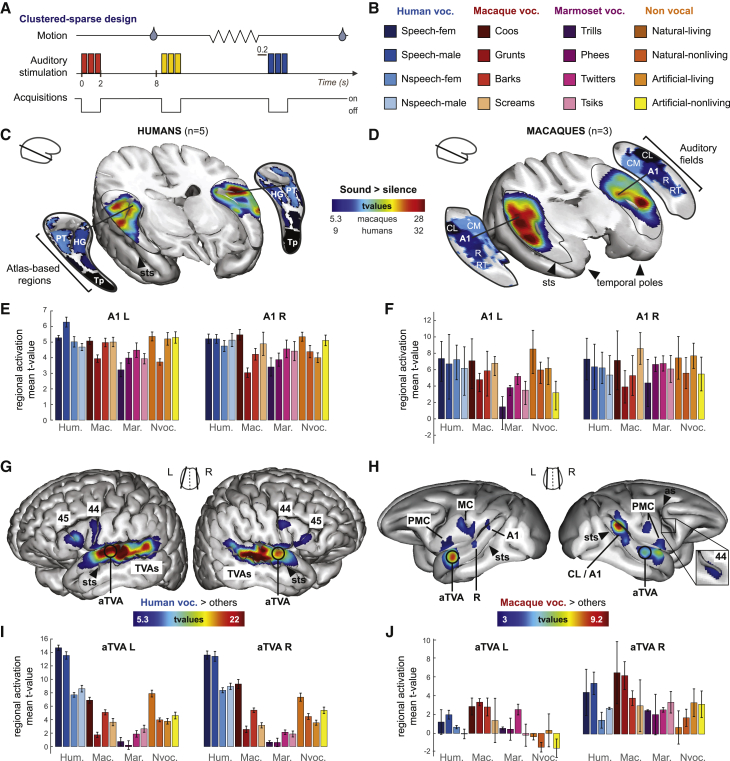

Figure 1.

Auditory cerebral activation in humans and macaques

(A) Scanning protocol. Auditory stimuli were repeated three times in rapid succession during silent intervals between scans; macaques were rewarded with juice after 8-s periods of immobility.

(B) Auditory stimuli. Stimuli consisted of 96 complex sounds from 4 large categories divided into 16 subcategories.

(C and D) Areas with significant (p < 0.05, corrected) activation to sounds versus the silent baseline. t value threshold as indicated under the color bar. (C) Humans. PT, planum temporale; HG, Heschl’s gyrus (from Harvard Oxford atlas); Tp, temporal pole; sts, superior temporal sulcus. (D) Macaques. A1, R, core auditory areas; CL, CM, RT, belt auditory areas from Petkov et al.7

(E and F) Group-averaged regional mean activation (t values) for the 16 sound subcategories compared to silence in (E) humans and (F) macaques. Error bars indicate SEM.

(G and H) CV-selective areas showing greater fMRI signal in response to CVs versus all other sounds. White circles indicate the location of bilateral anterior temporal voice areas in both species. (G) Human voc. > others at p < 0.05 corrected; TVAS, temporal voice areas; FVAs, frontal voice areas; 44-45, corresponding Brodmann areas from Harvard Oxford Atlas. (H) Macaque voc. > others at p < 0.001 uncorrected, p < 0.05 cluster-size corrected; as, arcuate sulcus; MC, motor cortex; PMC, premotor cortex; 44, corresponding Brodmann area from D99 atlas.

(I and J) Group-averaged regional mean activation (t values) for the 16 sound subcategories compared to silence in the aTVAs in (I) humans and (J) macaques.

See also Figures S1–S3 and Table S1.