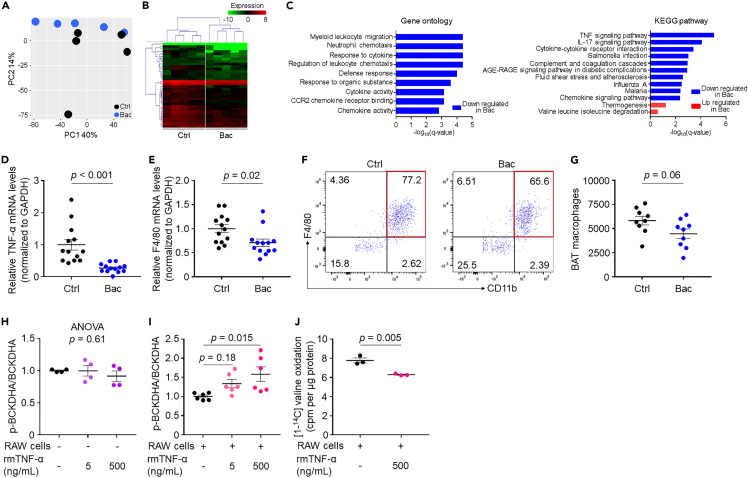

Figure 6.

Bacteroides treatment suppresses inflammation, which plays a key role in BAT BCAA catabolism

(A–C) BAT was collected at 18 weeks of age for RNA sequencing. n = 5 per group. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) score plots.

(B) Heat maps of cluster analysis showing the expression of differentially expressed genes in BAT of the indicated groups, with a dendrogram showing the clustering of genes and samples.

(C) Top terms showing enrichment based on −log10 (q-value) from gene ontology enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses.

(D and E) Real-time PCR of BAT TNF-α (D) and F4/80 (E) mRNA levels.

(F) Analysis of macrophages in BAT by flow cytometry. Red square indicates CD11b+F4/80+ cells among the CD45+Ly6G− population.

(G) Number of macrophages (CD45+Ly6G−CD11b+F4/80+) in BAT.

(H and I) The p-BCKDHA:BCKDHA ratio in HB2 cells stimulated with or without rmTNF-α (H) and co-cultured with RAW cells (I).

(J) Valine oxidation in HB2 cells co-cultured with RAW cells and stimulated with or without rmTNF-α. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM; two-tailed unpaired Student's t test (D, E, G, J); one-way ANOVA (H) followed by Tukey's post-hoc test (I). BCKDHA; branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase subunit E1α; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; p-BCKDHA, phospho-BCKDHA; rmTNF-α, recombinant murine tumor necrosis factor alpha.