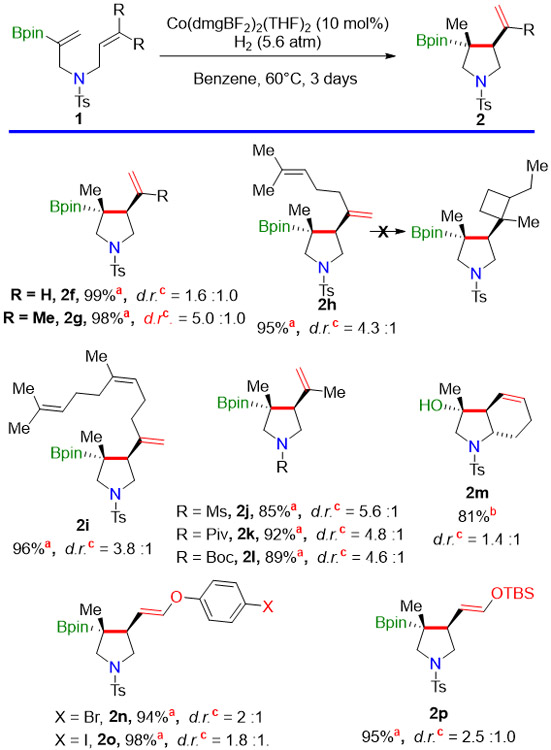

With alkyl substituents on the acceptor olefin, we also obtained cyclization; however, we found that our cobalt catalyst abstracted H• from the less hindered carbon of the cyclized radicals, leading to the cycloisomerized products in Table 3. (These were more stable than the aryl-substituted products, but decomposed upon storage in the refrigerator.)

Table 3.

Scope of the Cyclization Reaction with an Alkyl-substituted Olefin as Radical Acceptora

|

Conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 5.0 mol% Catalyst (C-1), 4.8 atm H2, benzene (0.1M), 50°C, three days.

Yield for cyclization reaction determined by 1H NMR with internal standard

Isolated yield for the oxidized product.

ratio determined by crude 1H-NMR with internal standard.

As the cyclized radicals are less stable than the benzylic ones formed in Table 2, a slightly higher catalyst loading (10 mol%) and H2 pressure (5.6 atm) are required to get complete conversion of the substrate. No second cyclization occurred with the unconjugated diene 1h or the unconjugated triene 1i, presumably because of the strain that would be introduced by a 4-exo cyclization. Varying the substituent on the nitrogen (1j–1l) had little effect on the reactivity of these substrates. Th bicyclic scaffold 2m was easily constructed. Sensitive functionality, including an aryl bromide (2n) ,iodide (2o), and a silyl enol ether (2p), was tolerated under these reaction conditions. The diastereoselectivity of these transformations will be discussed later (vide infra).

The analogous oxygen-containing substrates also worked well (1q-t in Table 4), indeed with enhanced diastereoselectivity. The reaction with 1s can be performed on a 2.0 mmol scale without significant loss of efficiency. The terminal TBS-protected (Z)-allylic alcohol 1u did not cyclize at all, giving only the isomerized substrate.

Table 4.

Scope of the Cyclization Reaction with Oxygen Instead of Nitrogena

|

Conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 5.0 mol% Catalyst (C-1), 4.8 atm H2, benzene (0.1M), 50°C, three days.

Yield for cyclization reaction determined by 1H NMR with internal standard

2.0 mmol scale.

In an effort to understand the why 1u did not cyclize, we prepared a pair of isoelectronic substrates, 1v and 1w, differing only by the substitution of O for NTs. The nitrogen-containing 1v did not observably react under our standard condition, whereas its oxygen analogue 1w largely isomerized to 2w (Scheme 3). We presume that the radicals 1v’ and 1w’ are reversibly formed by the initial H• transfer (under D2 1v undergoes 85% deuterium exchange into its methylene, Scheme 4). However, the C–H of 1v’ is somewhat stronger than the C–H of 1w’: Density Functional Theory calculations (see SI for detail) give a BDFE of 47.6 kcal/mol for 1v’, compared to one of 45.0 kcal/mol for 1w’. (H• transfer to the cobaloxime from either 1w’ or 1v’ is downhill, as the BDFE of the cobaloxime–H bond is 49.6 kcal/mol.20) Removal of H• by CoII should thus be substantially easier for 1w’ than for 1v’, and it is understandable that isomerization will compete more successfully with cyclization for 1w’.

Scheme 3.

Isomerization vs Cycloisomerization

Scheme 4.

Deuterium Exchange into Substrate.

Treatment of 1x with two equiv of CpCr(CO)3D for three days at 50 °C gave about 80% H/D exchange. Collectively, these D incorporation experiments support a reversible HAT mechanism for the generation of α-boryl radicals from vinyl boronates.21

The cyclized alkyl boronates, such as 2s, offer a platform for late-stage functionalization of 5-membered-ring heterocyclic products. For example, 1) 2s can be easily oxidized to an alcohol with peroxides;22 2) Aggarwal’s lithiation method23 can install a furan substituent on the scaffold of 2s; 3) 2s can be converted into its more stable BF3K salt, which can be used for subsequent Suzuki cross-coupling reactions.24

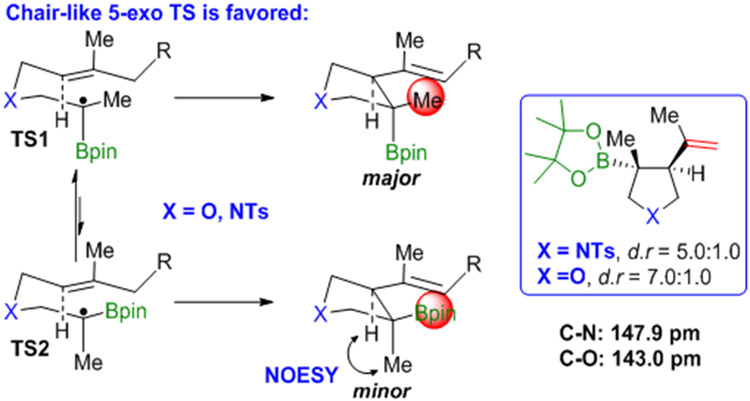

Beckwith and Houk have established a chair-like transition state for 5-exo radical cyclizations (Scheme 5),25 with the bulkier substituent occupying the pseudoequatorial position. The Aggarwal group has recently quantified the A value for different boronic esters,26 and concluded that the A value of Bpin is about 0.4 kcal/mol — much smaller than the A value of a methyl group (which is about 1.7 kcal/mol). The transition state TS1 should thus be favored in our cyclizations, which will lead to the cis diastereomer as the major product; the minor (trans) product has been identified by 2D-NOESY. A shorter C–X (X = O or NTs) bond will lead to a more congested transition state because of an enhanced 1,3-diaxial interaction,27 which in turn will increase the diastereoselectivity. Our experimental results are consistent with this assumption.

Scheme 5.

Origin of diastereoselectivity.

In conclusion, we have developed a cobalt-catalyzed method for the HAT-initiated cycloisomerization of α-vinyl boronates. Our way of generating α-boryl radicals is simple and easy to use, with H2 as the only stoichiometric reagent; it avoids the toxic Bu3SnH and the waste associated with the use of silanes. Pyrrolidine and tetrahydrofuran derivatives are easily made, and the reaction can be done on a large scale. The B─C bond in the cyclized products provides a platform for many late-stage transformations. Finally, deuterium labelling experiments support an HAT-initiated radical mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Synthetic Application of Cyclic Alkylboronates.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award R01GM124295. We thank Dr. Yiting Gu and Dr. Jiawei Chen for helpful discussions and setting up 11B-NMR experiments. Gaussian 09 calculations in this work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by the National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562 through allocation CHE200024 on Comet (San Diego Super Computing Center).

References

- [1] a).Jasperse CP, Curran DP, Fevig TL, Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 1237–1286; [Google Scholar]; b) Romero KJ, Galliher MS, Pratt DA, Stephenson CRJ, Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 7851–7866; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Thomas WP, Schatz DJ, George DT, Pronin SV, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 12246–12250; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ji Y, Xin Z, He H, Gao S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 16208–16212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2] a).Smith DM, Pulling ME, Norton JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 770–771; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hartung J, Pulling ME, Smith DM, Yang DX, Norton JR, Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11822–11830; [Google Scholar]; c) Kuo JL, Hartung J, Han A, Norton JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1036–1039; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Li G, Kuo JL, Han A, Abuyuan JM, Young LC, Norton JR, Palmer JH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7698–7704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Gu Y, Norton JR, Salahi F, Lisnyak VG, Zhou Z, Snyder SA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 9657–9663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3] a).O’Hagan D, Nat. Prod. Rep 2000, 17, 435–446; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bhat C, Kumar A, Asian J. Org. Chem 2015, 4, 102–115; [Google Scholar]; c) Feutren S, McAlonan H, Montgomery D, Stevenson PJ, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1, 2000, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar]

- [4] a).Miyaura N, Suzuki A, Chem. Rev 1995, 95, 2457–2483; [Google Scholar]; b) Neeve EC, Geier SJ, Mkhalid IAI, Westcott SA, Marder TB, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 9091–9161; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Fyfe JWB, Watson AJB, Chem, 2017, 3, 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- [5] a).Jang H, Zhugralin AR, Lee Y, Hoveyda AH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 7859–7871; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Moure AL, Gómez Arrayás R, Cárdenas DJ, Alonso I, Carretero JC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 7219–7222; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Moure AL, Mauleón P, Gómez Arrayás R, Carretero JC, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 2054–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Takahashi K, Takagi J, Ishiyama T, Miyaura N, Chem. Lett 2000, 29, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- [7] a).Meng F, Jung B, Haeffner F, Hoveyda AH, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 1414–1417; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kuang J, Ma S, J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 1763–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8] a).Zhang L, Lovinger GJ, Edelstein EK, Szymaniak AA, Chierchia MP, Morken JP, Science, 2016, 351, 70–74; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kischkewitz M, Okamoto K, Mück-Lichtenfeld C, Studer A, Science, 2017, 355, 936–938; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Silvi M, Sandford C, Aggarwal VK, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 5736–5739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kumar N, Reddy RR, Eghbarieh N, Masarwa A, Chem. Commun 2020, 56, 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10] a).Walton JC, McCarroll AJ, Chen Q, Carboni B, Nziengui R, R., J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 5455–5463; [Google Scholar]; b) Hioe J, Zipse H, Radical Stability—Thermochemical Aspects. Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology Materials 2012; [Google Scholar]; c) Lovinger GJ, Morken JP, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2020, 16, 2362–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Guennouni N, Lhermitte F, Cochard S, Carboni B, Tetrahedron, 1995, 51, 6999–7018. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huang Q, Michalland J, Zard SZ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 16936–16942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13] a).Barker TJ, Boger DL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 13588–13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gotoh H, Sears JE, Eschenmoser A, Boger DL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 13240–13243; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lo JC, Yabe Y, Baran PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 1304–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lo JC, Gui J, Yabe Y, Pan C-M, Baran PS, Nature, 2014, 516, 343–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lorenc C, Vibbert HB, Yao C, Norton JR, Rauch M, ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 10294–10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shi S, Kuo JL, Chen T, Norton JR, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 6171–6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yao C, Wang S, Norton JR, Hammond M, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 4793–4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18] a).Crossley SW, Barabé F, Shenvi RA, Simple, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16788–16791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Matos JLM, Green SA, Chun Y, Dang VQ, G Dushin R, Richardson P, S Chen J, Piotrowski DW, Paegel BM, Shenvi RA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 12998–13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Crossley SW, Obradors C, Martinez RM, Shenvi RA, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 8912–9000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19] a).Li G, Han A, Pulling ME, Estes DP, Norton JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 14662–14665; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li G, Estes DP, Norton JR, Ruccolo S, Sattler A, Sattler W, Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 10743–10747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20] a).Estes DP, Grills DC, Norton JR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 17362–17365; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wise CF, Agarwal RG, Mayer JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 10681–10691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21] a).Sweany RL, Halpern J, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1977, 99, 8335–8337. [Google Scholar]; b) Shevick SL, Wilson CV, Kotesova S, Kim D, Holland PL, Shenvi RA, A. R, Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 12401–12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hussain MM, Li H, Hussain N, Ureña M, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 6516–6524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bonet A, Odachowski M, Leonori D, Essafi S, Aggarwal VK, Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Molander GA, Ellis N, Acc. Chem. Res 2007, 40, 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25] a).Beckwith ALJ, Schiesser CH, Tetrahedron 1985, 41, 3925–3941; [Google Scholar]; b) Spellmeyer DC, Houk KN, J. Org. Chem 1987, 52, 959–974. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fasano V, McFord AW, Butts CP, Collins BSL, Fey N, Alder RW, Aggarwal VK, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 22403–22407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhu H, Leung JCT, Sammis GM, J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 965–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.