Abstract

Objectives

To quantify association between in utero/peripartum antiretroviral (IPA) exposure and cognition, i.e. executive function (EF) and socioemotional adjustment (SEA), in school-aged Ugandan children who were perinatally HIV-infected (CPHIV, n = 100) and children who were HIV-exposed but uninfected (CHEU, n = 101).

Methods

Children were enrolled at age 6–10 years and followed for 12 months from March 2017 to December 2018. Caregiver-reported child EF and SEA competencies were assessed using validated questionnaires at baseline, 6 and 12 months. IPA type – combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), intrapartum single-dose nevirapine ± zidovudine (sdNVP ± ZDV), nevirapine + zidovudine + lamivudine (sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC) – or no IPA (reference) was verified via medical records. IPA-related standardized mean differences (SMDs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in cognitive competencies were estimated from regression models with adjustment for caregiver sociodemographic and contextual factors. Models were fitted separately for CPHIV and CHEU.

Results

Among CPHIV children, cART (SMD = ‒0.82, 95% CI: ‒1.37 to ‒0.28) and sdNVP ± ZDV (SMD = ‒0.41, 95% CI: ‒0.81 to ‒0.00) vs. no IPA predicted lower executive dysfunction over 12 months. Intrapartum sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC vs. no IPA predicted executive dysfunction (SMD = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.30–1.31), SEA problems (SMD = 0.63–0.76, 95% CI: 0.00–1.24) and lower adaptive skills (SMD = ‒0.36, 95% CI: ‒0.75–0.02) over 12 months among CHEU. Further adjustment for contextual factors attenuated associations, although most remained of moderate clinical importance (|SMD| > 0.33).

Conclusions

Among CPHIV children, cART and sdNVP ± ZDV IPA exposure predicted, on average, lower executive dysfunction 6–10 years later. However, peripartum sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC predicted executive and SEA dysfunction among CHEU 6–10 years later. These data underscore the need for more research into long-term effects of in utero ART to inform development of appropriate interventions so as to mitigate cognitive sequelae.

Keywords: cognitive function, executive function, HIV-exposed children, in utero ART, maternal ART, socioemotional adjustment

Introduction

With expansion of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) has plummeted by as much as 50% while the population of perinatally HIV-exposed uninfected (CHEU) children has doubled since 1990 [1]. Maternal ART is effective for prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) of HIV [2] but this exposure comes with several known neurodevelopmental risks: low birth weight [3], metabolic dysregulations[4], mitochondrial toxicity [5–8] and neurotoxicity[9,10]. For children born to HIV-infected women, this risk will necessarily continue making higher neurodevelopmental risk a price paid to avert the more adverse outcome of HIV transmission [11,12]. Given this reality, there is a corresponding imperative for long-term surveillance of neurodevelopmental outcomes among in utero/peripartum ART (IPA)-exposed children to determine the extent of impairments and to inform interventions research so as to mitigate them.

Globally, most children with IPA exposure live in sub-Saharan Africa, but specific long-term studies in this setting are few, evidence from available studies are inconsistent and investigations in school-aged children are limited [13–15]. WHO PMTCT guidelines, coverage and scope of IPA exposure among children born to HIV-positive pregnant women varied across HIV treatment eras [16] with possible implications for neurodevelopmental outcomes. For example, a metanalysis of preschool children found worse neurodevelopmental outcomes for children who were perinatally HIV-infected (CPHIV) and CHEU vs. HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) preschoolers, and cognitive outcomes for CHEU were worse with IPA exposure [17]. Among American children enrolled in the surveillance monitoring of ART toxicities (SMARTT), an elevated risk of language impairment was noted in CHEU with combination ART (cART)-based IPA vs. CPHIV at 4 and 5 years old [18] although cognitive and academic outcomes at 5–13 years old were similar between groups [19]. Among Thai and Cambodian children, both CPHIV and CHEU had worse cognition relative to HUU regardless of the timing of ART initiation in pregnancy [20]. Of the studies in Africa, no ART-related differences in cognition were evident among preschool-age children [13,15] or among Cameroonian children aged 6–8 years in a cross-sectional study [14]. Longitudinal studies of IPA-related change in cognition among African HIV-exposed children during school and adolescence are lacking.

Hence, we report on the longer-term association between IPA exposure and deficits in socioemotional adjustment and executive dysfunction by 6–10 years old among HIV-exposed children of HIV-positive women followed for 12 months. We hypothesized that IPA would be associated with worse cognition by the early school-aged years. However, associations between IPA and cognition may vary according to the type of early ART regimen and the HIV status of the exposed child.

Materials and methods

Participants, study context and design

Children who were HIV-unexposed and uninfected (CHUU, n = 97), CHEU (n = 100) and CPHIV (n = 101) aged 6–10 years at enrolment, who were born in a formal health-care setting, and their adult primary caregivers were enrolled as part of a larger study of functional survival with perinatal HIV exposure among 306 children aged 6–10 years from Uganda. [21] Children were enrolled on a first-come, first-served basis from Kawaala Health Centre (KHC), in Kampala, Uganda, between 15 March 2017 and 15 September 2018. Of these, eight children lacking cognition measures were excluded. CPHIV were enrolled from current patients at KHC. CHEU were identified through medical records of HIV-infected adult women cared for at KHC. In addition, an Early Infant Diagnosis (EID) registry was used to identify age-eligible CHEU who remained HIV-free until discharge from the EID programme. Age-eligible CHUU were recruited from KHC’s outpatient department upon presentation for healthcare services and from the social networks – family, friends and neighbours – of already enrolled caregiver–child pairs. Cognitive performance measures in CHUU were used as a reference for standardizing by age and sex the cognitive performance of HIV-exposed children. Because this analysis is specifically focused on investigating the extent to which cognitive trajectory among HIV-exposed children differs based on IPA exposure type/history, CHUU for whom IPA exposure did not apply were excluded. During the study period, HIV prevalence in Kawaala District was 11% vs. a national prevalence of 7.3%.

Eligibility/exclusion criteria

Caregiver eligibility included ≥ 18 years old and affirmative response to being the primary caregiver for a study-eligible child for a period of at least 6 months prior to enrolment. Eligibility criteria for children included: 6–10 years old at enrolment and availability of health records with objective data regarding HIV status of biological mother, mode of birth, full or preterm birth, birth weight, participation in PMTCT services, any/type of ART exposure (if applicable) and HIV status of index child at birth or by date of discharge from the EID programme (if CHEU). Children born in non-clinic settings for whom antenatal register/delivery medical records could not be found were ineligible to participate, as IPA exposure status and the HIV status of the child and birth mother could not be reliably ascertained.

Statement of ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the research ethics review committees of Michigan State University (IRB protocol no. 16–828), Makerere University College of Health Sciences, School of Medicine (Protocol REC REF no. 2017–017) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (protocol no. SS4378). All caregivers gave written informed consent and children provided assent for study participation.

Outcome definition

Two domains of cognition – socioemotional adjustment (SEA) and executive function (EF) – were defined according to caregiver responses to 175 questions in the Behavioral Assessment System for Children (BASC-3) [22] and the shortened 24-item version of Behavior Rated Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) [23] at intake and at 6 and 12 months. At all study assessments, responding caregivers must have cared for the dependent child for at least 6 months. For the vast majority (> 95%) of children, the same respondent caregiver (usually the biological parent or grandparent) completed all time points. Questions were administered by trained interviewers (n = 3) according to a common manual of operations. To maximize interaction rapport, whenever possible, the same interviewer was matched to a caregiver during follow-up. Snacks were provided before each interview session to mitigate the distracting effect of hunger on responses. In the absence of locally normed scores, cognitive measures were internally age- and sex-standardized to performance among CHUU children, i.e. z-scoreit = (scoreit ‒ meant0 (CHUU))/(standard deviationt0(CHUU)) [24].

Four composite SEA scales were defined using information scored according to the BASC-3 manual: externalizing problems composite (EPC), internalizing problems composite (IPC), behavioural symptoms index (BSI) and adaptive skills index (ASI). Higher scores on the EPC, IPC and BSI indicate worse SEA. On the other hand, higher scores in the ASI composite indicate higher SEA. Two EF domains and the corresponding subscales within each domain were defined according to the manufacturer’s instructions: (1) meta-cognition domain (a composite of working memory, task initiation, planning, monitoring and material organization subscales), and (2) the behavioural regulation domain (a composite of inhibition, flexibility and emotional control subscales). In addition, a global executive component score (GEC) was defined as the sum of scores in the meta-cognition and behavioural regulation domains of BRIEF.

Validation and psychometric properties of tools

Respective tools were adapted for cultural context, forward- and back-translated to Uganda as previously described. [24] In a small sample (n = 30 caregivers) at enrolment, each tool was administered twice 14–21 days apart to the same respondent by different interviewers to determine the internal consistency among individual questions and test–retest reliability [25] estimated using the %INTRACC macro [26]. The internal consistency reliability for the BRIEF global executive composite (Cronbach’s α = 0.89), meta-cognition index (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) and behavioural regulation index (Cronbach’s α = 0.68) domains were excellent and acceptable. Test–retest reliability for caregiver responses to questions about EF in their dependent children was excellent [intra-class correlation (ICC) = 0.84–0.90].

All BASC SEA subscales demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α: 0.83–0.91). Test–retest reliability values in the good to excellent range (ICC: 0.51–0.79) confirm that caregivers stably reported relevant behavioral symptoms exhibited by their dependent children over 14–21 days interval.

Perinatal HIV status

Perinatal HIV status was established by 18 months via DNA PCR. Current HIV status of CHEU was confirmed via HIV rapid diagnostic test at enrolment.

IPA exposure

Several landmark ART studies that directly informed the standard of ART care have been implemented in Uganda [27–32]. These efforts, in coordination with Uganda Ministey of Health and global partners, contributed to systemic strengthening of HIV care delivery and harmonization of HIV data collection systems that permit completed and objective determination of IPA exposure in all HIV-exposed children based on routinely recorded medical data. As a function of rapid changes in HIV care and treatment, IPA exposure (if any) and the specific IPA exposure type were determined by the child’s year of birth and the pregnant woman’s CD4 cell count. For pregnant HIV-positive women not yet ARV-eligible according to prevailing CD4 guidelines, three options applied depending on the year of pregnancy: (1) pregnant women received single-dose nevirapine (sdNVP) only at onset of labour and new-born infants received the same at birth; (2) zidovudine (ZDV) to pregnant woman was begun at 28 weeks or shortly thereafter, continued at the same dose in labour with the addition of sdNVP at labour onset, and with their infant receiving sdNVP at birth with 1 week of ZDV; or (3) pregnant woman received ZDV plus lamivudine (3TC) starting at 36 weeks and maintained through 1 week post-partum, with the infant receiving 1 week of ZDV + 3TC [33]. All IPA exposure was abstracted from the antenatal register, ART card or EID register and classified according to maternal exposure status as: no IPA (reference), intrapartum prophylactic sdNVP ± ZDV, intrapartum prophylactic sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC and cART (i.e. two or more antiretroviral drug classes).

Other covariates

Caregiver demographic and behavioural factors: Information on alcohol use (ever vs. never drinker), marital status and perceived social standing using standardized questionnaires [24,34].

Caregiving environment: Caregiver’s socioeconomic status was defined as presence or absence of income and years of formal education. Maternal functioning was defined as a proxy for caregiving quality using the Barkin’s Index [35], and psychosocial stress was measured using the perceived stress scale [36].

Child characteristics: Biological sex (male vs. female) and chronological age (in years) were adjusted for in all analyses. Prematurity (i.e. < 37 weeks’ gestation at birth), 5-min Apgar score < 7, and low birth weight (≤ 2500 g) were abstracted from medical records. Height-for-age at enrolment was calculated.

Current cART regimen and CD4 nadir: These three variables are defined for CPHIV only. Current cART regimen was determined as part of health assessment at enrolment and classified as follows: protease inhibitor (including lopinavir/ritonivir/kaletra), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI, i.e. nevirapine or efavirenz)-based cART or cART-naïve – if child was HIV-infected and not on treatment. Lastly, the lowest CD4 cell count of enrolled children since the beginning of HIV care at KHC was established via medical records.

Statistical analysis

Separate analyses were conducted for CHEU and CPHIV because CPHIV required current ART for HIV management. The time of ART initiation for CPHIV depended on treatment guidelines and severity of illness/immune deficiency, factors that did not apply to CHEU. Caregiver demographic and behavioural factors, caregiving environment, child characteristics, pertinent HIV-treatment related factors (if applicable) and baseline cognitive performance were summarized via means (SDs) for continuous variables, and frequencies (%) for categorical variables. Differences by exposure to ART regimen (any ART vs. none) were evaluated using t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Multivariable linear mixed-effects (LME) models were implemented to estimate early ART exposure-related standardized mean differences (SMDs) in three repeated measures of cognitive outcomes (SEA, EF) over 12 months using SAS PROC MIXED [37]. In all models, confounders (child’s age, sex, relationship with caregiver, caregivers’ age, sex, caregiver depression and socioeconomic status) were adjusted for in light of subject matter knowledge – an approach grounded in causal theory that assures robust non-biased inference [38–42] by recognizing child perinatal risk factors as causal path variables influenced by maternal IPA [3–10]. Among CPHIV, the multivariable models were sequentially adjusted for current ART regimen, timing of ART initiation and CD4 nadir. Random effect of the caregiver was included in all models to account for nesting of children within households. Time was entered as a class variable to model potentially non-linear patterns. A time by early ART exposure interaction was included to assess the potentially changing effect of ART exposure over the course of 12 months. The least-square (LS) means according to the ART exposure were outputs from the LME models, and differences among them were tested at each time point. When there was no appreciable time trend, the LS means were averaged over time within the LME model, and differences by the main effect of ART exposure were tested. As cognitive outcomes are age- and sex-standardized, estimated SMD is comparable to Cohen’s effect size. |SMD| values ≥ 0.50 are universally recognized as being of clinical importance for patient-reported outcomes [43]. However, there is a precedent for judging |SMD| ≥ 0.33 as clinically important for the outcome of quality of life (QOL) or well-being – a patient-reported outcome similar to proxy reported cognition of dependent children in this study [44]. Like QOL, attainment of cognitive potential is of central lifelong importance for achieving the human potential of developing children. Therefore, | SMD| < 0.33, 0.33 ≤ |SMD| < 0.50 and |SMD| ≥ 0.50 are considered to be of small, moderate and large clinical importance, respectively, in this study according to existing precedent for QOL. [44] All hypotheses tests were two-sided at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

A total of 201 HIV-affected children were enrolled and followed for 12 months. During the in utero or peripartum period, most (n = 102, 50.7%) had no ART exposure, 20.9% (n = 42) were exposed to sdNVP ± ZDV, 10.9% (n = 22) were exposed to sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC and 17.4% (n = 35) were exposed to cART. Most caregiver and child demographic, clinical and HIV-treatment related factors (if CPHIV) were similar for children with and without IPA exposure. However, CHEU with IPA exposure were more likely than CHEU peers without IPA exposure, to have a female caregiver (98.1% vs. 86.6%) and a caregiver in the highest quintile of functioning (27.3% vs. 11.1%). Likewise, a greater proportion of CPHIV with IPA relative to no IPA exposure had biological parent caregivers (88.6% vs. 64.9%), and higher ASI score [mean (SD): 0.34 (1.0) vs. ‒0.24 (0.77)] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic description of adult caregivers and clinical description of perinatally exposed or infected children of HIV-infected women from Uganda from birth to 6–10 years of age. Data are n (%) unless noted otherwise

| CHEU (n = 100) |

CPHIV (n = 101) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In utero/peripartum ART-exposed (n = 55) |

No in utero/peripartum ART exposure (n = 45) |

P-value† |

In utero/peripartum ART-exposed (n = 44) |

No in utero/peripartum ART exposure (n = 57) |

P-value† | |

| Caregiver sociodemographics | ||||||

| Female sex | 54 (98.1) | 39 (86.6) | 0.025 | 38 (90.5) | 51 (91.1) | 0.920 |

| Biological parent | 52 (94.6) | 40 (88.9) | 0.300 | 39 (88.6) | 37 (64.9) | 0.006 |

| Caregiver depressed | 26 (48.2) | 17 (37.8) | 0.300 | 12 (28.6) | 10 (17.9) | 0.208 |

| Has own income | 40 (74.1) | 32 (71.1) | 0.742 | 31 (75.6) | 39 (70.9) | 0.608 |

| Caregiver age (years) [mean (SD)] | 35.3 (7.8) | 36.6 (8.4) | 0.432 | 32.2 (6.2) | 35.5 (9.9) | 0.062 |

| Highest caregiver quality (5th quintile) | 15 (27.3) | 5 (11.1) | 0.044 | 11 (25.0) | 9 (15.7) | 0.249 |

| Child demographic/clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Female child | 32 (59.3) | 22 (40.7) | 0.354 | 21 (43.8) | 27 (56.3) | 0.971 |

| Child current age (years) [mean (SD)] | 7.5 (1.4) | 7.5 (1.4) | 0.775 | 7.8 (1.6) | 7.9 (1.4) | 0.570 |

| Height for age z-score [mean (SD)] | 0.54 (1.3) | 0.41 (1.17) | 0.921 | −0.05 (1.1) | −0.06 (1.19) | 0.944 |

| 5-min Apgar score [mean (SD)] | 8.0 (2.0) | 7.4 (2.9) | 0.186 | 7.9 (2.4) | 7.9 (1.8) | 0.951 |

| Birth weight (kg) [mean (SD)] | 3.53 (0.76) | 3.43 (0.50) | 0.480 | 3.36 (0.53) | 3.27 (0.48) | 0.415 |

| Caregiver-reported cognitive score * [mean (SD)] | ||||||

| Adaptive Skills Index (ASI) | 0.05 (1.04) | 0.06 (0.98) | 0.961 | 0.34 (1.0) | −0.24 (0.77) | 0.002 |

| Behavioural symptoms index (BSI) | 0.16 (1.01) | −0.08 (1.02) | 0.246 | −0.06 (1.03) | −0.05 (0.86) | 0.940 |

| Internalizing problems composite (IPC)) | 0.18 (0.97) | −0.09 (1.05) | 0.191 | 0.07 (1.04) | −0.03 (0.91) | 0.606 |

| Externalizing problems composite (EPC) | 0.23 (1.07) | −0.05 (1.09) | 0.191 | 0.03 (1.02) | −0.10 (0.87) | 0.491 |

| Global executive composite (GEC) | 0.07 (1.13) | −0.12 (1.04) | 0.395 | −0.23 (0.91) | 0.04 (0.94) | 0.146 |

| cART treatment-related factors (if HIV-positive) | ||||||

| Current child cART status/regimen | ||||||

| NNRTI regimen (nevirapine/efavirenz) | – | – | – | 25 (56.8) | 38 (71.7) | 0.222 |

| Protease inhibitor (lopinavir/ritonivir/kaletra) | – | – | – | 18 (40.9) | 13 (24.5) | |

| cART-naïve | – | – | – | 1 (2.3) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Currently virologically suppressed | – | – | – | 22 (64.7) | 30 (58.8) | 0.586 |

| Child ever had AIDS-defining condition | – | – | – | 8 (18.8) | 10 (19.2) | 0.896 |

| CD4 measures | – | – | – | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| CD4 nadir (cells/μL) | – | – | – | 799.6 (505) | 766 (606) | 0.773 |

| Current CD4 (cells/μL) | – | – | – | 1316 (635) | 1236 (676) | 0.556 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; cART, combination ART; CPHIV, children perinatally HIV-infected; CHEU, children HIV-exposed but uninfected; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; –, not applicable.

ASI includes child proficiency in the following five areas: adaptability, social skills, leadership, activities of daily living and functional communication; BSI captures extent of the child having the following problematic behaviours: attention problems, atypicality, withdrawal, depression, hyperactivity, aggression; IPC includes display of behaviours consistent with depression, anxiety, somatization; EPC captures children’s display of the following problematic behaviours: hyperactivity, aggression, conduct problems; GEC is a global measure of caregiver rating of a dependent child for behaviours reflective of deficits in executive function – it integrates all eight executive function subscales (inhibition, shift, emotional control, initiation, working memory, planning organization, materials organization and monitoring).

P-value for difference in proportion (via χ2 tests) or difference in means (via t-tests) for children with and without any in utero/peripartum ART exposure.

IPA-related difference in SEA 6–10 years later among CHEU

Among CHEU, a consistent trend of worse performance in all cognitive outcomes by 6–10 years old was evident for sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC vs. no IPA exposure. Adjusted for caregiver demographic factors, sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC vs. no IPA predicted a moderate decline in ASI (SMD = ‒0.36, 95% CI: ‒0.75–0.02), a moderate to large increase in BSI, IPC and EPC domains of SEA (SMD = 0.63–0.76, 95% CI: 0.00–1.44) and a large increase in executive dysfunction (SMD = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.30–1.31). With further adjustment for caregiving quality and caregiver depression, sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC vs. no IPA-associated cognitive deficit was attenuated and of small (ASI: SMD = ‒0.30, 95% CI: ‒0.67–0.08) to moderate clinical importance for BSI, IPC and EPC domains of SEA (SMD = 0.40–0.52, 95% CI: ‒0.17–1.19) and for global executive dysfunction (SMD = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.06–1.03). However, IPA exposures including cART or peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV vs. no IPA exposure were not related to cognitive performance and associations were of small clinical importance (i.e. |SMD| < 0.28) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Early life antiretroviral therapy (ART) exposure as a determinant of socioemotional adjustment and executive function over a 12-month period in 6- to 10-year-old perinatally HIV-exposed, uninfected Ugandan children with or without maternal ART

| Unadjusted comparisons |

Multivariable model 1 |

Multivariable model 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | LSM ± SE | SMD (95% CI) | LSM ± SE | SMD (95% CI) | LSM ± SE | SMD (95% CI) | |

| (a) Adaptive Skills Index † | |||||||

| Early ART | |||||||

| None | 45 | 0.13 ± 0.11 | Ref. | 0.06 ± 0.09 | Ref. | 0.11 ± 0.11 | Ref. |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 18 | 0.48 ± 0.25 | 0.35 (−0.20–0.90) | 0.44 ± 0.24 | 0.38 (−0.20–0.95) | 0.35 ± 0.23 | 0.23 (−0.29–0.75) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 12 | −0.20 ± 0.13 | −0.34 (−0.69–0.02) | −0.29 ± 0.15 | −0.36 (−0.75–0.02) | −0.18 ± 0.16 | −0.30 (−0.67–0.08) |

| cART | 25 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.18 (−0.16–0.51) | 0.24 ± 0.13 | 0.18 (−0.17–0.48) | 0.23 ± 0.13 | 0.11 (−0.21–0.43) |

| (b) Behavioural symptoms index † | |||||||

| Early ART | |||||||

| None | 45 | −0.11 ± 0.12 | Ref. | −0.11 ± 0.12 | Ref. | −0.22 ± 0.11 | Ref. |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 18 | −0.39 ± 0.16 | −0.29 (−0.71–0.13) | −0.27 ± 0.16 | −0.17 (−0.56–0.22) | −0.09 ± 0.17 | 0.07 (−0.40–0.55) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 12 | 0.63 ± 0.31 | 0.73 (0.04–1.41) | 0.66 ± 0.27 | 0.76 (0.08–1.44) | 0.29 ± 0.28 | 0.52 (−0.16–1.19) |

| cART | 25 | −0.05 ± 0.15 | 0.05 (−0.38–0.48) | −0.09 ± 0.19 | 0.01 (−0.45–0.48) | −0.17 ± 0.17 | 0.06 (−0.44–0.38) |

| (c) Internalizing problems composite † | |||||||

| Early ART | |||||||

| None | 45 | −0.10 ± 0.13 | Ref | −0.08 ± 0.11 | Ref | −0.19 ± 0.10 | Ref |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 18 | −0.29 ± 0.15 | −0.19 (−0.59–0.20) | −0.15 ± 0.15 | −0.07 (−0.44–0.31) | 0.00 ± 0.16 | 0.19 (−0.19–0.56) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 12 | 0.53 ± 0.29 | 0.63 (−0.01–1.27) | 0.55 ± 0.26 | 0.63 (0.00–1.27) | 0.22 ± 0.27 | 0.40 (−0.12–0.96) |

| cART | 25 | −0.00 ± 0.16 | 0.10 (−0.33–0.52) | −0.03 ± 0.19 | 0.06 (−0.40–0.51) | −0.10 ± 0.18 | 0.08 (−0.39–0.43) |

| (d) Externalizing problems composite † | |||||||

| Early ART | |||||||

| None | 45 | −0.02 ± 0.15 | Ref | 0.01 ± 0.13 | Ref | −0.10 ± 0.12 | Ref |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 18 | −0.17 ± 0.15 | −0.15 (−0.55–0.26) | −0.05 ± 0.17 | 0.07 (−0.49–0.35) | 0.12 ± 0.19 | 0.22 (−0.23–0.66) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 12 | 0.59 ± 0.30 | 0.61 (−0.07–1.29) | 0.69 ± 0.25 | 0.68 (0.06–1.30) | 0.35 ± 0.26 | 0.45 (−0.17–1.07) |

| cART | 25 | 0.08 ± 0.17 | 0.10 (−0.36–0.55) | 0.08 ± 0.20 | 0.07 (−0.41–0.55) | 0.02 ± 0.17 | 0.11 (−0.31–0.54) |

| (e) Global executive composite deficits † | |||||||

| Early ART | |||||||

| None | 45 | 0.06 ± 0.14 | Ref | −0.01 ± 0.12 | Ref | −0.13 ± 0.11 | Ref |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 18 | −0.32 ± 0.22 | −0.38 (−0.90–0.14) | −0.39 ± 0.23 | −0.37 (−0.91–0.16) | −0.18 ± 0.19 | −0.05 (−0.51–0.41) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 12 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | 0.81 (0.39–1.23) | 0.79 ± 0.20 | 0.80 (0.30–1.31) | 0.41 ± 0.19 | 0.54 (0.06–1.03) |

| cART | 25 | −0.25 ± 0.20 | −0.31 (−0.81–0.19) | −0.38 ± 0.23 | −0.33 (−0.87–0.20) | −0.42 ± 0.22 | −0.28 (−0.79–0.23) |

3TC, lamivudine; cART, combination ART; sdNVP, single-dose nevirapine; ZDV, zidovudine.

Estimates shown are time-averaged peripartum ART regimen vs. no peripartum ART-related standardized mean difference (SMD) in respective socioemotional adjustment outcomes. Least-square means (LSMs) and corresponding standard errors (SEs) are also shown from corresponding models. SMD values reflect clinically meaningful change in age/sex-standardized outcomes interpreted according to the Cohen criteria as follows: small to modest, ES < |0.33|; moderate, |0.33| ≤ ES < |0.50|; strong/large, ES ≥ |0.50|. Bolded figures represent statistically significant values with 95% confidence at α = 0.05 level.

All estimates are calculated from repeated-measures linear mixed models adjusted for time, ART regimen and ART regimen × time. Multivariable model 1 is adjusted for caregiver demographic factors (age, sex, education, parent vs. non-parent relationship with child). Multivariable Model 2 is adjusted for all variables in model 1 plus caregiving quality and caregiver depression.

Early ART Regimen × time OR simply ART Regimen x time, P > 0.10.

IPA-related SEA and EF dysfunction 6–110 years later among CPHIV

Among CPHIV, peripartum cART (SMD = ‒0.82, 95% CI: ‒1.37 to ‒0.28) and intrapartum sdNVP ± ZDV (SMD = ‒0.41, 95% CI: ‒0.81 to ‒0.00) vs. no IPA predicted moderate to large reductions in executive dysfunction 6–10 years later. For all other SEA outcomes, CPHIV with cART or sdNVP ± ZDV IPA vs. peers without IPA exposure had comparable cognitive outcomes 6–10 years later, even after adjusting for caregiving context and HIV-specific factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Early life antiretroviral therapy (ART) exposure in relationship to time-averaged performance in socioemotional adjustment outcomes over a 12-month period in 6- to 10-year-old perinatally HIV-infected Ugandan children with or without maternal ART

| Unadjusted comparison |

Multivariable model 1 |

Multivariable model 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | LSM ± SE | SMD (95% CI) | LSM ± SE | SMD (95% CI) | LSM ± SE | SMD (95% CI) | |

| (a) Behavioural symptoms index † | |||||||

| Early ART* | |||||||

| None | 57 | −0.13 ± 0.10 | Ref. | −0.12 ± 0.12 | Ref. | −0.12 ± 0.12 | Ref. |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 24 | −0.30 ± 0.20 | −0.17 (−0.71–0.36) | −0.20 ± 0.20 | −0.05 (−0.57–0.47) | −0.22 ± 0.23 | −0.10 (−0.69–0.50) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 10 | −0.04 ± 0.21 | 0.09 (−0.49–0.67) | −0.23 ± 0.23 | −0.08 (−0.64–0.48) | −0.08 ± 0.21 | 0.05 (−0.53–0.62) |

| cART | 10 | −0.29 ± 0.15 | −0.16 (−0.61–0.28) | −0.52 ± 0.20 | −0.38 (−0.91–0.16) | −0.53 ± 0.22 | −0.41 (−1.08–0.27) |

| (b) Internalizing problems composite † | |||||||

| Early ART* | |||||||

| None | 57 | −0.08 ± 0.09 | Ref. | −0.08 ± 0.09 | Ref. | −0.02 ± 0.11 | Ref. |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 24 | −0.19 ± 0.20 | −0.11 (−0.65–0.43) | −0.16 ± 0.18 | −0.07 (−0.55–0.40) | −0.13 ± 0.21 | −0.11 (−0.66–0.44) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 10 | 0.12 ± .24 | 0.20 (−0.43–0.84) | −0.14 ± 0.21 | −0.06 (−0.58–0.46) | 0.05 ± 0.19 | 0.07 (−0.44–0.57) |

| cART | 10 | −0.10 ± 0.15 | −0.02 (−0.45–0.41) | −0.35 ± 0.17 | −0.27 (−0.75–0.21) | −0.33 ± 0.18 | −0.31 (−0.91–0.29) |

| (c) Externalizing problems composite † | |||||||

| Early ART* | |||||||

| None | 57 | ‒0.07 ± 0.10 | Ref. | −0.11 ± 0.12 | Ref. | −0.15 ± 0.12 | Ref. |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 24 | −0.22 ± 0.17 | −0.15 (−0.63–0.34) | −0.13 ± 0.19 | −0.02 (−0.50–0.45) | −0.21 ± 0.22 | −0.06 (−0.63–0.51) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 10 | 0.12 ± 0.21 | 0.19 (−0.37–0.75) | 0.00 ± 0.24 | 0.11 (−0.45–0.67) | 0.05 ± 0.22 | 0.20 (−0.42–0.82) |

| cART | 10 | −0.20 ± 0.17 | −0.13 (−0.60–0.35) | −0.36 ± 0.17 | −0.25 (−0.75–0.24) | −0.40 ± 0.18 | −0.25 (−0.84–0.35) |

| d) Global executive composite deficits † | |||||||

| Early ART* | |||||||

| None | 57 | 0.05 ± 0.10 | Ref. | 0.04 ± 0.10 | Ref. | 0.08 ± 0.11 | Ref. |

| sdNVP/sdNVP + ZDV | 24 | −0.33 ± 0.12 | −0.38 (−0.76–0.01) | −0.36 ± 0.13 | −0.40 (−0.79 to −0.01) | −0.33 ± 0.25 | −0.40 (−0.81 to −0.00) |

| sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC | 10 | 0.49 ± 0.24 | 0.44 (−0.20–1.09) | 0.38 ± 0.28 | 0.34 (−0.33–1.01) | 0.37 ± 0.25 | 0.29 (−0.35–0.92) |

| cART | 10 | −0.54 ± 0.20 | −0.59 (−1.03 to −0.04) | −0.75 ± 0.20 | −0.79 (−1.32 to −0.26) | −0.74 ± 0.20 | 0.82 (−1.37 to −0.28) |

3TC, lamivudine; cART, combination ART; sdNVP, single-dose nevirapine; ZDV, zidovudine.

Estimates shown are time-averaged peripartum ART regimen vs. no peripartum ART-related standardized mean difference (SMD) in respective socioemotional adjustment outcomes. Least square means and corresponding standard errors are also shown from corresponding models. SMD values reflect clinically meaningful change in age/sex standardized outcomes interpreted as: small, SMD < |0.33|; moderate, |0.33| ≤ SMD < |0.50|; and strong/large, SMD ≥ |0.50|. Bolded figures represent statistically significant values with 95% confidence at α = 0.05 level.

All estimates are calculated from repeated-measures linear mixed models adjusted for time, ART regimen, ART regimen × time. Multivariable model 1 is adjusted for caregiver factors (age, sex, education, parent vs. non-parent status, caregiving quality and caregiver depression). Multivariable model 2 is adjusted for all variables in model 1 plus current HIV management-related factors and CD4 nadir.

Early ART Regimen × time OR simply ART Regimen xtime, P > 0.10.

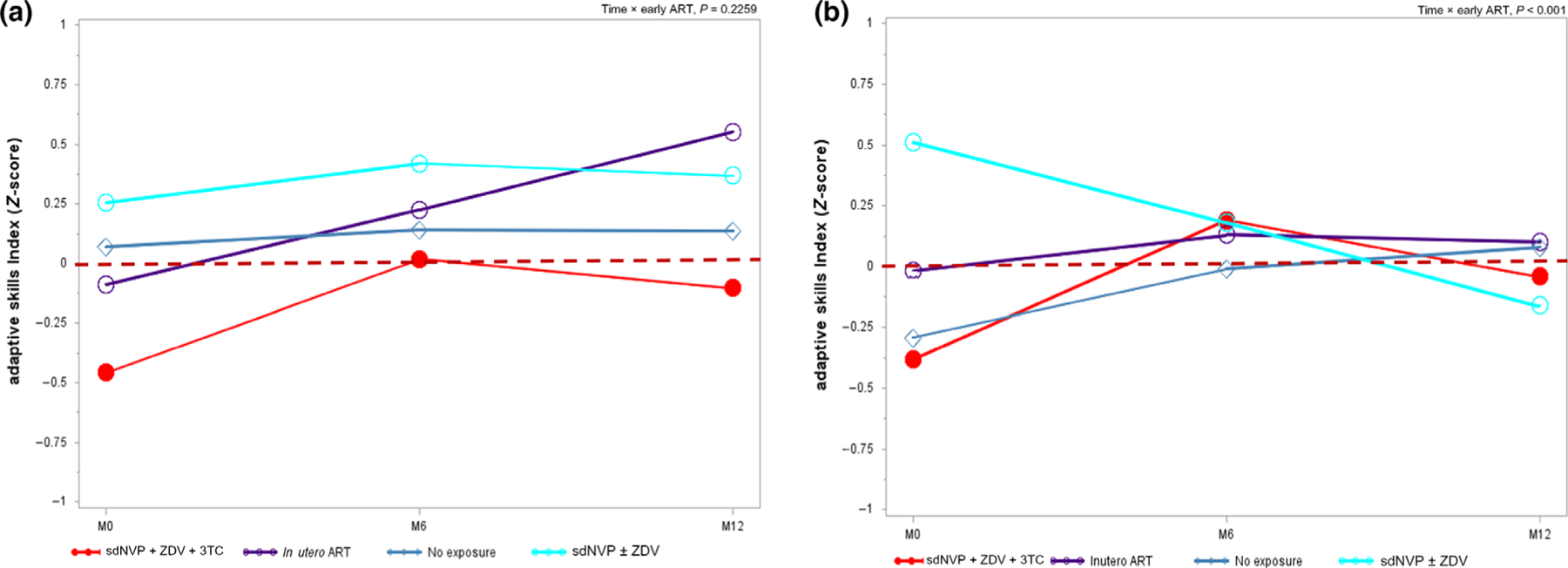

IPA relationship to SEA varied over a 12-month period for ASI, but not for global EF

Among HIV-exposed children followed from 6 to 10 years old, IPA-related 12-month change in ASI was stable among CHEU (time × early ART, P = 0.22) but not among CPHIV (time × early ART, P < 0.01; Fig. 1). Among CPHIV, sdNVP ± ZDV vs. no IPA exposure associated ASI advantage present at enrolment (SMD = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.21,1.39) attenuated substantially to an advantage of small clinical importance by month 6 (SMD = 0.19, 95% CI: ‒0.34–0.72). Further, by study month 12 sdNVP ± ZDV vs. no IPA exposure was associated with ASI disadvantage of small clinical importance (SMD = ‒0.25, 95% CI: ‒0.73–0.27) (Fig. 1). Although the relative magnitude of specific IPA vs. no IPA-related change in global executive dysfunction varied by HIV status, the direction was consistent over 12 months regardless of HIV status (time × early ART, P ≥ 0.502). Regardless of HIV status, peripartum sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC was associated with greater executive dysfunction 6–10 years later, whereas peripartum cART predicted lower executive dysfunction over the same 6–10-year period in comparison to peers without IPA exposure (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Peripartum antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen-related trend in adaptive skills index (ASI) over 1 year among 6–10 years old children from Uganda perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (a) and perinatally HIV-infected (b).sdNVP ± ZDV, single-dose nevirapine ± zidovudine; M0/6/12, month 0/6/12. Data are age- and sex-standardized. Source: PHAPS2-CIPHER. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Fig. 2.

Peripartum antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen-related trend in global executive dysfunction over 1 year among 6–10 years old children from Uganda perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (a) and perinatally HIV-infected (b). sdNVP ± ZDV, single-dose nevirapine ± zidovudine; M0/6/12, month 0/6/12. Data are age- and sex-standardized. Source: PHAPS2-CIPHER. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discussion

In this cohort of HIV-exposed Ugandan children born between 2008 and 2012, most received no IPA intervention for PMTCT of HIV. It is notable that the proportion of HIV-positive women who received ART for PMTCT in Uganda increased from 9% in 2004 to 33% by end of 2007 [45]. When IPA intervention occurred, maternal exposure was dependent of being CD4-eligible and, when applicable, varied in type and duration according to year of pregnancy [33]. For their infant, it often included intrapartum administration of sdNVP ± ZDV ± 3TC to newborns within 72 h of delivery and continued for 1 week. A small number of children born to pregnant women on ART for their own health had the benefit of optimal intervention (cART). These low IPA exposure rates and the low prevalence of optimal IPA regimen are a direct reflection of the prevailing standard of HIV care in the study locale during the era of the children’s birth because HIV-positive pregnant women had to meet minimum immune suppression thresholds to be provided with cART [45]. Independent of caregiver factors – age, sex, socioeconomic circumstances, depression, quality of caregiving, psychosocial stress and child’s current ART regimen (if CPHIV) – early life IPA-regimen related differences in neurodevelopmental trajectory were evident by 6–10 years later. With few exceptions, many of the observed peripartum IPA-related differences in SEA and EF at baseline assessment were sustained over 12 months of follow-up. However, while the IPA regimen was associated with cognition, the direction of association and the specific domains affected varied according to perinatal HIV status. Overall, these findings are consistent with our a priori hypothesis that IPA exposure during critical developmental windows is associated with cognitive performance in the long term. Results underscore the need for investigations along the developmental life-course continuum, as associations may be dynamic within extended developmental windows [46].

In utero or peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV and relationship to cognition at 6–10 years of age

In CPHIV and CHEU alike, our data suggest that there is no association between prophylactic peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV exposure and behavioural dysfunction subscales of SEA 6–10 years later. Among CHEU, this exposure was also not associated with global EF competencies, while CPHIV demonstrated a different pattern of association for global executive function and adaptive subscales of SEA. Specifically, among CPHIV, an initial positive association of large clinical importance between peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV and ASI at enrolment was downgraded to small clinical importance 6 months later. By the study’s end, peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV was observed to have an adverse association with ASI of modest clinical importance among CPHIV. This unstable association of sdNVP ± ZDV with adaptive skills over 12 months beginning from age 6–10 years, if true, may suggest that sustaining the cognitive advantage of a beneficial exposure in the long term requires intentional efforts to optimize current biopsychosocial circumstances. Our team has recently reported on the importance of high-quality nutrition [47,48] and stress [49,50] in relationship to cognition in this sample. With respect to stress, we found that SEA, QOL and psychosocial adjustment of CPHIV are comparable to CHEU and HUU peers in Uganda among children of caregivers who reported low psychosocial stress. However, the same outcomes for CPHIV were substantially worse when the primary care-giver reported high levels of psychosocial adversity [49,50]. In other words, in highly vulnerable CPHIV, it is imperative to provide consistent and predictable social support and high-quality nutrition, and to minimize psychosocial adversity, if any neurodevelopmental benefits of potentially healthy peripartum exposures are to be maintained. However, it is also possible that fluctuations in IPA relationship to adaptive skills over the 12-month prospective observation period represent an inherent measurement error in the outcome determination driven by differences in how caregivers interpreted assessment questions about adaptive skills for their dependent children.

These absent or unclear relationships between prophylactic sdNVP ± ZDV exposure and SEA outcomes contrast with evidence of a sustained protective association of large clinical importance between sdNVP ± ZDV and EF 6–10 years later among CPHIV. On the one hand, the lack of any, or an inconsistent, association between SEA outcomes and peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV among CPHIV and CHEU is not surprising given that sdNVP ± ZDV is, with hindsight, a suboptimal intervention that may not have sufficiently normalized the in utero immune environment of HIV-exposed children. Our findings for CHEU are aligned with observations in the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trial Group at 3.2–5.6 years of age [51]. They are also consistent with previously reported similarity in cognition as assessed by the Mullen scale of early development for Zambian CHEU exposed to zidovudine vs. CHEU peers exposed to cART at 2 years old [15] and with similarity in cognitive and language outcomes for CHEU vs. HUU at 15–36 months old [13]. Our data suggest that this direction of association is sustained in later childhood years.

In utero or peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV + 3TC and relationship to cognition at 6–10 years of age

We show internally consistent evidence that behavioural and executive dysfunction was consistently higher in CHEU exposed to sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC vs. CHEU peers without IPA exposure. This finding is similar to reports of peripartum efavirenz + ZDV + 3TC exposure-associated higher risk of socioemotional and adverse developmental outcomes among CHEU from Malawi at 24 months [52] and to suggestive evidence of peripartum ZDV exposure-associated higher risk of hyperactivity by 3 years of age in a small sample of CHEU from Venezuela [53]. Studies have implicated NRTIs such as ZDV and 3TC in central nervous system neuronal mitochondrial toxicity [54], in particular mitochondrial dysfunction after IPA exposure in the third trimester [55]. Complementary evidence from studies of mice subjected to ZDV + 3TC combination treatment have demonstrated the greatest mitochondrial DNA damage [56], resulting in adverse somatic/sensorimotor development and adverse behavioural and social interaction relative to mice exposed to the same agents separately [57]. Therefore, exposure to a combined ZDV + 3TC regimen in a sensitive developmental window has plausible potential to induce the kinds of behavioural dysfunctions that impair the ability of CHEU to appropriately engage cognitive processes necessary to cope with social stress and to self-monitor in a variety of goal-oriented, social and academic contexts [58,59].

We note that this observation among CHEU contrasts with the absence of any evidence that peripartum sdNVP ± ZDV + 3TC vs. no IPA was associated with cognitive outcomes by 6–10 years of age among CPHIV. This discrepancy of association by perinatal HIV status may in part reflect the huge differences in physiological status between CHEU and CPHIV who require cART for life. The neurodevelopmental trajectory of these two groups of children may be fundamentally different and confounded by chronic HIV-related morbidity, which limits the ability to detect an association between cognition assessed at 6–10 years old and this more distal peripartum cART exposure.

In utero or peripartum cART and relationship to cognition at 6–10 years of age

In line with our study thesis, peripartum cART exposure predicted sustained gains of large clinical importance by the early school-age years among CPHIV. This finding is also internally consistent with a pattern of cART-related modest to moderate reductions in BSI, IPC and EPC domains of SEA in CPHIV. These cART-associated positive trends in executive function and multiple SEA subscales reflect the long-term cognitive sparing benefit of having an immunologically stable intrauterine environment with relatively lower viraemia that is directly linked to maternal cART in pregnancy [4]. This finding is similar to the neuroprotective association reported for certain cART regimens among American children aged 1–12 years in the SMARTT cohort [4]. However, future specifically designed investigations will be important to confirm and clarify the observed encouraging cART-related long-term cognitive benefit among CPHIV children.

Among CHEU, cognitive outcomes by 6–10 years of age were comparable for those with peripartum cART exposure and peers without any IPA exposure. Boivin et al. [60] recently reported no difference in cognition for CHEU with in utero cART exposure sustained through breastfeeding cessation as compared with similarly aged HUU children at 48 months. Yet another study found a lower frequency of adaptive behaviour with a higher frequency of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes for CHEU exposed to various IPA vs. HUU children [46]. While those investigations are similar in empirical intent to the present study, there are important differences that make direct comparison tenuous. Unlike Boivin et al. [60], for example, our study base is, by design, constrained to understanding the long-term neurodevelopmental trajectory of children born to HIV-infected women who differed by type and quality of IPA exposure in sensitive developmental windows. Future studies where HIV-exposed children with and without IPA exposures are compared against HUU children will be important to confirm whether cART-related cognitive sparing noted for CHEU in this study mitigates the disparity in cognitive outcome relative to HUU children.

Limitations and strengths

In this study, proxy-reported neurodevelopmental outcomes were used. Proxy-reported outcome measures are positively associated, though not equivalent to, children’s self-report of the same outcomes or performance-based measures of cognition. Further, in some IPA categories, the number of children were small (e.g. among CPHIV, 10 each received cART or 3TC-inclusive IPA), possibly limiting the statistical power in multivariable models. Additional limitations lie in the absence of randomization which precludes elimination of residual confounding by design and the fact that this analysis did not distinguish between timing of cART exposure in pregnancy. The latter means this study provides no insights about gestational timing of IPA and severity of long-term neurodevelopmental trajectory. In spite of these limitations, we have used longitudinal design with repeated assessment of cognitive endpoints, robust control for confounding covariates and ascertained IPA exposures from objective medical records, which limits primary exposure misclassification. These are important strengths that should increase confidence in our reported findings. Additional strength lies in our use of sensitive cognitive competencies, such as executive function and SEA, that emerge progressively through early childhood and late adolescence [61,62] via complex interaction between children and their environments [63]. This study therefore provides insights into children’s functional adjustment to their respective environmental contexts and has implications for devising strategies to optimize learning and scholastic achievement [64], impulse control, chronic disease self-management and other adaptive skills for social success [65]. Lastly, in light of the small sample size of exposed children within certain IPA strata, e.g. cART, standardized mean differences or effect size rather than risk differences were calculated as a measure of effect to provide much-needed information on the clinical importance of respective associations. Larger future studies will be important to confirm these findings.

In summary, among children exposed to HIV and various ART regimens during the peripartum period, we demonstrate that no IPA regimens have equal long-term cognitive effects. [66] Among CPHIV, cART and sdNVP ± ZDV IPA exposure predicted, on average, lower executive dysfunction 6–10 years later. However, peripartum sdNVP + ZDV + 3TC predicted executive and SEA dysfunction among CHEU 6–10 years later. These data underscore the need for longitudinal studies across the developmental continuum to understand ART-related long-term cognitive sequelae in HIV-affected children. Given the high burden of cognitive impairment in this population, empirically informed strategies to identify at-risk CHEU for remedial interventions are needed to support long-term functional survival among the growing global population of CHEU.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge with thanks the kind indulgence of study participants and the diligence of our field research staff, Nakigudde Gorreth, Esther Nakayenga, Faridah Nakatya, Irene Asiingura, Arnold Katta and Phiona Nalubowa.

Funding: Research support for data collection was provided by the International AIDS Society (grant no. 327-EZE, CIPHER).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available only upon request and subject to terms of a data use and collaboration agreement.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2018 2018.

- 2.McCormack SA, Best BM. Protecting the fetus against HIV infection: a systematic review of placental transfer of antiretrovirals. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014; 53 (11): 989–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Traore H, Meda N, Nagot N et al. Determinants of low birth weight among newborns to HIV-infected mothers not eligible for antiretroviral treatment in Africa. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2013; 61 (5): 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams PL, Hazra R, Van Dyke RB et al. Antiretroviral exposure during pregnancy and adverse outcomes in HIV-exposed uninfected infants and children using a trigger-based design. AIDS 2016; 30 (1): 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez S, Catalan-Garcia M, Moren C et al. Placental mitochondrial toxicity, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and adverse perinatal outcomes in HIV pregnancies under antiretroviral treatment containing zidovudine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 75 (4): e113–e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jao J, Powis KM, Kirmse B et al. Lower mitochondrial DNA and altered mitochondrial fuel metabolism in HIV-exposed uninfected infants in Cameroon. AIDS 2017; 31 (18): 2475–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noguera-Julian A, Moren C, Rovira N et al. Decreased mitochondrial function among healthy infants exposed to antiretrovirals during gestation, delivery and the neonatal period. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34 (12): 1349–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poirier MC, Gibbons AT, Rugeles MT, Andre-Schmutz I, Blanche S. Fetal consequences of maternal antiretroviral nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor use in human and nonhuman primate pregnancy. Curr Opin Pediatr 2015; 27 (2): 233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill AJ, Kovacsics CE, Vance PJ, Collman RG, Kolson DL. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 deficiency and associated glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity is a highly conserved HIV phenotype of chronic macrophage infection that is resistant to antiretroviral therapy. J Virol 2015; 89 (20): 10656–10667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Underwood J, Robertson KR, Winston A. Could antiretroviral neurotoxicity play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in treated HIV disease? AIDS 2015; 29 (3): 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens J, Lyall H. Mother to child transmission of HIV: what works and how much is enough? J Infect 2014; 69 (Suppl 1): S56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coelho AV, Tricarico PM, Celsi F, Crovella S. Antiretroviral treatment in HIV-1-positive mothers: neurological implications in virus-free children. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18 (2): 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngoma MS, Hunter JA, Harper JA et al. Cognitive and language outcomes in HIV-uninfected infants exposed to combined antiretroviral therapy in utero and through extended breast-feeding. AIDS 2014; 28 (Suppl 3): S323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debeaudrap P, Bodeau-Livinec F, Pasquier E et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in HIV-infected and uninfected African children. AIDS 2018; 32 (18): 2749–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaudhury S, Mayondi GK, Williams PL et al. In-utero exposure to antiretrovirals and neurodevelopment among HIV-exposed-uninfected children in Botswana. AIDS 2018; 32 (9): 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chi BH, Stringer JSA, Moodley D. Antiretroviral drug regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a review of scientific, program, and policy advances for sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2013; 10 (2): 124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHenry MS, McAteer CI, Oyungu E et al. Neurodevelopment in young children born to HIV-infected mothers: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2018; 141 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice ML, Buchanan AL, Siberry GK et al. Language impairment in children perinatally infected with HIV compared to children who were HIV-exposed and uninfected. J Develop Behav Pediat 2012; 33 (2): 112–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozyce ML, Huo Y, Williams PL et al. Safety of in utero and neonatal antiretroviral exposure: cognitive and academic outcomes in HIV-exposed, uninfected children 5–13 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33 (11): 1128–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puthanakit T, Ananworanich J, Vonthanak S et al. Cognitive function and neurodevelopmental outcomes in HIV-infected children older than 1 year of age randomized to early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy: the PREDICT neurodevelopmental study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32 (5): 501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuke R, Sikorskii A, Zalwango SK et al. Psychosocial adjustment in Ugandan children: coping with human immunodeficiency virus exposure, lifetime adversity, and importance of social support. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2020; 2020 (171): 55–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiStefano C, Greer FW, Dowdy E. Examining the BASC-3 BESS parent form-preschool using rasch methodology. Assessment 2019; 26 (6): 1162–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gioia G, Isquith P, Guy S, Kenworthy L. BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Lutz, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ezeamama AE, Guwatudde D, Wang M et al. High perceived social standing is associated with better health in HIV-infected Ugandan adults on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Behav Med 2016; 39 (3): 453–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamer RM. Compute six intraclass correlation measures 2000; http://support.sas.com/kb/25/031.html. Accessed August 3, 2015.

- 26.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86 (2): 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson JB, Musoke P, Fleming T et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: 18-month follow-up of the HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet 2003; 362 (9387): 859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cressey TR, Jourdain G, Lallemant MJ et al. Persistence of nevirapine exposure during the postpartum period after intrapartum single-dose nevirapine in addition to zidovudine prophylaxis for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 38 (3): 283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mmiro FA, Aizire J, Mwatha AK et al. Predictors of early and late mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a breastfeeding population: HIV Network for Prevention Trials 012 experience, Kampala. Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52 (1): 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palumbo P, Lindsey JC, Hughes MD et al. Antiretroviral treatment for children with peripartum nevirapine exposure. N Engl J Med 2010; 363 (16): 1510–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudgens MG, Taha TE, Omer SB et al. Pooled individual data analysis of 5 randomized trials of infant nevirapine prophylaxis to prevent breast-milk HIV-1 transmission. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56 (1): 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fillekes Q, Kendall L, Kitaka S et al. Pharmacokinetics of zidovudine dosed twice daily according to World Health Organization weight bands in Ugandan HIV-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33 (5): 495–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Antitretroviral treatment and care guidelines for adults, adolescents and children Kampala, Uganda, The Director General Health Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Appendix II. Youth risk behavior surveillance system questionnaire. Public Health Rep 1993; 108 (Suppl 1): 60–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barkin JL, McKeever A, Lian B, Wisniewski SR. Correlates of postpartum maternal functioning in a low-income obstetric population. J Am Psychiat Nurses 2017; 23 (2): 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glover DA, Garcia-Aracena EF, Lester P, Rice E, Rothram-Borus MJ. Stress Biomarkers as outcomes for HIV plus prevention: participation, feasibility and findings among HIV plus Latina and African American Mothers. Aids Behav 2010; 14 (2): 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tibshirani R Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso: a retrospective. J R Stat Soc B 2011; 73: 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155 (2): 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones HE, Schooling CM. Let’s Require the “T-Word”. Am J Public Health 2018; 108 (5): 624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pazzagli L, Stuart EA, Hernan M, Schneeweiss S. Causal inference in pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidem Dr S 2019; 28: 414–415. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glass TA, Goodman SN, Hernan MA, Samet JM. Causal inference in public health. Annu Rev Publ Health 2013; 34: 61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernan MA. Beyond exchangeability: The other conditions for causal inference in medical research. Stat Methods Med Res 2012; 21 (1): 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 2003; 41 (5): 582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erder MH, Santanello N, Hays RD. Assessing the clinical significance of patient-reported outcomes: examples drawn from a recent meeting of the drug information association (DIA). Clin Ther 2003; 25: D12–D13. [Google Scholar]

- 45.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2008 2008. Available at https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/jc1510_2008globalreport_en_0.pdf.

- 46.Smith ML, Puka K, Sehra R, Read SE, Bitnun A. Longitudinal development of cognitive, visuomotor and adaptive behavior skills in HIV uninfected children, aged 3–5 years of age, exposed pre- and perinatally to anti-retroviral medications. AIDS Care 2017; 29 (10): 1302–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yakah W, Fenton JI, Sikorskii A et al. Serum Vitamin D is differentially associated with socioemotional adjustment in early school-aged Ugandan children according to perinatal HIV status and In utero/peripartum antiretroviral exposure history. Nutrients 2019; 11 (7): 1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jain R, Ezeamama AE, Sikorskii A et al. Serum n-6 Fatty Acids are Positively Associated with Growth in 6-to-10-Year Old Ugandan Children Regardless of HIV Status-A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2019; 11 (6): 1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ezeamama AE, Zalwango SK, Tuke R et al. Toxic Stress and Quality of Life in Early School-Aged Ugandan Children With and Without Perinatal Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2020; 2020 (171): 15–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuke R, Sikorskii A, Zalwango SK et al. Psychosocial Adjustment in Ugandan Children: Coping With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Exposure, Lifetime Adversity, and Importance of Social Support. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2020; 2020 (171): 55–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Culnane M, Fowler M, Lee SS et al. Lack of long-term effects of in utero exposure to zidovudine among uninfected children born to HIV-infected women. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 219/076 Teams. JAMA 1999; 281 (2): 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassidy AR, Williams PL, Leidner J et al. In Utero Efavirenz Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in HIV-exposed Uninfected Children in Botswana. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019; 38 (8): 828–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carneiro M, Sanchez A, Maneiro P, Angelosante W, Perez C, Vallee M. Vertical HIV-1 transmission: prophylaxis and paediatric follow-up. Placenta 2001;22 Suppl A:S13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Apostolova N, Blas-Garcia A, Esplugues JV. Mitochondrial interference by anti-HIV drugs: mechanisms beyond Polgamma inhibition. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2011; 32 (12): 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brogly SB, Ylitalo N, Mofenson LM et al. In utero nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor exposure and signs of possible mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-uninfected children. AIDS 2007; 21 (8): 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan SS, Santos JH, Meyer JN et al. Mitochondrial toxicity in hearts of CD-1 mice following perinatal exposure to AZT, 3TC, or AZT/3TC in combination. Environ Mol Mutagen 2007; 48 (3–4): 190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venerosi A, Valanzano A, Alleva E, Calamandrei G. Prenatal exposure to anti-HIV drugs: neurobehavioral effects of zidovudine (AZT) + lamivudine (3TC) treatment in mice. Teratology 2001; 63 (1): 26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brittain K, Myer L, Phillips N et al. Behavioural health risks during early adolescence among perinatally HIV-infected South African adolescents and same-age, HIV-uninfected peers. AIDS Care 2019; 31 (1): 131–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piske M, Budd MA, Qiu AQ et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes and in-utero antiretroviral exposure in HIV-exposed uninfected children. Aids 2018; 32 (17): 2583–2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Webster KD, de Bruyn MM, Zalwango SK et al. Caregiver socioemotional health as a determinant of child well-being in school-aged and adolescent Ugandan children with and without perinatal HIV exposure. Trop Med Int Health 2019; 24 (5): 608–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carlson SM. Social origins of executive function development. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 2009; 2009 (123): 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper RP. Development of executive function: more than conscious reflection. Dev Sci 2009; 12 (1): pp. 19–20; discussion 24–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beauchamp MH, Anderson V. SOCIAL: An integrative framework for the development of social skills. Psychol Bull 2010; 136 (1): 39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richland LE, Burchinal MR. Early executive function predicts reasoning development. Psychol Sci 2013; 24 (1): 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopes PN, Nezlek JB, Extremera N et al. Emotion Regulation and the Quality of Social Interaction: Does the Ability to Evaluate Emotional Situations and Identify Effective Responses Matter? J Pers 2011; 79 (2): 429–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robertson FC, Holmes MJ, Cotton MF et al. Perinatal HIV Infection or Exposure Is Associated With Low N-Acetylaspartate and Glutamate in Basal Ganglia at Age 9 but Not 7 Years. Front Hum Neurosci 2018; 12: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available only upon request and subject to terms of a data use and collaboration agreement.